Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TCA 049.Pdf (2.027Mb)

Detección de la tendencia local del cambio de la temperatura en México • René Lobato-Sánchez* • Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua, Jiutepec, México *Autor para correspondencia • Miguel Ángel Altamirano-del-Carmen • Consultor, Ciudad de México, México DOI: 10.24850/j-tyca-2017-06-07 Resumen Abstract Lobato-Sánchez, R., & Altamirano-del-Carmen, M. A. Lobato-Sánchez, R., & Altamirano-del-Carmen, M. A. (November- (noviembre-diciembre, 2017). Detección de la tendencia local December, 2017). Detection of local temperature trends in Mexico. del cambio de la temperatura en México. Tecnología y Ciencias Water Technology and Sciences (in Spanish), 8(6), 101-116, del Agua, 8(6), 101-116, DOI: 10.24850/j-tyca-2017-06-07. DOI: 10.24850/j-tyca-2017-06-07. Registros de temperatura indican que tres de cada cuatro Temperature records indicate that three of the four climatic stations estaciones climáticas evaluadas en México señalan un evaluated in Mexico show warming over the years 1950 to 2013, as calentamiento en el periodo 1950-2013, tomando como compared to the period 1961 to 1990 which was used as a baseline. referencia al periodo base 1961-1990. Después de un análisis After a complete analysis of climate records in Mexico, only 112 completo de registros climáticos en México, se determinó que were determined to have met the quality and standards required 101 solamente 112 registros cumplen con la calidad y estándares for the present study. From those, a subset of 20 stations with a requeridos para el presente estudio, de ahí se seleccionó, positive trend were randomly selected, which were representative de forma aleatoria, un subconjunto de 20 estaciones con of urban and rural areas distributed across Mexico. -

Location of Mexico Mexico Is the Second-Largest Country by Size and Population in Latin America

Read and Respond: Location, Climate, and Natural Resources of Mexico and Venezuela Location of Mexico Mexico is the second-largest country by size and population in Latin America. It is the largest Spanish- speaking country in the world. The country is located south of the United States. On the west is the Pacific Ocean, and on the east are the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Mexico’s location between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea allows it the opportunity to trade. There are seven major seaports in Mexico. Oil and other materials from Mexico can be easily shipped around the world to ports along the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Another advantage of Mexico’s location is that it is close to the United States. Because the two countries share a border, trade is easier. Railroads and trucks can be used to ship goods. Mexico’s main trading partner is the United States. Climate of Mexico Mexico has the Sierra Madre Mountains, deserts in the north, tropical beaches, plains, and plateaus. The climate varies according to the location, with some tropical areas receiving more than 40 inches of rain a year. Desert areas in the north remain dry most of the year. Most people live on the Central Plateau of Mexico in the central part of the country. Mexico City, one of the world’s largest cities, is in this region. There is arable (farmable) land in this region, and there is usually enough rain to grow a variety of crops. The region has many manufacturing centers, which provide jobs. -

Impact of Land-Use Changes on the Climate of the Mexico City Region

Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía, UNAM Ernesto Jáuregui ISSN 0188-4611, Núm. 55, 2004, pp. 46-60 Impact of land-use changes on the climate of the Mexico City Region Ernesto Jáuregui* Recibido: 17 de junio de 2004 Aceptado en versión final: 21 de septiembre de 2004 Abstract. It is well established that anthropogenic land-use changes directly affect the atmospheric boundary layer at the mesoscale dimensions. Located in the high lands of Central Mexico, the basin of Mexico (7 500 km2) has undergone a widespread conversion of natural vegetation to urban and agricultural land by deforestation. While the urban extension of the capital city occupied 6% of the basin in 1960, at the end of the twentieth century the urban sprawl had increased considerably to 20% of the total area. This phenomenal growth has impacted on the thermal climate of substantial portions of the basin. In this paper using annual temperature and precipitation data for a 25 year period, an attempt is made to identify interdecadal climate changes. Results show that large areas of the basin have changed toward a warmer drier climate. While afternoon temperatures have increased at a rate of 0.07° C/yr in the suburbs of the city the corresponding area averaged value for the rural sites is somewhat less: 0.06° C/yr. The afternoon temperature increase for the total number of stations used was 0.06° C/yr. The area-averaged minimum temperature increase in suburban stations (3) was 0.15° C/yr while that corresponding to surrounding rural sites was 0.08° C/yr for period 1961-1985. -

