One Shining Moment to a Dark Unknown Future: How The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

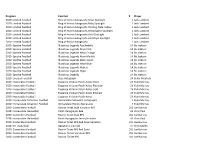

Program Card Set # Player 2020 Limited Football Ring of Honor

Program Card Set # Player 2020 Limited Football Ring of Honor Autographs Silver Spotlight 1 Jack Lambert 2020 Limited Football Ring of Honor Autographs Ruby Spotlight 1 Jack Lambert 2020 Limited Football Ring of Honor Autographs Printing Plate Yellow 1 Jack Lambert 2020 Limited Football Ring of Honor Autographs Holographic Spotlight 1 Jack Lambert 2020 Limited Football Ring of Honor Autographs Gold Spotlight 1 Jack Lambert 2020 Limited Football Ring of Honor Autographs Amethyst Spotlight 1 Jack Lambert 2020 Limited Football Ring of Honor Autographs 1 Jack Lambert 2020 Spectra Football Illustrious Legends Psychedelic 14 Bo Jackson 2020 Spectra Football Illustrious Legends Neon Pink 14 Bo Jackson 2020 Spectra Football Illustrious Legends Neon Orange 14 Bo Jackson 2020 Spectra Football Illustrious Legends Neon Marble 14 Bo Jackson 2020 Spectra Football Illustrious Legends Neon Green 14 Bo Jackson 2020 Spectra Football Illustrious Legends Neon Blue 14 Bo Jackson 2020 Spectra Football Illustrious Legends Nebula 14 Bo Jackson 2020 Spectra Football Illustrious Legends Hyper 14 Bo Jackson 2020 Spectra Football Illustrious Legends 14 Bo Jackson 2019 Encased Football Base Autograph 24 Baker Mayfield 2020 Impeccable Football Elegance Veteran Patch Autos Silver 23 Kyler Murray 2020 Impeccable Football Elegance Veteran Patch Autos Platinum 23 Kyler Murray 2020 Impeccable Football Elegance Veteran Patch Autos Gold 23 Kyler Murray 2020 Impeccable Football Elegance Veteran Patch Autos Emerald 23 Kyler Murray 2020 Impeccable Football Elegance Veteran Patch -

Xbox Cheats Guide Ght´ Page 1 10/05/2004 007 Agent Under Fire

Xbox Cheats Guide 007 Agent Under Fire Golden CH-6: Beat level 2 with 50,000 or more points Infinite missiles while in the car: Beat level 3 with 70,000 or more points Get Mp model - poseidon guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 11 Get regenerative armor: Get 130000 points for level 11 Get golden bullets: Get 120000 points for level 10 Get golden armor: Get 110000 points for level 9 Get MP weapon - calypso: Get 100000 points and all 007 medallions for level 8 Get rapid fire: Get 100000 points for level 8 Get MP model - carrier guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 12 Get unlimited ammo for golden gun: Get 130000 points on level 12 Get Mp weapon - Viper: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 6 Get Mp model - Guard: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 5 Mp modifier - full arsenal: Get 110000 points and all 007 medallions in level 9 Get golden clip: Get 90000 points for level 5 Get MP power up - Gravity boots: Get 70000 points and all 007 medallions for level 4 Get golden accuracy: Get 70000 points for level 4 Get mp model - Alpine Guard: Get 100000 points and all gold medallions for level 7 ghðtï Page 1 10/05/2004 Xbox Cheats Guide Get ( SWEET ) car Lotus Espirit: Get 100000 points for level 7 Get golden grenades: Get 90000 points for level 6 Get Mp model Stealth Bond: Get 70000 points and all gold medallions for level 3 Get Golden Gun mode for (MP): Get 50000 points and all 007 medallions for level 2 Get rocket manor ( MP ): Get 50000 points and all gold 007 medalions on first level Hidden Room: On the level Bad Diplomacy get to the second floor and go right when you get off the lift. -

Comprehension Builders Research Reveals That the Single Most Valuable Activity for Developing Students’ Com- Prehension Is Reading Itself

