Independent State of Papua New Guinea Health System Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gulf & Western Provinces

© Lonely Planet Publications 200 Gulf & Western Provinces GULF & WESTERN PROVINCES GULF & WESTERN PROVINCES Rain drenched, sparsely populated and frighteningly remote, the Gulf and Western Provinces are the Wild West of PNG. A vast and mangrove-pocked coastline arches around the Gulf of Papua from one isolated community to the next. Inland the rich wetlands and seasonally flooded grasslands eventually give rise to the foothills and mountains of the Highlands. Locals hardy enough to survive the thriving population of malarial mosquitoes and end- less meals of sago get around by foot, canoe and small plane. There is barely a sealed road to be found, and roads of any description are rare. Because of this limited infrastructure, few travellers reach the area and even fewer do so independently. Those that do seldom venture far beyond the sleepy provincial capitals of Kerema and Daru, which attract a small, but growing, trickle of nature enthusiasts. In the forests and riverside wetlands around Kiunga and Tabubil, adventurers are discover- ing a dizzying array of some of the island’s most exotic birds. Similarly, two of the country’s greatest rivers, the Fly and the Strickland, along with Tonda Wildlife Management Area, are receiving rave reviews from fishermen with the resources and tenacity to get there. In the remote northwest corner of Western Province, the Ok Tedi Mine is of major eco- nomic importance to Papua New Guinea, and subject to considerable litigation by traditional landowners who are concerned about environmental degradation and the validity of royalty payment calculations. In a country often considered the last frontier for adventure seeking travellers, it is only fitting that these provinces have the final word in the Papua New Guinea section of this book. -

Health&Medicalinfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 HEALTH and MEDICAL

HEALTH AND MEDICAL INFORMATION The American Embassy assumes no responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons, centers, or hospitals appearing on this list. The names of doctors are listed in alphabetical, specialty and regional order. The order in which this information appears has no other significance. Routine care is generally available from general practitioners or family practice professionals. Care from specialists is by referral only, which means you first visit the general practitioner before seeing the specialist. Most specialists have private offices (called “surgeries” or “clinic”), as well as consulting and treatment rooms located in Medical Centers attached to the main teaching hospitals. Residential areas are served by a large number of general practitioners who can take care of most general illnesses The U.S Government assumes no responsibility for payment of medical expenses for private individuals. The Social Security Medicare Program does not provide coverage for hospital or medical outside the U.S.A. For further information please see our information sheet entitled “Medical Information for American Traveling Abroad.” IMPORTANT EMERGENCY NUMBERS AMBULANCE/EMERGENCY SERVICES (National Capital District only) Police: 112 / (675) 324-4200 Fire: 110 St John Ambulance: 111 Life-line: 326-0011 / 326-1680 Mental Health Services: 301-3694 HIV/AIDS info: 323-6161 MEDEVAC Niugini Air Rescue Tel (675) 323-2033 Fax (675) 323-5244 Airport (675) 323-4700; A/H Mobile (675) 683-0305 Toll free: 0561293722468 - 24hrs Medevac Pacific Services: Tel (675) 323-5626; 325-6633 Mobile (675) 683-8767 PNG Wide Toll free: 1801 911 / 76835227 – 24hrs Health&MedicalInfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 AMR Air Ambulance 8001 South InterPort Blvd Ste. -

