Shahnameh by Firdausi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read the Report

2 0 0 5 a n n u a l r e p o r t You must be“ the change you wish to see in the world. ” — Gandhi Be the change. HEROES, NOT VICTIMS OUR MISSION HOW WE WORK Mercy Corps exists to alleviate suffering, poverty In our 25 years of experience, Mercy Corps has n a year of unprecedented disasters, the amazing and oppression by helping people build secure, learned that communities recovering from war or productive and just communities. social upheaval must be the agents of their own resilience of people the world over has been a triumph we transformation for change to endure. Making can all celebrate. Although millions of people are caught OUR CORE VALUES this happen requires communities, government I ■ We believe in the intrinsic value and dignity and businesses to solve problems in a spirit of in intolerable situations, in the midst of it all, they find the of human life. accountability and full participation. Ultimately, courage to survive, overcome and rebuild. ■ We are awed by human resilience, and believe in secure, productive and just communities arise only the ability of all people to thrive, not just exist. when all three sectors work together as three legs of a For every image of destruction and despair, there are stable stool. ■ Our spiritual and humanitarian values thousands of stories of inspiration. In this year’s report, compel us to act. WHAT WE DO we give voice to some of these remarkable individuals, from ■ We believe that all people have the right to ■ Emergency Relief live in peaceful communities and participate Indonesians recovering from the Indian Ocean tsunami to ■ Economic Development fully in the decisions that affect their lives. -

History of the Clan Macfarlane

HISTORY OF THE CLAN MACFARLAN Mrs. C. M. Little [gc M. L 929.2 M164t GENEALOGY COLLECTION I I 1149534 \ ALLEN CCnjmVPUBUCUBBABY, 334Z 3 1833 00859 Hf/^. I /^^^^^^ IIISTOKV OF TH1-: CLAN MACFARLANE, (.Macfai'lane) MACFARLAN. MACFARLAND, MACFARLIN. BY MRS. C. M. TJTTLE. TOTTENVILLE, N. Y. MRS. C. M. LITTLK. 1893. Copyrighted. Mrs. C. M. LITTLK 1893. For Private Circucation. 1149534 TO MY DEAR AND AGED MOTHER, WHO, IN HER NINETIETH YEAR, THE LAST OF HER GENERA- TION, WITH INTELLECT UNIMPAIRED, STANDS AS A WORTHY REPRESENTATIVE OF THE INDOM- ITABLE RACE OF MACFARLANE, THIS BOOK IS REVERENTLY deDicatgD, BY HER AFFECTIONATE DAUGHTER, THE AUTHOR. — INTRODUCTION. " Why dost thou build the hall? Son of the winged days! Thou lookest from thy tower to-day; yet a few years and the blast of the desert comes: it howls in thy empty court." Ossian. Being, myself, a direct descendant of the Clan MacFarlane, the old "Coat of Arms" hanging up- on the wall one of my earliest recollections, the oft-repeated story of the great bravery at Lang- side that gave them the crest, the many tradi- tions told by those who have long since passed away, left npon my mind an impression so indeli- ble, that, as years rolled on, and I had become an ardent student of Scottish history, I determined to know more of my ancestors than could be gathered from oral traditions. At length, in the summer of 1891, traveling for the second time in Europe, I was enabled to exe- cute a long-cherished plan of spending some time at Arrochar, at the head of Loch Long, in the Highlandsof Scotland, the hereditary posses- sions for six hundred years of the chiefs of the Clan MacFarlane. -

Black Hawk, the Most Famous Grandson of Justin Morgan

The grandson of Justin Morgan was one of the most prolific sires in the history of the breed. His influence is seminal. By Brenda L. Tippin lack Hawk, the most famous grandson of Justin Morgan, had to get to him on their own four feet. Several strong remaining was described in Volume I of the Morgan Register as sirelines today trace through Black Hawk and for those few who Bfollows: “He comes nearer to our beau ideal of a perfect do not, his blood is repeatedly woven in through the dams. It is driving horse than any other animal we have ever seen. Possessed safe to say there is not a Morgan alive today who does not carry of abundance of spirit and life, there is also manifest a quietness multiple crosses to Black Hawk and a measurable percentage of and evenness of temper that make him under all circumstances his blood, as many of the surviving sirelines carry at least 6 to 7 perfectly controllable; his step is nervous and elastic, but no percent or more. Black Hawk very nearly started his own breed, unnecessary steps are taken. His style of movement is bold and commanding a stud fee of $100 when most of his contemporaries fearless, while every motion is instinct with grace.” Black Hawk was were only getting $2 or $3, and has more influence on Morgans said to be more like Justin Morgan than any of his sons. During of today in all disciplines than any other single Morgan in history the last 12 years of his life alone he was bred to 1,772 mares, with besides Justin Morgan himself. -

