Associated Motion with Deictic Directionals: a Comparative Overview Aicha Belkadi [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Workshop Proposal: Associated Motion in African Languages WOCAL 2021, Universiteit Leiden Organizers: Roland Kießling (Universi

Workshop proposal: Associated motion in African languages WOCAL 2021, Universiteit Leiden Organizers: Roland Kießling (University of Hamburg) Bastian Persohn (University of Hamburg) Daniel Ross (University of Illinois, UC Riverside) The grammatical category of associated motion (AM) is constituted by markers related to the verb that encode translational motion (e.g. Koch 1984; Guillaume 2016). (1–3) illustrate AM markers in African languages. (1) Kaonde (Bantu, Zambia; Wright 2007: 32) W-a-ká-leta buta. SUBJ3SG-PST-go_and-bring gun ʻHe went and brought the gun.ʻ (2) Wolof (Atlantic, Senegal and Gambia; Diouf 2003, cited by Voisin, in print) Dafa jàq moo tax mu seet-si la FOC.SUBJ3SG be_worried FOC.SUBJ3SG cause SUBJ3SG visit-come_and OBJ2SG ‘He's worried, that's why he came to see you.‘ (3) Datooga (Nilotic, Tanzania; Kießling, field notes) hàbíyóojìga gwá-jòon-ɛ̀ɛn ʃɛ́ɛróodá bàɲêega hyenas SUBJ3SG-sniff-while_coming smell.ASS meat ‘The hyenas come sniffing (after us) because of the meat’s smell.’ Associated motion markers are a common device in African languages, as evidenced in Belkadi’s (2016) ground-laying work, in Ross’s (in press) global sample as well as by the available surveys of Atlantic (Voisin, in press), Bantu (Guérois et al., in press), and Nilotic (Payne, in press). In descriptive works, AM markers are often referred to by other labels, such as movement grams, distal aspects, directional markers, or itive/ventive markers. Typologically, AM systems may vary with respect to the following parameters (e.g. Guillaume 2016): Complexity: How many dedicated AM markers do actually contrast? Moving argument:: Which is the moving entity (S/A vs. -

Verbs in Relation to Verb Complementation 11-69

1168 Complementation of verbs and adjectives Verbs in relation to verb complementation 11-69 They may be either copular (clause pattern SVC), or complex transitive verbs, or monotransitive verbs with a noun phrase object), we can give only (clause pattern SVOC): a sample of common verbs. In any case, it should be borne in mind that the list of verbs conforming to a given pattern is difficult to specífy exactly: there SVC: break even, plead guilty, Iie 101V are many differences between one variety of English and another in respect SVOC: cut N short, work N loose, rub N dry of individual verbs, and many cases of marginal acceptability. Sometimes the idiom contains additional elements, such as an infinitive (play hard to gel) or a preposition (ride roughshod over ...). Note The term 'valency' (or 'valencc') is sometimes used, instead of complementation, ror the way in (The 'N' aboye indicates a direct object in the case oftransitive examples.) which a verb determines the kinds and number of elements that can accompany it in the clause. Valency, however, incIudes the subject 01' the clause, which is excluded (unless extraposed) from (b) VERB-VERB COMBINATIONS complementation. In these idiomatic constructions (ef 3.49-51, 16.52), the second verb is nonfinite, and may be either an infinitive: Verbs in intransitive function 16.19 Where no eomplementation oecurs, the verb is said to have an INTRANSITIVE make do with, make (N) do, let (N) go, let (N) be use. Three types of verb may be mentioned in this category: or a participle, with or without a following preposition: (l) 'PURE' INTRANSITIVE VERas, which do not take an object at aH (or at put paid to, get rid oJ, have done with least do so only very rarely): leave N standing, send N paeking, knock N fiying, get going John has arrived. -