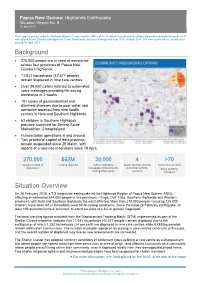

Background Situation Overview

Papua New Guinea: Highlands Earthquake Situation Report No. 8 20 April 2018 This report is produced by the National Disaster Centre and the Office of the Resident Coordinator in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued by the Disaster Management Team Secretariat, and covers the period from 10 to 16 April 2018. The next report will be issued on or around 26 April 2018. Background • 270,000 people are in need of assistance across four provinces of Papua New Guinea’s highlands. • 11,041 households (42,577 people) remain displaced in nine care centres. • Over 38,000 callers listened to automated voice messages providing life-saving assistance in 2 weeks • 181 cases of gastrointestinal and diarrheal diseases due to poor water and sanitation reported from nine health centres in Hela and Southern Highlands. • 62 children in Southern Highlands province screened for Severe Acute Malnutrition; 2 hospitalized. • Humanitarian operations in and around Tari, provincial capital of Hela province, remain suspended since 28 March, with reports of a new rise in tensions since 19 April. 270,000 $62M 38,000 4 >70 people in need of funding required callers listened to health facilities started metric tons of relief assistance messages containing life- providing nutrition items awaiting saving information services transport Situation Overview On 26 February 2018, a 7.5 magnitude earthquake hit the Highlands Region of Papua New Guinea (PNG), affecting an estimated 544,000 people in five provinces – Enga, Gulf, Hela, Southern Highlands and Western provinces, with Hela and Southern Highlands the most affected. More than 270,000 people, including 125,000 children, have been left in immediate need of life-saving assistance. -

0=AFRICAN Geosector

2= AUSTRALASIA geosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 123 2=AUSTRALASIA geosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This geosector covers 223 sets of languages (1167 outer languages, composed of 2258 inner languages) spoken or formerly spoken by communities in Australasia in a geographic sequence from Maluku and the Lesser Sunda islands through New Guinea and its adjacent islands, and throughout the Australian mainland to Tasmania. They comprise all languages of Australasia (Oceania) not covered by phylosectors 3=Austronesian or 5=Indo-European. Zones 20= to 24= cover all so-called "Papuan" languages, spoken on Maluku and the Lesser Sunda islands and the New Guinea mainland, which have been previously treated within the "Trans-New Guinea" hypothesis: 20= ARAFURA geozone 21= MAMBERAMO geozone 22= MANDANGIC phylozone 23= OWALAMIC phylozone 24= TRANSIRIANIC phylozone Zones 25= to 27= cover all other so-called "Papuan" languages, on the New Guinea mainland, Bismarck archipelago, New Britain, New Ireland and Solomon islands, which have not been treated within the "Trans-New Guinea" hypothesis: 25= CENDRAWASIH geozone 26= SEPIK-VALLEY geozone 27= BISMARCK-SEA geozone Zones 28= to 29= cover all languages spoken traditionally across the Australian mainland, on the offshore Elcho, Howard, Crocodile and Torres Strait islands (excluding Darnley island), and formerly on the island of Tasmania. An "Australian" hypothesis covers all these languages, excluding the extinct and little known languages of Tasmania, comprising (1.) an area of more diffuse and complex relationships in the extreme north, covered here by geozone 28=, and (2.) a more closely related affinity (Pama+ Nyungan) throughout the rest of Australia, covered by 24 of the 25 sets of phylozone 29=. -

Notes on the Gulf Province Languages Overview

Notes on the Gulf Province languages Karl Franklin (Data Collected 1968-1973; this report collated 2011) Information compiled here is from notes that I collected between 1968 and 1973. Following the completion of my Ph.D. degree at the Australian National University in 1969, I was awarded a post-doctoral fellowship in 1970 to conduct a linguistic survey of the Gulf Province. In preparation for the survey I wrote a paper that was published as: Franklin, Karl J. 1968. Languages of the Gulf District: A Preview. Pacific Linguistics, Series A, 16.19-44. As a result of the linguistic survey in1970, I edited a book with ten chapters, written by eight different scholars (Franklin, Lloyd, MacDonald, Shaw, Wurm, Brown, Voorhoeve and Dutton). From this data I proposed a classification scheme for 33 languages. For specific details see: Franklin, Karl J. 1973 (ed.) The linguistic situation in the Gulf District and adjacent areas, Papua New Guinea. Pacific Linguistics, Series C, 26, x + 597 pp. Overview There are three sections in this paper. The first is a table that briefly outlines information on languages, dialects and villages of the Gulf Province. (Note that I cannot verify the spelling of each village/language due to differences between various sources.) The second section of the paper is an annotated bibliography and the third is an Appendix with notes from Annual Reports of the Territory of Papua. Source Notes Author/Language Woodward Annual pp. 19-22 by Woodward notes that: Report (AR) Four men of Pepeha were murdered by Kibeni; there is 1919-20:19- now friendly relations between Kirewa and Namau; 22 information on patrols to Ututi, Sirebi, and Kumukumu village on a whaleboat. -

