A Becoming-Infinite-Cycle in Anne Boyd's Music: a Feminist-Deleuzian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Gamelan Manual: a Players Guide to the Central Javanese Gamelan Pdf

FREE A GAMELAN MANUAL: A PLAYERS GUIDE TO THE CENTRAL JAVANESE GAMELAN PDF Richard Pickvance | 336 pages | 30 Mar 2006 | Jaman Mas Books | 9780955029509 | English | London, United Kingdom - Wikipedia The music of Indonesia is regarded as relatively obscure to the Western listener, distant in geography but also in musical and cultural aesthetics. Despite this, gamelanwhich refers to various types of Indonesian orchestra and the different traditions and genres that such orchestras perform, has become increasingly prevalent in World Music circuits. While incomprehension sometimes relegates its overwhelming complexities and intricacies to Orientalist exoticism, gamelan offers a rare projection of Indonesian culture that has been revered and respected far beyond the edges of the archipelago. Situated in the Indian and Pacific oceans, the archipelago of Indonesia is the largest country in Southeast Asia and the most extensive island complex in the world, comprising more than 15, islands that are home to more than million people. Indonesia is a very diverse society, having provided a passageway for peoples and cultures between Oceania and mainland Asia for millennia. Ancient Indonesia was characterised by small estuary kingdoms. As no single hegemonic power emerged, the early history of Indonesia is the development of distinct regions that only gradually threaded together. Sailors from the archipelago became pioneering maritime explorers and merchants, establishing trade routes with places as far off as southern China and the east coast of Africa even in ancient times. Hinduism, brought to Indonesia by Brahmans from India c. However, as the Srivijaya kingdom on Sumatra expanded its maritime influence and made firm commercial links with China and India, it also spread Buddhism into parts of Indonesia 7 th th Cpromoting a social structure in which leaders bore the responsibility of ensuring that all had the means of ascetic worship through religious A Gamelan Manual: A Players Guide to the Central Javanese Gamelan and community rituals. -

The Consul Always Is, Always Was, and Always Will Be Aboriginal Land

To this we’ve come, that men withhold the world from men ... The Cooperative presents We perform today on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. We offer our utmost respect to the custodians of this land, their Elders past and present, and acknowledge that this The Consul always is, always was, and always will be Aboriginal Land. Sovereignty was never ceded. Words and music by Gian Carlo Menotti About The Cooperative The Cooperative is a brand new Sydney opera company with a passion for social justice. Our mission is four-fold: The Consul To provide performance opportunities for young and emerging artists To perform politically and/or socially relevant productions To increase opera’s accessibility; and, Musical Drama in Three Acts To use opera to benefit the world around us. Our auditions are open to all, and our cast comprised of experienced and Words and music by young artists, those well versed in opera, and those experienced in other art forms but making their operatic debut here. All our performances aim to remove the financial barriers of opera, with entry on a pay-as-you-feel Gian Carlo Menotti scale, and all our profits taken at the door go to a charity or charities connected to the ideas we’ve explored onstage. We believe that theatre has a unique power to illumine, explore, and challenge injustices within our society in a public dreaming. We have the privilege of performing an incredibly beautiful art form, and it is our duty to use that privilege for the benefit of our global society. -

Scales by Andy Csillag

17 Frets Scales By Andy Csillag https://drew.thecsillags.com/17frets Copyright © 2016 Andrew T. Csillag This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Introduction I’ve been playing guitar since I was in my teenage years, and I learned the diatonic and pentatonic scales mostly so I could improvise solos over rock music. While reading bits in Guitar magazine, where they would dissect a solo by some artist or other, I would note terms like Lydian and Mixolydian, and so on, but never really understood, since as far as my ear was concerned, they were just playing the normal scale just in a different key than whatever the rest of the tune was in, but since I mostly went by tablature, I was mostly ignorant of the main key, lacking the theoretical basis for what chords belong in what scales and so forth. For what it’s worth, I continued in my awareness but ignorance of modes well into my 30’s and early 40’s. Fast forward a bit, and I started learning how to improvise with Jazz, and the literature I was finding was treating things like D Dorian and B Locrian as it was a totally different thing than the normal C major scale. While they’re not the same in a theoretical sense, from a practical matter of what notes are in the scale, they’re exactly the same. -

