SINGAPORE and CHINA's BRANDING PROCESSES By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asia Institute. Records. 1976-2005

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8hq44h9 No online items Asia Institute. Records. 1976-2005. Finding aid prepared by University Archives staff, 2012; finding aid revised by Heather Briston, 2016 January; machine-readable finding aid created by Katharine A. Lawrie, 2016 July. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2015 Asia Institute. Records. University Archives Record Series 788 1 1976-2005. Title: Asia Institute. Records. Identifier/Call Number: University Archives Record Series 788 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 3.2 linear ft.3 cartons, 1 half document box Date: 1976-2005 Abstract: Record Series 788 contains the records of the Asia Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles. Creator: University of California, Los Angeles. Asia Institute. Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Publication Rights Copyright of portions of this collection has been assigned to The Regents of the University of California. The UCLA University Archives can grant permission to publish for materials to which it holds the copyright. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Asia Institute. Records (University Archives Record Series 788). UCLA Library Special Collections, University Archives. Historical Note The Asia Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles was formed in 2003 when the Center for East Asian Studies was combined with the Asia-Pacific Institute. Under the larger umbrella of UCLA's International Institute, the Asia Institute supports East Asian studies at UCLA and the surrounding community through the use of Title VI funds and by providing administrative support to the many centers at UCLA that promote Asian Studies. -

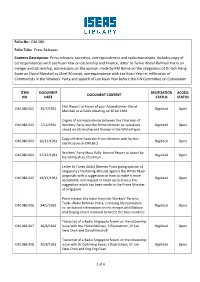

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee by Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S

4 Spotlight Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee By Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong declared in his eulogy at other public figures in Britain, the United States or China, the state funeral for Dr Goh Keng Swee that “Dr Goh was Dr Goh left no memoirs. However, contained within his one of our nation’s founding fathers.… A whole generation speeches and interviews are insights into how he wished of Singaporeans has grown up enjoying the fruits of growth to be remembered. and prosperity, because one of our ablest sons decided to The deepest recollections about Dr Goh must be the fight for Singapore’s independence, progress and future.” personal memories of those who had the opportunity to How do we remember a founding father of a nation? Dr interact with him. At the core of these select few are Goh Keng Swee left a lasting impression on everyone he the members of his immediate and extended family. encountered. But more importantly, he changed the lives of many who worked alongside him and in his public career initiated policies that have fundamentally shaped the destiny of Singapore. Our primary memories of Dr Goh will be through an awareness and understanding of the post-World War II anti-colonialist and nationalist struggle for independence in which Dr Goh played a key, if backstage, role until 1959. Thereafter, Dr Goh is remembered as the country’s economic and social architect as well as its defence strategist and one of Lee Kuan Yew’s ablest and most trusted lieutenants in our narrating of what has come to be recognised as “The Singapore Story”. -

NPP Weekly FLASH Update, April 4, 2000

NPP Weekly FLASH Update, April 4, 2000 Recommended Citation "NPP Weekly FLASH Update, April 4, 2000", NAPSNet Weekly Report, April 04, 2000, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-weekly/npp-weekly-flash-update-april-4-2000/ CONTENTS April 4, 2000 Arms Control 1. ABM Treaty 2. Ratification of START II 3. Arms Control Priorities Nuclear Weapons 1. PRC Nuclear Arsenal 2. US Nuclear Arsenal 3. Pakistan Nuclear Facilities 4. Russian Nuclear Security Military 1. Russian Bombers 2. Pakistan Missiles 3. US Air Force 1 Diplomacy 1. US-Japan Alliance 2. US-PRC Relations Taiwan Straits 1. Cross-Straits Tension 2. Taiwan Government Arms Control 1. ABM Treaty John Holum, US Senior Advisor to the President and Secretary of State for Arms Control said on March 23 that it is in Russia's interest "to avoid putting a U.S. President in a position where he has to choose between defense and the [Anti-Ballistic Missile] Treaty." He added, "We can find a third way, which is to continue the [ABM] Treaty with modest amendments to allow the defense to proceed. I think that strengthens the Treaty, because it demonstrates ... that it is not a barrier to rational adjustments dealing with new security situations." "Transcript: U.S. Official Discusses Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty" Ivo H. Daalder, James M. Goldgeier and James M. Lindsay argue in the Los Angeles Times that Vladimir Putin's election as the new president of Russia opens the door for US President Bill Clinton to negotiate a serious deal on deploying national missile defense (NMD). They called on Clinton to "move decisively to take advantage of this opportunity .. -