Stories from the Subsurface of Orokolo Bay, Papua New Guinea

Article Journal of Social Archaeology 2019, Vol. 19(3) 279–306 ! The Author(s) 2019 Excavating and Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions interpreting ancestral DOI: 10.1177/1469605319845441 action: Stories from the journals.sagepub.com/home/jsa subsurface of Orokolo Bay, Papua New Guinea Chris Urwin The Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, Monash University, Australia Abstract The Gulf of Papua, Papua New Guinea, is a rapidly changing geomorphic and cultural landscape in which the ancestral past is constantly being (re)interpreted and negotiated. This paper examines the importance of subsurface archaeological and geomorphological features for the various communities of Orokolo Bay in the Gulf of Papua as they maintain and re-construct cosmological and migration narratives. The everyday prac- tices of digging and clearing for agriculture and house construction at antecedent village locations bring Orokolo Bay locals into regular engagement with buried pottery sherds (deposited during the ancestral hiri trade) and thin strata of ‘black sand’ (iron sand). Local interpretations and imaginings of the subsurface enable spatio-temporal interpret- ations of the ancestors’ actions and the structure of ancestral settlements. These interpretations point to the profound entanglement of orality and material culture and suggest new directions in the comparative study of alternative archaeologies. Keywords Indigenous archaeology, oral tradition, hiri, memory work, social memory, Papua New Guinea, Pacific Corresponding author: Chris Urwin, Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, 20 Chancellor’s Walk, Monash University Clayton Campus, Victoria, 3800, Australia. Email: [email protected] 280 Journal of Social Archaeology 19(3) Imagining the subsurface Encounters with and interpretations of subsurface cultural materials and stratig- raphy are often couched as the domain of the Western science of archaeology. -

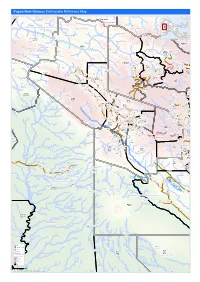

Earthquake Reference Map

Papua New Guinea: Earthquake Reference Map Telefomin London Rural Lybia Telefomin Tunap/Hustein District Ambunti/Drekikier District Kaskare Akiapjmin WEST SEPIK (SANDAUN) PROVINCE Karawari Angoram EAST SEPIK PROVINCE Rural District Monduban HELA PROVINCE Wundu Yatoam Airstrip Lembana Kulupu Malaumanda Kasakali Paflin Koroba/Kopiago Kotkot Sisamin Pai District Emo Airstrip Biak Pokale Oksapmin Liawep Wabag Malandu Rural Wayalima District Hewa Airstrip Maramuni Kuiva Pauteke Mitiganap Teranap Lake Tokom Rural Betianap Puali Kopiago Semeti Oksapmin Sub Aipaka Yoliape Waulup Oksapmin District ekap Airport Rural Kenalipa Seremty Divanap Ranimap Kusanap Tomianap Papake Lagaip/Pogera Tekin Winjaka Airport Gawa Eyaka Airstrip Wane 2 District Waili/Waki Kweptanap Gaua Maip Wobagen Wane 1 Airstrip aburap Muritaka Yalum Bak Rural imin Airstrip Duban Yumonda Yokona Tili Kuli Balia Kariapuka Yakatone Yeim Umanap Wiski Aid Post Poreak Sungtem Walya Agali Ipate Airstrip Piawe Wangialo Bealo Paiela/Hewa Tombaip Kulipanda Waimalama Pimaka Ipalopa Tokos Ipalopa Lambusilama Rural Primary Tombena Waiyonga Waimalama Taipoko School Tumundane Komanga ANDS HIG PHaLin Yambali Kolombi Porgera Yambuli Kakuane C/Mission Paiela Aspiringa Maip Pokolip Torenam ALUNI Muritaka Airport Tagoba Primary Kopetes Yagoane Aiyukuni SDA Mission Kopiago Paitenges Haku KOPIAGO STATION Rural Lesai Pali Airport School Yakimak Apostolic Mission Politika Tamakale Koemale Kambe Piri Tarane Pirika Takuup Dilini Ingilep Kiya Tipinini Koemale Ayene Sindawna Taronga Kasap Luth. Yaparep -

Estimating Adult Mortality in Papua New Guinea, 2011 Urarang Kitur* , Tim Adair and Alan D

