8 A-Loris Brownell Tape 1-5-13-2008 Page 1 of 40

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muehlebach Field Dedication July 3, 1923

[page 1] Muehlebach Field Dedication July 3, 1923 Compliments KANSAS CITY BASEBALL CLUB AMERICAN ASSOCIATION [page 2] Proclamation HEY, red-blooded Americans, Fans, EVERYBODY! A new park, Muehlebach Field, dedicated to the great American sport, Baseball, will open Tuesday, July third, Brooklyn Avenue at 22nd. This event will be of interest to all who enjoy clean, healthful, outdoor recreation. The day has gone by when business men look upon a holiday as a lost opportunity. It is now considered an INVESTMENT, as employer and employe alike return, not only with renewed ambition, but with new thoughts and new ideas for which Old Man Success is always on the lookout. For this reason, I recommend that every employer forget the ever present serious side of life and attend the opening baseball game at Muehlebach Field. I also recommend that every employer as far as possible give the same privilege to his employes. To set the example for this recommendation, and to demonstrate its practicality, I declare Tuesday afternoon, July third, a half holiday for all City Hall Employes, beginning at Twelve o’clock (noon). (Signed) FRANK H. CROMWELL, Mayor. -2- [page 3] Program DEDICATORY ADDRESS THOS. J. HICKEY PRESIDENT AMERICAN ASSOCIATION RESPONSE GEO. E. MUEHLEBACH PRESIDENT KANSAS CITY BASEBALL CLUB “KANSAS” GOVERNOR JONATHAN M. DAVIS “MISSOURI” GOVERNOR ARTHUR M. HYDE “KANSAS CITY, MO.” MAYOR FRANK H. CROMWELL Who Will Pitch (Throw) the First Ball “KANSAS CITY, KANSAS" MAYOR W. W. GORDON Who Will Catch? the First Ball FLAG CEREMONY The Stars and Stripes will be raised for the first time over Muehlebach Field BALL GAME 3 P. -

Ou Know What Iremember About Seattle? Every Time Igot up to Bat When It's Aclear Day, I'd See Mount Rainier

2 Rain Check: Baseball in the Pacific Northwest Front cover: Tony Conigliaro 'The great things that took place waits in the on deck circle as on all those green fields, through Carl Yastrzemski swings at a Gene Brabender pitch all those long-ago summers' during an afternoon Seattle magine spending a summer's day in brand-new . Pilots/Boston Sick's Stadium in 1938 watching Fred Hutchinson Red Sox game on pitch for the Rainiers, or seeing Stan Coveleski July 14, 1969, at throw spitballs at Vaughn Street Park in 1915, or Sick's Stadium. sitting in Cheney Stadium in 1960 while the young Juan Marichal kicked his leg to the heavens. Back cover: Posing in 1913 at In this book, you will revisit all of the classic ballparks, Athletic Park in see the great heroes return to the field and meet the men During aJune 19, 1949, game at Sick's Stadium, Seattle Vancouver, B.C., who organized and ran these teams - John Barnes, W.H. Rainiers infielder Tony York barely misses beating the are All Stars for Lucas, Dan Dugdale, W.W. and W.H. McCredie, Bob throw to San Francisco Seals first baseman Mickey Rocco. the Northwestern Brown and Emil Sick. And you will meet veterans such as League such as . Eddie Basinski and Edo Vanni, still telling stories 60 years (back row, first, after they lived them. wrote many of the photo captions. Ken Eskenazi also lent invaluable design expertise for the cover. second, third, The major leagues arrived in Seattle briefly in 1969, and sixth and eighth more permanently in 1977, but organized baseball has been Finally, I thank the writers whose words grace these from l~ft) William played in the area for more than a century. -