Town of Ossian, Indiana Code of Ordinances

TOWN OF OSSIAN, INDIANA CODE OF ORDINANCES 2020 S-4 Supplement contains: Local legislation current through Ord. 20-3-1, passed 3-9-2020 and State legislation current through 2020 Advance Legislative Service #2 Published by: AMERICAN LEGAL PUBLISHING CORPORATION 525 Vine Street Suite 310 Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 1-800-445-5588 www.amlegal.com AN ORDINANCE ENACTING AND ADOPTING A SUPPLEMENT TO THE CODE OF ORDINANCES FOR THE TOWN OF OSSIAN AND DECLARING AN EMERGENCY WHEREAS, American Legal Publishing Corporation of Cincinnati, Ohio, has completed the first supplement to the Code of Ordinances of the Town of Ossian, which supplement contains all ordinances of a general and permanent nature enacted since the original Code of Ordinances of the Town of Ossian; and WHEREAS, American Legal Publishing Corporation has recommended the revision or addition of certain sections of the Code of Ordinances which are based on or make reference to sections of the Indiana Code; and WHEREAS it is the intent of the Ossian Town Council to accept these updated sections in accordance with the changes of the law of the State of Indiana; and WHEREAS, it is necessary to provide for the usual daily operation of the municipality and for the immediate preservation of the public peace, health, safety and general welfare of the municipality that this ordinance take effect at an early date; NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT ORDAINED BY THE OSSIAN TOWN COUNCIL OF THE POLITICAL SUBDIVISION OF TOWN OF OSSIAN: Section 1. That the first supplement to the Code of Ordinances of the Town of Ossian as submitted by American Legal Publishing Corporation of Cincinnati, Ohio, as attached hereto, be and the same is hereby adopted by reference as if set out in its entirety. -

M. Iu. Lermontov

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 409 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Walter N. Vickery M. Iu. Lermontov His Life and Work Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access 00056058 SLAVISTICHE BEITRÄGE Herausgegeben von Peter Rehder Beirat: Tilman Berger • Walter Breu • Johanna Renate Döring-Smimov Walter Koschmal ■ Ulrich Schweier • Milos Sedmidubsky • Klaus Steinke BAND 409 V erla g O t t o S a g n er M ü n c h en 2001 Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access 00056058 Walter N. Vickery M. Iu. Lermontov: His Life and Work V er la g O t t o S a g n er M ü n c h en 2001 Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access PVA 2001. 5804 ISBN 3-87690-813-2 © Peter D. Vickery, Richmond, Maine 2001 Verlag Otto Sagner Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner D-80328 München Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier Bayerisch* Staatsbibliothek Müocfcta Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access When my father died in 1995, he left behind the first draft of a manuscript on the great Russian poet and novelist, Mikhail Lermontov. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