The Urban Climate of Mexico City

298 Erdkunde Band XXVII Kawagoe und Shiba einem doppelten Spannungsver der Landflucht ist jedoch aus Kapazitatsgriinden si haltnis ausgesetzt. Als zentripetale Zentralorte und cher. Wanderungszentren sind sie fiir ein weiteres Hinter 2. Hauptanziehungsgebiet werden die grofistadtorien land kaum besonders attraktiv. Die Zentralisations tierten pazifischen Ballungsraume bleiben. Dabei spannungen fiihren iiber sie hinaus direkt zum Haupt wird sich eine weitere zunehmend grofiraumige zentrum. von Ihre Entwicklung wird zentrifugalen der in mit - Ausweitung Ballungszonen Verbindung Kraften der Sie Ballungskerne gesteuert. wachsen, dem Bau neuer Strecken des Schienenschnellver aus - jedoch nicht eigener Kraft sondern als Satelliten. kehrs und neuer Autobahnen abzeichnen. Demgegenuber steht die sich eigenstandig verstar 3. Eine weitere Verstarkung der zwischenstadtischen kende regionale Vormacht der Prafektur-Hauptorte, Wanderungen wird sich auch auf den Austausch die echte Regionalzentren geworden sind. Sobald es zwischen den Ballungsgebieten auswirken. Eine Stu ihnen gelang, konkurrierende Nachbarstadte funktio wird sich nur da vollziehen, wo kla nal zu iiberschichtenund zu iiberholen, fenwanderung grofienmafiig re zentralortliche Hierarchien vorliegen. wuchs und wachst ihr Vorsprung unaufhaltsam wei ter.Das istAomori gegeniiberHirosaki erst halb, Sap 4. Das Prinzip der Wanderungs-Zentralitat aufierhalb erster den poro gegeniiber Asahikawa und Otaru bereits voll ge der Ballungsgebiete wird in Linie grofie ren mit mehr als 300 000 Einwoh lungen. Mentalitat und Wanderungsverhalten der ja Regionalzentren nern wer panischen Bevolkerung unterstutzen den Prozefi der zugute kommen. Kleinere Landeszentren Selbstverstarkung, der das Modell des ?Grofien To den mit der Ausdunnung ihres landlichen Umlandes Prafektur kyo" auf verschiedene ?Klein-Tokyos" im ganzen weiter abnehmen. Die dominierenden werden am starksten weiterwachsen. Land ubertragt. Hauptstadte Es wird abzuwarten sein, in welchem Mafie die zur des neuen Minister D. -

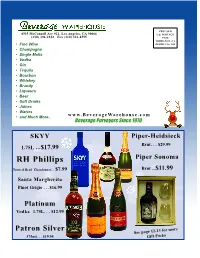

Xmas 2014 Catalog WEB.Pdf

PRST STD 4935 McConnell Ave #21, Los Angeles, CA 90066 U.S. POSTAGE (310) 306-2822 Fax (310) 821-4555 PAID TORRANCE, CA • Fine Wine PERMIT No. 102 • Champagne • Single Malts • Vodka • Gin • Tequila • Bourbon • Whiskey • Brandy • Liqueurs • Beer • Soft Drinks • Juices • Waters • and Much More.. www.BeverageWarehouse.com Beverage Purveyors Since 1970 SKYY Piper-Heidsieck Brut. $29.99 1.75L ...$17.99 RHRH PhillipsPhillips Piper Sonoma Toasted Head Chardonnay. $7.99 Brut ...$11.99 Santa Margherita Pinot Grigio . .$16.99 PlatinumPlatinum Vodka 1.75L. $12.99 PatrPatronon SilverSilver See page 12-13 for more 375ml. $19.95 Gift Packs 2014 Holiday Catalog (310) 306-2822 www.BeverageWarehouse.com Beverage Purveyors Since 1970 All Your Gift Giving Items Spirits pages 12-29 Found Here Over 8,000 Items in Stock Imported and Domestic Beer pages 30-31 (310) 306-2822 www.BeverageWarehouse.com Champagne and NOWNOW ININ STSTOCKOCK Sparkling Wines page 4-6 Tequila nearly 500 in stock Vodka over 300 in stock Cognac & Brandy over 250 in stock Rum over 250 in stock Whiskey over 300 in stock Scotch Blended & S.M. over 200 in stock Open To The Public 7 Days A Week Fine Wine pages 7-11 Over 1,500 Wines Monday - Saturday 9am - 6pm From Around the World Sunday 10am - 5pm We also deliver ... (310) 306-2822 ( Closed Christmas Day & New Year’s Day ) As seen in “West L.A. Shops” WINE SPECTATOR April 30th, 2003 “Award of Distinction” Over 10,000sq. ft. of Beverages ZAGAT SURVEY Non-Alcoholic Products Visit BeverageWarehouse.com From the 405 freeway, take the 90 freeway Westbound toward Marina Del Rey and exit at Culver BL. -

