A Media Content Analysis of Grizzly Bear Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RE-LAW LLP 4949 Bathurst Street, Suite 206 Toronto, Ontario M2R 1Y1 T

Aaron Rosenberg Email: [email protected] Direct Line: 416.789.4984 Fax: 416.429.2016 www.relawllp.ca Delivered by: E-mail File No.: 378.00018 July 28, 2020 Tyler Dawson, President Alberta Legislature Press Gallery Association [email protected] Katherine Kay Stikeman Elliott LLP 5300 Commerce Court West 199 Bay Street Toronto, Ontario M5L 1B9 [email protected] Dear Ms. Kay and Mr. Dawson: Re: Anti-Competitive Conduct by Postmedia Network Inc. (“Postmedia”) and the Alberta Legislature Press Gallery Association (“ALPGA”) I am writing on behalf of our clients, Sheila Gunn Reid, Keean Bexte, and Rebel News Network Ltd. (“Rebel News”). Please direct all future correspondence to the undersigned. We understand that our clients applied for membership with the ALPGA, and on July 27, 2020, as newly-elected president of the ALPGA, Mr. Dawson communicated its denial to Rebel News as follows (the “Denial”): Good morning, I have been elected as president of the Alberta Legislature Press Gallery Association as of our annual general meeting this morning. I'm writing to inform you that the gallery has voted to reject the applications of Sheila Gunn Reid and Keean Bexte of the Rebel News Network Ltd. for membership to the Alberta Legislature Press Gallery Association. Take care, Tyler Dawson — Tyler Dawson RE-LAW LLP 4949 Bathurst Street, Suite 206 Toronto, Ontario M2R 1Y1 T. 416.840.7316 Fax. 416.429.2016 2 Alberta correspondent National Post [email protected] The Denial was communicated without reasons — the only stated reason for this decision is that the ALPGA “voted to reject the applications”. -

ALBERTA ENVIRONMENTAL APPEAL BOARD Decision

Appeal Nos. 01-106 and 108-D ALBERTA ENVIRONMENTAL APPEAL BOARD Decision Date of Decision – June 15, 2002 IN THE MATTER OF sections 91, 92, and 95 of the Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act, R.S.A. 2000, c. E-12; -and- IN THE MATTER OF appeals filed by Mr. Andy Dzurny and Mr. William Procyk with respect to Amending Approval No. 9767-01-09 issued on October 26, 2001, by the Director, Northeast Boreal Region, Regional Services, Alberta Environment, to Shell Chemicals Canada Ltd. Cite as: Dzurny et al. v. Director, Northeast Boreal Region, Regional Services, Alberta Environment re: Shell Chemicals Canada Ltd. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Board received Notices of Appeal from Mr. Andy Dzurny and Mr. William Procyk with respect to an amending approval issued by Alberta Environment to Shell Chemicals Canada Ltd. with respect to the operation of the Scotford Chemical Plant in Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta. According to standard practice, the Board wrote to the Alberta Energy and Utilities Board (AEUB) asking whether the matters included in these Notices of Appeal had been the subject of a review or hearing under the AEUB’s legislation. The AEUB advised the Board that it had held a hearing in relation to the Shell Scotford Chemical Plant. In response to this, the Board asked for submissions from Mr. Dzurny, Mr. Procyk, Shell Canada, and Alberta Environment as to whether the matters included in the Notices of Appeal had been the subject of a review or hearing under the AEUB’s legislation. Upon reviewing the documents provided by the AEUB and the submissions from the Parties to these appeals, the Board has concluded that the matters included in the Notices of Appeal were previously dealt with by the AEUB. -