Abe's Move Elicited Such a Tepid Response from the Japanese People

China needs to deploy a more silken touch with its neighbours PUBLISHED : Tuesday, 28 July, 2015, 5:30pm UPDATED : Tuesday, 28 July, 2015, 5:34pm Comment›Insight & Opinion Tom Plate Tom Plate says China cannot escape the blame for regional tensions, given its clumsy diplomacy so far Let's play the blame game. Let's bash the Japanese government for ratcheting up tension. Bad, bad Japanese, right? Isn't it just that simple? Since May 3, 1947, Japanese people have lived (and on the whole lived graciously and productively) under the embrace of an American-concocted constitution that with determination tied its defence forces up in restrictive Article 9. But look how well it worked out: Japan became one of the world's greatest economies - until very recently, the No1 economy in Asia. But now Shinzo Abe, working to realise his dream of dumping this iconic and ironic legacy of the second world war in history's dustbin, looks to be on the verge of … triumph! The prime minister has his party and party allies just a legislative click or two away from expanding the leeway (and budget) of the Self-Defence Forces when they have a need to "defend Japan", or help out allies, or whatever. Abe's move elicited such a tepid response from the Japanese people - seemingly far from a gung-ho one in which they pull their samurai swords from the attic Of course, Japan-bashers are quick with the mean-genes argument: isn't it telling that Abe's mother was the daughter of Nobusuke Kishi, who, before becoming the 37th prime minister, distinguished himself as a member of the Tojo cabinet. -

Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions

December 2019 Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions Lauren Dickey, Erica Downs, Andrew Taffer, and Heidi Holz with Drew Thompson, S. Bilal Hyder, Ryan Loomis, and Anthony Miller Maps and graphics created by Sue N. Mercer, Sharay Bennett, and Michele Deisbeck Approved for Public Release: distribution unlimited. IRM-2019-U-019755-Final Abstract This report provides a general map of the information environment of the Pacific Island Countries (PICs). The focus of the report is on the information environment—that is, the aggregate of individuals, organizations, and systems that shape public opinion through the dissemination of news and information—in the PICs. In this report, we provide a current understanding of how these countries and their respective populaces consume information. We map the general characteristics of the information environment in the region, highlighting trends that make the dissemination and consumption of information in the PICs particularly dynamic. We identify three factors that contribute to the dynamism of the regional information environment: disruptors, deficits, and domestic decisions. Collectively, these factors also create new opportunities for foreign actors to influence or shape the domestic information space in the PICs. This report concludes with recommendations for traditional partners and the PICs to support the positive evolution of the information environment. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor or client. Distribution Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. 12/10/2019 Cooperative Agreement/Grant Award Number: SGECPD18CA0027. This project has been supported by funding from the U.S. -

National Day Awards 2019

1 NATIONAL DAY AWARDS 2019 THE ORDER OF TEMASEK (WITH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Temasek (Dengan Kepujian)] Name Designation 1 Mr J Y Pillay Former Chairman, Council of Presidential Advisers 1 2 THE ORDER OF NILA UTAMA (WITH HIGH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Nila Utama (Dengan Kepujian Tinggi)] Name Designation 1 Mr Lim Chee Onn Member, Council of Presidential Advisers 林子安 2 3 THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER [Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang] Name Designation 1 Mr Ang Kong Hua Chairman, Sembcorp Industries Ltd 洪光华 Chairman, GIC Investment Board 2 Mr Chiang Chie Foo Chairman, CPF Board 郑子富 Chairman, PUB 3 Dr Gerard Ee Hock Kim Chairman, Charities Council 余福金 3 4 THE MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL [Pingat Jasa Gemilang] Name Designation 1 Ms Ho Peng Advisor and Former Director-General of 何品 Education 2 Mr Yatiman Yusof Chairman, Malay Language Council Board of Advisors 4 5 THE PUBLIC SERVICE STAR (BAR) [Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Lintang)] Name Designation Chua Chu Kang GRC 1 Mr Low Beng Tin, BBM Honorary Chairman, Nanyang CCC 刘明镇 East Coast GRC 2 Mr Koh Tong Seng, BBM, P Kepujian Chairman, Changi Simei CCC 许中正 Jalan Besar GRC 3 Mr Tony Phua, BBM Patron, Whampoa CCC 潘东尼 Nee Soon GRC 4 Mr Lim Chap Huat, BBM Patron, Chong Pang CCC 林捷发 West Coast GRC 5 Mr Ng Soh Kim, BBM Honorary Chairman, Boon Lay CCMC 黄素钦 Bukit Batok SMC 6 Mr Peter Yeo Koon Poh, BBM Honorary Chairman, Bukit Batok CCC 杨崐堡 Bukit Panjang SMC 7 Mr Tan Jue Tong, BBM Vice-Chairman, Bukit Panjang C2E 陈维忠 Hougang SMC 8 Mr Lien Wai Poh, BBM Chairman, Hougang CCC 连怀宝 Ministry of Home Affairs -