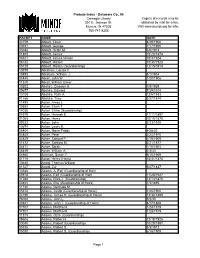

Probate Index - Delaware Co., in Carnegie Library Copies of Records May Be 301 E

Probate Index - Delaware Co., IN Carnegie Library Copies of records may be 301 E. Jackson St. obtained by mail for a fee. Muncie, IN 47305 Visit www.munpl.org for info. 765-747-8208 PACKET NAME DATE 04759 Abbott, Elmer 8/29/1908 03931 Abbott, George 1/17/1900 05684 Abbott, Hettie M. 5/6/1913 01805 Abbott, James 10/20/1874 08521 Abbott, James Vinson 10/3/1924 08132 Abbott, Marion 10/30/1923 05729 Abbott, Marion (Guardianship) 12/15/1914 10979 Abraham, Louisa C. 10495 Abraham, William J. 8/1/1934 04445 Abrell, John W. 1/20/1906 11510 Abrell, William Elmer 10202 Abshire, Dawson A. 3/8/1929 05677 Abshire, Edward 7/29/1914 10109 Abshire, Ruth A. 12/6/1933 01165 Abshire, Tirey 3/27/1874 11495 Acker, Amos L. 10852 Acker, Elijah T. 14038 Acker, Elvira (Guardianship) 04578 Acker, Hannah E. 11/11/1897 01065 Acker, Henry 10/15/1870 09322 Acker, John 2/23/1926 13674 Acker, Lewis H. 06404 Acker, Maria Priddy 4/28/33 04845 Acker, Peter 3/24/1910 04829 Acker, Samuel P. 3/19/1909 01672 Acker, Sanford M. 2/21/1877 04471 Acker, Sarah 1/10/1905 06459 Acker, William A. 2/3/33 04960 Ackman, Susan F. 9/10/1909 01716 Ackor, Henry (Heirs) 10/31/1870 13648 Acord, Thomas Willard 01527 Acord, Zur 9/27/1837 13546 Adams, A. Earl (Guardianship of Heir) 05918 Adams, Earl (Guardianship of Heir) 11/28/1927 01288 Adams, Eliza J. (Guardianship) 12/13/1870 03465 Adams, Ella (Guardianship of Heirs) 7/5/1895 11740 Adams, Gertrude M. -

Britishness and Problems of Authenticity in Post-Union Literature from Addison to Macpherson

"Where are the originals?" Britishness and problems of authenticity in post-Union literature from Addison to Macpherson. Melvin Eugene Kersey III Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Leeds, School of English September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the generous help, encouragement and support of many people. My research has benefited beyond reckoning from the supervision of Professor David Fairer, whose inspired scholarship has never interfered with his commitment to my research. It is difficult to know whether to thank or to curse Professor Andrew Wawn for introducing me to James Macpherson's Ossianic poetry during my MA at Leeds, but at any rate I am now doubly indebted to him for his insightful reading of a chapter of this thesis. I am also grateful to Professor Paul Hammond for his enormously helpful comments and suggestions on another chapter. And despite the necessary professional distance which an internal examiner must maintain, I have still enjoyed the benevolent proximity effect of Professor Edward Larrissy. I am grateful to Sue Baker and the administrative staff of the School of English for providing me with employment and moral support during this thesis, especially Pamela Rhodes. Special thanks to the inestimable help, friendship and rigorous mind of Dr. Michael Brown, and to Professor Terence and Sue Brown for their repeated generous hospitality in Dublin. -

An Intensive Historical Site Survey of the Washington Prairie Settlement

A INTENSIVE HISTORICAL SITE SURVEY OF THE WASHINGTON PRAIRIE SETTLEMENT i By the Winneshiek Historic Preservation Commission Courthouse Decorah, Iowa 52101 July 10, 1990 By Steven L. Johnson, principal investigator, Rev. Donald Berg, historian, and Charles Langton, photographer. This project has been funded with the assistance of a matching grant-in-aid (i.e., Contract No. 19-89-40045A.007) from the State of Iowa, Bureau of Historic Preservation, through the Department of the Interior, National Park Service, under the provisions of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966; the opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of the Department of the Interior. Acknowledgements This survey is a cooperative effort by the Iowa Bureau of Historic Preservation, the Winneshiek County Board of Supervisors (CLG), Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum, and Winneshiek County Historical Society. A special thank you goes to Lowell Soike, historian for the state preservation office; Rev. Donald Berg, historian for the project; Wayne Wangsness, David and Elaine Hegg, members of the Washington Prairie Church Historical Committee; Rev. Richard Sansgaard, minister at the Washington Prairie Lutheran Church; Charles Langton, project photographer. The Norwegian-American Museum deserves a thank-you for giving staff time to assist with the project. The survey crew would like to express its appreciation to the members of the Washington Prairie area for their time and work in completing this project. Table of Contents I. Abstract II. Introduction A. List of Si tes B. Map of Sites C. Elisabeth Koren's 1850s Map III. Survey Research Design A. Survey Objective B. Description of Area Surveyed C. -

