Hart Crane's Neo-Symbolist Poetics" (2006)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16- PR-Marthagraham

! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 28, 2016 Media Contact: Dance Affiliates Anne-Marie Mulgrew, Director of Education & Special Projects 215-636-9000 ext. 110, [email protected] Carrie Hartman Grimm & Grove Communications [email protected] Editors: Images are available upon request. The legendary Martha Graham Dance Company makes a rare Philadelphia appearance with four Graham’s classics including Appalachian Spring November 3-6 (Philadelphia, PA) One of America’s most celebrated and visionary dance troupes, the Martha Graham Dance Company (MGDC), returns to Philadelphia after a decade on the NextMove Dance Series, November 3-6 in six performances at the Prince Theater, 1412 Chestnut Street. Named by Time Magazine as the “Dancer of the Century,” founder/choreographer Martha Graham has left a deep and lasting impact on American art and culture through her repertoire of 181 works. The program includes Graham’s masterworks Appalachian Spring, Errand into the Maze, Dark Meadow Suite and a re- imaging of Graham’s poignant solo Lamentation in Lamentation Variations by contemporary choreographers. Performances take place Thursday, November 3 at 7:30pm; Friday, November 4 at 8:00pm; Saturday, November 5 at 2:00pm and 8:00 pm; and Sunday, November 6 at 2:30pm and 7:30pm. Tickets cost $20-$60 and can be purchased in person at the Prince Theater box office, by phone 215-422-4580 or online http://princetheater.org/next-move. Opening the program is Dark Meadow Suite (2016), set to Mexican composer Carlos Chavez’s music. Artistic Director Janet Eilber rearranged highlights from one of Graham’s most psychological, controversial, and abstract works. -

A History of Poetics

A HISTORY OF POETICS German Scholarly Poetics and Aesthetics in International Context, 1770-1960 Sandra Richter With a Bibliography of Poetics by Anja Hill-Zenk, Jasmin Azazmah, Eva Jost and Sandra Richter 1 To Jörg Schönert 2 Table of Contents Preface 5 I. Introduction 9 1. Poetics as Field of Knowledge 11 2. Periods and Text Types 21 3. Methodology 26 II. Aesthetics and Academic Poetics in Germany 32 1. Eclectic Poetics: Popular Philosophy (1770í 36 (a) The Moralizing Standard Work: Johann Georg Sulzer (1771í 39 (b) Popular Aesthetics as a Part of ‘Erfahrungsseelenlehre’ in 1783: Johann Joachim Eschenburg, Johann August Eberhard, Johann Jacob Engel 44 2. Transcendental Poetics and Beyond: Immanuel Kant’s Critical Successors (1790í1800) 55 (a) Critical Poetics and Popular Critique: Johann Heinrich Gottlob Heusinger (1797) 57 (b) Systematical and Empirical Poetics on a Cosmological Basis: Christian A.H. Clodius (1804) 59 (c) Towards a Realistic Poetics: Joseph Hillebrand (1827) 63 3. Historical and Genetic Poetics: Johann Justus Herwig (1774), August Wilhelm Schlegel (1801í1803/1809í1811) and Johann Gottfried Herder’s Heritage 66 4. Logostheological Poetics after Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling: Friedrich Ast (1805) and Joseph Loreye (1801/2, ²1820) 77 5. Post-idealist Poetics 86 (a) An Empirical Idealist Poetics: Friedrich Bouterwek (1806) 86 (b) Religious Poetics: Wilhelm Wackernagel’s Lectures (1836/7) and the Catholics 90 (c) The Turning Point after Hegel and Beyond: Friedrich Theodor Vischer (1846í DQGWKH1HZ&KDOOHQJHV (Johann Friedrich Herbart, Robert Zimmermann) 96 (d) Literary Poetics: Rudolph Gottschall (1858) 103 6. Pre-Empirical and Empirical Poetics since 1820 111 (a) Poetics as Life Science: Moriz Carriere (1854/²1884) and (1859) 113 (b) Psychological Poetics: From Gustav Theodor Fechner (1871/1876), 3 Heinrich Viehoff (1820) and Rudolph Hermann Lotze (1884) to Wilhelm Dilthey (1887) to Richard Müller-Freienfels (1914/²1921) 117 (c) Processual Poetics: Wilhelm Scherer (1888) 142 (d) Evolutionary Poetics: Eugen Wolff (1899) 149 7. -