Transcript of Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew's Interview With

TRANSCRIPT OF MINISTER MENTOR LEE KUAN YEW’S INTERVIEW WITH SETH MYDANS OF NEW YORK TIMES & IHT ON 1 SEPTEMBER 2010. Mr Lee: “Thank you. When you are coming to 87, you are not very happy..” Q: “Not. Well you should be glad that you‟ve gotten way past where most of us will get.” Mr Lee: “That is my trouble. So, when is the last leaf falling?” Q: “Do you feel like that, do you feel like the leaves are coming off?” Mr Lee: “Well, yes. I mean I can feel the gradual decline of energy and vitality and I mean generally every year when you know you are not on the same level as last year. But that is life.” Q: “My mother used to say never get old.” Mr Lee: “Well, there you will try never to think yourself old. I mean I keep fit, I swim, I cycle.” Q: “And yoga, is that right? Meditation?” Mr Lee: “Yes.” Q: “Tell me about meditation?” Mr Lee: “Well, I started it about two, three years ago when Ng Kok Song, the Chief Investment Officer of the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation, I knew he was doing meditation. His wife had died but he was completely serene. So, I said, how do you achieve this? He said I meditate everyday and so did my wife and when she was dying of cancer, she was totally 1 serene because she meditated everyday and he gave me a video of her in her last few weeks completely composed completely relaxed and she and him had been meditating for years. -

List of Certain Foreign Institutions Classified As Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms

NOT FOR PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY JANUARY 2001 Revised Aug. 2002, May 2004, May 2005, May/July 2006, June 2007 List of Certain Foreign Institutions classified as Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms The attached list of foreign institutions, which conform to the definition of foreign official institutions on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms, supersedes all previous lists. The definition of foreign official institutions is: "FOREIGN OFFICIAL INSTITUTIONS (FOI) include the following: 1. Treasuries, including ministries of finance, or corresponding departments of national governments; central banks, including all departments thereof; stabilization funds, including official exchange control offices or other government exchange authorities; and diplomatic and consular establishments and other departments and agencies of national governments. 2. International and regional organizations. 3. Banks, corporations, or other agencies (including development banks and other institutions that are majority-owned by central governments) that are fiscal agents of national governments and perform activities similar to those of a treasury, central bank, stabilization fund, or exchange control authority." Although the attached list includes the major foreign official institutions which have come to the attention of the Federal Reserve Banks and the Department of the Treasury, it does not purport to be exhaustive. Whenever a question arises whether or not an institution should, in accordance with the instructions on the TIC forms, be classified as official, the Federal Reserve Bank with which you file reports should be consulted. It should be noted that the list does not in every case include all alternative names applying to the same institution. -

