THE WALL STREET JOURNAL. ONLINE January 15, 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

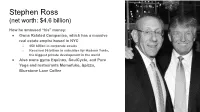

Stephen Ross (Net Worth: $4.6 Billion)

Stephen Ross (net worth: $4.6 billion) How he amassed “his” money: ● Owns Related Companies, which has a massive real estate empire based in NYC ○ $50 billion in corporate assets ○ Received $6 billion in subsidies for Hudson Yards, the biggest private development in the world ● Also owns gyms Equinox, SoulCycle, and Pure Yoga and restaurants Momofuko, &pizza, Bluestone Lane Coffee Stephen Ross (net worth: $7.6 billion) How he keeps “his” money: ● Political donations ○ Raised $12 million for Donald Trump at Hamptons fundraiser ○ Given $80,000 to Andrew Cuomo since 2005 ○ Donates to Republicans in Congress & NYS legislature ● Tax games ○ Billions in tax breaks and other subsidies for Hudson Yards project ○ Overstated value of a property donated to University of Michigan to claim large charitable deduction Stephen Ross (net worth: $7.6 billion) How he spends “his” money: ● At least six homes worth as much as $150 million ○ Hudson Yards penthouse, TriBeCa condo, West Village condo, mansions in the Hamptons and Palm Beach, and a Palm Beach condo ● Owns the Miami Dolphins NFL team ● Board seats at cultural institutions ○ Lincoln Center, Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation Stephen Ross (net worth: $114 billion) How we can tax “his” money: ● Billionaire Wealth Tax ○ Tax on wealth, including unrealized capital gains ● Ultramillionaire Income Tax ○ New 10.32% top PIT rate ● Stock Buyback Tax ○ Hits stunts like his attack on AT&T ● Carried Interest Fairness Fee ○ State tax on his under-taxed fees to investors ● 21st Century Bank Tax ○ State tax on hedge -

990-PF and Its Instructions Is at Www

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491318011814 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947 ( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 0- Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. By law, the 2013 IRS cannot redact the information on the form. Department of the Treasury 0- Information about Form 990-PF and its instructions is at www. irs.gov/form990pf . Internal Revenue Service For calendar year 2013 , or tax year beginning 01 - 01-2013 , and ending 12-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number PAULSON FAMILY FOUNDATION CO PAULSON & CO INC 26-3922995 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite U ieiepnone number (see instructions) 1251 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 50TH FLOOR (212) 956-2221 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here F NEW YORK, NY 10020 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here F r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation E If private foundation status was terminated H Check type of organization Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F_ Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part II, col. -

Document Relates To: ALL ACTIONS ———— REPORT of PAUL GOMPERS, Ph.D

No. 20-222 In the Supreme Court of the United States GOLDMAN SACHS GROUP, INC., ET AL., PETITIONERS v. ARKANSAS TEACHER RETIREMENT SYSTEM, ET AL. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT JOINT APPENDIX (VOLUME 2; PAGES 401-804) KANNON K. SHANMUGAM THOMAS C. GOLDSTEIN PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, GOLDSTEIN & RUSSELL, P.C. WHARTON & GARRISON LLP 7475 Wisconsin Avenue 2001 K Street, N.W. Suite 850 Washington, DC 20006 Bethesda, MD 20814 (202) 223-7300 (202) 362-0636 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel of Record Counsel of Record for Petitioners for Respondents PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI FILED: AUGUST 21, 2020 CERTIORARI GRANTED: DECEMBER 11, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page VOLUME 1 Court of appeals docket entries (No. 18-3667) ................... 1 Court of appeals docket entries (No. 16-250) ..................... 5 District court docket entries (No. 10-3461) ........................ 8 Goldman Sachs 2007 Form 10-K: Conflicts Warning (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 78-6) .................................................... 23 Goldman Sachs 2007 Annual Report: Business Principles (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 143-16) ............................. 30 Financial Times, Markets & Investing, “Goldman’s risk control offers right example of governance,” Dec. 5, 2007 (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 193-20) .......................... 34 Dow Jones Business News, “13 Reasons Bush’s Bailout Won’t Stop Recession,” Dec. 11, 2007 (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 170-24) ................................................ 37 The Wall Street Journal, “How Goldman Won Big on Mortgage Meltdown,” Dec. 14, 2007 (front page) (D. Ct. Hearing Ex. T) ....................................... 42 The New York Times, Off the Shelf, “Economy’s Loss Was One Man’s Gain,” Dec. -

