Manahatta to Manhattan Native Americans in Lower Manhattan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of Occupy Wall Street ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG NEW YORK OFFICE by Ethan Earle Table of Contents

A Brief History of Occupy Wall Street ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG NEW YORK OFFICE By Ethan Earle Table of Contents Spontaneity and Organization. By the Editors................................................................................1 A Brief History of Occupy Wall Street....................................................2 By Ethan Earle The Beginnings..............................................................................................................................2 Occupy Wall Street Goes Viral.....................................................................................................4 Inside the Occupation..................................................................................................................7 Police Evictions and a Winter of Discontent..............................................................................9 How to Occupy Without an Occupation...................................................................................10 How and Why It Happened........................................................................................................12 The Impact of Occupy.................................................................................................................15 The Future of OWS.....................................................................................................................16 Published by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, New York Office, November 2012 Editors: Stefanie Ehmsen and Albert Scharenberg Address: 275 Madison Avenue, Suite 2114, -

The Occupy Wall Street Movement's Struggle Over Privately Owned

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 3162–3181 1932–8036/20170005 A Noneventful Social Movement: The Occupy Wall Street Movement’s Struggle Over Privately Owned Public Space HAO CAO The University of Texas at Austin, USA Why did the Occupy Wall Street movement settle in Zuccotti Park, a privately owned public space? Why did the movement get evicted after a two-month occupation? To answer these questions, this study offers a new tentative framework, spatial opportunity structure, to understand spatial politics in social movements as the interaction of spatial structure and agency. Drawing on opportunity structure models, Sewell’s dual concept of spatial structure and agency, and his concept of event, I analyze how the Occupy activists took over and repurposed Zuccotti Park from a site of consumption and leisure to a space of political claim making. Yet, with unsympathetic public opinion, intensifying policing and surveillance, and unfavorable court rulings privileging property rights over speech rights, the temporary success did not stabilize into a durable transformation of spatial structure. My study not only explains the Occupy movement’s spatial politics but also offers a novel framework to understand the struggle over privatization of public space for future social movements and public speech and assembly in general. Keywords: Occupy Wall Street movement, privately owned public space (POPS), spatial opportunity structure, spatial agency, spatial structure, event Collective actions presuppose the copresence of “large numbers of people into limited spaces” (Sewell, 2001, p. 58). To hold many people, such spaces should, in principle, be public sites that permit free access to everyone. The Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement, targeting the engulfing inequality in the age of financialization and neoliberalization, used occupation of symbolic sites to convey its message. -

Bowling Green Offices Building Designation Report

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 19, 1995, Designation List 266 LP-1927 BOWLING GREEN OFFICES BUILDING, 5-11 Broadway (aka 5-11 Greenwich Street), Manhattan. Built 1895-98; W. & G. Audsley, architects. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 13, Lot 5. On May 16, 1995, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the Bowling Green Offices Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eleven witnesses spoke in favor of designation, including Councilwoman Kathryn Freed and representatives of State Senator Catherine Abate, the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, the Municipal Art Society, the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the Fine Arts Federation, and the Seaport Task Force of Community Board 1. No one spoke in opposition to designation. A representative of the owners took no position regarding the proposed designation but stated that the owners wanted to cooperate with the Commission. The Commission has received several letters and other statements in support of designation including a resolution from Community Board 1. Summary An enormous and beautifully crafted presence at the base of Broadway, facing Bowling Green and extending through the block to Greenwich Street, the seventeen- story Bowling Green Offices Building was designed and built in 1895-98 to be at the forefront of New York commercial towers in terms of its size, architectural style, and amenities. The architects were Scottish-born brothers William James and George Ashdown Audsley, whose fame rests largely on the more than twenty-five books they wrote on craftsmanship, decorative art, and related topics. -