Malaysian Parliament 1965

Official Background Guide Malaysian Parliament 1965 Model United Nations at Chapel Hill XVIII February 22 – 25, 2018 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director ………………………………………………………………… 3 Letter from the Chair ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Background Information ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Background: Singapore ……………………………………………………… 5 Background: Malaysia ……………………………………………………… 9 Identity Politics ………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Radical Political Parties ………………………………………………………………………… 14 Race Riots ……………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Positions List …………………………………………………………………………………… 18 Endnotes ……………………………………………………………………………………… 22 Parliament of Malaysia 1965 Page 2 Letter from the Crisis Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to the Malaysian Parliament of 1965 Committee at the Model United Nations at Chapel Hill 2018 Conference! My name is Annah Bachman and I have the honor of serving as your Crisis Director. I am a third year Political Science and Philosophy double major here at UNC-Chapel Hill and have been involved with MUNCH since my freshman year. I’ve previously served as a staffer for the Democratic National Committee and as the Crisis Director for the Security Council for past MUNCH conferences. This past fall semester I studied at the National University of Singapore where my idea of the Malaysian Parliament in 1965 was formed. Through my experience of living in Singapore for a semester and studying its foreign policy, it has been fascinating to see how the “traumatic” separation of Singapore has influenced its current policies and relations with its surrounding countries. Our committee is going back in time to just before Singapore’s separation from the Malaysian peninsula to see how ethnic and racial tensions, trade policies, and good old fashioned diplomacy will unfold. Delegates should keep in mind that there is a difference between Southeast Asian diplomacy and traditional Western diplomacy (hint: think “ASEAN way”). -

Mrs. Thatcher's Return to Victorian Values

proceedings of the British Academy, 78, 9-29 Mrs. Thatcher’s Return to Victorian Values RAPHAEL SAMUEL University of Oxford I ‘VICTORIAN’was still being used as a routine term of opprobrium when, in the run-up to the 1983 election, Mrs. Thatcher annexed ‘Victorian values’ to her Party’s platform and turned them into a talisman for lost stabilities. It is still commonly used today as a byword for the repressive just as (a strange neologism of the 1940s) ‘Dickensian’ is used as a short-hand expression to describe conditions of squalor and want. In Mrs. Thatcher’s lexicon, ‘Victorian’ seems to have been an interchangeable term for the traditional and the old-fashioned, though when the occasion demanded she was not averse to using it in a perjorative sense. Marxism, she liked to say, was a Victorian, (or mid-Victorian) ideo1ogy;l and she criticised ninetenth-century paternalism as propounded by Disraeli as anachronistic.2 Read 12 December 1990. 0 The British Academy 1992. Thanks are due to Jonathan Clark and Christopher Smout for a critical reading of the first draft of this piece; to Fran Bennett of Child Poverty Action for advice on the ‘Scroungermania’ scare of 1975-6; and to the historians taking part in the ‘History Workshop’ symposium on ‘Victorian Values’ in 1983: Gareth Stedman Jones; Michael Ignatieff; Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall. Margaret Thatcher, Address to the Bow Group, 6 May 1978, reprinted in Bow Group, The Right Angle, London, 1979. ‘The Healthy State’, address to a Social Services Conference at Liverpool, 3 December 1976, in Margaret Thatcher, Let Our Children Grow Tall, London, 1977, p. -

Chapter 24: Asia and the Pacific, 1945-Present

Asia and the Pacific 1945–Present Key Events As you read, look for the key events in the history of postwar Asia. • Communists in China introduced socialist measures and drastic reforms under the leadership of Mao Zedong. • After World War II, India gained its independence from Britain and divided into two separate countries—India and Pakistan. • Japan modernized its economy and society after 1945 and became one of the world’s economic giants. The Impact Today The events that occurred during this time period still impact our lives today. • Today China and Japan play significant roles in world affairs: China for political and military reasons, Japan for economic reasons. • India and Pakistan remain rivals. In 1998, India carried out nuclear tests and Pakistan responded by testing its own nuclear weapons. • Although the people of Taiwan favor independence, China remains committed to eventual unification. World History—Modern Times Video The Chapter 24 video, “Vietnam,” chronicles the history and impact of the Vietnam War. Mao Zedong 1949 1953 1965 Communist Korean Lyndon Johnson Party takes War sends U.S. troops over China ends to South Vietnam 1935 1945 1955 1965 1947 1966 India and Indira Gandhi Pakistan become elected independent prime minister nations of India Indira Gandhi 720 0720-0729 C24SE-860705 11/25/03 7:21 PM Page 721 Singapore’s architecture is a mixture of modern and colonial buildings. Nixon in China 1972 HISTORY U.S. President 1989 2002 Richard Nixon Tiananmen Square China joins World Trade visits China massacre Organization Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World History—Modern 1975 1985 1995 2005 Times Web site at wh.mt.glencoe.com and click on Chapter 24– Chapter Overview to 1979 1997 preview chapter information.