Richest Hedge Funds the World's

THE WORLD’S DR. BROWNSTEIN’S WINNING FORMULA RICHEST PAGE 40 CANYON’S SECRET EMPIRE HEDGE PAGE 56 CASHING IN ON CHAOS FUNDS PAGE 68 February 2011 BLOOMBERG MARKETS 39 100 THE WORLD’S RICHEST HEDGE FUNDS COVER STORIES FOR 20 YEARS, DON BROWNSTEIN TAUGHT philosophy at the University of Kansas. He special- ized in metaphysics, which examines the character of reality itself. ¶ In a photo from his teaching days, he looks like a young Karl Marx, with a bushy black beard and unruly hair. That photo is now a relic standing behind the curved bird’s-eye-maple desk in Brownstein’s corner office in Stamford, Connecticut. Brownstein abandoned academia in 1989 to try to make some money. ¶ The career change paid off. Brownstein is the founder of Structured Portfolio Man- agement LLC, a company managing $2 billion in five partnerships. His flagship fund, the abstrusely named Structured Servicing Holdings LP, returned 50 percent in the first 10 months of 2010, putting him at the top of BLOOMBERG MARKETS’ list of the 100 best-performing hedge CONTINUED ON PAGE 43 DR. BROWNSTEIN’S By ANTHONY EFFINGER and KATHERINE BURTON WINNING PHOTOGRAPH BY BEN BAKER/REDUX FORMULA THE STRUCTURED PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT FOUNDER MINE S ONCE-SHUNNED MORTGAGE BONDS FOR PROFITS. HIS FLAGSHIP FUND’S 50 PERCENT GAIN PUTS HIM AT THE TOP OF OUR ROSTER OF THE BEST-PERFORMING LARGE HEDGE FUNDS. 40 BLOOMBERG MARKETS February 2011 NO. BEST-PERFORMING 1 LARGE FUNDS Don Brownstein, left, and William Mok Structured Portfolio Management FUND: Structured Servicing Holdings 50% 2010 135% 2009 TOTAL RETURN In BLOOMBERG MARKETS’ first-ever THE 100 TOP- ranking of the top 100 large PERFORMING hedge funds, bets on mortgages, gold, emerging markets and global LARGE HEDGE FUNDS economic trends stand out. -

Dodd-Frank's Attempted Reform on Broker-Dealers

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 59 Issue 3 Combating Threats to the International Financial System: The Financial Action Task Article 8 Force January 2015 Kicking the Can Down the Road: Dodd-Frank’s Attempted Reform on Broker-Dealers HELEN QUIGLEY New York Law School, 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Privacy Law Commons, and the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation HELEN QUIGLEY, Kicking the Can Down the Road: Dodd-Frank’s Attempted Reform on Broker-Dealers, 59 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2014-2015). This Note is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 59 | 2014/15 VOLUME 59 | 2014/15 Helen Quigley Kicking the Can Down the Road: Dodd-Frank’s Attempted Reform on Broker-Dealers 59 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 561 (2014–2015) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Helen Quigley was the Managing Editor of the 2013–2014 New York Law School Law Review. She received her J.D. from New York Law School in 2014, and is currently an associate at Venable LLP. www.nylslawreview.com 561 KICKING THE CAN DOWN THE ROAD NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 59 | 2014/15 In the wake of the 2007–2008 financial crisis, and as a result of widespread calls for a reform of the financial regulatory system, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010. -

Hedge Papers, Trump's Wealthcare Plan

HEDGE PAPERS NO.51 Trump’s Wealthcare Plan: Helping Hedge Funds Profit From Soaring Drug Prices 1 INTRODUCTION Trump, Hedge Funds, & the Pharmaceutical Industry In recent weeks, some opponents of the widely criticized Republican healthcare plan have started rebranding it wealthcare, given the mounting evidence that the plan would clearly benefit the wealthiest Americans and given them massive tax cuts. What has been overlooked is the way Trump has already been implementing his own massive wealthcare plan for Wall Street. Indeed, he’s been helping hedge funds profit from higher drug prices and tax dodging at the expense of ordinary Ameri- cans, including those who rely on the quality, affordable healthcare that Republicans will take away if their current bill passes. As a presidential candidate, Trump blasted the pharmaceutical and hedge fund in- dustries, vowing to negotiate lower drug prices for consumers, while declaring that hedge funds were getting away with murder. Yet as President, Trump has increasingly opened his administration to executives from both industries, seeking their advice on special panels and has all but dropped any mention of the vigorous criticisms he levied during his campaign. This report analyzes the outsized influence hedge funds have amassed in the phar- maceutical industry, looking closely at patterns of price gouging and tax dodging at 2 pharmaceutical firms with hedge fund backing, and examining the industry’s close ties to the Trump administration. Indeed, the pharmaceutical industry, and the hedge funds backing it, appear to have identified an opportunity for even greater profit in the Donald Trump presidency. After giving only tepid support during Trump’s campaign, big pharma went all in to court Trump, donating generously to his inauguration and throwing lavish parties in his honor. -