NOTICE DRIVE a CHEW CORVAIR Ion Not'60 Issu^ FREE

v'ir • 4 - V FRroAY, JULY 18, 1960 PACT rointTEBav * « ■ iKanrli^Btifr lEo^ttfns Ik ilir N « t MP Hie W M k.-baM - f A - . - l '*Thei^ wiU be no meeUim, of Odd T h e Rev. Alfred L. Williams, JWi»«tfe.l288 F>Hows Lodge tonight The next rector, and the Rev. P r ^ d tt Hospital Not^ L f. w ool 00. rabr M l ooel AbdutTc^Hn meeting 'wiU be Friday, July 22, Beach Jr., assistant, of St, Maty's Episcopal Church will appear oh . iOe p l a n t 1^,123 -'.-'Jiy at 7:80 p.m. The lodge meets on Vlsitiag hours: Adulta. 2 to 8 , i ' r r ; : - ’* . ■ y _ i-j~ ' n g h to wm: H m wM dy daacu conducted by the second and fourth Friday dur the WTSF radio broadeaist, spon 81 MF. ^ . the Recrefttion Department Will be pju. M atonltjr 2 to A aud 8 to 8 ing July and August ' sored* by the Manchester Minis gju. CidldreB's Ward 2 to 7. ■ Cuhet4^rtuheAMoek», MimekMt«r’^ A C ityofV U lageC h »m held tonifbt at- Robertaon Park. terial Assn.,' Sunday at 6:30 p.m. Th^ first dance for children 12 Mrs. Hkrry Doering, 101^ Pine The rector will be in, cdiarge of ^atlarts Today: 180 years end under will beg^ at 7:30 (CUwstfied Adverttalng on Fag* 18) St., has returned hwhe after a 14 broadcasts at 7:10 p.m. dally next iLDMirrSD YESTERDAY: Pat ITAK alBS'^iit, CONN., SATURDAY, JULY 1960 PRICE FIVE and end at 8:80 p.m. -

Latest Doings in Sportland

THE TIMES: JULY 29, 191S LATEST DOINGS IN SPORTLAND FINE TENNIS AT Big Fight Lasted COLONIALS BEAT Demsey's Quick Defeat Only 18 35 Seconds irates Fail 0eror PARK BY 1- -0 SEASIDE Jack Dempsey knocked out Fred MURLINS Fulton in exactly 18 6 seconds In Harrison on Saturday night. Of Fulton Is SOLDIER TEAMS After the bout there was a differ- Chief Bender in Fine Form ence of opinion at the ringside as o Ferguson Surprise to the exact time of the actual Holds Eastern Pitching fighting. Leaguers In- who Several Very Close and Robert Edgren, always to Five Hits. c holds an accurate split-secon- d Schmidt, Fred, However, Says It Was Local Twirls . stop-wat- Mainstay Matches Play- in his hand at import- Hill, p STANDINGS teresting New Haven 29 2-- Blow and Gives ant bouts, is for time. July With Chief 1 a Lucky authority the Americans to Victory 30 1 229 14 3 ers Matched. 5 Bender Totals ..' Evenly "I timed the fight in 18 sec- pitching in wonderful form, was $5,000 to Bind said Over Team-All- ows Two out when winning run Manager onds," Edgren, "and Fulton and the entire team playing brilliant Big League ' ' was on 14- - sec- scored. ; asebal Lieutenant Lemleln and the floor exactly Hits-Sher- 2 Another Match With B Private ball behind him, the Colonials took But Two wood .0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 , onds. He was lifted Bridgeport RESULTS Hennesy are making splendid prog- up by Demp- the second of the series ..0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 ress in the run sey Just four seconds after being game from Pittsburgh Dempsey. -