Newspaper Topline Readership - Monday-Friday Vividata Summer 2018 Adults 18+

Newspaper Topline Readership - Monday-Friday Vividata Summer 2018 Adults 18+ Average Weekday Audience 18+ (Mon - Fri) (000) Average Weekday Audience 18+ (Mon - Fri) (000) Title Footprint (1) Print (2) Digital (3) Footprint (1) Print (2) Digital (3) NATIONAL WINNIPEG CMA The Globe and Mail 2096 897 1544 The Winnipeg Sun 108 79 46 National Post 1412 581 1022 Winnipeg Free Press 224 179 94 PROVINCE OF ONTARIO QUÉBEC CITY CMA The Toronto Sun 664 481 317 Le Journal de Québec 237 170 100 Toronto Star 1627 921 957 Le Soleil 132 91 65 PROVINCE OF QUÉBEC HAMILTON CMA La Pressea - - 1201 The Hamilton Spectator 232 183 91 Le Devoir 312 149 214 LONDON CMA Le Journal de Montréal 1228 868 580 London Free Press 147 87 76 Le Journal de Québec 633 433 286 KITCHENER CMA Le Soleil 298 200 146 Waterloo Region Record 133 100 41 TORONTO CMA HALIFAX CMA Metro/StarMetro Toronto 628 570 133 Metro/StarMetro Halifax 146 116 54 National Post 386 174 288 The Chronicle Herald 122 82 61 The Globe and Mail 597 308 407 ST. CATHARINES/NIAGARA CMA The Toronto Sun 484 370 215 Niagara Falls Review 48 34 21* Toronto Star 1132 709 623 The Standard 65 39 37 MONTRÉAL CMA The Tribune 37 21 23 24 Heures 355 329 60 VICTORIA CMA La Pressea - - 655 Times Colonist 119 95 36 Le Devoir 185 101 115 WINDSOR CMA Le Journal de Montréal 688 482 339 The Windsor Star 148 89 83 Métro 393 359 106 SASKATOON CMA Montréal Gazette 166 119 75 The StarPhoenix 105 61 59 National Post 68 37 44 REGINA CMA The Globe and Mail 90 46 56 Leader Post 82 48 44 VANCOUVER CMA ST.JOHN'S CMA Metro/StarMetro Vancouver -

International Press Clippings Report

INTERNATIONAL PRESS CLIPPINGS REPORT July, 2020 OUTLET KEY MESSAGING MARKET DATE UMV CIRCULATION AD VALUE/ EAV (USD) Discover Puerto Rico prepares to attract El Nuevodia Colombia 01/07 375,000 tourists and the diaspora Top alfresco dining NI Travel News experiences from UK 01/07 202,042 526 around the world How to make a Pina Yahoo! Colada at home, UK 03/07 43,100,000 1,300 according to the hotel bar that invented it The best sports around the world where you can Tempus Magazine UK 03/07 12,493 1,200 now indulge in al fresco dining Puerto Rico plans to MSN reopen to travellers on UK 03/07 23,000,000 1,220 July 15 Puerto Rico travel restrictions: Island Travel Pule Canada 03/07 166,315 1,462 outlines plan to reopen tourism on July 15 OUTLET KEY MESSAGING MARKET DATE UMV CIRCULATION AD VALUE/ EAV (USD) Best golf courses to Affinity Magazine UK 10/07 25,000 1,040 enjoy around the world The best Caribbean islands reopening to UK Telegraph Online tourists - our expert’s UK 22/07 24,886,000 4,506 guide on where to stay during coronavirus Events: The Luxe List Luxe Bible UK 20/07 4,100 132 July 2020 Let’s celebrate the festive holidays at the Ottowa Sun Canada 24/07 175,000 1,462 halfway mark Let’s celebrate the festive holidays at the County Market Canada 24/07 500 180 halfway mark Let’s celebrate the festive holidays at the Sudbury Star Canada 24/07 75,000 655 halfway mark OUTLET KEY MESSAGING MARKET DATE UMV CIRCULATION AD VALUE/ EAV (USD) Let’s celebrate the festive holidays at the The delhi News Record Canada 24/07 500 180 halfway mark Let’s -

Overview of Results: Fall 2020 Study STUDY SCOPE – Fall 2020 10 Provinces / 5 Regions / 40 Markets • 32,738 Canadians Aged 14+ • 31,558 Canadians Aged 18+