Symbolism - the Poetics of Associations and an Artistic Interpretation of the Text in the Works of the Symbolists

Mental Enlightenment Scientific-Methodological Journal Volume 2021 Issue 4 Article 11 8-1-2021 SYMBOLISM - THE POETICS OF ASSOCIATIONS AND AN ARTISTIC INTERPRETATION OF THE TEXT IN THE WORKS OF THE SYMBOLISTS Ulugbek Jabbarov Jizzakh Branch of National University of Uzbekistan, [email protected] Ulugbek Turgunov Jizzakh Branch of National University of Uzbekistan, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uzjournals.edu.uz/tziuj Part of the Education Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Language Interpretation and Translation Commons Recommended Citation Jabbarov, Ulugbek and Turgunov, Ulugbek (2021) "SYMBOLISM - THE POETICS OF ASSOCIATIONS AND AN ARTISTIC INTERPRETATION OF THE TEXT IN THE WORKS OF THE SYMBOLISTS," Mental Enlightenment Scientific-Methodological Journal: Vol. 2021 : Iss. 4 , Article 11. Available at: https://uzjournals.edu.uz/tziuj/vol2021/iss4/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by 2030 Uzbekistan Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mental Enlightenment Scientific-Methodological Journal by an authorized editor of 2030 Uzbekistan Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYMBOLISM - THE POETICS OF ASSOCIATIONS AND AN ARTISTIC INTERPRETATION OF THE TEXT IN THE WORKS OF THE SYMBOLISTS Ulugbek Jabbarov, Jizzakh Branch of National University of Uzbekistan E-mail address: [email protected] Ulugbek Turgunov, Jizzakh Branch of National University of Uzbekistan E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract: This article is about an artistic interpretation of the text in the works of the symbolists. It discusses , the colorful and multifaceted meaning of symbols strengthened in many associations in life and literature. Some artists tried to theoretically substantiate the purely associative connection of this sign with the perception of the viewer, and not with semantics. -

BTC Catalog 172.Pdf

Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. ~ Catalog 172 ~ First Books & Before 112 Nicholson Rd., Gloucester City NJ 08030 ~ (856) 456-8008 ~ [email protected] Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept checks, VISA, MASTERCARD, AMERICAN EXPRESS, DISCOVER, and PayPal. Gift certificates available. Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. Member ABAA, ILAB. Artwork by Tom Bloom. © 2011 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. www.betweenthecovers.com After 171 catalogs, we’ve finally gotten around to a staple of the same). This is not one of them, nor does it pretend to be. bookselling industry, the “First Books” catalog. But we decided to give Rather, it is an assemblage of current inventory with an eye toward it a new twist... examining the question, “Where does an author’s career begin?” In the The collecting sub-genre of authors’ first books, a time-honored following pages we have tried to juxtapose first books with more obscure tradition, is complicated by taxonomic problems – what constitutes an (and usually very inexpensive), pre-first book material. -