2018 Media Guide.Indd

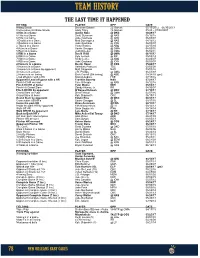

team history the last time it happened HITTING PLAYER OPP DATE Hitting Streak Donovan Solano 22 Games 05/13/2012 – 06/30/2013 Consecutive On Base Streak Andy Tracy 43 Games 05/23 – 07/08/2007 4 Hits in a Game Austin Nola @ OKC 08/29/17 5 Hits in a Game Scott Sizemore @ NAS 05/16/15 6 Hits in a Game Jake Gautreau @ IOW 06/09/07 3 Doubles in a Game Matt Dominguez @ NAS 04/16/12 4 Doubles in a Game Jake Gautreau @ IOW 06/09/07 2 Triples in a Game Vinny Rottino @ ABQ 04/15/10 4 Runs in a Game Xavier Scruggs @ OMA 04/09/16 5 Runs in a Game Josh Kroeger @ OMA 06/02/11 5 RBI in a Game David Vidal @ OMA 06/11/17 6 RBI in a Game Kyle Jensen @ RR 05/05/14 7 RBI in a Game Ricky Ledee @ ABQ 04/24/07 8 RBI in a Game Jake Gautreau @ IOW 06/09/07 2 Homers in a Game Destin Hood @ COS 05/24/17 3 Homers in a Game Valentino Pascucci TUC 08/02/08 3 Homers in a Game by opponent Matt Chapman NAS 09/03/16 4 Homers in a Game J.R. Phillips @ OMA 05/21/97 2 Homers in an Inning Brett Carroll (5th inning) @ ABQ 08/24/10 gm2 Lead off game with a HR Robert Andino FRE 07/15/16 Opponent Lead off game with a HR Franklin Barreto NAS 07/21/17 Pinch Hit HR on road Cole Gillespie @ IOW 04/12/16 Pinch Hit HR at home Tyler Moore IOW 05/02/17 Pinch Hit Grand Slam Sandy Alomar, Jr. -

Connecticut and Its Richard M

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 28, 1960 Average Daily Net Press Run PAGE EIGBTBEh iianr^(Bt(r jEoraituPi For the Week Ended Dee. X4, IMO 13,331 SHOP NOW! Member ef tbe Audit YOUR CHRISTMAS CASH! USE THAT WONDERFUL GIFT CERTHTCATE! Bmwa et ObmOatMi ■A STORE HOURS: VOL. LXXX, NO. Y5 OiNii Hafly Mon. thro Sat. #:S0to5:45 But Door Not Shut Kennedy Wins fln oi» Nights tm 9:00 State New s Hawaii’s Votes; Roundup Ed May Denies Total Now 303 Washington, Dec. 29 — Drivers Warned An official recount in Hawaii Of Freezing Rain H e’s Candidate has tipped the newest state’s three electoral votes to Presi dent-elect John F. Kennedy by Windsor Locks, Dec, 29 Hartford, //p)_.aA. Searle Plnney of Brookfield and 115 votes. — The U.S. Weather Bureau GOP State Chairman Edwin Jewett, who lives In Lyme That gives Kennedy 303 electoral today issued the following "They are people of proven dedi votes to 219 for Vice President snow' and hazardous driving H. May Jr. said today he is cation to Connecticut and its Richard M. Nixon: 269 were need not a candidate for the nomi people and are men of great abil warning for Connecticut: AFTER-CHRISTMAS ed to win. Sen. H arry F. Byrd, D- Light snow this morning be ity,” he continued, “ the party is nation of governor in 1962 Va., got 15. coming mixed with sleet and freez but he didn’t entirely close the fortunate to have so many able, With Hawaii’s new totals, an New Brussels Riots qualified prospective candidates.” ing rain late this afternoon or to door to the possibility. -

Arnel Arnel Shoe Sale

' \ WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 9, 1961 FA«B TWENTY A T e ra g e D a ily N e t P ress Runi- The Weather iitanrIfPBter lEtt^nitt^ For the Week Ended ForecMt of O. S. Wentber Barea* done S, 1961 F air, warm,humid tonight. Low 13,3.S0 66-10. Friday haiy, hot, humid, About Town thnnderahowem In late altemoon. Board Deliays Action HOUSE &. HALE Member of the Aodlt High near 90, HOUSE &, IMLE I>r. Robert E. KUme, a radiolo- BoreMi of drenlstton MAIN STREET — MANCHESTER Manchester— A City of Village Charm MAIN STREET — MANCHESTER I gist at Manchester Memorial Hoa- ^tal. will didCiiM new techniques » • On Appeals Unit Law in radiolog>’ a* guest v f the Kl- MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, AUGUST 10, 1961 (ClaaeUlod Adverttatiig on Page 16) PRICE FIVE CENTS wanis Club of Manchester Tues- VOL. LXXX, NO. 264 (EIGHTEEN PAGES) da.v at noon at the Manchester ' Country Club. The board of directors."after public hearings at Bowers School Auditorium last night, tabled action on a proposed Capt. Paul, W. Arcari. non of ordinance to create a personnel appeals board pending further j Mrs. Magdalene V. Arcari. 182 stud.v, and approved three proposed ordinances. Kennedy Sends Aide State News WONDERFUL! I' Oak St., has been selected to par A fter hearing several aug SALE^ ticipate in the Arm y-Air F\>rce tlona concerning regulationa and consultant On drafting suggested I maneuver, "Exercise Swift Strike," procedures of a personnel appeals rules of procedure. Roundup at Dover Air Force Base. Del., board, the directors decided to de Gunfight Foils Castro Foes this month. -

