Archival Explorations of Climate Variability and Social Vulnerability in Colonial Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TCA 049.Pdf (2.027Mb)

Detección de la tendencia local del cambio de la temperatura en México • René Lobato-Sánchez* • Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua, Jiutepec, México *Autor para correspondencia • Miguel Ángel Altamirano-del-Carmen • Consultor, Ciudad de México, México DOI: 10.24850/j-tyca-2017-06-07 Resumen Abstract Lobato-Sánchez, R., & Altamirano-del-Carmen, M. A. Lobato-Sánchez, R., & Altamirano-del-Carmen, M. A. (November- (noviembre-diciembre, 2017). Detección de la tendencia local December, 2017). Detection of local temperature trends in Mexico. del cambio de la temperatura en México. Tecnología y Ciencias Water Technology and Sciences (in Spanish), 8(6), 101-116, del Agua, 8(6), 101-116, DOI: 10.24850/j-tyca-2017-06-07. DOI: 10.24850/j-tyca-2017-06-07. Registros de temperatura indican que tres de cada cuatro Temperature records indicate that three of the four climatic stations estaciones climáticas evaluadas en México señalan un evaluated in Mexico show warming over the years 1950 to 2013, as calentamiento en el periodo 1950-2013, tomando como compared to the period 1961 to 1990 which was used as a baseline. referencia al periodo base 1961-1990. Después de un análisis After a complete analysis of climate records in Mexico, only 112 completo de registros climáticos en México, se determinó que were determined to have met the quality and standards required 101 solamente 112 registros cumplen con la calidad y estándares for the present study. From those, a subset of 20 stations with a requeridos para el presente estudio, de ahí se seleccionó, positive trend were randomly selected, which were representative de forma aleatoria, un subconjunto de 20 estaciones con of urban and rural areas distributed across Mexico. -

Location of Mexico Mexico Is the Second-Largest Country by Size and Population in Latin America

Read and Respond: Location, Climate, and Natural Resources of Mexico and Venezuela Location of Mexico Mexico is the second-largest country by size and population in Latin America. It is the largest Spanish- speaking country in the world. The country is located south of the United States. On the west is the Pacific Ocean, and on the east are the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Mexico’s location between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea allows it the opportunity to trade. There are seven major seaports in Mexico. Oil and other materials from Mexico can be easily shipped around the world to ports along the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Another advantage of Mexico’s location is that it is close to the United States. Because the two countries share a border, trade is easier. Railroads and trucks can be used to ship goods. Mexico’s main trading partner is the United States. Climate of Mexico Mexico has the Sierra Madre Mountains, deserts in the north, tropical beaches, plains, and plateaus. The climate varies according to the location, with some tropical areas receiving more than 40 inches of rain a year. Desert areas in the north remain dry most of the year. Most people live on the Central Plateau of Mexico in the central part of the country. Mexico City, one of the world’s largest cities, is in this region. There is arable (farmable) land in this region, and there is usually enough rain to grow a variety of crops. The region has many manufacturing centers, which provide jobs. -

Tourism, Heritage and Creativity: Divergent Narratives and Cultural Events in Mexican World Heritage Cities

Tourism, Heritage and Creativity: Divergent Narratives and Cultural Events in Mexican World Heritage Cities Tourismus, Erbe und Kreativität: Divergierende Erzählungen und kulturelle Ereignisse in mexi-kanischen Weltkulturerbe-Städten MARCO HERNÁNDEZ-ESCAMPA, DANIEL BARRERA-FERNÁNDEZ** Faculty of Architecture “5 de Mayo”, Autonomous University of Oaxaca “Benito Juárez” Abstract This work compares two major Mexican events held in World Heritage cities. Gua- najuato is seat to The Festival Internacional Cervantino. This festival represents the essence of a Mexican region that highlights the Hispanic past as part of its identity discourse. Meanwhile, Oaxaca is famous because of the Guelaguetza, an indigenous traditional festival whose roots go back in time for fve centuries. Focused on cultural change and sustainability, tourist perception, identity narrative, and city theming, the analysis included anthropological and urban views and methodologies. Results show high contrasts between the analyzed events, due in part to antagonist (Indigenous vs. Hispanic) identities. Such tension is characteristic not only in Mexico but in most parts of Latin America, where cultural syncretism is still ongoing. Dieser Beitrag vergleicht Großveranstaltungen zweier mexikanischer Städte mit Welt- kulturerbe-Status. Das Festival Internacional Cervantino in Guanajato steht beispiel- haft für eine mexikanische Region, die ihre spanische Vergangenheit als Bestandteil ihres Identitätsdiskurses zelebriert. Oaxaca wiederum ist für das indigene traditionelle Festival Guelaguetza bekannt, dessen Vorläufer 500 Jahre zurückreichen. Mit einem Fokus auf kulturellen Wandel und Nachhaltigkeit, Tourismus, Identitätserzählungen und städtisches Themenmanagement kombiniert die Analyse Perspektiven und Me- thoden aus der Anthropologie und Stadtforschung. Die Ergebnisse zeigen prägnante Unterschiede zwischen den beiden Festivals auf, die sich u.a. auf antagonistische Iden- titäten (indigene vs. -

