Biomechanics of Yoga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I on an Empty Stomach After Evacuating the Bladder and Bowels

• I on a Tllt' Bi11lr· ol' \lodt•nJ Yoga-It� Philo�opl1� and Prad il't' -hv thr: World" s Fon-·mo �l 'l'r·ar·lwr B • I< . S . IYENGAR \\ it h compldc· dt·!wription� and illustrations of all tlw po �tun·� and bn·athing techniqn··� With More than 600 Photographs Positioned Next to the Exercises "For the serious student of Hatha Yoga, this is as comprehensive a handbook as money can buy." -ATLANTA JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION "The publishers calls this 'the fullest, most practical, and most profusely illustrated book on Yoga ... in English'; it is just that." -CHOICE "This is the best book on Yoga. The introduction to Yoga philosophy alone is worth the price of the book. Anyone wishing to know the techniques of Yoga from a master should study this book." -AST RAL PROJECTION "600 pictures and an incredible amount of detailed descriptive text as well as philosophy .... Fully revised and photographs illustrating the exercises appear right next to the descriptions (in the earlier edition the photographs were appended). We highly recommend this book." -WELLNESS LIGHT ON YOGA § 50 Years of Publishing 1945-1995 Yoga Dipika B. K. S. IYENGAR Foreword by Yehudi Menuhin REVISED EDITION Schocken Books New 1:'0rk First published by Schocken Books 1966 Revised edition published by Schocken Books 1977 Paperback revised edition published by Schocken Books 1979 Copyright© 1966, 1968, 1976 by George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Patanjali Yogsutra & Mantras

THE LITTLE MASTER OF YOGA -2021 (Curriculum for TGMY Yoga) THE POSTURES Basic Level Advance Level (Day-3) (Day-1) (Day-2) 1. Siddhasana 16. Vrikshasana 1. Dhanurasana 11. Shirshana 2. Swastikasan 17. Mandukasana 2. Paschimottanasana 12. Rajkapotsana 3. Padmasana 18. Vrishasana 3. Sankatasana 13. Purn 4. Bhadrasana, 19. Shalabhasana 4. Mayurasana Matsyendrasana 5. Muktasana 20. Makarasana 5. Kukkutasana 14. Tittibhasana 6. Vajrasana 21. Ushtrasana 6. Kurmasana 15. Kaundinyasana 7. Svastikasana, 22. Bhujangasana 7. Uttanakurmakasana 16. Astavakrasana 23. Yogasana 8. Uttanamandukasan 8. Simhasana 17. Eka Pada Free Hand 9. Gomukhasana 24. Utkatasana 9. Garudasana Chakrasana 10. Virasana, 25. Savasana 10. Chakrasan 18. Purn 11. Mritasana Dhanurasana 12. Guptasana 19. Yoganidrasana 13. Matsyasana 20. Vrischikasana 14. Matsyendrasana 15. Gorakshana PATANJALI YOGSUTRA & MANTRAS Understanding of Yoga according to Text Mantras & Prayers - Definition of Yoga in - 5 general benefits of Yoga - Aum Chanting Patanjali - 5 general benefits of Asana - Aum Sahana Bhavtu - Definition of Yoga in Gita - 5 general benefits of - Gayatri Mantra - Definition of Yoga in Vedas Pranayama THE LITTLE MASTER OF YOGA The Little Master of Yoga contest is a great way to celebrate true sense of Yoga among the children for their individual practices, learning, and understanding with the philosophy of Yoga. The Little Master of Yoga contest for children of 9 to 17 years age group. Each phase of contest is taking the Little Masters towards various aspects of yoga and motivating them through proper understanding and its amazing benefits of Yoga. While preparing himself for this contest, the contestants are also advised to go through some other available resources also such as Yoga Literature, YouTube clips, newspaper articles, magazines, Yoga sites, and ancient texts. -

