Slavery and Emancipation In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boone's Lick Heritage, Vol. 11, No. 2

BOONE’S LICK HERITAGE The Missouri River from the bluffs above historic Rocheport Two Historic Views of the Missouri River 19th-century Voyage Up the River and 20th-century Memoir of a One-time Riverman VOL. 11 NO. 2 — SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2012 BOONSLICK HISTORICAL SOCIETY PERIODICAL EDITOR’S PAGE A River Runs Through It . Our theme in this issue of Boone’s Lick Heritage is As a youngster growing up in the St. Louis area during water, specifically streams and rivers. Waterways have the 1940s, I was part of a family that often vacationed in played a major role in the exploration and settlement of this the southeastern Missouri Ozarks, a region defined by its country by Europeans, many of whom were finding and fol- many springs and spring-fed streams. The Current River, lowing the earlier pathways and villages of Native Ameri- for example, was born of and is sustained by spring waters, cans. Starting with the 1804-06 Corps of Discovery journey the largest of which is Big Spring near Van Buren. Big by Lewis and Clark up the Missouri, “our river” played the Spring and the Current are Ozark waters that tug at my starring role in the exploration and western movement of soul, especially when I’m absent from their rugged wa- our young nation. And the Missouri’s northern tributary, the tershed. The region’s many springs and the waters of the Mississippi (as many of us like to think), drew Gen. Lewis Current, along with those of its southern artery, called the Cass and Henry Rowe Jacks Fork, and the nearby Schoolcraft north in 1821 Eleven Point, course and Schoolcraft again in through my veins and bind 1832, seeking its head- me to place as strongly as waters and source (Lake blood to family. -

Eliza Calvert Hall: Kentucky Author and Suffragist

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 2007 Eliza Calvert Hall: Kentucky Author and Suffragist Lynn E. Niedermeier Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Niedermeier, Lynn E., "Eliza Calvert Hall: Kentucky Author and Suffragist" (2007). Literature in English, North America. 54. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/54 Eliza Calvert Hall Eliza Calvert Hall Kentucky Author and Suffragist LYNN E. NIEDERMEIER THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Frontispiece: Eliza Calvert Hall, after the publication of A Book of Hand-Woven Coverlets. The Colonial Coverlet Guild of America adopted the work as its official book. (Courtesy DuPage County Historical Museum, Wheaton, 111.) Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2007 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Niedermeier, Lynn E., 1956- Eliza Calvert Hall : Kentucky author and suffragist / Lynn E. -

Slave Narratives and the Rhetoric of Author Portraiture Author(S): Lynn A

Slave Narratives and the Rhetoric of Author Portraiture Author(s): Lynn A. Casmier-Paz Source: New Literary History, Vol. 34, No. 1, Inquiries into Ethics and Narratives (Winter, 2003), pp. 91-116 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20057767 Accessed: 01/11/2010 18:04 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to New Literary History. http://www.jstor.org Slave Narratives and the Rhetoric of Author Portraiture Lynn A. -

Cutting Patterns in DW Griffith's Biographs

Cutting patterns in D.W. Griffith’s Biographs: An experimental statistical study Mike Baxter, 16 Lady Bay Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham, NG2 5BJ, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]) 1 Introduction A number of recent studies have examined statistical methods for investigating cutting patterns within films, for the purposes of comparing patterns across films and/or for summarising ‘average’ patterns in a body of films. The present paper investigates how different ideas that have been proposed might be combined to identify subsets of similarly constructed films (i.e. exhibiting comparable cutting structures) within a larger body. The ideas explored are illustrated using a sample of 62 D.W Griffith Biograph one-reelers from the years 1909–1913. Yuri Tsivian has suggested that ‘all films are different as far as their SL struc- tures; yet some are less different than others’. Barry Salt, with specific reference to the question of whether or not Griffith’s Biographs ‘have the same large scale variations in their shot lengths along the length of the film’ says the ‘answer to this is quite clearly, no’. This judgment is based on smooths of the data using seventh degree trendlines and the observation that these ‘are nearly all quite different one from another, and too varied to allow any grouping that could be matched against, say, genre’1. While the basis for Salt’s view is clear Tsivian’s apparently oppos- ing position that some films are ‘less different than others’ seems to me to be a reasonably incontestable sentiment. It depends on how much you are prepared to simplify structure by smoothing in order to effect comparisons. -

The Reeves Families of Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri and Iowa