Impact of Land-Use Changes on the Climate of the Mexico City Region

Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía, UNAM Ernesto Jáuregui ISSN 0188-4611, Núm. 55, 2004, pp. 46-60 Impact of land-use changes on the climate of the Mexico City Region Ernesto Jáuregui* Recibido: 17 de junio de 2004 Aceptado en versión final: 21 de septiembre de 2004 Abstract. It is well established that anthropogenic land-use changes directly affect the atmospheric boundary layer at the mesoscale dimensions. Located in the high lands of Central Mexico, the basin of Mexico (7 500 km2) has undergone a widespread conversion of natural vegetation to urban and agricultural land by deforestation. While the urban extension of the capital city occupied 6% of the basin in 1960, at the end of the twentieth century the urban sprawl had increased considerably to 20% of the total area. This phenomenal growth has impacted on the thermal climate of substantial portions of the basin. In this paper using annual temperature and precipitation data for a 25 year period, an attempt is made to identify interdecadal climate changes. Results show that large areas of the basin have changed toward a warmer drier climate. While afternoon temperatures have increased at a rate of 0.07° C/yr in the suburbs of the city the corresponding area averaged value for the rural sites is somewhat less: 0.06° C/yr. The afternoon temperature increase for the total number of stations used was 0.06° C/yr. The area-averaged minimum temperature increase in suburban stations (3) was 0.15° C/yr while that corresponding to surrounding rural sites was 0.08° C/yr for period 1961-1985. -

The Urban Climate of Mexico City

298 Erdkunde Band XXVII Kawagoe und Shiba einem doppelten Spannungsver der Landflucht ist jedoch aus Kapazitatsgriinden si haltnis ausgesetzt. Als zentripetale Zentralorte und cher. Wanderungszentren sind sie fiir ein weiteres Hinter 2. Hauptanziehungsgebiet werden die grofistadtorien land kaum besonders attraktiv. Die Zentralisations tierten pazifischen Ballungsraume bleiben. Dabei spannungen fiihren iiber sie hinaus direkt zum Haupt wird sich eine weitere zunehmend grofiraumige zentrum. von Ihre Entwicklung wird zentrifugalen der in mit - Ausweitung Ballungszonen Verbindung Kraften der Sie Ballungskerne gesteuert. wachsen, dem Bau neuer Strecken des Schienenschnellver aus - jedoch nicht eigener Kraft sondern als Satelliten. kehrs und neuer Autobahnen abzeichnen. Demgegenuber steht die sich eigenstandig verstar 3. Eine weitere Verstarkung der zwischenstadtischen kende regionale Vormacht der Prafektur-Hauptorte, Wanderungen wird sich auch auf den Austausch die echte Regionalzentren geworden sind. Sobald es zwischen den Ballungsgebieten auswirken. Eine Stu ihnen gelang, konkurrierende Nachbarstadte funktio wird sich nur da vollziehen, wo kla nal zu iiberschichtenund zu iiberholen, fenwanderung grofienmafiig re zentralortliche Hierarchien vorliegen. wuchs und wachst ihr Vorsprung unaufhaltsam wei ter.Das istAomori gegeniiberHirosaki erst halb, Sap 4. Das Prinzip der Wanderungs-Zentralitat aufierhalb erster den poro gegeniiber Asahikawa und Otaru bereits voll ge der Ballungsgebiete wird in Linie grofie ren mit mehr als 300 000 Einwoh lungen. Mentalitat und Wanderungsverhalten der ja Regionalzentren nern wer panischen Bevolkerung unterstutzen den Prozefi der zugute kommen. Kleinere Landeszentren Selbstverstarkung, der das Modell des ?Grofien To den mit der Ausdunnung ihres landlichen Umlandes Prafektur kyo" auf verschiedene ?Klein-Tokyos" im ganzen weiter abnehmen. Die dominierenden werden am starksten weiterwachsen. Land ubertragt. Hauptstadte Es wird abzuwarten sein, in welchem Mafie die zur des neuen Minister D. -