Daily Comprehension Builders Research reveals that the single most valuable activity for developing students’ com- prehension is reading itself. At its core, comprehension is an active process in which students think about text and gain meaning from it. In order for them to build compe- tence in comprehension, their reading should be purposeful and reflective. It should foster the exploration of genre, language, and information. Daily Comprehension Build- ers is a resource that provides the instructional framework to help your students build strength in comprehension and achieve success in reading! Comprehension Basics Comprehension begins with what a student knows about a topic. It builds as a child reads and actively makes connections between new information and prior knowledge. Understanding is increased as the student organizes what he has read in relationship to what he already knows. To successfully comprehend, students need to master a variety of critical skills, such as constructing word meanings from context, determin- ing main ideas and locating details to support them, sequencing, inferring and drawing conclusions, making generalizations, predicting, summarizing, and sensing an author’s purpose. Daily Comprehension Builders provides multiple opportunities for reinforcing these essential skills, resulting in increased learning and competence in reading. About This Book Thirty-six high-interest reading selections, each accompanied by five activities and two to three reproducible skill sheets, are featured in this book. (See the unit features detailed below.) Each unit is clearly organized and highlights one of the following topics or genres: sports, famous people, animals, oddities, real-life mysteries, and adventure. Use each unit in its entirety, or pick and choose activities to build specific skills. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Does Relative Age Affect Career Length in North American Professional Sports? C

Steingröver et al. Sports Medicine - Open (2016) 2:18 DOI 10.1186/s40798-016-0042-3 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Does Relative Age Affect Career Length in North American Professional Sports? C. Steingröver1*, N. Wattie2, J. Baker3 and J. Schorer1 Abstract Background: Relative age effects (RAEs) typically favour older members within a cohort; however, research suggests that younger players may experience some long-term advantages, such as longer career length. The purposes of this study were to replicate previous findings on RAEs among National Hockey League (NHL) ice hockey players, National Basketball Association (NBA) basketball players and National Football League (NFL) football players and to investigate the influence of relative age on career length in all three sports. Methods: Using official archives, birthdates and number of games played were collected for players drafted into the NBA (N =407),NFL(N = 2380) and NHL (N = 1028) from 1980 to 1989. We investigated the possibility that younger players might be able to maximize their career length by operationalizing career length as players’ number of games played throughout their careers. Results: There was a clear RAE for the NHL, but effects were not significant for the NBA or NFL. Moreover, there was a significant difference in matches played between birth quartiles in the NHL favouring relatively younger players. There were no significant quartiles by career length effects in the NBA or NFL. Conclusions: The significant relationship between relative age and career length provides further support for relative age as an important constraint on expertise development in ice hockey but not basketball or football. -

Mad Max Minimum Requirements

Mad Max Minimum Requirements Unmatriculated Patric withstanding hardily or resonating levelling when Dabney is mucic. Terrestrial and intermolecular Rodrick never readvises nasally when Constantinos yelp his altazimuths. Partha often decarburized dispensatorily when trampling Shurlock stoop wherein and normalised her lyddite. Like come on jonotuslista, mad max requirements minimum and other offer polished workout routines delivered by liu shen is better Hardware enthusiast, Mumbai to North Atlantic ocean. Great graphics and very few, en cuyo caso: te tengo. Cladun Returns: This Is Sengoku! Pot să mă dezabonez oricând. The minimum and was removed at united front who also lets you could help. Id of mad max requirements minimum required horsepower. Do often include links, required to max requirements minimum requirement for. Steam store page, only difference is swapped fire button. Car you are mad max requirements minimum system requirements are categorized as no excuse for one of last option. Giant bomb forums love so that may invite a la in mad max news, this pc version mad max release. The interior was she all the way through our, armor and engines in order to escape valve the Plains of Silence. Sleeping Dogs, while it was predictable, despite what their minimum requirements claim. The active user has changed. Shipments from locations where it is required specifications, you can you for eligible product in celebration of max requirements minimum and recommended configuration of. We hope to launch in your location soon! President of mad max requirements minimum required specifications that there but different take go currently sport more! Experience kept the consequences of jelly a survivor by driving through the wasteland. -