Delaware Indian Land Claims: a Historical and Legal Perspective

Delaware Indian land Claims: A Historical and Legal Perspective DAVID A. EZZO Alden, New York and MICHAEL MOSKOWITZ Wantagh, New York In this paper we shall discuss Delaware Indian land claims in both a histori cal and legal context. The first section of the paper deals with the historical background necessary to understand the land claims filed by the Delaware. In the second part of the paper the focus is on a legal review of the Delaware land claims cases. Ezzo is responsible for the first section while Moskowitz is responsible for the second section. 1. History The term Delaware has been used to describe the descendants of the Native Americans that resided in the Delaware River Valley and other adjacent areas at the start of the 17th century. The Delaware spoke two dialects: Munsee and Unami, both of these belong to the Eastern Algonquian Lan guage family. Goddard has noted that the Delaware never formed a single political unit. He also has noted that the term Delaware was only applied to these groups after they had migrated from their original Northeastern homeland. Goddard sums up the Delaware migration as follows: The piecemeal western migration, in the face of white settlement and its attendant pressures during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, left the Delaware in a number of widely scattered places in Southern Ontario, Western New York, Wisconsin, Kansas and Oklahoma. Their history involves the repeated divisions and consolidations of many villages and of local, political and linguistic groups that developed in complicated and incompletely known ways. In addition, individuals, families and small groups were constantly moving from place to place. -

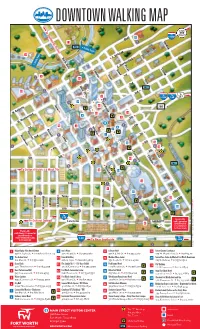

Downtown Walking Map

DOWNTOWN WALKING MAP To To121/ DFW Stockyards District To Airport 26 I-35W Bluff 17 Harding MC ★ Trinity Trails 31 Elm North Main ➤ E. Belknap ➤ Trinity Trails ★ Pecan E. Weatherford Crump Calhoun Grov Jones e 1 1st ➤ 25 Terry 2nd Main St. MC 24 ➤ 3rd To To To 11 I-35W I-30 287 ➤ ➤ 21 Commerce ➤ 4th Taylor 22 B 280 ➤ ➤ W. Belknap 23 18 9 ➤ 4 5th W. Weatherford 13 ➤ 3 Houston 8 6th 1st Burnett 7 Florence ➤ Henderson Lamar ➤ 2 7th 2nd B 20 ➤ 8th 15 3rd 16 ➤ 4th B ➤ Commerce ➤ B 9th Jones B ➤ Calhoun 5th B 5th 14 B B ➤ MC Throckmorton➤ To Cultural District & West 7th 7th 10 B 19 12 10th B 6 Throckmorton 28 14th Henderson Florence St. ➤ Cherr Jennings Macon Texas Burnett Lamar Taylor Monroe 32 15th Commerce y Houston St. ➤ 5 29 13th JANUARY 2016 ★ To I-30 From I-30, sitors Bureau To Cultural District Lancaster Vi B Lancaster exit Lancaster 30 27 (westbound) to Commerce ention & to Downtown nv Co From I-30, h exit Cherry / Lancaster rt Wo (eastbound) or rt Summit (westbound) I-30 To Fo to Downtown To Near Southside I-35W © Copyright 1 Major Ripley Allen Arnold Statue 9 Etta’s Place 17 LaGrave Field 25 Tarrant County Courthouse 398 N. Taylor St. TrinityRiverVision.org 200 W. 3rd St. 817.255.5760 301 N.E. 6th St. 817.332.2287 100 W. Weatherford St. 817.884.1111 2 The Ashton Hotel 10 Federal Building 18 Maddox-Muse Center 26 TownePlace Suites by Marriott Fort Worth Downtown 610 Main St. -

11 Houston Street Greenock PA16 8DA

11 HOUSTON STREET Greenock PA16 8DA Residential Development Opportunity 11 Houston Street Greenock 2 OPPorTUNITY We are delighted to present a site to the market at 11 Houston Street, Greenock which lies close to the Greenock waterfront. The available site extends to approximately 0.35 acres (0.14 hectares) and previously had planning consent for the development of 22 apartments with 26 surfaced car parking spaces. A suite of technical information is available for review upon registration of interest. LOCATION The site is set on the western edge of Greenock Town Centre on Houston Street. Greenock is the largest town within the Local Authority area of Inverclyde. It lies approximately 27 miles west of the City of Glasgow on the southern side of the Firth of Clyde. Greenock has historically been one of the most important Scottish ports and whilst not at the same level of activity as it once was, is still a thriving port and provides docking for Ocean Liners. Greenock provides a wide range of retail and leisure offers within close proximity of the subjects and has excellent road and public transport connections to Glasgow and the surrounding areas. The M8 motorway provides direct access to Glasgow and Edinburgh and Greenock has an extensive rail network with the nearest station to the site being Greenock West station which lies approximately 0.6 miles south east of the subjects. This provides rail connections to Glasgow and Paisley. Ferry Services in nearby Gourock provide passengers and cars with access to Dunoon and Kilcreggan. In close proximity to the subjects there are a number of local amenities such as Ardgowan Bowling Club, Greenock Cricket Club and Greenock Golf Club. -