El PINGUICO NI43-101

NI 43-101 TECHNICAL REPORT FOR EL PINGUICO PROJECT GUANAJUATO MINING DISTRICT, MEXICO Guanajuato City, Guanajuato State Mexico Nearby Central coordinates 20°58' Latitude N, 101°13' longitude W Prepared for VANGOLD RESOURCES LTD. 1780-400 Burrard Street Vancouver, British Columbia V6C 3A6 Report By: Carlos Cham Domínguez, C.P.G. Consulting Geological Engineer Effective Date: February 28, 2017 1 DATE AND SIGNATURE PAGE AUTHOR CERTIFICATION I, Carlos Cham Domínguez, am Certified Professional Geologist and work for FINDORE S.A. DE C.V. located at Marco Antonio 100, col. Villa Magna, San Luis Potosi, S.L.P., Mexico 78210. This certificate applies to the technical report entitled NI 43-101 Technical Report for El Pinguico Project, Guanajuato Mining District, Mexico, with an effective date of February 28, 2017. I am a Certified Professional Geologist in good standing with the American Institute of Professional Geologists (AIPG) with registration number CPG-11760. I graduated with a bachelor degree in Geology from the Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí (Mexico) in 2003. I graduated with a MBA (finance) degree from the Universidad Tec Milenio (Mexico) in 2012 and I have a diploma in Mining and Environment from the University Miguel de Cervantes (Spain) in 2013. I have practiced my profession continuously for 13 years and have been involved in: mineral exploration and mine geology on gold and silver properties in Mexico. As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43-101. I visited the El Pinguico Project between the 2nd and 5th of January, 2017. -

Where Nomads Go Need to Know to Need

Art & Cities Nature 1 Welcome Culture & Towns & Wildlife Adventure Need to Know worldnomads.com Where Nomads Go Nomads Where your way from coast to coast. the curl at Puerto Escondido, and eat the curl at Puerto Escondido, an ancient pyramid at Muyil, shoot Dive with manatees in Xcalak, climb MEXICO 2 worldnomads.com World Nomads’ purpose is to challenge Contents travelers to harness their curiosity, be Adam Wiseman WELCOME WELCOME 3 brave enough to find their own journey, and to gain a richer understanding of Essential Mexico 4 Spanning almost 760,000mi² (2 million km²), with landscapes themselves, others, and the world. that range from snow-capped volcanos to dense rainforest, ART & CULTURE 6 and a cultural mix that’s equally diverse, Mexico can’t be How to Eat Mexico 8 contained in a handful of pages, so we’re not going to try. The Princess of the Pyramid 14 Think of this guide as a sampler plate, or a series of windows into Mexico – a selection of first-hand accounts from nomads Welcome The Muxes of Juchitán de Zaragoza 16 who’ve danced at the festivals, climbed the pyramids, chased Beyond Chichén Itzá 20 the waves, and connected with the locals. Meeting the World’s Authority Join our travelers as they kayak with sea turtles and manta on Mexican Folk Art 24 rays in Baja, meet the third-gender muxes of Juchitán, CITIES & TOWNS 26 unravel ancient Maya mysteries in the Yucatán, and take a Culture Mexico City: A Capital With Charisma 28 crash course in mole-making in Oaxaca. -

