Reading About the Financial Crisis: a Twenty-One-Book Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perelman, M. (2007). Some Economics of Class. in M. Yates (Ed.), More

Perelman, M. (2007). Some economics of class. In M. Yates (ed.), More unequal: Aspects of class in the United States. New York: Monthly Review Press. How much more will be required before the U.S. public awakes from its political slumber? Tepid action in the workplace, the voting booth, and the streets have allowed the right wing to steamroll revolutionary changes that have remade the entire sociopolitical structure of the United States. Since the election of Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, every Democratic administration with the exception of Lyndon Johnson's has been more conservative—often far more conservative—than the previous Democratic administration. Similarly, every elected Republican administration, with the single exception of George Herbert Walker Bush's, has been more conservative than the previous Republican administration. The deterioration in the distribution of income is a symptom of a far larger problem. Perhaps formulating the situation in the United States might help people understand their class interests as well as reveal who has benefited from the right-wing revolution. Critics of Marx have long taken pleasure in claiming that the rise of the middle class in the United States and other advanced capitalist economies disproves Marx's "predictions" of the course of capitalism. In recent decades, however, the distribution of income in the United States is coming to resemble that of many poor Latin American economies, with a shrinking middle class and an obscene share of wealth going to the richest members of society. Although proponents of the U.S. model pretend that recent economic trends represent a success, in truth they are signs of capitalism's failure. -

Understanding Enron: "It's About Gatekeepers, Stupid"

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2002 Understanding Enron: "It's about Gatekeepers, Stupid" John C. Coffee Jr. Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, Business Organizations Law Commons, and the Law and Economics Commons Recommended Citation John C. Coffee Jr., Understanding Enron: "It's about Gatekeepers, Stupid", 57 BUS. LAW. 1403 (2002). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2117 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Understanding Enron: "It's About the Gatekeepers, Stupid" By John C. Coffee, Jr* What do we know after Enron's implosion that we did not know before it? The conventional wisdom is that the Enron debacle reveals basic weaknesses in our contemporary system of corporate governance.' Perhaps, this is so, but where is the weakness located? Under what circumstances will critical systems fail? Major debacles of historical dimensions-and Enron is surely that-tend to produce an excess of explanations. In Enron's case, the firm's strange failure is becoming a virtual Rorschach test in which each commentator can see evidence confirming 2 what he or she already believed. Nonetheless, the problem with viewing Enron as an indication of any systematic governance failure is that its core facts are maddeningly unique. -

Systemic Risk Through Securitization: the Result of Deregulation and Regulatory Failure

Revised Feb. 9, 2009 Systemic Risk Through Securitization: The Result of Deregulation and Regulatory Failure by Patricia A. McCoy, * Andrey D. Pavlov, † and Susan M. Wachter ‡ Abstract This paper argues that private-label securitization without regulation is unsustainable. Without regulation, securitization allowed mortgage industry actors to gain fees and to put off risks. During the housing boom, the ability to pass off risk allowed lenders and securitizers to compete for market share by lowering their lending standards, which activated more borrowing. Lenders who did not join in the easing of lending standards were crowded out of the market. In theory, market controls in the form of risk pricing could have constrained heightened mortgage risk without additional regulation. But in reality, as the mortgages underlying securities became more exposed to growing default risk, investors did not receive higher rates of return. Artificially low risk premia caused the asset price of houses to go up, leading to an asset bubble and creating a breeding ground for market fraud. The consequences of lax lending were covered up and there was no immediate failure to discipline the markets. The market might have corrected this problem if investors had been able to express their negative views by short selling mortgage-backed securities, thereby allowing fundamental market value to be achieved. However, the one instrument that could have been used to short sell mortgage-backed securities – the credit default swap – was also infected with underpricing due to lack of minimum capital requirements and regulation to facilitate transparent pricing. As a result, there was no opportunity for short selling in the private-label securitization market. -