Musical Scales and Multiplicative Groups

Bridges 2018 Conference Proceedings Musical Scales and Multiplicative Groups Donald Spector Dept. of Physics, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva, NY, USA; [email protected] Abstract Composers frequently apply mathematical operations to musical scales that treat a scale’s sequence of notes in additive fashion. Here, we introduce operations from multiplicative group theory to develop new methods of obtaining and transforming musical expressions. The methods are applicable to conventional and non-conventional scales. Introduction It is well known that standard musical scales have a mathematical underpinning. In Western music, just intonation is formed by identifying frequencies in certain whole number ratios with particular musical intervals, while well-tempered scales are obtained by having successive notes have a frequency ratio of 21/12, with octaves corresponding to a doubling of frequencies [4]. There are, of course, also microtonal [5] and non-octave scales [7]. In many contexts, however, it is customary to think of musical notes as forming an arithmetic sequence. Mathematically, one can think of this as labeling notes in terms of the logarithm of their frequencies, although that is not necessary for this paper. In the standard Western well-tempered chromatic scale, each octave consists of twelve notes, and, for example, transposing up a minor third means shifting every note three places in the scale. In this context, one typically treats the notes being defined using modular arithmetic, since that moving twelve halftones higher returns one to the same note, albeit shifted by an octave. In this paper, we introduce some methods for using instead multiplicative groups associated with modular arithmetic as a tool for music composition. -

Landscape, Spirit and Music: an Australian Story

Landscape, Spirit and Music: an Australian Story ANNE Boyo* (An accompanying compact disc holds the available music examples played. Their place is indicated by boxes in the text.) We belong to the ground It is our power And we must stay close to it Or maybe we will get lost. Narritjin Maymuru Yirrkala, an Australian Aborigine The earth is at the same time mother. She is mother of all that is natural, mother of all that is human. She is the mother of all, for contained in her are the seeds of all. Hildegard of Bingen1 The main language in Australia', David Tacey writes, 'is earth language: walking over the body of the earth, touching nature, feeling its presence and its other life, and attuning ourselves to its sensual reality'.2 If Tacey's view might be taken to embrace all the inhabitants from diverse cultural backgrounds now living in this ancient continent, then the language that connects us is what he calls 'earth language'. Earth language is a meta-language of the spirit which arises as right-brain activity based upon an intuitive connection with our natural environment, the language of place. Earth language has little to do with the left-brain language of human intellectual discourse. It is the territory of the sacred, long known to artists and deeply intuitive creative thinkers from all cultures through all time. It is the territory put off-limits by the * Anne Boyd holds the Chair of Music at the University of Sydney. This professorial lecture was delivered to the Arts Association on 16 May 2002. -

Final Thesis

Appendix – Compositions included in this study Date of Title Composer Ensemble Type Instrumentation Composition 1/01/1972322 Doubles for Wind Quartet Colin Brumby Quartet Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Bassoon 1/01/1972 Pas De deux Malcolm Williamson Duo Clarinet, Piano 2/10/1972 Divertimento Raymond Hanson Wind Quintet Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Alto Saxophone, Bassoon Horn 1/01/1973 Carrion Comfort Felix Werder Septet Voice (Treble), Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, French Horn, Percussion, Piano 1/01/1973 Chromatalea Haydn Reeder Quartet Flute/ Alto Flute, Clarinet (A)/ Bass Clarinet, Violin/ Viola, Violoncello 1/01/1973 Concert music for five solo Felix Werder Wind Quintet Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Bassoon, French Horn instruments, op.60 1/01/1973 Portraits of my friends and others Eric Austin-Phillips Quintet Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Bassoon, Piano 322 Works where only the year of composition has been able to be determined have been given the default date of 01/01/YEAR. The date of composition has been left blank for works that have been unable to be definitively dated at this time. 1/01/1973 Recollections of a Latvian song Ann Ghandar Quartet Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Piano 1/01/1973 Scherzo Felix Gethen Trio Oboe (or Flute or Violin), Clarinet, Bassoon (or Violoncello) 1/01/1973 Waltz: three instruments in and out Richard Peter Maddox Trio Flute, Oboe, Clarinet of three-quarter time 1/05/1973 Shadows Theodore Dollarhide Wind Quintet Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Bassoon, French Horn 20/06/1973 5 inventions Frederick Hill Duo Clarinet, Clarinet/ Bass Clarinet 4/09/1973 -