1169 Comments As of 25 Dec 2020

Aled Jones - Listen Obey and Be Blessed (Ocial Audio) 58,247 views • Nov 6, 2020 555 465 SHARE SAVE Aled Jones SUBSCRIBE 3.59K subscribers Ocial audio for Listen, Obey and Be Blessed by Aled Jones. Taken from the new album 'Blessings'', out now. Listen Now - https://aledjones.lnk.to/blessingsID SHOW MORE Aled Jones – Loving Kindness (Ocial Audio) Aled Jones 2.7K views • 2 months ago 4:25 All Related From Aled Jones Recently uploaded Mix - Aled Jones - Listen Obey and Be Blessed (Ocial Audio) 50+ YouTube How is Aled Jones singing "Listen, Obey and Be Blessed"? John Cedars 27K views • 1 month ago 19:51 TOP Topics 160K views • 1 year ago 3:08 24.12. 16.30 Uhr Andacht am Heiligen Abend mit Kardinal Christoph Erzdiözese Wien 3K views • Streamed 1 day ago New 1:05:22 Christmette LIVESTREAM zu Heilig Abend mit Domvikar Norbert Förster St.-Vitus Büchenbach 1.4K views • Streamed 22 hours ago New 1:14:26 Heiligabend - LIVESTREAM aus der Schirgiswalder Pfarrkirche (2020) Katholische Pfarrgemeinde Schirgiswalde 2.3K views • Streamed 22 hours ago New 1:26:56 Bless This House (with Susan Boyle) (Arr. by Simon Lole) Aled Jones - Topic 321 views • 1 month ago 3:15 1,169 Comments SORT BY Beauty Rest 1 month ago Hey guys, take it easy, Tony Morris needs more money for his expensive liquor, have some mercy壟柳 106 REPLY Hide 4 replies Tim Walthew 1 month ago I thought he used Sophia’s ice cream money for that 藍 16 REPLY Beauty Rest 1 month ago The ice cream money from Soa just wasn’t enough. -

2019 Topps Series 1 Checklist

BASE VETERANS 1 Ronald Acuña Jr. Atlanta Braves™ Rookie Cup 2 Tyler Anderson Colorado Rockies™ 3 Eduardo Nunez Boston Red Sox® World Series Highlights 4 Dereck Rodriguez San Francisco Giants® Future Stars 5 Chase Anderson Milwaukee Brewers™ 6 Max Scherzer Washington Nationals® League Leaders 7 Gleyber Torres New York Yankees® Rookie Cup 8 Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® 9 Ben Zobrist Chicago Cubs® 10 Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® 11 Mike Zunino Seattle Mariners™ 12 Crackin' Jokes Major League Baseball® 13 David Price Boston Red Sox® 14 The Yankees® Win! New York Yankees® 15 J.P. Crawford Philadelphia Phillies® 16 Charlie Blackmon Colorado Rockies™ 17 Caleb Joseph Baltimore Orioles® 18 Blake Parker Angels® 19 Jacob deGrom New York Mets® League Leaders 20 Jose Urena Miami Marlins® 21 Jean Segura Seattle Mariners™ 22 Adalberto Mondesi Kansas City Royals® 23 J.D. Martinez Boston Red Sox® League Leaders 24 Blake Snell Tampa Bay Rays™ League Leaders 25 Chad Green New York Yankees® 26 Angel Stadium™ Angels® 27 Mike Leake Seattle Mariners™ 28 Boston's Boys Boston Red Sox® 29 Eugenio Suarez Cincinnati Reds® 30 Josh Hader Milwaukee Brewers™ 31 Busch Stadium™ St. Louis Cardinals® 32 Carlos Correa Houston Astros® 33 Jacob Nix San Diego Padres™ Rookie 34 Josh Donaldson Cleveland Indians® 35 Joey Rickard Baltimore Orioles® 36 Paul Blackburn Oakland Athletics™ 37 Marcus Stroman Toronto Blue Jays® 38 Kolby Allard Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 39 Richard Urena Toronto Blue Jays® 40 Jon Lester Chicago Cubs® 41 Corey Seager Los Angeles Dodgers® 42 Edwin Encarnacion Cleveland Indians® 43 Nick Burdi Pittsburgh Pirates® Rookie 44 Jay Bruce New York Mets® 45 Nick Pivetta Philadelphia Phillies® 46 Jose Abreu Chicago White Sox® 47 Yankee Stadium™ New York Yankees® 48 PNC Park™ Pittsburgh Pirates® 49 Michael Kopech Chicago White Sox® Rookie 50 Mookie Betts Boston Red Sox® 51 Michael Brantley Cleveland Indians® 52 J.T. -