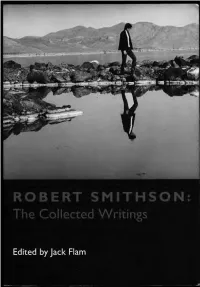

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

Biopolitical Itineraries

BIOPOLITICAL ITINERARIES: MEXICO IN CONTEMPORARY TOURIST LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by RYAN RASHOTTE In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November, 2011 © Ryan Rashotte, 2011 ABSTRACT BIOPOLITICAL ITINERARIES: MEXICO IN CONTEMPORARY TOURIST LITERATURE Ryan Rashotte Advisor: University of Guelph, 2011 Professor Martha Nandorfy This thesis is an investigation of representations of Mexico in twentieth century American and British literature. Drawing on various conceptions of biopolitics and biopower (from Foucault, Agamben and other theorists), I argue that the development of American pleasure tourism post-World War II has definitively transformed the biopolitical climate of Mexico for hosts and guests. Exploring the consolidation in Mexico of various forms of American pleasure tourism (my first chapter); cultures of vice and narco-tourism (my second chapter); and the erotic mixtures of sex and health that mark the beach resort (my third chapter), I posit an uncanny and perverse homology between the biopolitics of American tourists and Mexican labourers and qualify the neocolonial armature that links them together. Writers (from Jack Kerouac to Tennessee Williams) and intellectuals (from ethnobotanist R. Gordon Wasson to second-wave feminist Maryse Holder) have uniquely written contemporary “spaces of exception” in Mexico, have “founded” places where the normalizing discourses, performances of apparatuses of social control (in the U.S.) are made to have little consonance. I contrast the kinds of “lawlessness” and liminality white bodies at leisure and brown bodies at labour encounter and compel in their bare flesh, and investigate the various aesthetic discourses that underwrite the sovereignty and mobility of these bodies in late capitalism. -

"Equivalents": Spirituality in the 1920S Work of Stieglitz

The Intimate Gallery and the Equivalents: Spirituality in the 1920s Work of Stieglitz Kristina Wilson With a mixture of bitterness and yearning, Alfred Stieglitz Galleries of the Photo-Secession, where he had shown work wrote to Sherwood Anderson in December 1925 describing by both American and European modernists), the Intimate the gallery he had just opened in a small room in New York Gallery was Stieglitz's first venture dedicated solely to the City. The Intimate Gallery, as he called it, was to be devoted promotion of a national art.3 It operated in room 303 of the to the work of a select group of contemporary American Anderson Galleries Building on Park Avenue for four sea- artists. And although it was a mere 20 by 26 feet, he discussed sons, from when Stieglitz was sixty-one years of age until he the space as if it were enormous-perhaps limitless: was sixty-five; after the Intimate Gallery closed, he opened An American Place on Madison Avenue, which he ran until his There is no artiness-Just a throbbing pulsating.... I told death in 1946. It is at the Intimate Gallery, where he primarily a dealer who seemed surprised that I should be making showed the work of Arthur Dove, John Marin, Georgia this new "experiment"-[that] I had no choice-that O'Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and Paul Strand, that the ideals there were things called fish and things called birds. That and aspirations motivating his late-life quest for a unique, fish seemed happiest in water-&8 birds seemed happy in homegrown school of art can be found in their clearest and the air. -

©2007 Sunny Stalter ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2007 Sunny Stalter ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNDERGROUND SUBJECTS: PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION AND PERCEPTION IN NEW YORK MODERNIST LITERATURE by SUNNY STALTER A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Literatures in English written under the direction of Professor Elin Diamond and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2007 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Underground Subjects: Public Transportation and Perception in New York Modernist Literature By Sunny Stalter Dissertation Director: Professor Elin Diamond This dissertation investigates the relationship between public transportation and New York modernist literature. It argues that the experience of riding the subway and elevated train shapes the forms and themes of modernist writing, while textual representations of these spaces of transit in turn shape the modern understanding of urban subjectivity. Exploring the tension between the embodied, habitual ride and the abstract transportation system, New York modernist writers represent the sense of being in thrall to forces of modernity, interrogate the connection between space and psychology, and envision new pathways between the past and the present. I begin with an analysis of the intertwined discourses necessary to a consideration of modernism and public transportation, including visuality and spatial theory, the history of technology, and urban studies. Through readings of American Expressionist plays by Elmer Rice and Osip Dymov, I locate a modernist theatricality in the subway car, one centered on ideas of claustrophobia and fantasy. I then turn to Harlem Renaissance ii writers Rudolph Fisher and Walter White, whose migration narratives embrace the transitional potential of the mechanized journey North even as they warn against the illusory vision of Harlem seen from the subway steps. -

