Leon Stefanija Between Autonomy of Music and the Composer’S Autonomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAZU2012.Pdf

ISSN 0374-0315 LETOPIS SLOVENSKE AKADEMIJE ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI 63/2012 THE YEARBOOK OF THE SLOVENIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS VOLUME 63/2012 ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ET ARTIUM SLOVENICAE LIBER LXIII (2012) LETOPIS SAZU_05.indd 1 4.7.2013 9:28:35 LETOPIS SAZU_05.indd 2 4.7.2013 9:28:35 SLOVENSKE AKADEMIJE ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI 63. KNJIGA 2012 THE YEARBOOK OF THE SLOVENIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS VOLUME 63/2012 LJUBLJANA 2013 LETOPIS SAZU_05.indd 3 4.7.2013 9:28:35 SPREJETO NA SEJI PREDSEDSTVA SLOVENSKE AKADEMIJE ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI DNE 21. JANUARJA 2013 Naslov / Address SLOVENSKA AKADEMIJA ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI SI-1000 LJUBLJANA, Novi trg 3, p. p. 323, telefon: (01) 470-61-00 faks: (01) 425-34-23 elektronska pošta: [email protected] spletna stran: www.sazu.si LETOPIS SAZU_05.indd 4 4.7.2013 9:28:35 VSEBINA / CONTENTS I. ORGANIZACIJA SAZU / SASA ORGANIZATION �������������������������������������� 7 Skupščina, redni, izredni, dopisni člani / SASA Assembly, Full Members, Associate Members and Corresponding Members. 9 II. POROČILO O DELU SAZU / REPORT ON THE WORK OF SASA. 17 Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti v letu 2012. 19 Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts in the year 2012 . 25 Delo skupščine ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 31 I. Razred za zgodovinske in družbene vede . 41 II. Razred za filološke in literarne vede . 42 III. Razred za matematične, fizikalne, kemijske in tehniške vede . 43 IV. Razred za naravoslovne vede ������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 45 V. Razred za umetnosti. 46 VI. Razred za medicinske vede ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 50 Kabinet akademika Franceta Bernika . 51 Svet za varovanje okolja ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 51 Svet za energetiko . 51 Svet za kulturo in identiteto prostora Slovenije. -

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Kostka, Stefan

TEN Classical Serialism INTRODUCTION When Schoenberg composed the first twelve-tone piece in the summer of 192 1, I the "Pre- lude" to what would eventually become his Suite, Op. 25 (1923), he carried to a conclusion the developments in chromaticism that had begun many decades earlier. The assault of chromaticism on the tonal system had led to the nonsystem of free atonality, and now Schoenberg had developed a "method [he insisted it was not a "system"] of composing with twelve tones that are related only with one another." Free atonality achieved some of its effect through the use of aggregates, as we have seen, and many atonal composers seemed to have been convinced that atonality could best be achieved through some sort of regular recycling of the twelve pitch class- es. But it was Schoenberg who came up with the idea of arranging the twelve pitch classes into a particular series, or row, th at would remain essentially constant through- out a composition. Various twelve-tone melodies that predate 1921 are often cited as precursors of Schoenberg's tone row, a famous example being the fugue theme from Richard Strauss's Thus Spake Zararhustra (1895). A less famous example, but one closer than Strauss's theme to Schoenberg'S method, is seen in Example IO-\. Notice that Ives holds off the last pitch class, C, for measures until its dramatic entrance in m. 68. Tn the music of Strauss and rves th e twelve-note theme is a curiosity, but in the mu sic of Schoenberg and his fo ll owers the twelve-note row is a basic shape that can be presented in four well-defined ways, thereby assuring a certain unity in the pitch domain of a composition. -

Selective Analysis of 20Th Century Contemporary Percussion Ensembles Designated for Three Or More Players

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1968 Selective analysis of 20th century contemporary percussion ensembles designated for three or more players Raymond Francis Lindsey The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lindsey, Raymond Francis, "Selective analysis of 20th century contemporary percussion ensembles designated for three or more players" (1968). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3513. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SELECTIVE ANALYSIS OF 2 0 ^ CENTURY CONTEMPORARY PERCUSSION ENSEMBLES DESIGNATED FOR THREE OR MORE PLAYERS by Raymond Francis Lindsey B.M* University of Montana 1965 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music University of Montana 1968 Approved by; L L u ' ! JP. 4 . Chairman, Board of Exami4/ers Deah/, Graduate School 1 :: iosa Date UMI Number: EP35093 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

What Is the Sound of Modern Music?