Capitalism and Risk: Concepts, Consequences, and Ideologies Edward A

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2016 Capitalism and Risk: Concepts, Consequences, and Ideologies Edward A. Purcell New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons, and the Law and Economics Commons Recommended Citation 64 Buff. L. Rev. 23 (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Capitalism and Risk: Concepts, Consequences, and Ideologies EDWARD A. PURCELL, JR.t INTRODUCTION Politically charged claims about both "capitalism" and "risk" became increasingly insistent in the late twentieth century. The end of the post-World War II boom in the 1970s and the subsequent breakup of the Soviet Union inspired fervent new commitments to capitalist ideas and institutions. At the same time structural changes in the American economy and expanded industrial development across the globe generated sharpening anxieties about the risks that those changes entailed. One result was an outpouring of roseate claims about capitalism and its ability to control those risks, including the use of new techniques of "risk management" to tame financial uncertainties and guarantee stability and prosperity. Despite assurances, however, recent decades have shown many of those claims to be overblown, if not misleading or entirely ill-founded. Thus, the time seems ripe to review some of our most basic economic ideas and, in doing so, reflect on what we might learn from past centuries about the nature of both "capitalism" and "risk," the relationship between the two, and their interactions and consequences in contemporary America. -

The Role of Government Affordable Housing Policy in Creating the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 STAFF REPORT U.S

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Darrell Issa (CA-49), Ranking Member The Role of Government Affordable Housing Policy in Creating the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 STAFF REPORT U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 111TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM ORIGINALLY RELEASED JULY 1, 2009 * UPDATED MAY 12, 2010 INTRODUCTION The housing bubble that burst in 2007 and led to a financial crisis can be traced back to federal government intervention in the U.S. housing market intended to help provide homeownership opportunities for more Americans. This intervention began with two government-backed corporations, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which privatized their profits but socialized their risks, creating powerful incentives for them to act recklessly and exposing taxpayers to tremendous losses. Government intervention also created “affordable” but dangerous lending policies which encouraged lower down payments, looser underwriting standards and higher leverage. Finally, government intervention created a nexus of vested interests – politicians, lenders and lobbyists – who profited from the “affordable” housing market and acted to kill reforms. In the short run, this government intervention was successful in its stated goal – raising the national homeownership rate. However, the ultimate effect was to create a mortgage tsunami that wrought devastation on the American people and economy. While government intervention was not the sole cause of the financial crisis, its role was significant and has received too little attention. In recent months it has been impossible to watch a television news program without seeing a Member of Congress or an Administration official put forward a new recovery proposal or engage in the public flogging of a financial company official whose poor decisions, and perhaps greed, resulted in huge losses and great suffering. -

Final Consent Judgment As to Defendant Bank of America Corporation

EXHIBIT A UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION, Plaintiff, 09 Civ. 6829 (JSR) 10 Civ. 0215 (JSR) -against- . ECF Cases BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION, Defendant. FINAL CONSENT JUDGMENT AS TO DEFENDANT BANK OF AMERICA CORPORATION WHEREAS the Securities and Exchange Commission ("Commission") filed an Amended Complaint on October 19. 2009 in the civil action 09 Civ. 6829 (JSR) alleging that defendant Bank of America Corporation ("BAC") violated Section 14 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 ("Exchange Act"), and Rules 14a-3 and 1l4a-9 promulgated thereunder, as a result of its failure adequately to disclose, in connection with the proxy solicitation for the acquisition of Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc. ("Merrill"), information concerning Merri'll's payment of year-end bonuses (the "Bonus Case"); WHEREAS the Commission subsequently filed a Complaint on January 12, 2010 in the civil action 10 Civ. 0215 (JSR) alleging that BAC violated Section 14 of the Exchange Act and Rule 1l4a-9 thereunder as a result of its failure adequately to disclose, in connection with the proxy solicitation for the acquisition of Merrill, information concerning Merrill's losses in the fourth quarter of 2008 (the "Q4 Loss Case") (together with the Bonus Case, the "Actions"); WHEREAS BAC has executed the Consent annexed hereto and incorporated herein for the purpose of settling the Actions before the Court; and I WHEMREAS BAG has entered a general appearance in the Actions, consented to the Court's jurisdiction over it and the subject matter of the Actions, consented to the entry of this Final Consent Judgment as to Defendant Bank of America Corporation ("Final Judgment"), and waived any right to appeal from this Final Judgment in the Actions: I. -