Xmas 2014 Catalog WEB.Pdf

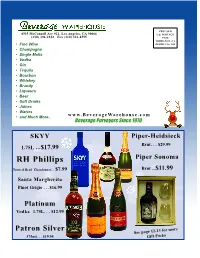

PRST STD 4935 McConnell Ave #21, Los Angeles, CA 90066 U.S. POSTAGE (310) 306-2822 Fax (310) 821-4555 PAID TORRANCE, CA • Fine Wine PERMIT No. 102 • Champagne • Single Malts • Vodka • Gin • Tequila • Bourbon • Whiskey • Brandy • Liqueurs • Beer • Soft Drinks • Juices • Waters • and Much More.. www.BeverageWarehouse.com Beverage Purveyors Since 1970 SKYY Piper-Heidsieck Brut. $29.99 1.75L ...$17.99 RHRH PhillipsPhillips Piper Sonoma Toasted Head Chardonnay. $7.99 Brut ...$11.99 Santa Margherita Pinot Grigio . .$16.99 PlatinumPlatinum Vodka 1.75L. $12.99 PatrPatronon SilverSilver See page 12-13 for more 375ml. $19.95 Gift Packs 2014 Holiday Catalog (310) 306-2822 www.BeverageWarehouse.com Beverage Purveyors Since 1970 All Your Gift Giving Items Spirits pages 12-29 Found Here Over 8,000 Items in Stock Imported and Domestic Beer pages 30-31 (310) 306-2822 www.BeverageWarehouse.com Champagne and NOWNOW ININ STSTOCKOCK Sparkling Wines page 4-6 Tequila nearly 500 in stock Vodka over 300 in stock Cognac & Brandy over 250 in stock Rum over 250 in stock Whiskey over 300 in stock Scotch Blended & S.M. over 200 in stock Open To The Public 7 Days A Week Fine Wine pages 7-11 Over 1,500 Wines Monday - Saturday 9am - 6pm From Around the World Sunday 10am - 5pm We also deliver ... (310) 306-2822 ( Closed Christmas Day & New Year’s Day ) As seen in “West L.A. Shops” WINE SPECTATOR April 30th, 2003 “Award of Distinction” Over 10,000sq. ft. of Beverages ZAGAT SURVEY Non-Alcoholic Products Visit BeverageWarehouse.com From the 405 freeway, take the 90 freeway Westbound toward Marina Del Rey and exit at Culver BL. -

La Familia Drug Cartel: Implications for U.S-Mexican Security

Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE The Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) is part of the U.S. Army War College and is the strategic-level study agent for issues related to national security and military strategy with emphasis on geostrate- gic analysis. The mission of SSI is to use independent analysis to conduct strategic studies that develop policy recommendations on: • Strategy, planning, and policy for joint and combined employment of military forces; • Regional strategic appraisals; • The nature of land warfare; • Matters affecting the Army’s future; • The concepts, philosophy, and theory of strategy; and • Other issues of importance to the leadership of the Army. Studies produced by civilian and military analysts concern topics having strategic implications for the Army, the Department of De- fense, and the larger national security community. In addition to its studies, SSI publishes special reports on topics of special or immediate interest. These include edited proceedings of conferences and topically-oriented roundtables, expanded trip re- ports, and quick-reaction responses to senior Army leaders. The Institute provides a valuable analytical capability within the Army to address strategic and other issues in support of Army par- ticipation in national security policy formulation. LA FAMILIA DRUG CARTEL: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S-MEXICAN SECURITY George W. Grayson December 2010 The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. -

SS6G3 the Student Will Explain the Impact of Location, Climate, Distribution of Natu- Ral Resources, and Population Distribution on Latin America and the Caribbean

SS6G3 The student will explain the impact of location, climate, distribution of natu- ral resources, and population distribution on Latin America and the Caribbean. a. Compare how the location, climate, and natural resources of Mexico and Venezuela affect where people live and how they trade. LOCATION, CLIMATE, AND NATURAL RESOURCES OF MEXICO Location of Mexico Mexico is the second-largest country by size and population in Latin America. It is the largest Spanish-speaking country in the world. The country is located south of the United States. On the west is the Pacific Ocean, and on the east are the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Mexico’s location between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea allows it the opportunity to trade. There are seven major seaports in Mexico. Oil and other materials from Mexico can be easily shipped around the world to ports along the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Another advantage of Mexico’s location is that it is close to the United States. Because the two countries share a border, trade is easier. Railroads and trucks can be used to ship goods. Mexico’s main trading partner is the United States. Climate of Mexico AND CANADA LATIN AMERICA LATIN Mexico has the Sierra Madre Mountains, deserts in the north, tropical beaches, plains, and plateaus. The climate varies according to the location, with some tropical areas receiving more than 40 inches of rain a year. Desert areas in the north remain dry most of the year. Most people live on the Central Plateau of Mexico in the central part of the country. -