The Credit Derivative Market Meltdown and What Lesson We Can Learn

Department of Real Estate and Construction Management Thesis no. 102 Real Estate Management Master of Science, 30 credits The credit derivative market meltdown and what lesson we can learn A case study of Abacus 2007-AC1 Author: Supervisor: Qin Gao Björn Berggren Stockholm 2011 1 Master of Science thesis Title : The credit derivate market meltdown and what lessons we can learn Author: Qin Gao Department: Department of Real Estate and Construction Management Master Thesis number: 102 Supervisor: Björn Berggren Keywords: CDOs, financial crisis, market failure, adverse selection, agency theory Abstract Credit derivative has become an important financial instrument in global financial market, it plays significant role in transferring credit risk. During the latest financial crisis, collapse of credit derivative market was a main reason led to this worldwide turmoil. In this thesis, I try to investigate this adverse performance through a case study of Goldman Sach's ABACUS 2007-AC1. I conclude three major findings. First, severe interest conflicts and asymmetric information existed between counterparties in credit derivative market in U.S.. Second, the securities‘ credit ratings provided a downward-biased view of their actual default risks, the yields failed to account for the extreme exposure of structured products to declines in aggregate economic conditions. Third, credit derivatives do not eliminate systematic risk, they just shift the risk, CDOs exchanged diversifiable risk for systematic risk during the structuring process, which was difficult to understand for most of investors, we see risk accumulation rather than spreading risk, 2 Acknowledgement I would like to express my thanks to all the teachers in my program, especially Björn Berggren who supervises me at the Royal Institute of Technology (Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan). -

Fund Focus Schroder GAIA Paulson Merger Arbitrage

For professional investors and advisers only Schroders FundFocus Schroder GAIA Paulson Merger Arbitrage Schroders has teamed up with Paulson & Co to offer a fund exploiting the gains to be made from merger arbitrage. We spoke to John Paulson, manager of Schroder GAIA Paulson Merger Arbitrage, to find out how this fund can provide diversification benefits to a portfolio. April 2016 Could you tell us a bit about Paulson & reorganisations, pre-announced deals and frequently, they are difficult and expensive Co and the team involved with this fund? exchange offers, and this broad approach for most investors to research effectively. I founded Paulson & Co in 1994. Since then, provides opportunities in all types of market We attempt to exploit this “informational my team and I have built the firm’s investment conditions. Schroder GAIA Paulson Merger inefficiency” by using our specialist expertise capabilities and infrastructure so that today Arbitrage forms a part of this offering and to undertake detailed fundamental bottom-up it has approximately $14 billion1 under specifically benefits from: analysis to develop a full understanding of the management. We now employ 133 people in risks and rewards surrounding such events. 1. Depth of experience within the New York, London and Hong Kong1. investment team When an analyst identifies a potential All our strategies are based on the same opportunity, he or she will perform an initial 2. Clear expertise and competitive edge underlying investment philosophy and analysis of the company, its industry, peers, objectives: preservation of capital, above 3. A unique, clearly defined strategy that the expected event, and then present their average returns, low volatility and limited has produced uncorrelated returns over findings to the Head of Research and the correlation to the broader markets. -

The Salomon Center for the Study of Financial Institutions and Markets and the NYU Stern Alumni Council Finance Committee Cordially Invite You to Attend The

The Salomon Center for the Study of Financial Institutions and Markets and the NYU Stern Alumni Council Finance Committee cordially invite you to attend the Chats with Financiers Series: A Conversation with John A. Paulson (BS '78) Moderated by Edward Altman, Max L. Heine Professor of Finance, NYU Stern Date September 23, 2008 Time Registration 5:30 - 6:00 pm Presentation and Q & A 6:00 - 7:00 p.m. Reception 7:00 - 9:00 p.m. Location The Puck Building, Grand Ballroom 293 Lafayette Street New York, NY 10012 Cost The fee is waived for Stern students and faculty and guests of the Salomon Center Seating is limited. If you are interested in attending this event, please RSVP to [email protected] About the speaker & moderator John A. Paulson John Paulson (BS '78) is the President and Portfolio Manager of Paulson & Co. Inc., which he founded in 1994. Prior to that, Mr. Paulson was a General Partner of Gruss Partners and a Managing Director in mergers and acquisitions at Bear Stearns. He manages approximately $34 billion in merger, event, and distressed strategies. Mr. Paulson graduated summa cum laude in Finance from NYU Stern in 1978, and received his MBA with high distinction, as a Baker Scholar, from Harvard Business School in 1980. Edward I. Altman Edward I. Altman is the Max L. Heine Professor of Finance at NYU Stern and the Director of Research in Credit and Debt Markets at the NYU Stern Salomon Center for the Study of Financial Institutions. He has been a visiting professor at HEC Paris and Université de Paris-Dauphine in France, the Pontificia Catolica Universidade in Rio de Janeiro, the Australian Graduate School of Management in Sydney, Bocconi University in Milan, and CEMFI in Madrid. -