Our God Goes with Us Asian Heritage Month Worship Our Asian Heritage Month Worship Service This Year Focuses on the United Churches of Japanese-Canadian Background

Our God Goes with Us Asian Heritage Month Worship Our Asian Heritage Month worship service this year focuses on the United Churches of Japanese-Canadian background. These churches have had a rich though sometimes troubled journey. This service was written by David Kai, a third-generation Canadian of Japanese descent (Sansei) who grew up attending the Toronto Japanese United Church. Attached Resources • Scales sheet: Major scale, Pentatonic scale, Hirajoshi mode scale • Hymn: “Our God Goes with Us” I give permission for people to copy and use the music and just ask that your community of faith report the use to One License or CCLI. • Photo: Powell Street United Church Other Resources • “East of the Rockies” National Film Board app simulates the conditions of internment: www.nfb.ca/interactive/east_of_the_rockies/ • “A Ghost Town Tour” video presentation: https://youtu.be/rabJPKuXazA We Gather to Worship Acknowledgement of the Land As we gather here today on the traditional land of the people, we remember their stewardship of the land and their willingness to live in harmony with their neighbours. We remember also the pain of stolen land, broken promises, and forgotten treaties. As we gather here today, we remember also those who came to this land from around the world, some seeking opportunity, some seeking safety and asylum, some brought against their will. We celebrate all who came to make Canada their home, but we remember that all were not given equal welcome or equal treatment in this land. Today on this Sunday when we celebrate Asian Heritage Month, we remember in particular the story of Canadian Christians of Japanese heritage who have their own unique part in this country’s history and in The United Church of Canada. -

Australian Chamber Music with Piano

Australian Chamber Music with Piano Australian Chamber Music with Piano Larry Sitsky THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Sitsky, Larry, 1934- Title: Australian chamber music with piano / Larry Sitsky. ISBN: 9781921862403 (pbk.) 9781921862410 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Chamber music--Australia--History and criticism. Dewey Number: 785.700924 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Cover image: ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Preface . ix Part 1: The First Generation 1 . Composers of Their Time: Early modernists and neo-classicists . 3 2 . Composers Looking Back: Late romantics and the nineteenth-century legacy . 21 3 . Phyllis Campbell (1891–1974) . 45 Fiona Fraser Part 2: The Second Generation 4 . Post–1945 Modernism Arrives in Australia . 55 5 . Retrospective Composers . 101 6 . Pluralism . 123 7 . Sitsky’s Chamber Music . 137 Edward Neeman Part 3: The Third Generation 8 . The Next Wave of Modernism . 161 9 . Maximalism . 183 10 . Pluralism . 187 Part 4: The Fourth Generation 11 . The Fourth Generation . 225 Concluding Remarks . 251 Appendix . 255 v Acknowledgments Many thanks are due to the following. -

Native American Flute Meditation: Musical Instrument Design

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2008 Native American Flute Meditation: Musical Instrument Design, Construction and Playing as Contemplative Practice Daniel Cummings University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Mental and Social Health Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Daniel, "Native American Flute Meditation: Musical Instrument Design, Construction and Playing as Contemplative Practice" (2008). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 104. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/104http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/104 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Native American Flute Meditation: musical instrument design, construction and playing as contemplative practice by Dan Cummings © 2008 1 Introduction The two images on the preceding cover page represent the two traditions which have most significantly informed and inspired my personal flute journey, each in its own way contributing to an ongoing exploration of the design, construction and playing of Native American style flutes, as complementary aspects of a musically-oriented meditation practice. The first image is a typical artist’s rendition of Kokopelli, the flute-playing fertility deity who originated in the art and folklore of several Native North American cultures, particularly in the Southwestern region of the United States. Said to be representative of the spirit of music, today Kokopelli has become a ubiquitous symbol and quickly recognizable commercial icon associated with the Native American flute, or Native music and culture in general. -