Conventions and Abbreviations

Conventions and abbreviations Example sentences consist of four lines. The first line uses a practical orthography. The second line shows the underlying morphemes. The third line is a gloss, and the fourth line provides a free translation in English. In glosses, proper names are represented by initials. Constituents are in square brackets. Examples are numbered separately for each chapter. If elements are marked in other ways (e.g. with boldface), this is indicated where relevant. A source reference is given for each example; the reference code consists of the initials of the speaker (or ‘Game’ for the Man and Tree games), the date the recording was made, and the number of the utterance. An overview of recordings plus reference codes can be found in Appendix I. The following abbreviations and symbols are used in glosses: 1 first person 2 second person 3 third person ADJ adjectiviser ANIM animate APPL applicative CAUS causative CLF classifier CNTF counterfactual COMP complementiser COND conditional CONT continuative DEF definiteness marker DEM demonstrative DIM diminutive DIST distal du dual EMP emphatic marker EXCL exclusive FREE free pronoun FOC focus marker HAB habitual IMP imperative INANIM inanimate INCL inclusive INT intermediate INTJ interjection INTF intensifier IPFV imperfective IRR irrealis MOD modal operator NEG negation marker NOM nominaliser NS non-singular PART partitive https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110675177-206 XXIV Conventions and abbreviations pc paucal PERT pertensive PFV perfective pl plural POSS possessive PRF perfect PROG progressive PROX proximate RECIP reciprocal REDUP reduplication REL relative clause marker sg singular SPEC.COLL specific collective SUB subordinate clause marker TAG tag question marker ZERO person/number reference with no overt realisation - affix boundary = clitic boundary . -

Ditransitive Constructions Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig (Germany) 23-25 November 2007

Conference on Ditransitive Constructions Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig (Germany) 23-25 November 2007 Abstracts On “Dimonotransitive” Structures in English Carmen Aguilera Carnerero University of Granada Ditransitive structures have been prototypically defined as those combinations of a ditransitive verb with an indirect object and a direct object. However, although in the prototypical ditransitive construction in English, both objects are present, there is often omission of one of the constituentes, usually the indirect object. The absence of the indirect object has been justified on the basis of the irrelevance of its specification or the possibility of recovering it from the context. The absence of the direct object, on the other hand, is not so common and only occur with a restricted number of verbs (e.g. pay, show or tell).This type of sentences have been called “dimonotransitives” by Nelson, Wallis and Aarts (2002) and the sole presence in the syntactic structure arises some interesting questions we want to clarify in this article, such as: (a) the degree of syntactic and semantic obligatoriness of indirect objects and certain ditransitive verbs (b) the syntactic behaviour of indirect objects in absence of the direct object, in other words, does the Oi take over some of the properties of typical direct objects as Huddleston and Pullum suggest? (c) The semantic and pragmatic interpretations of the missing element. To carry out our analysis, we will adopt a corpus –based approach and especifically we will use the International Corpus of English (ICE) for the most frequent ditransitive verbs (Mukherjee 2005) and the British National Corpus (BNC) for the not so frequent verbs. -

Transitive Verb

Transitive verb This article needs additional citations for verification. Learn more A transitive verb is a verb that accepts one or more objects. This contrasts with intransitive verbs, which do not have objects. Transitivity is traditionally thought a global property of a clause, by which activity is transferred from an agent to a patient.[1] Transitive verbs can be classified by the number of objects they require. Verbs that accept only two arguments, a subject and a single direct object, are monotransitive. Verbs that accept two objects, a direct object and an indirect object, are ditransitive,[2] or less commonly bitransitive.[3] An example of a ditransitive verb in English is the verb to give, which may feature a subject, an indirect object, and a direct object: John gave Mary the book. Verbs that take three objects are tritransitive.[4] In English a tritransitive verb features an indirect object, a direct object, and a prepositional phrase – as in I'll trade you this bicycle for your binoculars – or else a clause that behaves like an argument – as in I bet you a pound that he has forgotten.[5] Not all descriptive grammars recognize tritransitive verbs.[6] A clause with a prepositional phrase that expresses a meaning similar to that usually expressed by an object may be called pseudo-transitive. For example, the Indonesian sentences Dia masuk sekolah ("He attended school") and Dia masuk ke sekolah ("He went into the school") have the same verb (masuk "enter"), but the first sentence has a direct object while the second has a prepositional phrase in its place.[7] A clause with a direct object plus a prepositional phrase may be called pseudo-ditransitive, as in the Lakhota sentence Haŋpíkčeka kiŋ lená wé-čage ("I made those moccasins for him").[8] Such constructions are sometimes called complex transitive. -