Consider the Source ©2013 Center for Public Integrity 2 Table of Contents

DIGITAL NEWSBOOK The 2012 election was the most expensive and least trans parent presidential campaign of the modern era. This project seeks to “out” shadowy political organizations that have flourished in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling. As the nation prepares for major state-level elec tions in 2013 and critical midterms in 2014, we provide the narrative behind the flow of money and how professional politicking is influencing a flood of new spending. The Center for Public Integrity SHOW CONTENTS Consider the Source ©2013 Center for Public Integrity 2 Table of Contents PART I: Big bucks flood 2012 PART III: Nonprofits, the election stealth super PACs Introduction 5 Nonprofits outspent super PACs in 2010, trend may continue 51 Top 25 Super PAC donors 6 What the courts said and why Pro-environment group gave we should care 8 grant to conservative nonprofit 57 Stealth spending on the rise PART II: Super PACs crash as 2012 election approaches 61 the parties Drug lobby gave $750,000 to Crossroads political machine pro-Hatch nonprofit in Utah’s U.S. Senate race funded mostly by secret donors 13 63 Finance industry makes up PART IV: Citizens United nearly half of pro-Romney in the states super PAC’s donations 18 Big business prefers GOP over Contribution limits at risk in Democratic super PACs 25 states thanks to Supreme Court 69 Super PAC appeal, give until Wisconsin recall breaks record it ‘feels good’ 31 thanks to outside cash 73 Canadian-owned firm’s mega- Judicial candidates vulnerable donation to super PAC raises -

Hedge Fund Vultures in Puerto Rico HEDGE FUND BILLIONAIRES in PUERTO RICO They Want Huge Profits—And They Will Push Austerity to Secure Them

HEDGE PAPERS No.17 Hedge Fund Vultures in Puerto Rico HEDGE FUND BILLIONAIRES IN PUERTO RICO They want huge profits—and they will push austerity to secure them Hedge funds and billionaire hedge fund managers have swooped into Puerto Rico during a fast-moving economic crisis to prey on the vulnerable island. Several groups of hedge funds and billionaire hedge fund managers have bought up large chunks of Puerto Rican debt at discounts, pushed the island to borrow more, and are driving towards devastating austerity measures. At the same time, they are also using the island as a tax haven. The hedge fund billionaires active in the Puerto Rican debt crisis are the same characters pushing austerity and privatization in New York and across America. They are fueling inequality by demanding low taxes on wealthy investors, higher taxes on working people, lower wages, harsh service cuts and privatization of public schools. Hedge Clippers provides this “scorecard” of 13 hedge funds and top billionaire hedge fund managers active in the Puerto Rican debt crisis to help the public understand exactly how hedge funds are hurting Puerto Rico, New York and America in their effort to extract massive profits from human misery. HEDGE FUNDS & PUERTO RICO: AN INTRODUCTION • Puerto Rico’s debt crisis is coming to a head, as governor declares that debts are “not payable” • Hedge funds and billionaire hedge fund managers own large percentages of Puerto Rican debt • Hedge fund billionaires have pressured Puerto Rico to take on more debt at extremely favorable terms for creditors and are driving towards austerity measures that put creditor interests above human needs • These same hedge funds are also promoting austerity measures and privatization schemes in New York and throughout the US and the world A debt crisis has been unfolding in Puerto Rico for several years, as high levels of borrowing and a declining economy have made it impossible for the island to manage its debt. -

Hourly Rates

HOURLY RATES A Modest Essay about Extraordinary Paychecks Acknowledgments This report was written by Bartlett Naylor. About Public Citizen Public Citizen is a national non-profit organization with more than 225,000 members and supporters. We represent consumer interests through lobbying, litigation, administrative advocacy, research, and public education on a broad range of issues including consumer rights in the marketplace, product safety, financial regulation, safe and affordable health care, campaign finance reform and government ethics, fair trade, climate change, and cor- porate and government accountability. Public Citizen’s Congress Watch 215 Pennsylvania Ave. S.E. Washington, D.C. 20003 P: 202-546-4996 F: 202-547-7392 http://www.citizen.org © 2011 Public Citizen. All rights reserved. Public Citizen Hourly Rates: Comparing Lucrative Lines of Work Contents U.S. vs. the World ........................................................................................................................... 3 Top Earners ..................................................................................................................................... 3 The Long and the Short of the Hedge Fund.................................................................................... 5 Pay Olympics................................................................................................................................... 9 Total Wealth.................................................................................................................................