A Return to 1987: Glenda Dickerson's Black Feminist Intervention” by Khalid Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AAS 310 BLACK WOMEN in the AMERICAS Spring 2016

AAS 310 BLACK WOMEN IN THE AMERICAS Spring 2016 Professor: Place: Day/Time: Office/ Office hours: Course Description: This course presents an interdisciplinary body of scholarship on the social, political, economic, cultural and historical contexts of Black women’s lives in the United States and across the Americas, with a particular focus on Black women’s roles in the development of democratic ideas. We will also focus on the relationship between representations and realities of Black women. One of the central questions we will ask is who constitutes as a black woman? Considering the experiences of mixed-race African American women, Black women in Latin America and the Caribbean, and queer Black women will allow us to consider the ways that race, gender, sexuality and nation operate. Course Objectives: 1. To examine the history, development and significance of Black Women's Studies as a discipline that evolved from the intersection of grassroots activism, "womanist" knowledge and the quest for human rights in a democracy. 2. To examine the terms “Feminist Theory”, “Black Feminist Theory” and “Womanist Theory” as conceptual frameworks for knowledge production about Black women’s lives. 3. To examine “intersectionality” as a critical factor in Black women’s lived experiences in America. 4. To critically analyze stereotypes and images of Black womanhood and the ideologies surrounding these images and to explore the social, political and policy implications of these images. 5. To introduce students to an interdisciplinary body of feminist research, critical essays, prose, fiction, poetry and films by and about Black American women. Student Learning Outcomes: 1. -

Special Issue 4 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571

BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science An Online, Peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal Vol: 2 Special Issue: 4 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571 UGC approved Journal (J. No. 44274) CENTRE FOR RESOURCE, RESEARCH & PUBLICATION SERVICES (CRRPS) www.crrps.in | www.bodhijournals.com BODHI BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science (ISSN: 2456-5571) is online, peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal, which is powered & published by Center for Resource, Research and Publication Services, (CRRPS) India. It is committed to bring together academicians, research scholars and students from all over the world who work professionally to upgrade status of academic career and society by their ideas and aims to promote interdisciplinary studies in the fields of humanities, arts and science. The journal welcomes publications of quality papers on research in humanities, arts, science. agriculture, anthropology, education, geography, advertising, botany, business studies, chemistry, commerce, computer science, communication studies, criminology, cross cultural studies, demography, development studies, geography, library science, methodology, management studies, earth sciences, economics, bioscience, entrepreneurship, fisheries, history, information science & technology, law, life sciences, logistics and performing arts (music, theatre & dance), religious studies, visual arts, women studies, physics, fine art, microbiology, physical education, public administration, philosophy, political sciences, psychology, population studies, social science, sociology, social welfare, linguistics, literature and so on. Research should be at the core and must be instrumental in generating a major interface with the academic world. It must provide a new theoretical frame work that enable reassessment and refinement of current practices and thinking. This may result in a fundamental discovery and an extension of the knowledge acquired. -

Black Feminist Thought by Patricia Hill Collins • Eloquent Rage: a Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower by Dr

Resource List Books to read: • Black Feminist Thought by Patricia Hill Collins • Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower by Dr. Brittney Cooper • Heavy: An American Memoir by Kiese Laymon • How To Be An Antiracist by Dr. Ibram X. Kendi • I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou • Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson • Me and White Supremacy by Layla F. Saad • Raising Our Hands by Jenna Arnold • Redefining Realness by Janet Mock • Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde • So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo • The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison • The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin • The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander • The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century by Grace Lee Boggs • The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson • Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston • This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color by Cherríe Moraga • When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth Century America by Ira Katznelson • White Fragility: Why It's So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Robin DiAngelo, PhD • Fania Davis' Little Book of Race and RJ • Danielle Sered's Until We Reckon • The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness Films and TV series to watch: • 13th (Ava DuVernay) — Netflix • American Son (Kenny Leon) — Netflix • Black Power Mixtape: 1967-1975 — Available to rent • Blindspotting (Carlos López Estrada) — Hulu with Cinemax or available to rent • Clemency (Chinonye Chukwu) — Available to rent • Dear White People (Justin Simien) — Netflix • Fruitvale Station (Ryan Coogler) — Available to rent • I Am Not Your Negro (James Baldwin doc) — Available to rent or on Kanopy • If Beale Street Could Talk (Barry Jenkins) — Hulu • Just Mercy (Destin Daniel Cretton) — Available to rent for free in June in the U.S. -

The Black Woman As Artist and Critic: Four Versions

The Kentucky Review Volume 7 | Number 1 Article 3 Spring 1987 The lB ack Woman As Artist and Critic: Four Versions Margaret B. McDowell University of Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation McDowell, Margaret B. (1987) "The lB ack Woman As Artist and Critic: Four Versions," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 7 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol7/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Black Woman As Artist and Critic: Four Versions 1ett Margaret B. McDowell ·e H. Telling stories and writing criticism, Eudora Welty says, are "indeed separate gifts, like spelling and playing the flute, and the same writer proficient in both has been doubly endowed, but even and he can't rise and do both at the same time."1 In view of the o: general validity of this observation, it is remarkable that several of the best Afro-American women authors are also invigorating Hill critics. City 6), Notable among them are Margaret Walker, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, and Toni Morrison. In the breadth of their inquiry, the ~ss, " zest of their argument, and the intensity of their commitment to issues related to art, race, and gender, they exemplify a new vitality that emerged after about 1970 in women's discourse about black literature. -