THE REEVES FAMILIES OF VIRGINIA, KENTUCKY, MISSOURI AND IOWA by John M. Wanamaker 2001 Retyped in Microsoft Word by Michael L. Wilson, April 2017. I obtained a copy of this document from John M. Wanamaker in June 2002. It is presented as I got it, without trying to correct errors. The notes in brackets [] are by John. Further information can be found on my web site at: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~mlwilson/ THE REEVES FAMILIES OF VIRGINIA, KENTUCKY, MISSOURI AND IOWA. PREFACE Compiling this history has been quite an adventure. I began with a single sheet of paper – a mimeographed copy of a typewritten copy of the obituary of Benjamin H. Reeves. The paper was yellowed and the print was slanted down-hill from left to right and of poor quality. I do not know the origin of this paper. I only know it is something that I have “always had”. My next find, entirely by accident, was a plaque on a building in “Old Town” St. Charles, Mo. We had stopped to spend the night on a trip back from Pennsylvania in the summer of 1996. The dinner hour led us to explore the historic shop and restaurant district nearby. There on a shop front was a plaque that read; “Site of Eckert’s Tavern 1826 – 1846. In 1824 Congress authorized a trade road to Santa-Fe and appointed Geo. C. Sibley, Benj. Reeves and Thomas Mather to survey the route. Final reports of this survey were written here in the latter part of 1827.” Imagine my surprise! I then discovered the State Historical Society of Missouri and its “Western Historical Manuscript Collection”. -

Texts Checklist, the Making of African American Identity

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 A collection of primary resources—historical documents, literary texts, and works of art—thematically organized with notes and discussion questions I. FREEDOM pages ____ 1 Senegal & Guinea 12 –Narrative of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (Job ben Solomon) of Bondu, 1734, excerpts –Narrative of Abdul Rahman Ibrahima (“the Prince”), of Futa Jalon, 1828 ____ 2 Mali 4 –Narrative of Boyrereau Brinch (Jeffrey Brace) of Bow-woo, Niger River valley, 1810, excerpts ____ 3 Ghana 6 –Narrative of Broteer Furro (Venture Smith) of Dukandarra, 1798, excerpts ____ 4 Benin 11 –Narrative of Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua of Zoogoo, 1854, excerpts ____ 5 Nigeria 18 –Narrative of Olaudah Equiano of Essaka, Eboe, 1789, excerpts –Travel narrative of Robert Campbell to his “motherland,” 1859-1860, excerpts ____ 6 Capture 13 –Capture in west Africa: selections from the 18th-20th-century narratives of former slaves –Slave mutinies, early 1700s, account by slaveship captain William Snelgrave FREEDOM: Total Pages 64 II. ENSLAVEMENT pages ____ 1 An Enslaved Person’s Life 36 –Photographs of enslaved African Americans, 1847-1863 –Jacob Stroyer, narrative, 1885, excerpts –Narratives (WPA) of Jenny Proctor, W. L. Bost, and Mary Reynolds, 1936-1938 ____ 2 Sale 15 –New Orleans slave market, description in Solomon Northup narrative, 1853 –Slave auctions, descriptions in 19th-century narratives of former slaves, 1840s –On being sold: selections from the 20th-century WPA narratives of former slaves, 1936-1938 ____ 3 Plantation 29 –Green Hill plantation, Virginia: photographs, 1960s –McGee plantation, Mississippi: description, ca. 1844, in narrative of Louis Hughes, 1897 –Williams plantation, Louisiana: description, ca. -

Sarah G. Humphreys: Antebellum Belle to Equal Rights Activist, 1830-1907

SARAH G. HUMPHREYS: ANTEBELLUM BELLE TO EQUAL RIGHTS ACTIVIST, 1830-1907 MARY G. McBRIDE AND ANN M. MCLAURIN Although the biography of Sarah Thompson Gibson Hum- phreys seems to illustrate the development of a daughter of the planter class from antebellum belle to equal rights activist, by her own account Sarah was never intended by circumstances of heredity or education to be a conventional belle. Descended from a distinguished Southern family, Sarah was the daughter of Tobias Gibson of Mississippi and Louisiana Breckinridge Hart of Kentucky. In an undated autobiographical fragment written late in her life, Sarah described her mother, daughter of Na- thaniel Hart and Susan Preston of "Spring Hill," Woodford County, Kentucky, as a woman of "masculine intellect, great force of character and strength of will." Of Tobias Gibson, Sarah wrote: My father Tobias Gibson came of a long line of clergymen who were the pioneers of Methodism in the South. My father was a man of accurate education, of unusual culture and of broad ideas, far in advance of his time. Although by inheritance a large slave owner he was at heart opposed to slavery. He was also that anomaly amongst Southern men a "Woman Suffragist." He believed and taught me to believe that "taxation without representation" was as unjust to women as to men and he educated me up to the idea that our ad- vancing civilizaioff would sooner or later demand not only the political enfranchisement of women but their equal share in the control of the government. The family divided its time between its Louisiana sugar planta- tions and its l•ome in Lexington, Kentucky. -