Kitur et al. Population Health Metrics (2019) 17:4 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-019-0184-x RESEARCH Open Access Estimating Adult Mortality in Papua New Guinea, 2011 Urarang Kitur* , Tim Adair and Alan D. Lopez Abstract Background: Mortality in Papua New Guinea (PNG) is poorly measured because routine reporting of deaths is incomplete and inaccurate. This study provides the first estimates in the academic literature of adult mortality (45q15) in PNG by province and sex. These results are compared to a Composite Index of provincial socio- economic factors and health access. Methods: Adult mortality estimates (45q15) by province and sex were derived using the orphanhood method from data reported in the 2000 and 2011 national censuses. Male adult mortality was adjusted based on the estimated incompleteness of mortality reporting. The Composite Index was developed using the mean of education, economic and health access indicators from various data sources. Results: Adult mortality for PNG in 2011 was estimated as 269 per 1000 for males and 237 for females. It ranged from 197 in Simbu to 356 in Sandaun province among men, and from 164 in Western Highlands to 326 in Gulf province among women. Provinces with a low Composite Index (Sandaun, Gulf, Enga and Southern Highlands) had comparatively high levels of adult mortality for both sexes, while provinces with a higher Composite Index (National Capital District and Manus) reported lower adult mortality. Conclusions: Adult mortality in PNG remains high compared with other developing countries. Provincial variations in mortality correlate with the Composite Index. Health and development policy in PNG needs to urgently address the main causes of persistent high premature adult mortality, particularly in less developed provinces. -

An Ichthyological Survey of the Sepik River, Papua New Guinea

Rec. West. Aust. Mus. Suppl. no. 34 An ichthyological survey of the Sepik River, Papua New Guinea Gerald R. Allen* and David Coatest Abstract A survey of the freshwater fishes of the Sepik River system of northern Papua New r Guinea was undertaken by the authors between 1978 and 1985 with the use of gill nets and rotenone, and also by monitoring catches at local villages and markets. We also include records of past expeditions, namely that of the Dutch naturalist Gjellerup in 1910 and the yacht Illyria in 1929. The total known freshwater fauna as reported herein consists of 57 species in 35 genera and 23 families. The fauna is typical of other sections of New Guinea and northern Australia in that it is dominated by catfishes (Ariidae and Plotosidae), rainbowfishes (Melanotaeniidae), gudgeons (Eleotrididae) and gobies (Gobiidae) which collectively comprise 57 percent of the total species. With the exception of 22 widely distributed species that are frequently estuarine dwellers and are confined to the lower Sepik, the fishes are strongly endemic, either to the Sepik-Ramu drainages (which interconnect during floods), or the "intermontane trough" composed of the combined Markham, Ramu, Sepik, and Mamberamo systems. Individual accounts, including brief descriptions and information pertaining to habitat, distribution and biology are included for each species. In addition illustrations are provided for many of the endemic species. Introduction Considering its size, high rainfall and consequent abundance of fresh water habitats, the inland fishes of New Guinea (the term New Guinea is used in this paper to refer to the geographic unit composed of Papua New Guinea and Irian ]aya) are poorly documented except for scattered localities and a more or less comprehensive treatment of melanotaeniid rainbowfishes (AlIen and Cross 1982). -

National Fishery Sector Overview Papua New Guinea

FISHERY AND AQUACULTURE COUNTRY Food and Agriculture Organization of PROFILE the United Nations FID/CP/PNG PROFIL DE LA PÊCHE ET DE Organisation des Nations Unies pour L’AQUACULTURE PAR PAYS l'alimentation et l'agriculture RESUMEN INFORMATIVO SOBRE LA Organización de las Naciones Unidas PESCA Y LA ACUICULTURA POR PAÍSES para la Agricultura y la Alimentación January 2010 NATIONAL FISHERY SECTOR OVERVIEW PAPUA NEW GUINEA (PNG) 1. GENERAL GEOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC DATA Area: 462 243 sq km Water area: 3 120 000 sq km Shelf area: [not determined] Length of continental coastline: 17 000 km Population (2007)*: 6 423 000 GDP at purchaser's value (2005/06 financial year) 5 521 million USD1 GDP per head (2006): 891 USD Agricultural GDP (2006): 1 740 million USD2 Fisheries GDP (2006): 185 million USD3 *UN Population Division 2. FISHERIES DATA Total Per Caput 2007 Production Imports Exports Supply Supply tonnes liveweight kg/year Fish for direct human 228 458 28 355 143 207 113 606 17.7 consumption4 Fish for animal feed and other 35 502 --- --- --- purposes Estimated Employment: (i) Primary sector (including aquaculture): unavailable5 (ii) Secondary sector: Unavailable Gross value of fisheries output (2007): 812 millions USD6 1 Staff of the PNG National Statistics Office provided information on GDP (K.Geberi, personal comm., September 2008). The average PNG Kina to USD exchange rate in 2006 was 3.06. 2 Includes agriculture, forestry, and fishing 3 This is the official fishing contribution to GDP. A recalculation shows it to be about 15% greater. Source: Gillett, R. (2009). The Contribution of Fisheries to the Economies of Pacific Island Countries and Territories. -