Overview of Results: Fall 2020 Study STUDY SCOPE – Fall 2020 10 Provinces / 5 Regions / 40 Markets • 32,738 Canadians aged 14+ • 31,558 Canadians aged 18+ # Market Smpl # Market Smpl # Market Smpl # Provinces 1 Toronto (MM) 3936 17 Regina (MM) 524 33 Sault Ste. Marie (LM) 211 1 Alberta 2 Montreal (MM) 3754 18 Sherbrooke (MM) 225 34 Charlottetown (LM) 231 2 British Columbia 3 Vancouver (MM) 3016 19 St. John's (MM) 312 35 North Bay (LM) 223 3 Manitoba 4 Calgary (MM) 902 20 Kingston (LM) 282 36 Cornwall (LM) 227 4 New Brunswick 5 Edmonton (MM) 874 21 Sudbury (LM) 276 37 Brandon (LM) 222 5 Newfoundland and Labrador 6 Ottawa/Gatineau (MM) 1134 22 Trois-Rivières (MM) 202 38 Timmins (LM) 200 6 Nova Scotia 7 Quebec City (MM) 552 23 Saguenay (MM) 217 39 Owen Sound (LM) 200 7 Ontario 8 Winnipeg (MM) 672 24 Brantford (LM) 282 40 Summerside (LM) 217 8 Prince Edward Island 9 Hamilton (MM) 503 25 Saint John (LM) 279 9 Quebec 10 Kitchener (MM) 465 26 Peterborough (LM) 280 10 Saskatchewan 11 London (MM) 384 27 Chatham (LM) 236 12 Halifax (MM) 457 28 Cape Breton (LM) 269 # Regions 13 St. Catharines/Niagara (MM) 601 29 Belleville (LM) 270 1 Atlantic 14 Victoria (MM) 533 30 Sarnia (LM) 225 2 British Columbia 15 Windsor (MM) 543 31 Prince George (LM) 213 3 Ontario 16 Saskatoon (MM) 511 32 Granby (LM) 219 4 Prairies 5 Quebec (MM) = Major Markets (LM) = Local Markets Source: Vividata Fall 2020 Study 2 Base: Respondents aged 18+. -

2021 Ownership Groups - Canadian Daily Newspapers (74 Papers)

2021 Ownership Groups - Canadian Daily Newspapers (74 papers) ALTA Newspaper Group/Glacier (3) CN2i (6) Independent (6) Quebecor (2) Lethbridge Herald # Le Nouvelliste, Trois-Rivieres^^ Prince Albert Daily Herald Le Journal de Montréal # Medicine Hat News # La Tribune, Sherbrooke^^ Epoch Times, Vancouver Le Journal de Québec # The Record, Sherbrooke La Voix de l’Est, Granby^^ Epoch Times, Toronto Le Soleil, Quebec^^ Le Devoir, Montreal Black Press (2) Le Quotidien, Chicoutimi^^ La Presse, Montreal^ SaltWire Network Inc. (4) Red Deer Advocate Le Droit, Ottawa/Gatineau^^ L’Acadie Nouvelle, Caraquet Cape Breton Post # Vancouver Island Free Daily^ Chronicle-Herald, Halifax # The Telegram, St. John’s # Brunswick News Inc. (3) The Guardian, Charlottetown # Times & Transcript, Moncton # Postmedia Network Inc./Sun Media (33) The Daily Gleaner, Fredericton # National Post # The London Free Press Torstar Corp. (7) The Telegraph-Journal, Saint John # The Vancouver Sun # The North Bay Nugget Toronto Star # The Province, Vancouver # Ottawa Citizen # The Hamilton Spectator Continental Newspapers Canada Ltd.(3) Calgary Herald # The Ottawa Sun # Niagara Falls Review Penticton Herald The Calgary Sun # The Sun Times, Owen Sound The Peterborough Examiner The Daily Courier, Kelowna Edmonton Journal # St. Thomas Times-Journal St. Catharines Standard The Chronicle Journal, Thunder Bay The Edmonton Sun # The Observer, Sarnia The Tribune, Welland Daily Herald-Tribune, Grande Prairie The Sault Star, Sault Ste Marie The Record, Grand River Valley F.P. Canadian Newspapers LP (2) The Leader-Post, Regina # The Simcoe Reformer Winnipeg Free Press The StarPhoenix, Saskatoon # Beacon-Herald, Stratford TransMet (1) Brandon Sun Winnipeg Sun # The Sudbury Star Métro Montréal The Intelligencer, Belleville The Daily Press, Timmins Glacier Media (1) The Expositor, Brantford The Toronto Sun # Times Colonist, Victoria # The Brockville Recorder & Times The Windsor Star # The Chatham Daily News The Sentinel Review, Woodstock Globe and Mail Inc. -