Fiul$Idc £ Imes

d $ Fair and mild today and to- 1 morrow. J &[)£ fiUl$idc £ imes 'OFFICIAL NEWHPAPKM HILLSIDE, N. J„ THURSDAY; JUNK i/, m lT OF TUE TOWNSHIP OF HILLSIDE PRICE FIVE CENTS - ” Mark 171st Anniversary Of Adoption Of American Fla« See Accredited Rating Threatened If School Facilities Are Inadequate Zoning Ordinance Ballots' in last Tuesday’s referer to debate on the public platform could be done before two years. dum on adding a wing to the high with anyone.'’ school'had hardly been counted be She was informed there was no Leibo criticized the parent-teaeh regulation as to lime. fore sentiment appeared at Thurs er associations for not working hard Revision Proposed day night's meeting of the Board of cn-ugh. He said he was willing to Mrs. Franklin Lange, president of Education either for re-submission abide by the will of the people, but Saybrook School P.T.A.. slated that Mayor Says Changes of the same referendum or some felt the referendum was not an ex as a group the parent teacher asso other plan that would be likely to pression of the people's will and ciations,, could not ring door bells, School Janitors Over Period Of Years meet With the approval of the that the outcome did not leave his a view which was supported by Require Attention voters. a conscience clear. Mrs. Carl Hexamer. also active in Walter Leibu kept the topic alive I don't know what were going P.T.A work. Seek $300 Bonus Necessity for revision of the exist when, as chairman of the board’s In do for schools," hi* continued. -

Spectator 1946-07-05 Editors of the Ps Ectator

Seattle nivU ersity ScholarWorks @ SeattleU The peS ctator 7-5-1946 Spectator 1946-07-05 Editors of The pS ectator Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/spectator Recommended Citation Editors of The peS ctator, "Spectator 1946-07-05" (1946). The Spectator. 317. http://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/spectator/317 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The peS ctator by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. SUMMER SERENADETO BE JULYI2 Deadline for the Removal Spec Introduces of Incompletes V. A.Director O'Connell July 17 (See Page 4) SPECTATORSEATTLE, WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, JULY 5, 1946 NO. 1. VOLUME XIV. Lettermen ChairmanSecond Summer Enrollment Exceeds Former Summer Record SocialWith"Get Acquainted"Mixer On Club InFestive K.C.Ball Room SC Classes Work South Commerce Sliding in to a close secondIin summer social functions The Veterans Swell ' Wing Scheduled Hears Banker, were SC lettermen this week with the announcement of a Siudeni With Record Registration; letter-men sponsored summer mixer. Co-chairman Vince OPA Speaker Pepper and Don Goebel, annoiunced that the mixer will be for Fall ForFallDeadline XC Music will be Chief- Observer Full House Predicted Mack, vice-presi- held in the Rose Room of the i hall. cards this week revealed A report from the President's Mr. Egil tian-styled and carefully aelected By Bill Qulnn A compilation of registration dent of the Seattle First Na- figures have soared over and above all Office verifies the fact that work from the country's better known expressed this column that registration tional bank, and manager of bands, by nickel- "Views in Boasting 281 students more on the fourteen classrooms plan- Foreign Department, Wedding Bells name featured a not necessarily reflect the opin- previous summer enrollments. -