Venus Series-‐‑ Vegas

VENUS SERIES- VEGAS HOT Cat & Cow Pose: 1.Start on your hands and knees with your wrists directly under your shoulders, and your knees directly under your hips. Point your fingertips to the top of your mat. Place your shins and knees hip-width apart. Center your head in a neutral position and soften your gaze downward. 2. Begin by moving into Cow Pose: Inhale as you drop your belly towards the mat. Lift your chin and chest, and gaze up toward the ceiling. 3. Broaden across your shoulder blades and draw your shoulders away from your ears. 4.Next, move into Cat Pose: As you exhale, draw your belly to your spine and round your back toward the ceiling. The pose should look like a cat stretching its back. 5. Release the crown of your head toward the floor, but don't force your chin to your chest. 6. Inhale, coming back into Cow Pose, and then exhale as you return to Cat Pose. Pranayama Breathing: 1. Stand with your feet together. 2. Inhale deeply through your mouth. Feel the air of your inhalations passing down through your windpipe. 3. Now slightly contract the back of the throat, as you do when you whisper, and exhale. Imagine your breath is fogging up a window. 4. Keep this contraction of the throat as you inhale and exhale, then gently close your mouth and continue breathing through your nose. 5. Concentrate on the sound of the breath, which will soothe your mind. It should be audible to you, but not so loud that someone standing several feet away can hear it. -

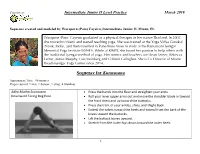

Sequence for Kurmasana

Courtesy of: Intermediate Junior II Level Practice March 2018 Sequence created and modeled by Waraporn (Pom) Cayeiro, Intermediate Junior II, Miami, FL Waraporn (Pom) Cayeiro graduated as a physical therapist in her native Thailand. In 2007, she moved to Miami and started teaching yoga. She was trained at the Yoga Vidya Gurukul (Nasik, India), and then travelled to Pune three times to study at the Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute (RIMYI). While at RIMYI, she found her passion to help others with the traditional Iyengar method of yoga. Her mentor and teachers are Dean Lerner, Rebecca Lerner, James Murphy, Lois Steinberg and Colleen Gallagher. She is Co-Director of Miami Beach Iyengar Yoga Center since 2014. Sequence for Kurmasana Approximate Time: 90 minutes Props required: 1 mat, 1 bolster, 1 strap, 4 blankets Adho Mukha Svanasana • Press the hands into the floor and straighten your arms. Downward Facing Dog Pose • Roll your inner upper arms out and move the shoulder blade in toward the front chest and up toward the buttocks. • Press the front of your ankles, shins, and thighs back. • Extend the calves toward the heels and extend from the back of the knees toward the buttocks. • Lift the buttock bones upward. • Stretch from the outer hips down toward the outer heels. 1 Padahastasana • From Uttanasana, place the hands under the feet. Hands to Feet Pose • Stretch both legs fully extended. • Spread the buttock bones and lengthen the spine. • Lengthen the armpits towards the elbows, and from the elbows to the hands. • Pull the hands up, while pressing the feet downward towards the floor. -

Thriving in Healthcare: How Pranayama, Asana, and Dyana Can Transform Your Practice

Thriving in Healthcare: How pranayama, asana, and dyana can transform your practice Melissa Lea-Foster Rietz, FNP-BC, BC-ADM, RYT-200 Presbyterian Medical Services Farmington, NM [email protected] Professional Disclosure I have no personal or professional affiliation with any of the resources listed in this presentation, and will receive no monetary gain or professional advancement from this lecture. Talk Objectives Provide a VERY brief history of yoga Define three aspects of wellness: mental, physical, and social. Define pranayama, asana, and dyana. Discuss the current evidence demonstrating the impact of pranayama, asana, and dyana on mental, physical, and social wellness. Learn and practice three techniques of pranayama, asana, and dyana that can be used in the clinic setting with patients. Resources to encourage participation from patients and to enhance your own practice. Yoga as Medicine It is estimated that 21 million adults in the United States practice yoga. In the past 15 years the number of practitioners, of all ages, has doubled. It is thought that this increase is related to broader access, a growing body of research on the affects of the practice, and our understanding that ancient practices may hold the key to healing modern chronic diseases. Yoga: A VERY Brief History Yoga originated 5,000 or more years ago with the Indus Civilization Sanskrit is the language used in most Yogic scriptures and it is believed that the principles of the practice were transmitted by word of mouth for generations. Georg Feuerstien divides the history of Yoga into four catagories: Vedic Yoga: connected to ritual life, focus the inner mind in order to transcend the limitations of the ordinary mind Preclassical Yoga: Yogic texts, Upanishads and the Bhagavad-Gita Classical Yoga: The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, the eight fold path Postclassical Yoga: Creation of Hatha (willful/forceful) Yoga, incorporation of the body into the practice Modern Yoga Swami (master) Vivekananda speaks at the Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. -