The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Review Volume 2010 | Issue 2 Article 9 5-1-2010 The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D. Guynn Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Randall D. Guynn, The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform, 2010 BYU L. Rev. 421 (2010). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2010/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DO NOT DELETE 4/26/2010 8:05 PM The Global Financial Crisis and Proposed Regulatory Reform Randall D. Guynn The U.S. real estate bubble that popped in 2007 launched a sort of impersonal chevauchée1 that randomly destroyed trillions of dollars of value for nearly a year. It culminated in a worldwide financial panic during September and October of 2008.2 The most serious recession since the Great Depression followed.3 Central banks and governments throughout the world responded by flooding the markets with money and other liquidity, reducing interest rates, nationalizing or providing extraordinary assistance to major financial institutions, increasing government spending, and taking other creative steps to provide financial assistance to the markets.4 Only recently have markets begun to stabilize, but they remain fragile, like a man balancing on one leg.5 The United States and other governments have responded to the financial crisis by proposing the broadest set of regulatory reforms Partner and Head of the Financial Institutions Group, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, New York, New York. -

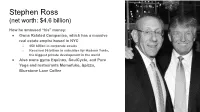

Stephen Ross (Net Worth: $4.6 Billion)

Stephen Ross (net worth: $4.6 billion) How he amassed “his” money: ● Owns Related Companies, which has a massive real estate empire based in NYC ○ $50 billion in corporate assets ○ Received $6 billion in subsidies for Hudson Yards, the biggest private development in the world ● Also owns gyms Equinox, SoulCycle, and Pure Yoga and restaurants Momofuko, &pizza, Bluestone Lane Coffee Stephen Ross (net worth: $7.6 billion) How he keeps “his” money: ● Political donations ○ Raised $12 million for Donald Trump at Hamptons fundraiser ○ Given $80,000 to Andrew Cuomo since 2005 ○ Donates to Republicans in Congress & NYS legislature ● Tax games ○ Billions in tax breaks and other subsidies for Hudson Yards project ○ Overstated value of a property donated to University of Michigan to claim large charitable deduction Stephen Ross (net worth: $7.6 billion) How he spends “his” money: ● At least six homes worth as much as $150 million ○ Hudson Yards penthouse, TriBeCa condo, West Village condo, mansions in the Hamptons and Palm Beach, and a Palm Beach condo ● Owns the Miami Dolphins NFL team ● Board seats at cultural institutions ○ Lincoln Center, Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation Stephen Ross (net worth: $114 billion) How we can tax “his” money: ● Billionaire Wealth Tax ○ Tax on wealth, including unrealized capital gains ● Ultramillionaire Income Tax ○ New 10.32% top PIT rate ● Stock Buyback Tax ○ Hits stunts like his attack on AT&T ● Carried Interest Fairness Fee ○ State tax on his under-taxed fees to investors ● 21st Century Bank Tax ○ State tax on hedge -

After the Meltdown

Tulsa Law Review Volume 45 Issue 3 Regulation and Recession: Causes, Effects, and Solutions for Financial Crises Spring 2010 After the Meltdown Daniel J. Morrissey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel J. Morrissey, After the Meltdown, 45 Tulsa L. Rev. 393 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol45/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Morrissey: After the Meltdown AFTER THE MELTDOWN Daniel J. Morrissey* We will not go back to the days of reckless behavior and unchecked excess that was at the heart of this crisis, where too many were motivated only by the appetite for quick kills and bloated bonuses. -President Barack Obamal The window of opportunityfor reform will not be open for long .... -Princeton Economist Hyun Song Shin 2 I. INTRODUCTION: THE MELTDOWN A. How it Happened One year after the financial markets collapsed, President Obama served notice on Wall Street that society would no longer tolerate the corrupt business practices that had almost destroyed the world's economy. 3 In "an era of rapacious capitalists and heedless self-indulgence," 4 an "ingenious elite" 5 set up a credit regime based on improvident * A.B., J.D., Georgetown University; Professor and Former Dean, Gonzaga University School of Law. This article is dedicated to Professor Tom Holland, a committed legal educator and a great friend to the author. -