Preposition Stranding Vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation

languages Article Preposition Stranding vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation Christine Günther Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Universität Siegen, 57076 Siegen, Germany; [email protected] Abstract: Grammatical variation has often been said to be determined by cognitive complexity. Whenever they have the choice between two variants, speakers will use that form that is associated with less processing effort on the hearer’s side. The majority of studies putting forth this or similar analyses of grammatical variation are based on corpus data. Analyzing preposition stranding vs. pied-piping in English, this paper sets out to put the processing-based hypotheses to the test. It focuses on discontinuous prepositional phrases as opposed to their continuous counterparts in an online and an offline experiment. While pied-piping, the variant with a continuous PP, facilitates reading at the wh-element in restrictive relative clauses, a stranded preposition facilitates reading at the right boundary of the relative clause. Stranding is the preferred option in the same contexts. The heterogenous results underline the need for research on grammatical variation from various perspectives. Keywords: grammatical variation; complexity; preposition stranding; discontinuous constituents Citation: Günther, Christine. 2021. Preposition Stranding vs. Pied- 1. Introduction Piping—The Role of Cognitive Grammatical variation refers to phenomena where speakers have the choice between Complexity in Grammatical Variation. two (or more) semantically equivalent structural options. Even in English, a language with Languages 6: 89. https://doi.org/ rather rigid word order, some constructions allow for variation, such as the position of a 10.3390/languages6020089 particle, the ordering of post-verbal constituents or the position of a preposition. -

The Relationship Between Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in English Language

NOTION NOTION Volume 01, Number 02, November 2019 p. 62-67 The Relationship between Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in English Language Teddy Fiktorius SMA Bina Mulia Pontianak, Kalimantan Barat, Indonesia [email protected] Article Info ABSTRACT Article History In the current research, the researcher employs descriptive method (library Article Received research) to elaborate on the relationship and differentiation between the 17th August 2019 English language transitive and intransitive verbs. The first parts explore the Article Reviewed theoretical framework of the relationship and differentiation equipped with 9th September 2019 various sentences samples. The next part discusses the implications for English Article Accepted language teachers in coping with some grammatical confusion. Finally, some 11 October 2019 solutions as well as recommendations are proposed. Keywords transitive verbs intransitive verbs grammatical confusion I. INTRODUCTION misleading sentences that lose its exact meaning. Verbs can be so tricky that even the best grammar Students, particularly the speakers of other languages, students might be often confounded by the difference often have difficulty determining which verbs require between transitive and intransitive verbs. The an object, and which do not. When students confuse confusion with the use of the transitive and transitive and intransitive verbs, the sentences they intransitive verbs can be resolved as a grammar point construct both orally and in written may be becomes clear with an understanding of objects. incomplete. When using a dictionary to look up verbs, we may This current paper is written to provide us with have been puzzled by the abbreviations vi (intransitive better insights into the difference of transitive and verb) and vt (transitive verb). -

Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

OTOXXX10.1177/0194599816689667Otolaryngology–Head and Neck SurgeryBhattacharyya et al 6896672017© The Author(s) 2010 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Clinical Practice Guideline Otolaryngology– Head and Neck Surgery Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign 2017, Vol. 156(3S) S1 –S47 © American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update) Surgery Foundation 2017 Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599816689667 10.1177/0194599816689667 http://otojournal.org Neil Bhattacharyya, MD1, Samuel P. Gubbels, MD2, Seth R. Schwartz, MD, MPH3, Jonathan A. Edlow, MD4, Hussam El-Kashlan, MD5, Terry Fife, MD6, Janene M. Holmberg, PT, DPT, NCS7, Kathryn Mahoney8, Deena B. Hollingsworth, MSN, FNP-BC9, Richard Roberts, PhD10, Michael D. Seidman, MD11, Robert W. Prasaad Steiner, MD, PhD12, Betty Tsai Do, MD13, Courtney C. J. Voelker, MD, PhD14, Richard W. Waguespack, MD15, and Maureen D. Corrigan16 Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are associated with undiagnosed or untreated BPPV. Other out- disclosed at the end of this article. comes considered include minimizing costs in the diagnosis and treatment of BPPV, minimizing potentially unnecessary re- turn physician visits, and maximizing the health-related quality Abstract of life of individuals afflicted with BPPV. Action Statements. The update group made strong recommenda- Objective. This update of a 2008 guideline from the American tions that clinicians should (1) diagnose posterior semicircular Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foun- canal BPPV when vertigo associated with torsional, upbeating dation provides evidence-based recommendations to benign nystagmus is provoked by the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, per- paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), defined as a disorder of formed by bringing the patient from an upright to supine posi- the inner ear characterized by repeated episodes of position- tion with the head turned 45° to one side and neck extended al vertigo. -