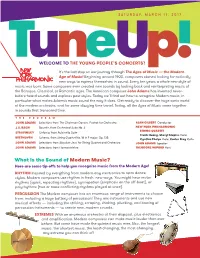

SATURDAY, MARCH 11, 2017 Mozart’s “Classical” European tour? A TuWELCOMEn TO THE YOUNGe PEOPLE’SU CONCERTS!TM p! It’s the last stop on our journey through The Ages of Music — the Modern Age of Music! Beginning around 1900, composers started looking for radically new ways to express themselves in sound. Every ten years a whole new style of music was born. Some composers even created new sounds by looking back and reinterpreting music of the Baroque, Classical, or Romantic ages. The American composer John Adams has invented never- before-heard sounds and explores past styles. Today we’ll find out how to recognize Modern music, in particular what makes Adams’s music sound the way it does. Get ready to discover the huge sonic world of the modern orchestra, and for some dizzying time travel. Today, all the Ages of Music come together in sounds that transcend time. THE PROGRAM JOHN ADAMS Selections from The Chairman Dances, Foxtrot for Orchestra ALAN GILBERT Conductor J.S. BACH Bourrée, from Orchestral Suite No. 3 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC STRING QUARTET STRAVINSKY Sinfonia, from Pulcinella Suite Frank Huang, Sheryl Staples Violin BEETHOVEN Scherzo, from String Quartet No. 16 in F major, Op. 135 Cynthia Phelps Viola; Carter Brey Cello JOHN ADAMS Selections from Absolute Jest, for String Quartet and Orchestra JOHN ADAMS Speaker JOHN ADAMS Selections from Harmonielehre THEODORE WIPRUD Host What Is the Sound of Modern Music? Here are some tip-offs to help you recognize music from the Modern Age! RHYTHM Inspired by everything from modern-day electronics to retro dance styles, Modern composers use rhythm in fresh, new ways. -

20Th CENTURY- the SOUR SWEET MUSIC

20th CENTURY‐ THE SOUR SWEET MUSIC by Winifred Scott Wood Music in the 20th century as in preceding centuries reflects the events surrounding its composers. The big difference is that this century saw more rapid upheaval and revolution than occurred in former times. Artists in all forms of expression seemed compelled to break the boundaries of their predecessors in every way imaginable. This affects harmony, form, rhythm notation and idioms. The general public always tends to lag behind its artist in vision and is loath to give up what has become fondly familiar. Music teachers therefore have even more difficulty in persuading students raised on the harmonious sounds, familiar rhythms and balance forms of pre 20th century composers to venture to the strange seemingly discordant land of contemporary composers. However, as Alan Fluck, author of “The sour Sweet Music” (used as the title of this article) says, “the discords of one generation become concords to the next, because when people get used to discords they consider them concords”. This is very true and gives us a hint as how to introduce students to “new” music without too much “shock” to their system. Students should be made aware of the important role that discords play in the music of the pre20th century composers. Discords add strength and need to be emphasized and even lingered on before this tension is resolved in concords. The word Appoggiatura (a form of discord) means “to lean on”. There is a wealth of music that introduces pianists early in their musical journey to 20th century idioms that is adventurous yet attractive. -

Slovenska Akademija Znanosti in Umetnosti 1938-1988

Nekdanja palača deželnih stanov na Novem trgu št, 3 v Ljubljani, sedež Slovenske akademije znanosti in umetnosti v Ljubljani SLOVENSKA AKADEMIJA ZNANOSTI iN UMETNOSTI Oris in prikaz njenega nastanka in delovanja v jubilejnem petdesetem letu Janez Menart Ljubljana ' 1988 SLOVENSKA AKADEMIJA ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI 1938-1988 Oris in prikaz njenega nastanka in delovanja v jubilejnem petdesetem letu Jubilej Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti praznuje letos petdeseto obletnico svojega obstoja in dela. Po stoletnih željah, občasnih poskusih in večletnih končnih prizadevanjih vse sloven- ske javnosti je bila pravno veljavno ustanovljena leta 1938; uredba o njeni ustanovitvi je bila izdana 11. avgusta in uradno potrjena 31. istega meseca z objavo v »Službenih novinah«; prvi člani so bili v Akademijo imenovani 7. oktobra, prva glavna skupščina sklicana za 12. november in prvi predsednik izvoljen 4. januarja 1939. Ustanovljena je bila akademija kot »osrednja, najvišja in najpopolnejša znanstvena in umetniška ustanova.. kulture slo- venskega naroda«, kot je tedaj pisala slovenska javnost; vendar pa si je morala nadeti le ime »Akademija znanosti in umetnosti v Ljubljani«, ne pa tudi »slovenska«, kajti v tistih letih smo Slovenci veljali samo za pleme jugoslovanskega naroda in sloven- ščina samo za eno od narečij enotnega jugoslovanskega jezika. To ustanovno ime je še danes vklesano na spominski plošči v veži upravne stavbe današnje Slovenske akademije znanosti in umetnosti, ki si je sedanji naziv smela nadeti šele po osvo- boditvi. Leto 1938 pa lahko obvelja kot ustanovno leto Akademije le po najstrožji formalni presoji, le tedaj, ko za priznanje njenega nastanka zahtevamo formalno ustanovitev in gmotno vzdrževanje s strani te ali one države. -

Art Song in the South Slav Territories (1900-1930S): Femininity, Nation and Performance