Americans for Tax Fairness Selected Opinion Pieces on Corporate Inversions

AMERICANS FOR TAX FAIRNESS SELECTED OPINION PIECES ON CORPORATE INVERSIONS As of October 1, 2014 NATIONAL Fortune – Positively un-American Tax Dodgers, Allan Sloan, July 7, 2014 “Undermining the finances of the federal government by inverting helps undermine our economy. And that’s a bad thing, in the long run, for companies that do business in America.” Fortune – Foreign Tax Ploys Raise a Question: What is an American Company?, Allan Sloan, June 2, 2014 “But in the past few years, as the world has become more global and other countries have cut their corporate rates, a new exodus wave has started. ‘For the past 20 years, there’s been an arms race between the companies on the one hand and the IRS and Congress on the other, and the companies always seem to come up with better weapons,’ says tax expert Bob Willens.” The New York Times – Cracking Down on Corporate Tax Games, The Editorial Board, September 23, 2014 “New rules from the Treasury Department[2] are likely to slow the offensive practice that allows American companies to avoid taxes by merging with foreign rivals. Known as corporate inversions, these are complex, modern variations on the practices of yesteryear, when companies dodged their taxes by moving their addresses to post office boxes in the Caribbean.” The New York Times – At Walgreen, Renouncing Corporate Citizenship, Andrew Ross Sorkin, June 30, 2014 “In Walgreen’s case, an inversion would be an affront to United States taxpayers. The company, which also owns the Duane Reade chain in New York, reaps almost a quarter of -

April 2011 Quarterly Program Topic Report Category: Abortion NOLA: MLNH 010002 Series Title: PBS Newshour Length

April 2011 Quarterly Program Topic Report Category: Abortion NOLA: MLNH 010002 Series Title: PBS NewsHour Length: 60 minutes Airdate: 4/8/2011 6:00:00 PM Service: PBS Format: News Segment Length: 00:10:09 Budget Battle Lines Drawn Over Spending, Planned Parenthood as Shutdown Nears: Federal agencies prepared for a shutdown as negotiators struggled to reach a budget compromise. Jeffrey Brown discusses the latest on the budget talks with Todd Zwillich, Washington correspondent for WNYC radio. Category: Abortion NOLA: MLNH 010015 Series Title: PBS NewsHour Length: 60 minutes Airdate: 4/27/2011 6:00:00 PM Service: PBS Format: News Segment Length: 00:07:47 Budget Battles Reignite Animosity Between Congress, D.C. Government: Kwame Holman reports on the historically tense relations between Congress and the District of Columbia's residents and local politicians. The two worlds collided recently when Congress and President Obama reached a budget agreement in part through provisions affecting abortion services and private- school voucher programs in D.C. Category: Aging NOLA: MLNH 010000 Series Title: PBS NewsHour Length: 60 minutes Airdate: 4/6/2011 6:00:00 PM Service: PBS Format: News Segment Length: 00:06:55 Estrogen Study Lead Researcher on Risks, Benefits of Hormone-Replacement Therapy: Once a popular treatment for menopause symptoms, hormone- replacement therapy had come under scrutiny for raising the risk of certain diseases, but a new study found a reduced risk of breast cancer and other benefits for some women. Jeffrey Brown discusses the latest findings with Dr. Andrea LaCroix, the study's lead author. Category: Aging NOLA: NBRT 030214 Series Title: Nightly Business Report Length: 30 minutes Airdate: 4/28/2011 5:30:00 PM Service: PBS Format: Magazine Segment Length: 00:00:00 Baby Boomers are Working Longer; Baby Boomers, Retirement, and Inheritance; NYSE Says No to Merger Bids; Demand for Nuclear Energy Rises; Preview of Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Meeting; US Economy Slows in First Quarter; Market Focus with Tom Hudson; Market Stats for April 28, 2011. -

990-PF and Its Instructions Is at Www

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491318011814 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947 ( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 0- Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. By law, the 2013 IRS cannot redact the information on the form. Department of the Treasury 0- Information about Form 990-PF and its instructions is at www. irs.gov/form990pf . Internal Revenue Service For calendar year 2013 , or tax year beginning 01 - 01-2013 , and ending 12-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number PAULSON FAMILY FOUNDATION CO PAULSON & CO INC 26-3922995 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite U ieiepnone number (see instructions) 1251 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 50TH FLOOR (212) 956-2221 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here F NEW YORK, NY 10020 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here F r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation E If private foundation status was terminated H Check type of organization Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F_ Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part II, col.