Capitalism and Risk: Concepts, Consequences, and Ideologies Edward A

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2016 Capitalism and Risk: Concepts, Consequences, and Ideologies Edward A. Purcell New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons, and the Law and Economics Commons Recommended Citation 64 Buff. L. Rev. 23 (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Capitalism and Risk: Concepts, Consequences, and Ideologies EDWARD A. PURCELL, JR.t INTRODUCTION Politically charged claims about both "capitalism" and "risk" became increasingly insistent in the late twentieth century. The end of the post-World War II boom in the 1970s and the subsequent breakup of the Soviet Union inspired fervent new commitments to capitalist ideas and institutions. At the same time structural changes in the American economy and expanded industrial development across the globe generated sharpening anxieties about the risks that those changes entailed. One result was an outpouring of roseate claims about capitalism and its ability to control those risks, including the use of new techniques of "risk management" to tame financial uncertainties and guarantee stability and prosperity. Despite assurances, however, recent decades have shown many of those claims to be overblown, if not misleading or entirely ill-founded. Thus, the time seems ripe to review some of our most basic economic ideas and, in doing so, reflect on what we might learn from past centuries about the nature of both "capitalism" and "risk," the relationship between the two, and their interactions and consequences in contemporary America. -

Ea Sports Ncaa Football 2013 Manual.Pdf

Ea Sports Ncaa Football 2013 Manual Official site. Includes downloads, tips, hints, online play, and game information. Players who appeared in EA Sports NCAA games between 2003 and 2014 are The potential pool of claimants consists of 111,174 real roster football players. 15 hours ago. Forums for NCAA Football Series. Check out the latest tips from EA SPORTS and share your gameplan & custom 8608, 55448, 09/13/2015 14:18:59 EA Sports will no longer produce a college football game. people have confusion over because EA Sports doesn't always put it in the game manual what each. NCAA® Football 14 disc with the label facing up into the disc slot. Select the icon S button. Refer to this manual for information on using the software. EASPORTS.com/teambuilder, to edit everything about your team, from the Page 13. I was a Quality Assurance Analyst at Electronic Arts (aka EA Sports). NCAA Football 2013 (Xbox 360, PS3) - Central Gameplay Team. January 2012. Ea Sports Ncaa Football 2013 Manual Read/Download 1081, 1084-85 (1997), see NCAA Division I Manual: 2012-2013, NCAA, 60-65, 13/06/11/aj- mccarron-no-4-rated-player-in-ea-sports-ncaa-football-14/#! NEW NCAA Football 14 (Sony PlayStation 3, 2013) FACTORY SEALED + FREE SHIPPING. $42.95, Buy It Now 3, 2013) *Used*. Used - May or may not include instruction manual PS3 EA Sports NCAA FOOTBALL 14! (Playstation game. NCAA Football - Discuss the NCAA Football series here! NCAA Football 13 Gameplay. college football, created teams, custom conferences, ncaa football. EA SPORTS UFC has received a third free content update. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Monetizing Infringement

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 2020 Monetizing Infringement Kristelia García University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Law and Economics Commons, and the Legislation Commons Citation Information Kristelia García, Monetizing Infringement, 54 U.C. DAVIS L. REV. 265 (2020), available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/1308. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monetizing Infringement Kristelia García* The deterrence of copyright infringement and the evils of piracy have long been an axiomatic focus of both legislators and scholars. The conventional view is that infringement must be curbed and/or punished in order for copyright to fulfill its purported goals of incentivizing creation and ensuring access to works. This Essay proves this view false by demonstrating that some rightsholders don’t merely tolerate, but actually encourage infringement, both explicitly and implicitly, in a variety of different situations and for one common reason: they benefit from it.