Biopolitical Itineraries

BIOPOLITICAL ITINERARIES: MEXICO IN CONTEMPORARY TOURIST LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by RYAN RASHOTTE In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November, 2011 © Ryan Rashotte, 2011 ABSTRACT BIOPOLITICAL ITINERARIES: MEXICO IN CONTEMPORARY TOURIST LITERATURE Ryan Rashotte Advisor: University of Guelph, 2011 Professor Martha Nandorfy This thesis is an investigation of representations of Mexico in twentieth century American and British literature. Drawing on various conceptions of biopolitics and biopower (from Foucault, Agamben and other theorists), I argue that the development of American pleasure tourism post-World War II has definitively transformed the biopolitical climate of Mexico for hosts and guests. Exploring the consolidation in Mexico of various forms of American pleasure tourism (my first chapter); cultures of vice and narco-tourism (my second chapter); and the erotic mixtures of sex and health that mark the beach resort (my third chapter), I posit an uncanny and perverse homology between the biopolitics of American tourists and Mexican labourers and qualify the neocolonial armature that links them together. Writers (from Jack Kerouac to Tennessee Williams) and intellectuals (from ethnobotanist R. Gordon Wasson to second-wave feminist Maryse Holder) have uniquely written contemporary “spaces of exception” in Mexico, have “founded” places where the normalizing discourses, performances of apparatuses of social control (in the U.S.) are made to have little consonance. I contrast the kinds of “lawlessness” and liminality white bodies at leisure and brown bodies at labour encounter and compel in their bare flesh, and investigate the various aesthetic discourses that underwrite the sovereignty and mobility of these bodies in late capitalism. -

Mexico

-, , ,FlillR-220 MEXICO:L~}F'EXPOHT~-~EJ<E~, PROFILE. (FOREIGN AGRICULTURA'L EC ONOMrCS REP!.) ! 0'. H • ROBERTS ,'ET AL. ECONOMIC RESEARCH SE,RYICE}' WASHINGTON, DC. rNTERNATIONAL ECONOMICS OIV. MAY 8,6 67P PB86-214426 Mexico:" An Export Matke1; Prof'ile ~ ',' \\ (tJ. S .) Economic Re~\earch Service, washington, DC May 86 c'rf:,'~:J_ ,"'~"":: . ',.'c';!l" ",c",e"i{ ':;'" 6'"' . ",. ..... "",.-:; o I " '!II ,0., CI. ' .., to • • • • USA Ship to: )11~XI(~f) • • • . TECHNICAL INFO MATION SERVICE u.s. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE SPRINGFIELD, VA. 22161 U212·IDI REPORT .. ~JCUMENTAnON II. HfIOWT MO• .'PAGE 1 FAER-220 L ...... DItte May 1986 Mex>i.co: An Export Harket Profile .. ~------------------------------------------------------------------i~~----------------------~7. Author(.) L .......nnI.. Orpftlzlitlon IIteot. No. Donna R. Roberts and Myles J. Mielke FAER-220 •. "'~"",I,. O,..ftlailtlon Name .ftd Add_ 10. .......naelllWAftI Unit No. International Economics Division -.---::--------~ Economic Research Service u. CcNItr..ct{C) or Qr8nt<G) Ho. U.S. Department of Agriculture le) Washington, D.C. 20005-4788 14. 15. Sup""omontary Hal.. \ \. ~; Mexico will1i~ely remain one of the top 10 markets for u.s. agricultural products through 1990, altho\'1gh its recent financial difficulties will reduce its imp~rts of nonbasic commodities in the next few years. Its steadily expanding population Ilnd highly variable weather will underpin expected increases of import.~ of grains and oUseeds. The United States is expected to retain its present position" as the dominant supplier of Mexico's agricultural imports because of the two countries' close trading relationships and well-· established marketing channels. Economic recovery in the late eighties wi.111argely determine the size and composition of Mexico's agricultural import bUt.