Aristotle's Poetics

Aristotle's Poetics José Angel García Landa Universidad de Zaragoza http://www.garcialanda.net 1. Introduction 2. The origins of literature 3. The nature of poetry 4. Theory of genres 5. Tragedy 6. Other genres 7. The Aristotelian heritage José Angel García Landa, "Aristotle's Poetics" 2 1. Introduction Aristotle (384-322 BC) was a disciple of Plato and the teacher of Alexander the Great. Plato's view of literature is heavily conditioned by the atmosphere of political concern which pervaded Athens at the time. Aristotle belongs to a later age, in which the role of Athens as a secondary minor power seems definitely settled. His view of literature does not answer to any immediate political theory, and consequently his critical approach is more intrinsic. Aristotle's work on the theory of literature is the treatise Peri poietikés, usually called the Poetics (ca. 330 BC). Only part of it has survived, and that in the form of notes for a course, and not as a developed theoretical treatise. Aristotle's theory of literature may be considered to be the answer to Plato's. Of course, he does much more than merely answer. He develops a whole theory of his own which is opposed to Plato's much as their whole philosophical systems are opposed to each other. For Aristotle as for Plato, the theory of literature is only a part of a general theory of reality. This means that an adequate reading of the Poetics 1 must take into account the context of Aristotelian theory which is defined above all by the Metaphysics, the Ethics, the Politics and the Rhetoric. -

1 a Queer Orientation: the Sexual Geographies of Modernism 1913

A Queer Orientation: The Sexual Geographies of Modernism 1913-1939. Sean Richardson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2019 1 Copyright Statement. This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed in the owner(s) of the Intellectual Property Rights. 2 Dedication. For Katie, my favourite scream. Acknowledgements. Etymologically, the word ‘thank’ shares its roots with the Indo-European ‘tong-’, to ‘think’ and ‘feel’. When we give thanks today, we may consider the actions or words of others, but I find that tracing this root is generative—it allows me to consider who has helped me think through this thesis, as much as who has helped me feel my way. First, I must thank my supervisors, Andrew Thacker and Catherine Clay. Primarily, of course, my supervisory team has helped me to think: I thank them for pushing me as a reader, a critic and a writer, while giving me the space to work on other projects that have shored me up in myriad ways. And yet Andrew and Cathy have also allowed me to feel—they have given me the space to try, test, write and rewrite. -

The Problem of Literary Truth in Plato's Republic and Aristotle's

Article The Problem of Literary Truth in Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s Poetics Paolo Pitari 1,2 1 Department of Linguistics and Comparative Cultural Studies, University Ca’ Foscari, 30123 Venice, Italy; [email protected] 2 Department of English and American Studies, Ludwig-Maximialians-Universität München, D-80799 Munich, Germany Abstract: In contemporary literary theory, Plato is often cited as the original repudiator of literary truth, and Aristotle as he who set down that literature is “imitation,” thus himself involuntarily banning literature from truth. This essay argues that these interpretations adulterate the original arguments of Plato and Aristotle, who both believed in literary truth. We—literary theorists and philosophers of literature—should recognize this and rethink our interpretation of these ancient texts. This will, in turn, lead us to ask better questions about the nature of literary truth and value. Keywords: literary theory; philosophy of literature; literary value; mimesis; interpretation; hermeneutics 1. Premise Today’s commonsense affirms that truth and value belong to the sciences, and that literature has little to offer in these regards. Even many of those who dedicate their lives to literary studies appear to have given up on defending outmoded notions of literary truth and Citation: Pitari, Paolo. 2021. The value. The sciences are truly necessary to humankind. Literature, on the other hand, is a Problem of Literary Truth in Plato’s pastime that may entertain some people, but it is certainly something we could do without. Republic and Aristotle’s Poetics. Literary studies have thus become ever harder to justify. Funding, applications, and Literature 1: 14–23. -

Hart Crane's Queer Modernist Aesthetic

Copyrighted material – 978–1–137–40775–7 © Niall Munro 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6– 10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndsmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978– 1– 137– 40775– 7 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.