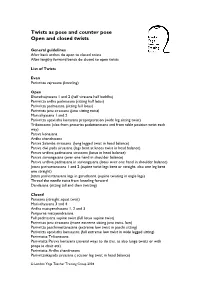

Twists As Pose & Counter Pose

Twists as pose and counter pose Open and closed twists General guidelines After back arches do open to closed twists After lengthy forward bends do closed to open twists List of Twists Even Parivritta vajrasana (kneeling) Open Bharadvajrasana 1 and 2 (half virasana half baddha) Parivritta ardha padmasana (sitting half lotus) Parivritta padmasana (sitting full lotus) Parivritta janu sirsasana (janu sitting twist) Marischyasana 1 and 2 Parivritta upavistha konasana prepreparation (wide leg sitting twist) Trikonasana (also from prasarita padottanasana and from table position twist each way) Parsva konasana Ardha chandrasana Parsva Salamba sirsasana (long legged twist in head balance) Parsva dwi pada sirsasana (legs bent at knees twist in head balance) Parsva urdhva padmasana sirsasana (lotus in head balance) Parsva sarvangasana (over one hand in shoulder balance) Parsva urdhva padmasana in sarvangasana (lotus over one hand in shoulder balance) Jatara parivartanasana 1 and 2 (supine twist legs bent or straight, also one leg bent one straight) Jatara parivartanasana legs in garudasana (supine twisting in eagle legs) Thread the needle twist from kneeling forward Dandasana (sitting tall and then twisting) Closed Pasasana (straight squat twist) Marischyasana 3 and 4 Ardha matsyendrasana 1, 2 and 3 Paripurna matsyendrasana Full padmasana supine twist (full lotus supine twist) Parivritta janu sirsasana (more extreme sitting janu twist, low) Parivritta paschimottanasana (extreme low twist in paschi sitting) Parivritta upavistha konsasana (full extreme -

INTERVIEW with B.K.S. IYENGAR on BACKBENDS 12/5/91 Questions Asked by Victor Oppenheimer and Patricia Walden

INTERVIEW WITH B.K.S. IYENGAR ON BACKBENDS 12/5/91 Questions asked by Victor Oppenheimer and Patricia Walden These questions were asked during the teachers’ backbend intensive Mr. Iyengar taught in November-December, 1991. This intensive was videotaped, and some of the questions refer to the videotapes. The interview was transcribed and edited by Francie Ricks. Victor Oppenheimer: Why backbends? B.K.S. Iyengar: In the asana systems, the most advanced postures are the backbends. The human structure is such that the idea does not strike anyone that the spinal vertebrae can be moved backward as well as forward and sideways, without causing injury. In the field of yoga, backbends are not taught at the early stages in the practice of this art, but only when the body is trained and when it is tuned and toned to such an extent that it can accept these poses. Backbends are to be felt more than expressed. The other postures can be expressed and then felt. But in backbends, like meditations, each person has to feel. And that’s why I thought that after fifty years of teaching, at least some of my students should get the background of the right means to perform the backbends. Backbends are not poses meant for exhibitionism. Backbends are meant to understand the back parts of our bodies. The front body can be seen with the eyes. The back body cannot be seen; it can only be felt. That’s why I say these are the most advanced postures, where the mind begins to look at the back, first on the peripheral level, then inwards, towards the core. -