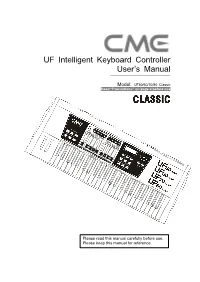

UF Intelligent Keyboard Controller User's Manual

UF Intelligent Keyboard Controller User’s Manual ————————————————— Model: UF50/60/70/80 Classic Read “Precautions” on page 4 before use Please read this manual carefully before use. Please keep this manual for reference. Thank you for choosing CME UF50/60/70/80 Classic Intelligent Keyboard Controller Please keep all the important information here Attach your invoice or receipt here ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ for reference Purchase date Serial(on the back of the keyboard) Dealer’s name and addr. Dealer’s tel. Warning: z Improper connection may cause damage to the device. Copyright z Copyright of the manual belongs to Central Music Co. Anyone must get a written permission from Central Music Co. before copying any part of the manual to any kind of media. © Central Music Co. 2009 Package list Please check all the items in the product package: z USB MIDI Master keyboard 1 pcs z USB Cable 1 pcs z User’s Manual 1 pcs 1 Special Message Section This product utilizes batteries or an external NOTICE: power supply (adapter). Do NOT connect this product to any power supply or adapter other Service charges incurred due to a lack of than one described in the manual, on the knowledge relating to how a function or effect product, or specifically recommended by CME. works (when the unit is operating as designed) are not covered by the manufacturer’s WARNING: Do not place this product in a warranty, and are therefore the owners position where anyone could walk on, trip over, responsibility. Please study this manual or roll anything over power or connecting cords carefully and consult your dealer before of any kind. -

A Becoming-Infinite-Cycle in Anne Boyd's Music

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242280975 A Becoming-Infinite-Cycle in Anne Boyd's Music: A Feminist-Deleuzian Exploration1 Article CITATIONS READS 0 95 1 author: Sally Macarthur Western Sydney University 27 PUBLICATIONS 108 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: International Study of Women Composers View project All content following this page was uploaded by Sally Macarthur on 23 September 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Volume 3 (2008) ISSN 1751-7788 A Becoming-Infinite-Cycle in Anne Boyd’s Music: A Feminist-Deleuzian Exploration1 Sally Macarthur University of Western Sydney The last two decades of the twentieth century witnessed the remarkable 1 transformation of musicology by feminist scholarship in its illumination of the music of previously forgotten women composers. By the turn of the twenty- first century, however, this scholarship had become merely a phenomenon of the 1990s.2 Women’s music, once again, has virtually disappeared from musicology in the Northern hemisphere,3 a finding which is echoed in Australia.4 A recent study paints a bleak picture, suggesting that women’s music is significantly under-represented in the theoretical studies of Australian tertiary music institutions.5 Music analysis, the staple diet of curricula in the vast majority of tertiary 2 music institutions, has contributed to this lop-sided view of music.6 While the discipline may appear to employ a broad range of theoretical models for studying Western art music,7 it does not correspondingly study a broad range of music. -

Paul Stanhope: Sydneychamberchoir.Org a New Requiem

Paul Stanhope: sydneychamberchoir.org A New Requiem Saturday 13 March | 7.30pm City Recital Hall Presented by City Recital Hall cityrecitalhall.com and Sydney Chamber Choir Saturday 13 March 2021 at 7.30pm City Recital Hall, Sydney Paul Stanhope: A New Requiem Sydney Chamber Choir Chloe Lankshear soprano Richard Butler tenor Callum Hogan oboe / cor anglais (Sydney Symphony Fellow) Richard Shaw clarinet / bass clarinet (Sydney Symphony Fellow) Jordy Meulenbroeks bassoon (Sydney Symphony Fellow) Euan Harvey horn (Sydney Symphony Orchestra) Emily Granger harp Jess Ciampa percussion Paul Stanhope conductor Presented by City Recital Hall and Sydney Chamber Choir. This concert is being recorded by ABC Classic for future broadcast. As a mark of respect to this wonderful music, Sydney Chamber Choir would appreciate it if audience members would turn off all sound- emitting devices. Thank you. 1 Sydney Chamber Choir on CD Lux Aeterna Choral works by Paul Stanhope, including Agnus Dei (Do not stand at my grave and weep) and Exile Lamentations Osanna New sacred works by Australian composer Clare Maclean Songs for the Shadowland Choral works by Paul Stanhope, including Geography Songs Francisco Guerrero Missa Surge propera and motets, performed under the direction of Michael Noone, accompanied by the Orchestra of the Renaissance on period instruments Landscape’s Creatures Music by Australian composers Stephen Adams, Raffæle Marcellino, Nicholas Routley and Paul Stanhope Clare Maclean: Choral Music Six early works by Australian composer Clare Maclean