A Verb Expresses Action Or a State of Being. Verbs Are Classified in 3 Ways

Verbs A verb expresses action or a state of being. Verbs are classified in 3 ways: As helping or main verbs As action or linking verbs As transitive or intransitive verbs 1. Main Verbs and Helping Verbs A helping verb may be separated from the main verb. A verb phrase consists of one main verb and one or more helping verbs. Examples I am reading Gulliver’s Travels. We should have been listening instead of talking. Did she paint the house? Commonly Used Helping Verbs Forms of BE A modal is an auxiliary am, is, are, was, were, verb that is used to be, being, been express an attitude toward the action or state of being of the Forms of HAVE main verb. have, having, has, had MODALS can, could, may, might, Forms of DO must, ought, shall, do, does, did should, will, would Not and the contraction of n’t are never part of a verb phrase Instead, they are adverbs telling to what extent. We did not hear you. We didn’t hear you. 2. Action Verbs and Linking Verbs An action verb expresses either physical or mental activity. A linking verb connects the subject to a word or word group that identifies or describes the subject. Such a word group is called a subject complement. Commonly Used Linking Verbs Forms of Be be were shall have been should be being shall be will have been would be am will be can be could be is has been may be should have been are have been might be would have been was had been must be could have been Other Linking Verbs appear feel look seem sound taste become grow remain smell stay turn Depending on how these words are used in a sentence, they can be classified as linking or action verbs. -

1 SENTENCE PATTERNS a Sentence Is the Smallest Grammatical Unit

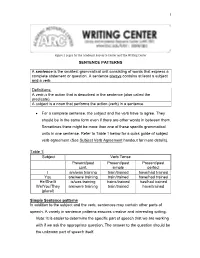

1 Figure 1 Logos for the Academic Resource Center and The Writing Center SENTENCE PATTERNS A sentence is the smallest grammatical unit consisting of words that express a complete statement or question. A sentence always contains at least a subject and a verb. Definitions: A verb is the action that is described in the sentence (also called the predicate). A subject is a noun that performs the action (verb) in a sentence. • For a complete sentence, the subject and the verb have to agree. They should be in the same form even if there are other words in between them. Sometimes there might be more than one of these specific grammatical units in one sentence. Refer to Table 1 below for a quick guide of subject verb agreement (See Subject Verb Agreement handout for more details). Table 1 Subject Verb Tense Present/past Present/past Present/past cont. simple perfect I am/was training train/trained have/had trained You are/were training train/trained have/had trained He/She/It is/was training trains/trained has/had trained We/You/They are/were training train/trained have/trained (plural) Simple Sentence patterns In addition to the subject and the verb, sentences may contain other parts of speech. A variety in sentence patterns ensures creative and interesting writing. Note: It is easier to determine the specific part of speech that we are working with if we ask the appropriate question. The answer to the question should be the unknown part of speech itself. 2 The six major simple sentence patterns are as follows. -

Hypomnemata Glossopoetica

Hypomnemata Glossopoetica Wm S. Annis June 8, 2021 1. Phonology Normally illegal clusters may occur in particular grammatical contexts, and thus look common (cf. Latin -st in 3sg copula est). Hierarchy of codas:1 n < m, ɳ, ŋ < ɳ « l, ɹ < r, ʎ, ʁ < ɭ, ɽ « t < k, p < s, z, c, q, ʃ < b, d, g, x h « w, j. There is a slight place hierarchy: alveolar < velar < retroflex or tap. Classes percolate, such that in complex codas, if Nasals, Resonants and Stops are permitted you usually expect n, r, s, nr, ns and rs as coda sequences. Other orders are possible, but the above rule is common-ish. Hierarchy of clusters (s = sonorant, o = obstruent), word initial: os < oo < ss < so; word final: so < oo < ss < os. Onset clusters tend to avoid identical places of articulation, which leads to avoidance of things like *tl, dl, bw, etc., in a good number of languages. /j/ is lightly disfavored as c2 after dentals, alveolars and palatals; /j/ and palatals are in general disfavored before front vowels. Languages with sC- clusters often have codas. s+stop < s+fric / s+nasal < s+lat < s+rhot (the fricative and nasal are trickier to order). Even if a particular c is a permitted coda, its allowed environment may be quite restricted. Potential con- straints: forbidden before homorganic stop; or homorganic nasal; geminates forbidden. Solutions: delete with compensatory vowel lengthening; debuccalize (become fricative, glottal stop, delete without compensation); nasal deletion with nasalized vowel remaining; tone wackiness. Lower vowels are preferred as syllabic nuclei; high vowels are more prone to syncope (either midword or fi- nally).