Lyra Celtica : an Anthology of Representative Celtic Poetry

m^ 0^. 3)0T gaaggg^g'g'g^g'g'g^^^gg'^^^ gggjggggg^g^^gsgg^gggs ^^ oooooooo ^^ — THE COLLECTED WORKS OF "FIONA MACLEOD" (WILLIAM SHARP) I. Pharais ; The Mountain Lovers. II. The Sin-Eater ; The Washer of the Ford, Etc. III. The Dominion of Dreams ; Under the Dark Star. IV. The Divine Adventure ; lona ; Studies in Spiritual History. V. The Winged Destiny ; Studies in the Spiritual History of the Gael. VI. The Silence of Amor; Where the Forest Murmurs. VII. Poems and Dramas. The Immortal Hour In paper covers. SELECTED WRITINGS OF WILLIAM SHARP I. Poems. II. Studies and Appreciations. III. Papers, Critical and Reminiscent. IV. Literary, Geography, and Travel Sketches. V. Vistas : The Gipsy Christ and other Prose Imaginings. Uniform with above, in two volumes A MEMOIR OF WILLIAM SHARP (FIONA MACLEOD) Compiled by Mrs William Sharp LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN "The Celtic Library LYRA CELTICA First Edition ..... 1896 Second Edition (ReHsed and EnloTged) . 1924 LYRA CELTICA AN ANTHOLOGY OF REPRE- SENTATIVE CELTIC POETRY EDITED BY E. A. SHARP AND J. MATTHAY WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES By WILLIAM SHARP ANCIENT IRISH, ALBAN, GAELIC, BRETON, CYMRIC, AND MODERN SCOTTISH AND IRISH CELTIC POETRY EDINBURGH: JOHN GRANT 31 GEORGE IV. BRIDGE 1924 4 Ap^ :oT\^ PRINTED IN ORgAT BRITAIH BY OLIVER AND BOTD BDINBUROH CONTENTS a troubled EdeHy rich In throb of heart GEORGE MEREDITH CONTENTS PAGB INTRODUCTION .... xvii ANCIENT IRISH AND SCOTTISH The Mystery of Amergin The Song of Fionn .... Credhe's Lament .... Cuchullin in his Chariot . Deirdrc's Lament for the Sons of Usnach The Lament of Queen Maev The March of the Faerie Host . -

2018 KWPN-NA Handbook.Indd

Table of Contents KWPN-NA Past and Future............................................ 2 Horses .................................................................................26 EVA Protocol for Stallions ...........................................50 GENERAL INFORMATION Immunizations, Shoes, Horse Attire,Artifi cial Means, OC Protocol for Stallion Approvals In N.A. ...........51 Drugs, Safety, Injury/Veterinary Disclosure, Whips. 2018 Stallion Roster ........................................................ 4 Time Frame for the Approval Process ....................51 Register A Horses and Foreign Mares ....................27 Boards and Committee Members ............................. 6 VETERINARY PROTOCOLS OC Protocol for Mare Selections chart ...................27 KWPN-NA Mission Statement .....................................7 PROK Radiograph Requirements/Protocol ...52-53 KEURING STANDARD .......................... 28-29 What‘s New for 2018 .......................................................7 NS/DJD Radiograph Requirements/Protocol ......54 2018 Stallion Service Auction ...................................42 LINEAR SCORING ................................... 30-31 Breathing Apparatus ....................................................55 2018 Fee Schedule ..................................................... 155 KEURING - INSPECTION GUIDELINES Reproductive System/Semen ....................................55 Common Questions ...................................................154 Premium Grading ..........................................................32 -

Poem S, Chiefly Scottish

POEM S, CHIEFLY SCOTTISH NOTES CRITICAL AND HISTORICAL ADDED. TO THE HEADER. BEFORE perusal of these wonderful Poems, chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, it may be of importance to the general reader to have some authoritative rule for pronouncing the language. The following directions by the Author himself, although usually reserved for an Appendix, are therefore prefixed the one from the Kilmarnock, the other from the Edinburgh Edition : The terminations be thus the may known ; participle present, instead of ing, ends, in the Scotch Dialect, in an or in; in an, particularly, when the verb is composed of the participle present, and any of the tenses of the auxiliary, to be. The past time and participle past are usually made by shortening the ed into '. The ch and gh have always the guttural sound. The sound of the English diphthong oo, is commonly spelled ou. The French u, a sound which often occurs in the Scotch language, is marked oo, or ui. The a in genuine Scotch words, except when forming a diphthong, or followed by an e mute after a single consonant, sounds generally like the broad English a in watt. The Scotch diphthongs, ae always, and ea very often, sound like the French <? masculine. The Scotch diphthong ey sounds like the Latin ei. To these may be added the following other general rules : 1. That ea, ei, ie, diphthongs, = ee, English: 2. That ow, final, in words at least of one syllable, = ou, English : 3. That owe, or ow-e, in like situations, . = ow, English : 4. That ch, initial or final, is generally soft, = ch, English; otherwise, or in such syllables as och, ach, aueh, hard, = gh, German : 5.