Creating Art Song in the South Slav Territories (1900-1930s): Femininity, Nation and Performance Verica Grmuša Department of Music Goldsmiths, University of London PhD Thesis The thesis includes a video recording of a full evening lecture-recital entitled ‘Performing the “National” Art Song Today – Songs by Miloje Milojević and Petar Konjović’ (November 22nd, 2017, Deptford Town Hall, Verica Grmuša, soprano, Mina Miletić, piano) 1 Declaration This unpublished thesis is copyright of the author. The thesis is written as a result of my own research work and includes nothing that is written in collaboration with other third party. Where contributions of others are involved, every effort is made to indicate this clearly with reference to the literature, interviews or other sources. The thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has been already submitted to another qualification or previously published. Signed: ____________________________ Date: __________________ Verica Grmuša 2 Acknowledgments I express my gratitude to Goldsmiths’ Music Department, the Postgraduate Research Committee and the Graduate School for their awards and support for my research. I express my gratitude to my supervisors, Dr Berta Joncus and Dr Dejan Djokić, for their specialist help which greatly shaped this thesis. I am indebted to Nan Christie for her indispensable vocal tuition and support during my studies. I am indebted to the late Professor Vlastimir Trajković for access to the Miloje Milojević Family Collection, and for his support and guidance. I would also like to thank a number of friends and colleagues for their support and advice at different stages during my studies: Richard Shaw, Aleksandar Vasić, Tijana Miletić, Melita Milin, Anthony Pryer, Stephen Smart, Nada Bezić, Davor Merkaš, Slobodan Varsaković, Sarah Collins. -

The Future of Theory

The Future of Theory Editor's Introduction. Graduate students ask questions. They seek a place in a field with which they are coming to terms. Graduate students connect their familiar extra-theoretical worlds with their newly-chosen discipline. They develop a collegial unity not only from common interests but also through shared situations and the transitional aspect of their circumstance. And graduate students are willing to take risks, to try out new territory without knowing what lies out there. The following article came about from the ideas of graduate students in music theory at Indiana University. Current topics at our noon-time forums (brown-bag lunches in the shared office) in January 1990 included popular predictions, not only for the new year but also for the new decade and impending new century. It was a logical step to wonder about the forecast for music theory. We decided to take our musings beyond our graduate student life and ask our more experienced colleagues in the field for their forecasts. Our list was compiled of prominent theorists known for their publications and reflecting a range of ages and interests. (Our own excellent theory faculty was excluded from the list to increase the available space. Those faculty members consulted during the planning of this project approved of our decision.) The Editorial Board decided to ask more rather than fewer theorists as we did not know how many would have time or inclination to respond. The letter sent to these theorists requested their opinions of the "future and course of music theory." Respondents were told not to be limited to that subject if other topics were on their minds. -

Musikgeschichte in Mittel- Und Osteuropa

Musikgeschichte in Mittel- und Osteuropa Musikgeschichte in Mittel- und Osteuropa Mitteilungen der internationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft an der Universit¨at Leipzig Heft 10 in Zusammenarbeit mit den Mitgliedern der internationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur¨ die Musikgeschichte in Mittel- und Osteuropa an der Universit¨at Leipzig herausgegeben von Helmut Loos und Eberhard M¨oller Redaktion Hildegard Mannheims Gudrun Schr¨oder Verlag Leipzig 2005 Gedruckt mit Unterstutzung¨ des Beauftragten der Bundesregierung fur¨ Angelegenheiten der Kultur und der Medien c 2005 by Gudrun Schr¨oder Verlag, Leipzig Redaktion und Satz: Hildegard Mannheims Kooperation: Rhytmos Verlag, PL 61-606 Pozna´n,Grochmalickiego 35/1 Alle Rechte, Nachdruck, auch auszugsweise, nur mit ausdrucklicher¨ Genehmigung des Verlags. Printed in Poland ISBN 3-926196-45-9 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort . IX Briefkorrespondenzen Vladimir Gurewitsch Der Briefwechsel von Jacob von St¨ahlin . 1 Urve Lippus Elmar Arro's letters to Karl Leichter . 12 Vita Lindenberg J^azeps V^ıtols (Wihtol) Briefe aus Riga, Lub¨ eck und Danzig an Irena, Narvaite (1940{1947) . 22 Jur¯ ate_ Burokaite_ Briefe von Mikalojus Konstantinas Ciurlionisˇ und ande- ren Musikern aus Leipzig nach Litauen (1901{1924) . 27 Ma lgorzata Janicka-S lysz The Letters of Grazyna_ Bacewicz and Vytautas Bace- viˇcius . 32 Ma lgorzata Perkowska-Waszek The letters of Ignacy Jan Paderewski as a source of knowledge concerning cultural relationships in Europe . 43 Karol Bula Gregor Fitelbergs Korrespondenz aus den Jahren 1945 bis 1953 . 57 Jelena Sinkewitsch Das Leipziger Konservatorium in den Briefen von My- kola Witalijowytsch Lyssenko (1867{1869) . 63 Luba Kyyanovska Die Briefe von Vasyl Barvins'kyj aus Prag als Spiegel des Musiklebens vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg (1905{1914) 72 Marianna Kopitsa Die neuen quellenkundlichen Studien in der Ukraine im Spiegel des epistolaren Erbes von Reinhold Glier und Boris Lyatoschinski .