Calgary Folk Club Media Contacts As of 9/3/09

Calgary Folk Club Media Contacts as of 9/3/09 Calgary Herald http://www.calgaryherald.com/ To submit events go to URL: http://www.newsdayinteractive.com/forms/2006/promote-events/index.php E-mail: [email protected] SWERVE: http://www2.canada.com/calgaryherald/news/swerve/index.html E-mail: [email protected] Fast Forward www.ffwdweekly.com free weekly news and comment Fast Forward Weekly, #206-1210 20 Avenue S.E., Calgary, Alberta, CANADA T2G 1M8. Peter Hemminger - Music and Film Editor 403-244-2235 ext. 28, [email protected]. Kari Watson - Listings Editor, 403-244-2235, [email protected]. The CKUA Radio Network www.ckua.com Alberta public radio Tom Coxworth, Producer/Host, Folk Routes [email protected]. Andy Donnelly, Producer/Host, The Celtic Show [email protected]. The CKUA Arts and Culture Guide is heard twice daily, Monday through Saturday and is compiled by Chris Allen and Megan Karasek. If you have an arts or cultural event taking place in your area, email at least two weeks in advance at [email protected]. CBC Radio 1 1010 AM Calgary You have to use the online ‘contact’ links for each program to e-mail them. Calgary Eyeopener http://www.cbc.ca/eyeopener/contact.html#. Weekday mornings, host Jim Brown <http://www.cbc.ca/eyeopener/jimbrown.html>. Chris Dela Torre is The Eyeopener's Scenester; he broadcasts on Friday mornings. <http://www.cbc.ca/eyeopener/scenester.html>. Homestretch: http://www.cbc.ca/homestretch/contact.html#. Weekday Afternoons 3:00 to 6:00 p.m. Host David Gray. -

Daily Newspapers / 147 Dailydaily Newspapersnewspapers

Media Names & Numbers Daily Newspapers / 147 DailyDaily NewspapersNewspapers L’Acadie Nouvelle E-Mail: [email protected] Dave Naylor, City Editor Circulation: 20000 Larke Turnbull, City Editor Phone: 403-250-4122/124 CP 5536, 476, boul. St-Pierre Ouest, Phone: 519-271-2220 x203 E-Mail: [email protected] Caraquet, NB E1W 1K0 E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 506-727-4444 800-561-2255 Cape Breton Post FAX: 506-727-7620 The Brandon Sun Circulation: 28300 E-Mail: [email protected] Circulation: 14843, Frequency: Weekly P.O. Box 1500, 255 George St., WWW: www.acadienouvelle.com 501 Rosser Ave., Brandon, MB R7A 0K4 Sydney, NS B1P 6K6 Gaetan Chiasson, Directeur de l’information Phone: 204-727-2451 FAX: 204-725-0976 Phone: 902-564-5451 FAX: 902-564-6280 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] WWW: www.capebretonpost.com Bruno Godin, Rédacteur en Chef WWW: www.brandonsun.com E-Mail: [email protected] Craig Ellingson, City Editor Bonnie Boudreau, City Desk Editor Phone: 204-571-7430 Phone: 902-563-3839 FAX: 902-562-7077 Lorio Roy, Éditeur E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Jim Lewthwaite, News Editor Fred Jackson, Managing Editor Alaska Highway News Phone: 204-571-7433 Phone: 902-563-3843 Circulation: 3700 Gord Wright, Editor-in-Chief E-Mail: [email protected] 9916-98th St., Fort St. John, BC V1J 3T8 Phone: 204-571-7431 Chatham Daily News Phone: 250-785-5631 FAX: 250-785-3522 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Circulation: 15600 WWW: www.cna-acj.ca Brockville Recorder and Times P.O. -

Download Print on Demand Titles

Print–on–Demand There are over 2500 titles from over 100 countries in 60 languages available on our Print-on-Demand network. Titles by country Language Schedule Albania Gazeta Paloma ......................................................................................................... Albanian .............. - - - - - - S Gazeta Shqiptare ...................................................................................................... Albanian .............. S M T W T F S Koha Ditore ............................................................................................................... Albanian .............. S M T W T F S Shekulli ..................................................................................................................... Albanian .............. S M T W T F S Une Gruaja ............................................................................................................... Albanian .............. S - - - - - - Angola Folha 8 ...................................................................................................................... Portuguese ......... - - - - - - S Jornal de Angola ....................................................................................................... Portuguese ......... S M T W T F S Jornal dos Desportos ............................................................................................... Portuguese ......... S M T W T F S Argentina Caras ....................................................................................................................... -

News As Hazardous Waste: Postmedia, the Competition Bureau, and the Supreme Court of Canada