Here May Is Not Rap Be Music D in Almost Every Major Language,Excerpted Including Pages Mandarin

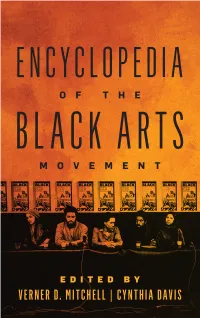

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT ed or printed. Edited by istribut Verner D. Mitchell Cynthia Davis an uncorrected page proof and may not be d Excerpted pages for advance review purposes only. All rights reserved. This is ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 18_985_Mitchell.indb 3 2/25/19 2:34 PM ed or printed. Published by Rowman & Littlefield An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 istribut www.rowman.com 6 Tinworth Street, London, SE11 5AL, United Kingdom Copyright © 2019 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Mitchell, Verner D., 1957– author. | Davis, Cynthia, 1946– author. Title: Encyclopedia of the Black Arts Movement / Verner D. Mitchell, Cynthia Davis. Description: Lanhaman : uncorrectedRowman & Littlefield, page proof [2019] and | Includes may not bibliographical be d references and index. Identifiers:Excerpted LCCN 2018053986pages for advance(print) | LCCN review 2018058007 purposes (ebook) only. | AllISBN rights reserved. 9781538101469This is (electronic) | ISBN 9781538101452 | ISBN 9781538101452 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Black Arts movement—Encyclopedias. Classification: LCC NX512.3.A35 (ebook) | LCC NX512.3.A35 M58 2019 (print) | DDC 700.89/96073—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018053986 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

Anthologies of African American Women's Writing And

Reading Democracy: Anthologies of African American Women’s Writing and the Legacy of Black Feminist Criticism, 1970-1990 by Aisha Peay Department of English Duke University Date: __________________ Approved: ______________________________ Priscilla Wald, Chair ______________________________ Thomas J. Ferraro ______________________________ Ranjana Khanna ______________________________ Kathy Psomiades Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT Reading Democracy: Anthologies of African American Women’s Writing and the Legacy of Black Feminist Criticism, 1970-1990 by Aisha Peay Department of English Duke University Date: __________________ Approved: ______________________________ Priscilla Wald, Chair ______________________________ Thomas J. Ferraro ______________________________ Ranjana Khanna ______________________________ Kathy Psomiades An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Aisha Peay 2009 ABSTRACT Taking as its pretext the contemporary moment of self-reflexive critique on the part of interdisciplinary programs like Women’s Studies and American Studies, Reading Democracy historicizes a black feminist literary critical practice and movement that developed alongside black feminist activism beginning in the 1970s. This dissertation -

Black Theatre Movement PREPRINT

PREPRINT - Olga Barrios, The Black Theatre Movement in the United States and in South Africa . Valencia: Universitat de València, 2008. 2008 1 To all African people and African descendants and their cultures for having brought enlightenment and inspiration into my life 3 CONTENTS Pág. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS …………………………………………………………… 6 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………….. 9 CHAPTER I From the 1950s through the 1980s: A Socio-Political and Historical Account of the United States/South Africa and the Black Theatre Movement…………………. 15 CHAPTER II The Black Theatre Movement: Aesthetics of Self-Affirmation ………………………. 47 CHAPTER III The Black Theatre Movement in the United States. Black Aesthetics: Amiri Baraka, Ed Bullins, and Douglas Turner Ward ………………………………. 73 CHAPTER IV The Black Theatre Movement in the United States. Black Women’s Aesthetics: Lorraine Hansberry, Adrienne Kennedy, and Ntozake Shange …………………….. 109 CHAPTER V The Black Theatre Movement in South Africa. Black Consciousness Aesthetics: Matsemala Manaka, Maishe Maponya, Percy Mtwa, Mbongeni Ngema and Barney Simon …………………………………... 144 CHAPTER VI The Black Theatre Movement in South Africa. Black South African Women’s Voices: Fatima Dike, Gcina Mhlophe and Other Voices ………………………………………. 173 CONCLUSION ………………………………………………………………………… 193 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………………………………………………… 199 APPENDIX I …………………………………………………………………………… 221 APPENDIX II ………………………………………………………………………….. 225 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Writing this book has been an immeasurable reward, in spite of the hard and critical moments found throughout its completion. The process of this culmination commenced in 1984 when I arrived in the United States to pursue a Masters Degree in African American Studies for which I wish to thank very sincerely the Fulbright Fellowships Committee. I wish to acknowledge the Phi Beta Kappa Award Selection Committee, whose contribution greatly helped solve my financial adversity in the completion of my work. -

Art for Women's Sake: Understanding Feminist Art Therapy As Didactic Practice Re-Orientation