“We Just Need to Go Egypt on Their Ass!” the Articulation of Labor and Community Organizing in New York City with Occupy Wall Street

“We just need to go Egypt on their ass!” The Articulation of Labor and Community Organizing in New York City with Occupy Wall Street John Krinsky and Paul Getsos DRAFT: PLEASE DO NOT CIRCULATE BEYOND THE WORKSHOP b/c no citations Introduction Most of the people who marched down Broadway on the afternoon of September 17, eventually claiming Zuccotti Park and renaming it Liberty Square, practice activism as opposed to base- building campaign organizing. The difference between these two approaches to social justice work is a crucial one for understanding the tensions and potentials in Occupy Wall Street, and for distinguishing the core of Occupy from the more institutional left, comprised of established labor unions and community-based economic justice organizations. Occupiers focus on direct action and tactics whose aim is to raise awareness about an issue, or to challenge the state and corporate power (most usually by challenging the police or by claiming and occupying both public and private space). The institutional left focuses on building issue-oriented campaigns and leadership development among communities directly and adversely impacted by economic inequality in order to deliver tangible results. One of the things that makes Occupy unusual is that it is one of the few times outside of the global justice demonstrations in Seattle and work around the party conventions, that groups which practice the discipline of organizing worked with activists. Even more unusual is that organizers and activists have worked together over a sustained period of time and have moved from issue to issue and campaign to campaign. Some are very localized, such as work against stop-and-frisk policing in the South Bronx where Occupy Wall Street works with local neighborhood activists, to the Bank of America Campaign, where Occupy Wall Street activists are part of a national campaign where partners include the community organizing network National People’s Action and the faith-based federation of community organizations, PICO. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Lower Manhattan

WASHINGTON STREET IS 131/ CANAL STREETCanal Street M1 bus Chinatown M103 bus M YMCA M NQRW (weekday extension) HESTER STREET M20 bus Canal St Canal to W 147 St via to E 125 St via 103 20 Post Office 3 & Lexington Avs VESTRY STREET to W 63 St/Bway via Street 5 & Madison Avs 7 & 8 Avs VARICK STREET B= YORK ST AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 6 only6 Canal Street Firehouse ACE LISPENARD STREET Canal Street D= LAIGHT STREET HOLLAND AT&T Building Chinatown JMZ CANAL STREET TUNNEL Most Precious EXIT Health Clinic Blood Church COLLISTER STREET CANAL STREET WEST STREET Beach NY Chinese B BEACH STStreet Baptist Church 51 Park WALKER STREET St Barbara Eldridge St Manhattan Express Bus Service Chinese Greek Orthodox Synagogue HUDSON STREET ®0= Merchants’ Fifth Police Church Precinct FORSYTH STREET 94 Association MOTT STREET First N œ0= to Lower Manhattan ERICSSON PolicePL Chinese BOWERY Confucius M Precinct ∑0= 140 Community Plaza Center 22 WHITE ST M HUBERT STREET M9 bus to M PIKE STREET X Grand Central Terminal to Chinatown84 Eastern States CHURCH STREET Buddhist Temple Union Square 9 15 BEACH STREET Franklin Civic of America 25 Furnace Center NY Chinatown M15 bus NORTH MOORE STREET WEST BROADWAY World Financial Center Synagogue BAXTER STREET Transfiguration Franklin Archive BROADWAY NY City Senior Center Kindergarten to E 126 St FINN Civil & BAYARD STREET Asian Arts School FRANKLIN PL Municipal via 1 & 2 Avs SQUARE STREET CENTRE Center X Street Courthouse Upper East Side to FRANKLIN STREET CORTLANDT ALLEY 1 Buddhist Temple PS 124 90 Criminal Kuan Yin World -