An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health

WHOLE HEALTH: INFORMATION FOR VETERANS An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health Whole Health is an approach to health care that empowers and enables YOU to take charge of your health and well-being and live your life to the fullest. It starts with YOU. It is fueled by the power of knowing yourself and what will really work for you in your life. Once you have some ideas about this, your team can help you with the skills, support, and follow up you need to reach your goals. All resources provided in these handouts are reviewed by VHA clinicians and Veterans. No endorsement of any specific products is intended. Best wishes! https://www.va.gov/wholehealth/ An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health An Introduction to Yoga for Whole Health SUMMARY 1. One of the main goals of yoga is to help people find a more balanced and peaceful state of mind and body. 2. The goal of yoga therapy (also called therapeutic yoga) is to adapt yoga for people who may have a variety of health conditions or needs. 3. Yoga can help improve flexibility, strength, and balance. Research shows it may help with the following: o Decrease pain in osteoarthritis o Improve balance in the elderly o Control blood sugar in type 2 diabetes o Improve risk factors for heart disease, including blood pressure o Decrease fatigue in patients with cancer and cancer survivors o Decrease menopausal hot flashes o Lose weight (See the complete handout for references.) 4. Yoga is a mind-body activity that may help people to feel more calm and relaxed. -

Exercise Yogasan

EXERCISE YOGASAN YOGA The word meaning of “Yoga” is an intimate union of human soul with God. Yoga is an art and takes into purview the mind, the body and the soul of the man in its aim of reaching Divinity. The body must be purified and strengthened through Ashtanga Yogas-Yama, Niyama, Asanas and Pranayama. The mind must be cleansed from all gross through Prathyaharam, Dharana, Dhyanam and Samadhi. Thus, the soul should turn inwards if a man should become a yogic adept. Knowledge purifies the mind and surrender takes the soul towards God. TYPE OF ASANAS The asanas are poses mainly for health and strength. There are innumerable asanas, but not all of them are really necessary, I shall deal with only such asanas as are useful in curing ailments and maintaining good health. ARDHA CHAKRSANA (HALF WHEEL POSTURE) This posture resembles half wheel in final position, so it’s called Ardha Chakrasana or half wheel posture. TADASANA (PALM TREE POSE) In Sanskrit ‘Tada’ means palm tree. In the final position of this posture, the body is steady like a Palm tree, so this posture called as ‘Tadasana’. BHUJANGAASANA The final position of this posture emulates the action of cobra raising itself just prior to striking at its prey, so it’s called cobra posture or Bhujangasan. PADMASANA ‘Padma’ means lotus, the final position of this posture looks like lotus, so it is called Padmasana. It is an ancient asana in yoga and is widely used for meditation. DHANURASANA (BOW POSTURE) Dhanur means ‘bow’, in the final position of this posture the body resembles a bow, so this posture called Dhanurasana or Bow posture. -

Yoga Federation of India ( Regd

YOGA FEDERATION OF INDIA ( REGD. UNDER THE SOCIETIES REGISTRATION ACT. XXI OF 1860 REGD. NO.1195 DATED 14.02.90) RECOGNIZED BY INDIAN OLYMPIC ASSOCIATION - OCTOBER, 1998 TO FEBRUARY, 2011 Affiliated to Asian Yoga Federation, International Yoga Sports Federation & International Yoga Federation REGD. OFFICE: FLAT NO.501, GHS-93, SECTOR-20, PANCHKULA- 134116 (HARYANA), INDIA e-mail:[email protected], Mobile No.+91-94174-14741, Website:- www.yogafederationofindia.com SYLLABUS AND GUIDELINES FOR NATIONAL/ZONAL/STATE/DISTRICT YOGASANA COMPETITION SUB JUNIOR GROUP–A (8-1110 YEARS, BOYS & GIRLS) 1. VRIKSHASANA 2. PADAHASTASANA 3. SASANGASANA 4. USHTRASANA 5. AKARNA DHANURASANA 6. GARABHASANA 1. VRIKSHASANA 7. EKA PADA SIKANDHASANA 1. Back maximum stretched. 2. Arms touching the ear. 8. CHAKRASANA 3. Both hands folded above the 9. SARVANGASANA shoulders. 10. DHANURASANA 4. Gaze in front. 2. PADAHASTASANA 3. SASANGASANA 4. USHTRASANA 1. Hands on the side of feet 1. Thighs perpendicular to the ground 1. Thighs perpendicular to the ground 2. Legs should be straight 2. Forehead touching knees 2. Palms on the heels 3. Back maximum stretched 3. Palms on the heels from the side 3. Knees, heels and toes together 4. Chest & forehead touching the legs 4. Toes, heels and knees together 4. Ankles touching the ground 5. AKARNA DHANURASANA 6. GARABHASANA 7. EKA PADA SIKANDHASANA 1. One Leg stretch with toe pointing upwards, gripping of toe with thumb and 1. Both arms in between thigh and calf. 1. Back, neck and head to be maximum index finger. 2. Ears to be covered by palms. straight. 2. Gripping of toe of other leg with thumb, 2. -