Omise to in Rural Vote

" .'V’A?^^’' ■■ ■■ ’■ *' ■'; ■■' ' .1 • e' ■ V ' , . • VJv BN ■ r-. MONDAY, OCTOBER 1, IM l* jlRattf^»]^r SvMteg l|«ralit • The Wsotbie. - \.-ir. ■■%'■ ■ AVorago DdDy Net FftweaM1 q( O. 0. W iaaiit B i ^ The Amcrlcail liegten Auxiliary Tha Harvest FasUvat fruits and Offlerro of Sunoet Robekoh Our Lady of Fatima Mothara clreft will hold lU drat m o a t^ wilt hold tta regular buslneaa meet vagetablaa an dlaplay at the Sal T roop 112 Plans Parily cloudy, warmer a ^ alW I.,(t<]g« «ill exempUfy tho degreo vation Army clUdel yoaterday, this evening in Odd Fellowa hall of tha aaason at the homa of Mra. ing tf^lght at eight o'clock at the •moon. Fair, lUghtly wantier to- Raymond Tlamey, 2ft Bliaa atTaat, American Legion home. wlU be auctioned off tbU evening Scout-Dad Day whan the Aaaembly offtcera make at 7:8ft Major Benjamin C. fashionable 10572 Bight Wftdnftaday phrtly fSoodr. dMigh; Wednaadav evening at alght b f their official vlalt A pot .luck o'clock. AnS'one intareatad la Join Jonas, together with grocery sta- aatan A ailt warn. supper at aix o'clock w(U pre- The regular meeting of the Mnn- plaa donated by n number of the -Get Acquainted With BcouUng lasr^ _____ ______ wiib the ceremony. A full turnout ing a mothers' circle will be wel cheijter Registered Nurses’ asso Rfonehetfar— City of ViUoffo Charm ■ come to this, meeting. l local merchants. D*y" program Is being planned for . IB Jhme from M » - of the Rebekaha la hoped- f<^r. ciation will be held tomorrow night Sunday, October 14, by membera FABRICS bcM oI. -

Seattle by and By: the Life and Times of Emmett Watson

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2002 Seattle by and by: The life and times of Emmett Watson Erik D. Mickelson The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mickelson, Erik D., "Seattle by and by: The life and times of Emmett Watson" (2002). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5042. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5042 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission _______v No, I do not grant permission__________ Author's Signature:CcLJ$. ^ _____________________ Date: U £ [{jo ______________ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 SEATTLE BY AND BY: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF EMMETT WATSON by Erik D. Mickelson B.S. University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, Wash., 2000 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana October 2002 Approve* lhairperson Dean, Graduate School f| -2-L -o-2_ Date UMI.Number: EP40506 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

White Oak Graduates Class of 2021

The Westfield NewsSearch for The Westfield News Westfield350.com The WestfieldNews Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME IS THE ONLY WEATHER CRITIC WITHOUT TONIGHT AMBITION.” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com VOL. 86 NO. 151 $1.00 WEDNESDAY,TUESDAY, JUNE JUNE 27, 20179, 2021 VOL. 75 cents 90 NO. 134 Southwick has White Oak two new police graduates sergeants By PETER CURRIER Class of 2021 Staff Writer By AMY PORTER SOUTHWICK – The Staff Writer Southwick Select Board WESTFIELD – Ten students graduated from White Oak voted June 7 to promote two School on the afternoon of June 7 in a touching ceremony that Southwick police officers to was moved indoors due to excessive heat. the rank of sergeant following Families were seated in sections in the gymnasium and a remote interview of three applauded as the seniors took their seats at the front, welcomed candidates. by Headmaster David Drake, Student Dean Gerard McGovern Roger P. Arduini and and Academic Dean Jody Michalski. Michael A. Taggart were McGovern said everyone was gathered to celebrate the selected unanimously. David extraordinary accomplishments of the seniors, and quoted P. Massai was also inter- Charles Dickens, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of viewed. times…” to describe the pandemic year. He said despite the In their interviews, both chaos and orientation, and despite the fear of disease, for each men said that they aspire to student the goal of completing their senior year was worth one day become the chief of ROGER P. ARDUINI whatever effort it took.