© FoNS 2013 International Practice Development Journal 3 (Suppl) [5] http://www.fons.org/library/journal.aspx Art for women’s sake: Understanding feminist art therapy as didactic practice re-orientation *Toni Wright, Karen Wright *Corresponding author: Canterbury Christ Church University, Department of Nursing and Applied Clinical Studies, Canterbury, Kent, UK. Email: [email protected] Submitted for publication: 14th January 2013 Accepted for publication: 6th February 2013 Abstract Catalysed through the coming together of feminist theories that debate ‘the politics of difference’ and through a reflection on the practices of art psychotherapy, this paper seeks to illuminate the progressive and empowering nature that creative applications have for better mental health. It also seeks to critically expose and evaluate some of the marginalisation work that is also done within art psychotherapy practices, ultimately proposing a developmental practice activity and resource hub that will raise awareness, challenge traditional ways of thinking and doing, and provide a foundation for more inclusive practices. This paper’s introduction is followed by a contextualisation of art therapy and third wave feminisms, with suggestions of how those can work together towards better praxis. The main discussion is the presentation of a newly developed practitioner activity and resource hub that art therapists can use to evaluate their current and ongoing practice towards one of greater inclusivity and better reflexivity. Finally, in conclusion there will be a drawing together of what has been possible in feminist art psychotherapy, what remains possible, and with further alliances what more could yet be possible. A video that accompanies this paper is available from: www.youtube.com/watch?v=fLLXVGiZQcU. -

The Women of August Wilson and a Performance Study and Analysis of the Role of Grace in Wilson's the Piano Lesson

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2009 The Women Of August Wilson And A Performance Study And Analysis Of The Role Of Grace In Wilson's The Piano Lesson Ingrid Marable University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Marable, Ingrid, "The Women Of August Wilson And A Performance Study And Analysis Of The Role Of Grace In Wilson's The Piano Lesson" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4150. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4150 THE WOMEN OF AUGUST WILSON AND A PERFORMANCE STUDY AND ANALYSIS OF THE ROLE OF GRACE IN WILSON’S THE PIANO LESSON by INGRID A. MARABLE B.A. University of Virginia, 2005 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer 2009 © 2009 Ingrid A. Marable ii ABSTRACT In the fall of 2007, I was cast in the University of Central Florida’s production of The Piano Lesson. My thesis will examine my performance in the role of Grace, as well as understudying the role of Berniece under the direction of Professor Belinda Boyd. -

Black Feminist Thought

Praise for the first edition of Black Feminist Thought “The book argues convincingly that black feminists be given, in the words immor- talized by Aretha Franklin, a little more R-E-S-P-E-C-T....Those with an appetite for scholarese will find the book delicious.” —Black Enterprise “With the publication of Black Feminist Thought, black feminism has moved to a new level. Collins’ work sets a standard for the discussion of black women’s lives, experiences, and thought that demands rigorous attention to the complexity of these experiences and an exploration of a multiplicity of responses.” —Women’s Review of Books “Patricia Hill Collins’ new work [is] a marvelous and engaging account of the social construction of black feminist thought. Historically grounded, making excellent use of oral history, interviews, music, poetry, fiction, and scholarly literature, Hill pro- poses to illuminate black women’s standpoint. .Those already familiar with black women’s history and literature will find this book a rich and satisfying analysis. Those who are not well acquainted with this body of work will find Collins’ book an accessible and absorbing first encounter with excerpts from many works, inviting fuller engagement. As an overview, this book would make an excellent text in women’s studies, ethnic studies, and African-American studies courses, especially at the upper-division and graduate levels. As a meditation on the deeper implications of feminist epistemology and sociological practice, Patricia Hill Collins has given us a particular gift.” —Signs “Patricia Hill Collins has done the impossible. She has written a book on black feminist thought that combines the theory with the most immediate in feminist practice. -

Ahern Dissertation Final

Affect in Epistemology: Relationality and Feminist Agency in Critical Discourse, Neuroscience, and Novels by Bambara, Morrison, and Silko by Megan Keady Ahern A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English and Women’s Studies) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Awkward, Chair Associate Professor Tiya Miles Associate Professor Joshua L. Miller Assistant Professor Sari M. van Anders Professor Priscilla Wald, Duke University © Megan Keady Ahern 2012 The contribution that follows is greatly indebted to the groundbreaking work of Toni Cade Bambara, Barbara Christian, and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – brilliant, visionary women whom cancer took from us far too soon. Their work has such instructive and inspirational force still, so much potential still to unpack, so much theoretical and cultural work still to do. In the hope of in some small way carrying forward their legacy, this dissertation is dedicated to them. ii Acknowledgements Throughout the course of this project I have been spoiled with a truly extraordinary dissertation committee. The chapters that follow would not have been possible without my marvelous chair, Michael Awkward, who combines a persistent dedication to incisive feminist literary criticism, an openness to new interdisciplinary approaches, and the patience and humor necessary to see a project as unlikely as this one through. Tiya Miles has continually astonished and inspired me with her brilliant, endlessly thoughtful and kind guidance, and taught me the meaning of “constructive criticism” through her uniquely wonderful dedication to patient, contemplative readings that coax the greatest possible power and meaning from a work, and from it build toward new insights.