Yoga Asana Pictures

! ! Padmasana – Lotus Pose Sukhasana – Easy Pose ! ! Ardha Padmasana – Half Lotus Pose Siddhasana – Sage or Accomplished Pose ! ! Vajrasana –Thunderbolt Pose Virasana – Hero Pose ! ! Supta Padangusthasana – Reclining Big Toe Pose Parsva supta padangusthasana – Side Reclining Big Toe Pose ! ! Parrivrtta supta padangusthasana – Twisting Reclining Big Toe Pose Jathara parivartanasana – Stomach Turning Pose ! ! Savasana – Corpse Pose Supta virasana – Reclining Hero Pose ! ! ! Tadasana – Mountain Pose Urdhva Hastasana – Upward Hands Pose Uttanasana – Intense Stretch or Standing Forward Fold ! ! Vanarasana – Lunge or Monkey Pose Adho mukha dandasana – Downward Facing Staff Pose ! ! Ashtanga namaskar – 8 Limbs Touching the Earth Chaturanga dandasana – Four Limb Staff Pose ! ! Bhujangasana – Cobra Pose Urdvha mukha svanasana – Upward Facing Dog Pose ! ! Adho mukha svanasana - Downward Facing Dog Pose Trikonasana – Triangle Pose ! ! Virabhadrasana II – Warrior II Pose Utthita parsvakonasana – Extended Lateral Angle (Side Flank) ! ! Parivrtta parsvakonasana – Twisting Extended Lateral Angle (Side Flank) Ardha chandrasana – Half Moon Pose ! ! ! Vrksasana – Tree Pose Virabhadrasana I – Warrior I Pose Virabhadrasana III – Warrior III Pose ! ! Prasarita Paddottasana – Expanded/Spread/Extended Foot Intense Stretch Pose Parsvottanasana – Side Intense Stretch Pose ! ! ! Utkatasana– Powerful/Fierce Pose or Chair Pose Uttitha hasta padangustasana – Extended Hand Big Toe Pose Natarajasana – Dancer’s Pose ! ! Parivrtta trikonasana- Twisting Triangle Pose Eka -

Ultimate Guide to Yoga for Healing

HEAD & NECK ULTIMATE GUIDE TO YOGA FOR HEALING Hands and Wrists Head and Neck Digestion Shoulders and Irritable Bowel Hips & Pelvis Back Pain Feet and Knee Pain Ankles Page #1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Click on any of the icons throughout this guide to jump to the associated section. Head and Neck .................................................Page 3 Shoulders ......................................................... Page 20 Hands and Wrists .......................................... Page 30 Digestion and IBS ......................................... Page 39 Hips ..................................................................... Page 48 Back Pain ........................................................ Page 58 Knees ................................................................. Page 66 Feet .................................................................... Page 76 Page #2 HEAD & NECK Resolving Neck Tension DOUG KELLER Pulling ourselves up by our “neckstraps” is an unconscious, painful habit. The solution is surprisingly simple. When we carry ourselves with the head thrust forward, we create neck pain, shoul- der tension, even disc herniation and lower back problems. A reliable cue to re- mind ourselves how to shift the head back into a more stress-free position would do wonders for resolving these problems, but first we have to know what we’re up against. When it comes to keeping our head in the right place, posturally speaking, the neck is at something of a disadvantage. There are a number of forces at work that can easily pull the neck into misalignment, but only a few forces that maintain the delicate alignment of the head on the spine, allowing all the supporting muscles to work in harmony. Page #3 HEAD & NECK The problem begins with the large muscles that converge at the back of the neck and attach to the base of the skull. These include the muscles of the spine as well as those running from the top of the breastbone along the sides of the neck (the sternocleidomastoids) to the base of the head.