O I L S E a R C H L I M I T E D Oil Search Profile

O I L S E A R C H L I M I T E D 1 Oil Search Profile Established in Papua New Guinea (PNG) in 1929 Market capitalisation ~US$11bn Listed on ASX (Share Code OSH) and POMSOX, plus ADR programme (Share Code OISHY) Tunis Sulaymaniyah Tunisia Operates all PNG’s currently Iraq Dubai producing oil and gas fields Sana’a Yemen PNG Government is largest shareholder with 15%. Exchangeable bond over shares Papua New Guinea Kutubu Ridge Camp issued to IPIC of Abu Dhabi Port Moresby (Head Office) 29% interest in PNG LNG Project, world scale LNG project operated Australia Brisbane by ExxonMobil Sydney Exploration interests in PNG, Middle East/North Africa 2 The Next Transformation PNG LNG being delivered progressively and predictably – four fold increase in production with similar impact on cash flows Focus on LNG expansion: OSH a major resource and infrastructure owner Optimal development of additional trains a major objective, resource understanding paramount Attractive economics – class-leading returns Continued PNG oil upside: Mananda Ridge a new focus Solid production from existing base Significant resource confirmed at Taza in Kurdistan: Moving to appraisal and staged development Balance sheet remains solid: Able to support unprecedented growth opportunities 3 Consistent strategy and disciplined capital management deliver share price growth A$ billion OSH Market Capitalisation & Share Price History A$/share 12 9.00 • Significant share price growth (23 Oct 13) o 20 years to date 959% 8.00 o 10 years to date 764% P’nyang South 10 discovery o 3 -

Sediment Transport in Distributary Channels and Its Export to the Pro-Deltaic Environment in a Tidally Dominated Delta: Fly River, Papua New Guinea

ARTICLE IN PRESS Continental Shelf Research 24 (2004) 2431–2454 www.elsevier.com/locate/csr Sediment transport in distributary channels and its export to the pro-deltaic environment in a tidally dominated delta: Fly River, Papua New Guinea Peter T. Harrisa,Ã, Michael G. Hughesb, Elaine K. Bakerb, Robert W. Dalrymplec, Jock B. Keeneb aMarine and Coastal Environment Group Geoscience Australia, GPO Box 378, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia bSchool of Geosciences, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia cDepartment of Geological Sciences and Geological Engineering, Queens University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada K7L 3N6 Available online 11 November 2004 Abstract Current metre deployments, suspended sediment measurements and surface sediment samples were collected from three locations within distributary channels of the tidally dominated Fly River delta in southern Papua New Guinea. Net bedload transport vectors and the occurrence of elongate tidal bars indicate that mutually evasive ebb-and flood- dominant transport zones occur in each of the distributary channels. Suspended sediment experiments at two locations show a phase relationship between tidal velocity and sediment concentration such that the net suspended sediment flux is directed seaward. Processes that control the export of fluid muds with concentrations up to 10 g lÀ1 from the distributary channels across the delta front and onto the pro-delta are assessed in relation to the available data. Peak spring tidal current speeds (measured at 100 cm above the bed) drop off from around 100 cm sÀ1 within the distributary channels to o50 cm sÀ1 on the delta front. Gravity-driven, 2-m thick, fluid mud layers generated in the distributary channels are estimated to require at least 35 h to traverse the 20-km-wide, low-gradient (2 Â 10À3 degrees) delta front.