Image Credits, the Making of African

THE MAKING OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY: VOL. I, 1500-1865 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 IMAGE CREDITS Items listed in chronological order within each repository. ALABAMA DEPT. of ARCHIVES AND HISTORY. Montgomery, Alabama. WEBSITE Reproduced by permission. —Physical and Political Map of the Southern Division of the United States, map, Boston: William C. Woodbridge, 1843; adapted to Woodbridges Geography, 1845; map database B-315, filename: se1845q.sid. Digital image courtesy of Alabama Maps, University of Alabama. ALLPORT LIBRARY AND MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS. State Library of Tasmania. Hobart, Tasmania (Australia). WEBSITE Reproduced by permission of the Tasmanian Archive & Heritage Office. —Mary Morton Allport, Comet of March 1843, Seen from Aldridge Lodge, V. D. Land [Tasmania], lithograph, ca. 1843. AUTAS001136168184. AMERICAN TEXTILE HISTORY MUSEUM. Lowell, Massachusetts. WEBSITE Reproduced by permission. —Wooden snap reel, 19th-century, unknown maker, color photograph. 1970.14.6. ARCHIVES OF ONTARIO. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. WEBSITE In the public domain; reproduced courtesy of Archives of Ontario. —Letter from S. Wickham in Oswego, NY, to D. B. Stevenson in Canada, 12 October 1850. —Park House, Colchester, South, Ontario, Canada, refuge for fugitive slaves, photograph ca. 1950. Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, F2076-16-6. —Voice of the Fugitive, front page image, masthead, 12 March 1854. F 2076-16-935. —Unidentified black family, tintype, n.d., possibly 1850s; Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, F 2076-16-4-8. ASBURY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY. Wilmore, Kentucky. Permission requests submitted. –“Slaves being sold at public auction,” illustration in Thomas Lewis Johnson, Twenty-Eight Years a Slave, or The Story of My Life in Three Continents, 1909, p. -

John W. Foster, Soldier and Politician by DANIELW

John W. Foster, Soldier and Politician By DANIELW. SNEPP Indiana’s sons have occupied a number of important gov- ernmental offices in Washington and diplomatic posts abroad. No Hoosier, however, has served his country longer or more faithfully than John Watson Foster. His public life spans a half century of diplomatic conflict in which the United States rose to the undisputed position of a world power. In the pres- ent generation, few, except students of diplomatic history and international law, have heard the name of John W. Foster or read his scholarly works on diplomacy and world peace. No published biography has yet recorded his achievements and no monument has been raised to perpetuate his memory. Nevertheless this obscure man was regarded by Ambassador James Bryce as “the most distinguished diplomat of our time,” and by Secretary of State Frelinghuysen as the most valuable man in foreign service in his day. Mr. Foster represented the United States upon more different missions of first rank than any other person, and was accordingly called by Chauncey M. DePew, “the handy-man of the State Department.” Andrew Johnson excepted, Foster served in one capacity or another under every president from Abraham Lincoln to Theodore Roosevelt. Diplomacy was to Foster not merely a calling, it was a profession. This article, however, is concerned only with that part of his life spent in Indiana. Foster’s English ancestry may be traced to the hardy tradespeople on his mother’s side and to the staunch yeoman class on his father’s side. The strain of the depression which followed on the heels of the Napoleonic Wars in England, fell most severely upon the middle class, great numbers of whom migrated to America. -

Madison County Freedom Trail (PDF)

N Hitchcock Point M Damon Point A I N Billington Bay 90 Lewis Point S Fisher Bay T N Dutchman Island JO O E Exit 34 R S S T T N AG H N P E I 13 L T R Briggs Bay Kawana Bay M L L D N A Wilson Point R D R R D D E R I Freedom Trail R H N Larkins Point Freedom Trail L D T S R K E U K E I D Messenger Bay S P B 5 N South Bay 1. Independent Church and Society of Canastota B R A D N K O Y 31 E R M V R H C A I D P U L E I L Oneida Valley A D L T N R AVE Canastota N S R E LITI K PO P DE S R Y R - Nelson United Methodist Church O Gifford Point T E D E D 2. William Anderson L RD V L N Y R S H Lakeport RBU R ATE A W W E ILSON D A AV E C V R R D T R E A H SMITH RID E T GE RD D S RD L R A O E I OR C 3. Francis Hawley E O R E M LENOX E L D E EL O N L V M S 8 W T RD Eaton Corners HITELAW O W R I A L S Gees Corners A P O LE D Whitelaw B WIS ST D I P H M N R I 4. -

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council © Essays compiled by Alicestyne Turley, Director Underground Railroad Research Institute University of Louisville, Department of Pan African Studies for the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, Frankfort, KY February 2010 Series Sponsors: Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Kentucky Historical Society Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council Underground Railroad Research Institute Kentucky State Parks Centre College Georgetown College Lincoln Memorial University University of Louisville Department of Pan African Studies Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) was established by executive order in 2004 to organize and coordinate the state's commemorative activities in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln. Its mission is to ensure that Lincoln's Kentucky story is an essential part of the national celebration, emphasizing Kentucky's contribution to his thoughts and ideals. The Commission also serves as coordinator of statewide efforts to convey Lincoln's Kentucky story and his legacy of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity for all. Kentucky African American Heritage Commission [Enabling legislation KRS. 171.800] It is the mission of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission to identify and promote awareness of significant African American history and influence upon the history and culture of Kentucky and to support and encourage the preservation of Kentucky African American heritage and historic sites. -

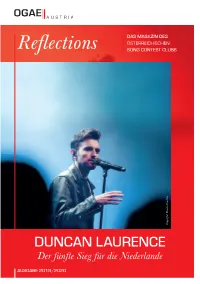

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected]