Biopolitical Itineraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16- PR-Marthagraham

! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 28, 2016 Media Contact: Dance Affiliates Anne-Marie Mulgrew, Director of Education & Special Projects 215-636-9000 ext. 110, [email protected] Carrie Hartman Grimm & Grove Communications [email protected] Editors: Images are available upon request. The legendary Martha Graham Dance Company makes a rare Philadelphia appearance with four Graham’s classics including Appalachian Spring November 3-6 (Philadelphia, PA) One of America’s most celebrated and visionary dance troupes, the Martha Graham Dance Company (MGDC), returns to Philadelphia after a decade on the NextMove Dance Series, November 3-6 in six performances at the Prince Theater, 1412 Chestnut Street. Named by Time Magazine as the “Dancer of the Century,” founder/choreographer Martha Graham has left a deep and lasting impact on American art and culture through her repertoire of 181 works. The program includes Graham’s masterworks Appalachian Spring, Errand into the Maze, Dark Meadow Suite and a re- imaging of Graham’s poignant solo Lamentation in Lamentation Variations by contemporary choreographers. Performances take place Thursday, November 3 at 7:30pm; Friday, November 4 at 8:00pm; Saturday, November 5 at 2:00pm and 8:00 pm; and Sunday, November 6 at 2:30pm and 7:30pm. Tickets cost $20-$60 and can be purchased in person at the Prince Theater box office, by phone 215-422-4580 or online http://princetheater.org/next-move. Opening the program is Dark Meadow Suite (2016), set to Mexican composer Carlos Chavez’s music. Artistic Director Janet Eilber rearranged highlights from one of Graham’s most psychological, controversial, and abstract works. -

TCA 049.Pdf (2.027Mb)

Detección de la tendencia local del cambio de la temperatura en México • René Lobato-Sánchez* • Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua, Jiutepec, México *Autor para correspondencia • Miguel Ángel Altamirano-del-Carmen • Consultor, Ciudad de México, México DOI: 10.24850/j-tyca-2017-06-07 Resumen Abstract Lobato-Sánchez, R., & Altamirano-del-Carmen, M. A. Lobato-Sánchez, R., & Altamirano-del-Carmen, M. A. (November- (noviembre-diciembre, 2017). Detección de la tendencia local December, 2017). Detection of local temperature trends in Mexico. del cambio de la temperatura en México. Tecnología y Ciencias Water Technology and Sciences (in Spanish), 8(6), 101-116, del Agua, 8(6), 101-116, DOI: 10.24850/j-tyca-2017-06-07. DOI: 10.24850/j-tyca-2017-06-07. Registros de temperatura indican que tres de cada cuatro Temperature records indicate that three of the four climatic stations estaciones climáticas evaluadas en México señalan un evaluated in Mexico show warming over the years 1950 to 2013, as calentamiento en el periodo 1950-2013, tomando como compared to the period 1961 to 1990 which was used as a baseline. referencia al periodo base 1961-1990. Después de un análisis After a complete analysis of climate records in Mexico, only 112 completo de registros climáticos en México, se determinó que were determined to have met the quality and standards required 101 solamente 112 registros cumplen con la calidad y estándares for the present study. From those, a subset of 20 stations with a requeridos para el presente estudio, de ahí se seleccionó, positive trend were randomly selected, which were representative de forma aleatoria, un subconjunto de 20 estaciones con of urban and rural areas distributed across Mexico. -

Location of Mexico Mexico Is the Second-Largest Country by Size and Population in Latin America

Read and Respond: Location, Climate, and Natural Resources of Mexico and Venezuela Location of Mexico Mexico is the second-largest country by size and population in Latin America. It is the largest Spanish- speaking country in the world. The country is located south of the United States. On the west is the Pacific Ocean, and on the east are the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Mexico’s location between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea allows it the opportunity to trade. There are seven major seaports in Mexico. Oil and other materials from Mexico can be easily shipped around the world to ports along the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Another advantage of Mexico’s location is that it is close to the United States. Because the two countries share a border, trade is easier. Railroads and trucks can be used to ship goods. Mexico’s main trading partner is the United States. Climate of Mexico Mexico has the Sierra Madre Mountains, deserts in the north, tropical beaches, plains, and plateaus. The climate varies according to the location, with some tropical areas receiving more than 40 inches of rain a year. Desert areas in the north remain dry most of the year. Most people live on the Central Plateau of Mexico in the central part of the country. Mexico City, one of the world’s largest cities, is in this region. There is arable (farmable) land in this region, and there is usually enough rain to grow a variety of crops. The region has many manufacturing centers, which provide jobs. -

Impact of Land-Use Changes on the Climate of the Mexico City Region

Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía, UNAM Ernesto Jáuregui ISSN 0188-4611, Núm. 55, 2004, pp. 46-60 Impact of land-use changes on the climate of the Mexico City Region Ernesto Jáuregui* Recibido: 17 de junio de 2004 Aceptado en versión final: 21 de septiembre de 2004 Abstract. It is well established that anthropogenic land-use changes directly affect the atmospheric boundary layer at the mesoscale dimensions. Located in the high lands of Central Mexico, the basin of Mexico (7 500 km2) has undergone a widespread conversion of natural vegetation to urban and agricultural land by deforestation. While the urban extension of the capital city occupied 6% of the basin in 1960, at the end of the twentieth century the urban sprawl had increased considerably to 20% of the total area. This phenomenal growth has impacted on the thermal climate of substantial portions of the basin. In this paper using annual temperature and precipitation data for a 25 year period, an attempt is made to identify interdecadal climate changes. Results show that large areas of the basin have changed toward a warmer drier climate. While afternoon temperatures have increased at a rate of 0.07° C/yr in the suburbs of the city the corresponding area averaged value for the rural sites is somewhat less: 0.06° C/yr. The afternoon temperature increase for the total number of stations used was 0.06° C/yr. The area-averaged minimum temperature increase in suburban stations (3) was 0.15° C/yr while that corresponding to surrounding rural sites was 0.08° C/yr for period 1961-1985. -

The Urban Climate of Mexico City

298 Erdkunde Band XXVII Kawagoe und Shiba einem doppelten Spannungsver der Landflucht ist jedoch aus Kapazitatsgriinden si haltnis ausgesetzt. Als zentripetale Zentralorte und cher. Wanderungszentren sind sie fiir ein weiteres Hinter 2. Hauptanziehungsgebiet werden die grofistadtorien land kaum besonders attraktiv. Die Zentralisations tierten pazifischen Ballungsraume bleiben. Dabei spannungen fiihren iiber sie hinaus direkt zum Haupt wird sich eine weitere zunehmend grofiraumige zentrum. von Ihre Entwicklung wird zentrifugalen der in mit - Ausweitung Ballungszonen Verbindung Kraften der Sie Ballungskerne gesteuert. wachsen, dem Bau neuer Strecken des Schienenschnellver aus - jedoch nicht eigener Kraft sondern als Satelliten. kehrs und neuer Autobahnen abzeichnen. Demgegenuber steht die sich eigenstandig verstar 3. Eine weitere Verstarkung der zwischenstadtischen kende regionale Vormacht der Prafektur-Hauptorte, Wanderungen wird sich auch auf den Austausch die echte Regionalzentren geworden sind. Sobald es zwischen den Ballungsgebieten auswirken. Eine Stu ihnen gelang, konkurrierende Nachbarstadte funktio wird sich nur da vollziehen, wo kla nal zu iiberschichtenund zu iiberholen, fenwanderung grofienmafiig re zentralortliche Hierarchien vorliegen. wuchs und wachst ihr Vorsprung unaufhaltsam wei ter.Das istAomori gegeniiberHirosaki erst halb, Sap 4. Das Prinzip der Wanderungs-Zentralitat aufierhalb erster den poro gegeniiber Asahikawa und Otaru bereits voll ge der Ballungsgebiete wird in Linie grofie ren mit mehr als 300 000 Einwoh lungen. Mentalitat und Wanderungsverhalten der ja Regionalzentren nern wer panischen Bevolkerung unterstutzen den Prozefi der zugute kommen. Kleinere Landeszentren Selbstverstarkung, der das Modell des ?Grofien To den mit der Ausdunnung ihres landlichen Umlandes Prafektur kyo" auf verschiedene ?Klein-Tokyos" im ganzen weiter abnehmen. Die dominierenden werden am starksten weiterwachsen. Land ubertragt. Hauptstadte Es wird abzuwarten sein, in welchem Mafie die zur des neuen Minister D. -

BTC Catalog 172.Pdf

Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. ~ Catalog 172 ~ First Books & Before 112 Nicholson Rd., Gloucester City NJ 08030 ~ (856) 456-8008 ~ [email protected] Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept checks, VISA, MASTERCARD, AMERICAN EXPRESS, DISCOVER, and PayPal. Gift certificates available. Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. Member ABAA, ILAB. Artwork by Tom Bloom. © 2011 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. www.betweenthecovers.com After 171 catalogs, we’ve finally gotten around to a staple of the same). This is not one of them, nor does it pretend to be. bookselling industry, the “First Books” catalog. But we decided to give Rather, it is an assemblage of current inventory with an eye toward it a new twist... examining the question, “Where does an author’s career begin?” In the The collecting sub-genre of authors’ first books, a time-honored following pages we have tried to juxtapose first books with more obscure tradition, is complicated by taxonomic problems – what constitutes an (and usually very inexpensive), pre-first book material. -

Hart Crane's Neo-Symbolist Poetics" (2006)

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scholar Commons | University of South Florida Research University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2006 "Mingling Incantations": Hart Crane's Neo- Symbolist Poetics Christopher A. Tidwell University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Tidwell, Christopher A., ""Mingling Incantations": Hart Crane's Neo-Symbolist Poetics" (2006). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2727 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Mingling Incantations": Hart Crane's Neo-Symbolist Poetics by Christopher A. Tidwell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D. Richard Dietrich, Ph.D. John Hatcher, Ph.D. Roberta Tucker, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 31, 2006 Keywords: french symbolism, symbolist poetry, modern poetry, influence, metaphor © Copyright 2006 , Christopher A. Tidwell Table of Contents Abstract ii Introduction: The Symbolist Aesthetic 1 Chapter One: Hart Crane and His Literary Critics 29 Chapter Two: T. S. Eliot, Hart Crane, and Literary Influence 110 Chapter Three: Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Crane 133 Chapter Four: Mallarmé and Crane’s Neo-Symbolist Poetics 148 Works Cited 164 Bibliography 177 About the Author End Page i “Mingling Incantations”: Hart Crane’s Neo-Symbolist Poetics Christopher A. -

Xmas 2014 Catalog WEB.Pdf

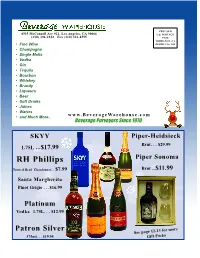

PRST STD 4935 McConnell Ave #21, Los Angeles, CA 90066 U.S. POSTAGE (310) 306-2822 Fax (310) 821-4555 PAID TORRANCE, CA • Fine Wine PERMIT No. 102 • Champagne • Single Malts • Vodka • Gin • Tequila • Bourbon • Whiskey • Brandy • Liqueurs • Beer • Soft Drinks • Juices • Waters • and Much More.. www.BeverageWarehouse.com Beverage Purveyors Since 1970 SKYY Piper-Heidsieck Brut. $29.99 1.75L ...$17.99 RHRH PhillipsPhillips Piper Sonoma Toasted Head Chardonnay. $7.99 Brut ...$11.99 Santa Margherita Pinot Grigio . .$16.99 PlatinumPlatinum Vodka 1.75L. $12.99 PatrPatronon SilverSilver See page 12-13 for more 375ml. $19.95 Gift Packs 2014 Holiday Catalog (310) 306-2822 www.BeverageWarehouse.com Beverage Purveyors Since 1970 All Your Gift Giving Items Spirits pages 12-29 Found Here Over 8,000 Items in Stock Imported and Domestic Beer pages 30-31 (310) 306-2822 www.BeverageWarehouse.com Champagne and NOWNOW ININ STSTOCKOCK Sparkling Wines page 4-6 Tequila nearly 500 in stock Vodka over 300 in stock Cognac & Brandy over 250 in stock Rum over 250 in stock Whiskey over 300 in stock Scotch Blended & S.M. over 200 in stock Open To The Public 7 Days A Week Fine Wine pages 7-11 Over 1,500 Wines Monday - Saturday 9am - 6pm From Around the World Sunday 10am - 5pm We also deliver ... (310) 306-2822 ( Closed Christmas Day & New Year’s Day ) As seen in “West L.A. Shops” WINE SPECTATOR April 30th, 2003 “Award of Distinction” Over 10,000sq. ft. of Beverages ZAGAT SURVEY Non-Alcoholic Products Visit BeverageWarehouse.com From the 405 freeway, take the 90 freeway Westbound toward Marina Del Rey and exit at Culver BL. -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

SS6G3 the Student Will Explain the Impact of Location, Climate, Distribution of Natu- Ral Resources, and Population Distribution on Latin America and the Caribbean

SS6G3 The student will explain the impact of location, climate, distribution of natu- ral resources, and population distribution on Latin America and the Caribbean. a. Compare how the location, climate, and natural resources of Mexico and Venezuela affect where people live and how they trade. LOCATION, CLIMATE, AND NATURAL RESOURCES OF MEXICO Location of Mexico Mexico is the second-largest country by size and population in Latin America. It is the largest Spanish-speaking country in the world. The country is located south of the United States. On the west is the Pacific Ocean, and on the east are the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Mexico’s location between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea allows it the opportunity to trade. There are seven major seaports in Mexico. Oil and other materials from Mexico can be easily shipped around the world to ports along the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Another advantage of Mexico’s location is that it is close to the United States. Because the two countries share a border, trade is easier. Railroads and trucks can be used to ship goods. Mexico’s main trading partner is the United States. Climate of Mexico AND CANADA LATIN AMERICA LATIN Mexico has the Sierra Madre Mountains, deserts in the north, tropical beaches, plains, and plateaus. The climate varies according to the location, with some tropical areas receiving more than 40 inches of rain a year. Desert areas in the north remain dry most of the year. Most people live on the Central Plateau of Mexico in the central part of the country. -

Mexico

-, , ,FlillR-220 MEXICO:L~}F'EXPOHT~-~EJ<E~, PROFILE. (FOREIGN AGRICULTURA'L EC ONOMrCS REP!.) ! 0'. H • ROBERTS ,'ET AL. ECONOMIC RESEARCH SE,RYICE}' WASHINGTON, DC. rNTERNATIONAL ECONOMICS OIV. MAY 8,6 67P PB86-214426 Mexico:" An Export Matke1; Prof'ile ~ ',' \\ (tJ. S .) Economic Re~\earch Service, washington, DC May 86 c'rf:,'~:J_ ,"'~"":: . ',.'c';!l" ",c",e"i{ ':;'" 6'"' . ",. ..... "",.-:; o I " '!II ,0., CI. ' .., to • • • • USA Ship to: )11~XI(~f) • • • . TECHNICAL INFO MATION SERVICE u.s. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE SPRINGFIELD, VA. 22161 U212·IDI REPORT .. ~JCUMENTAnON II. HfIOWT MO• .'PAGE 1 FAER-220 L ...... DItte May 1986 Mex>i.co: An Export Harket Profile .. ~------------------------------------------------------------------i~~----------------------~7. Author(.) L .......nnI.. Orpftlzlitlon IIteot. No. Donna R. Roberts and Myles J. Mielke FAER-220 •. "'~"",I,. O,..ftlailtlon Name .ftd Add_ 10. .......naelllWAftI Unit No. International Economics Division -.---::--------~ Economic Research Service u. CcNItr..ct{C) or Qr8nt<G) Ho. U.S. Department of Agriculture le) Washington, D.C. 20005-4788 14. 15. Sup""omontary Hal.. \ \. ~; Mexico will1i~ely remain one of the top 10 markets for u.s. agricultural products through 1990, altho\'1gh its recent financial difficulties will reduce its imp~rts of nonbasic commodities in the next few years. Its steadily expanding population Ilnd highly variable weather will underpin expected increases of import.~ of grains and oUseeds. The United States is expected to retain its present position" as the dominant supplier of Mexico's agricultural imports because of the two countries' close trading relationships and well-· established marketing channels. Economic recovery in the late eighties wi.111argely determine the size and composition of Mexico's agricultural import bUt. -

"Equivalents": Spirituality in the 1920S Work of Stieglitz

The Intimate Gallery and the Equivalents: Spirituality in the 1920s Work of Stieglitz Kristina Wilson With a mixture of bitterness and yearning, Alfred Stieglitz Galleries of the Photo-Secession, where he had shown work wrote to Sherwood Anderson in December 1925 describing by both American and European modernists), the Intimate the gallery he had just opened in a small room in New York Gallery was Stieglitz's first venture dedicated solely to the City. The Intimate Gallery, as he called it, was to be devoted promotion of a national art.3 It operated in room 303 of the to the work of a select group of contemporary American Anderson Galleries Building on Park Avenue for four sea- artists. And although it was a mere 20 by 26 feet, he discussed sons, from when Stieglitz was sixty-one years of age until he the space as if it were enormous-perhaps limitless: was sixty-five; after the Intimate Gallery closed, he opened An American Place on Madison Avenue, which he ran until his There is no artiness-Just a throbbing pulsating.... I told death in 1946. It is at the Intimate Gallery, where he primarily a dealer who seemed surprised that I should be making showed the work of Arthur Dove, John Marin, Georgia this new "experiment"-[that] I had no choice-that O'Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and Paul Strand, that the ideals there were things called fish and things called birds. That and aspirations motivating his late-life quest for a unique, fish seemed happiest in water-&8 birds seemed happy in homegrown school of art can be found in their clearest and the air.