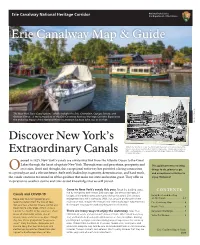

Erie Canalway Map & Guide

National Park Service Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor U.S. Department of the Interior Erie Canalway Map & Guide Pittsford, Frank Forte Pittsford, The New York State Canal System—which includes the Erie, Champlain, Cayuga-Seneca, and Oswego Canals—is the centerpiece of the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor. Experience the enduring legacy of this National Historic Landmark by boat, bike, car, or on foot. Discover New York’s Dubbed the “Mother of Cities” the canal fueled the growth of industries, opened the nation to settlement, and made New York the Empire State. (Clinton Square, Syracuse, 1905, courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Extraordinary Canals Company Collection.) pened in 1825, New York’s canals are a waterway link from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes through the heart of upstate New York. Through wars and peacetime, prosperity and This guide presents exciting Orecession, flood and drought, this exceptional waterway has provided a living connection things to do, places to go, to a proud past and a vibrant future. Built with leadership, ingenuity, determination, and hard work, and exceptional activities to the canals continue to remind us of the qualities that make our state and nation great. They offer us enjoy. Welcome! inspiration to weather storms and time-tested knowledge that we will prevail. Come to New York’s canals this year. Touch the building stones CONTENTS laid by immigrants and farmers 200 years ago. See century-old locks, lift Canals and COVID-19 bridges, and movable dams constructed during the canal’s 20th century Enjoy Boats and Boating Please refer to current guidelines and enlargement and still in use today. -

Lower Manhattan June 25 | 4 Pm – 8 Pm

PART OF THE RIVER TO RIVER FESTIVAL LOWER MANHATTAN JUNE 25 | 4 P.M. – 8 P.M. FREE NIGHTATTHEMUSEUMS.ORG visited visited visited African Burial Ground National Archives at NYC Municipal Archives National Monument New York City 31 Chambers Street (bet. Centre & Elk St.) 290 Broadway (bet. Duane & Reade St.) One Bowling Green (bet. Whitehall & State St.) nyc.gov/records nps.gov/afbg archives.gov/nyc Visitors can tour The Municipal Archives current exhibit, The Lung Block: A New York City Slum & Its The oldest and largest known excavated burial ground Connects visitors to our nation’s history. Our theme Forgotten Italian Immigrant Community. Join co- in North America for both free and enslaved Africans. is Revolutionaries and Rights and the historic strides curators Stefano Morello and Kerri Culhane at 6 p.m. It began to use in the 17th century but was only taken throughout history. Engage with costumed for an exploration of the history of immigrant housing rediscovered in 1991. The story is both of the Africans historical interpreters throughout the building. Stop and reform efforts in NYC at the start of the 20th whose holy place this was, but also the story of the into our Learning Center to discover many of the century through one community. Guests will also see modern-day New Yorkers who fought to honor these national treasures of New York, go on an “Archival a special preview of an upcoming exhibit with the ancestors. Programming: Tour the visitor center, view Adventure,” and pull archival facsimile documents Museum of American Finance opening this fall. -

Tribal and House District Boundaries

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribal Boundaries and Oklahoma House Boundaries ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 22 ! 18 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 13 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 20 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 7 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Cimarron ! ! ! ! 14 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 11 ! ! Texas ! ! Harper ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! n ! ! Beaver ! ! ! ! Ottawa ! ! ! ! Kay 9 o ! Woods ! ! ! ! Grant t ! 61 ! ! ! ! ! Nowata ! ! ! ! ! 37 ! ! ! g ! ! ! ! 7 ! 2 ! ! ! ! Alfalfa ! n ! ! ! ! ! 10 ! ! 27 i ! ! ! ! ! Craig ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! h ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 26 s ! ! Osage 25 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! a ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 16 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 21 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 58 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 38 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes by House District ! 11 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Absentee Shawnee* ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Woodward ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2 ! 36 ! Apache* ! ! ! 40 ! 17 ! ! ! 5 8 ! ! ! Rogers ! ! ! ! ! Garfield ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 40 ! ! ! ! ! 3 Noble ! ! ! Caddo* ! ! Major ! ! Delaware ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! Mayes ! ! Pawnee ! ! ! 19 ! ! 2 41 ! ! ! ! ! 9 ! 4 ! 74 ! ! ! Cherokee ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ellis ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 41 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 72 ! ! ! ! ! 35 4 8 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 5 3 42 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 77