News as Hazardous Waste: Postmedia, the Competition Bureau, and the Supreme Court of Canada Marc Edge University of Malta & University Canada West ABSTRACT Background In early 2015, a few months after Postmedia Network, Canada’s largest news - paper company, purchased 175 Sun Media titles from Quebecor Inc., the Supreme Court of Canada rendered a landmark decision. It allowed the purchase of one hazardous waste com - pany by another because the Competition Bureau, which had blocked the deal, failed to quan - tify the anti-competitive effects of the monopoly created. Analysis The ruling set an important precedent for the Postmedia purchase, which was ap - proved by the Competition Bureau two months later. Conclusions and implications This article points up the problematic nature of competition cases involving news media companies and the need for reform of the Competition Act to prevent such cases from being decided solely on economic grounds, as now mandated by the Supreme Court. Keywords Newspapers; Postmedia; Competition Bureau; Press ownership concentration RÉSUMÉ Contexte Au début de 2015, quelques mois après que le plus grand groupe de presse au Canada, Postmedia Network, a acheté les 175 journaux Sun Media de Québecor Inc., la Cour suprême du Canada a pris une décision marquante. Elle a permis l’achat d’une compagnie de matières dangereuses par une autre parce que le Bureau de la concurrence, qui avait bloqué la transaction, avait échoué à quantifier les effets anticoncurrentiels du monopole qui s’ensuivrait. Analyse Cette décision a constitué un précédent important pour l’achat par Postmedia que le Bureau de la concurrence approuverait deux mois plus tard. -

Postmedia B No Emails.Csv

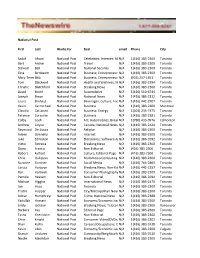

National Post First Last Works for Beat email Phone City Sadaf Ahsan National Post Celebrities; Internet; MotionN/A Pictures1(416) 383-2300 Toronto Bert Archer National Post Travel N/A 1(416) 383-2300 Toronto Stewart Bell National Post National Security N/A 1(416) 383-2300 Toronto Elisa Birnbaum National Post Business; Entrepreneurs;N/A Social Issues1(416) 383-2300 Toronto Mary TeresaBitti National Post Business; EntrepreneursN/A (905) 257-1651 Toronto Tom Blackwell National Post Health and Wellness; MedicalN/A 1(416) 383-2394 Toronto Christie Blatchford National Post Breaking News N/A 1(416) 383-2300 Toronto David Booth National Post Automobiles N/A 1(416) 510-6744 Toronto Joseph Brean National Post National News N/A 1(416) 383-2312 Toronto Laura Brehaut National Post Beverages; Culture; Food;N/A Internet;1(416) Recipes 442-2907 Toronto Kevin Carmichael National Post Business N/A 1(416) 383-2300 Montreal Claudia Cattaneo National Post Business; Energy N/A 1(403) 235-7375 Toronto Terence Corcoran National Post Business N/A 1(416) 383-2381 Toronto Colby Cosh National Post Art; Automobiles; BreakingN/A News;1(780) Culture; 433-0976 Economy/EconomicEdmonton Issues; Financial; Health and Wellness; Law; Medical; Meteorology; Sports Andrew Coyne National Post Canada; National News; N/APolitics 1(416) 383-2420 Toronto Raymond De Souza National Post Religion N/A 1(416) 383-2300 Toronto Aileen Donnelly National Post Internet N/A 1(416) 383-2300 Toronto Jake Edmiston National Post Electronics; Software ApplicationsN/A 1(416) 386-2692 Toronto Victor -

Decision 2006-085

Decision 2006-085 Shell Canada Limited Application to Expand the Scotford Upgrader Strathcona County, Fort Saskatchewan August 29, 2006 ALBERTA ENERGY AND UTILITIES BOARD Decision 2006-085: Shell Canada Limited, Application to Expand the Scotford Upgrader, Strathcona County, Fort Saskatchewan August 29, 2006 Published by Alberta Energy and Utilities Board 640 – 5 Avenue SW Calgary, Alberta T2P 3G4 Telephone: (403) 297-8311 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (403) 297-7040 Web site: www.eub.ca Application to Expand the Scotford Upgrader Shell Canada Limited CONTENTS 1 Decision .................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Application ....................................................................................................................... 1 2.2 Interventions..................................................................................................................... 1 2.3 Hearing ............................................................................................................................. 1 3 Background............................................................................................................................... 2 4 Issues........................................................................................................................................