SS6G3 the Student Will Explain the Impact of Location, Climate, Distribution of Natu- Ral Resources, and Population Distribution on Latin America and the Caribbean

SS6G3 The student will explain the impact of location, climate, distribution of natu- ral resources, and population distribution on Latin America and the Caribbean. a. Compare how the location, climate, and natural resources of Mexico and Venezuela affect where people live and how they trade. LOCATION, CLIMATE, AND NATURAL RESOURCES OF MEXICO Location of Mexico Mexico is the second-largest country by size and population in Latin America. It is the largest Spanish-speaking country in the world. The country is located south of the United States. On the west is the Pacific Ocean, and on the east are the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Mexico’s location between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea allows it the opportunity to trade. There are seven major seaports in Mexico. Oil and other materials from Mexico can be easily shipped around the world to ports along the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Another advantage of Mexico’s location is that it is close to the United States. Because the two countries share a border, trade is easier. Railroads and trucks can be used to ship goods. Mexico’s main trading partner is the United States. Climate of Mexico AND CANADA LATIN AMERICA LATIN Mexico has the Sierra Madre Mountains, deserts in the north, tropical beaches, plains, and plateaus. The climate varies according to the location, with some tropical areas receiving more than 40 inches of rain a year. Desert areas in the north remain dry most of the year. Most people live on the Central Plateau of Mexico in the central part of the country. -

Biopolitical Itineraries

BIOPOLITICAL ITINERARIES: MEXICO IN CONTEMPORARY TOURIST LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by RYAN RASHOTTE In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November, 2011 © Ryan Rashotte, 2011 ABSTRACT BIOPOLITICAL ITINERARIES: MEXICO IN CONTEMPORARY TOURIST LITERATURE Ryan Rashotte Advisor: University of Guelph, 2011 Professor Martha Nandorfy This thesis is an investigation of representations of Mexico in twentieth century American and British literature. Drawing on various conceptions of biopolitics and biopower (from Foucault, Agamben and other theorists), I argue that the development of American pleasure tourism post-World War II has definitively transformed the biopolitical climate of Mexico for hosts and guests. Exploring the consolidation in Mexico of various forms of American pleasure tourism (my first chapter); cultures of vice and narco-tourism (my second chapter); and the erotic mixtures of sex and health that mark the beach resort (my third chapter), I posit an uncanny and perverse homology between the biopolitics of American tourists and Mexican labourers and qualify the neocolonial armature that links them together. Writers (from Jack Kerouac to Tennessee Williams) and intellectuals (from ethnobotanist R. Gordon Wasson to second-wave feminist Maryse Holder) have uniquely written contemporary “spaces of exception” in Mexico, have “founded” places where the normalizing discourses, performances of apparatuses of social control (in the U.S.) are made to have little consonance. I contrast the kinds of “lawlessness” and liminality white bodies at leisure and brown bodies at labour encounter and compel in their bare flesh, and investigate the various aesthetic discourses that underwrite the sovereignty and mobility of these bodies in late capitalism. -

Redalyc.The Heat Spells of Mexico City

Investigaciones Geográficas (Mx) ISSN: 0188-4611 [email protected] Instituto de Geografía México Jáuregui, Ernesto The heat spells of Mexico City Investigaciones Geográficas (Mx), núm. 70, diciembre, 2009, pp. 71-76 Instituto de Geografía Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=56912238005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía,UNAM ISSN 0188-4611, Núm. 70, 2009, pp. 71-76 The heat spells of Mexico City Ernesto Jáuregui* Abstract. The warning of urban air has been documented to increase in the last third of the last century when population increase in intensity and area as cities grow (Oke, 1982). As of the city grew from 8.5 to 18.5 million (CONAPO, 2000). the cities grow the so called “heat island” tends to increase During this time the average urban/rural contrast grew the risk of more frequent heat waves as well as their impacts considerably from about 6° C to 10° C (Jáuregui, 1986). (IPCC, 2001). Threshold values to define a heat wave vary While these heat waves may be considered as “mild”they geographically. For the case of Mexico City located in a receive attention from the media and prompt actions by high inland valley in the tropics, values above 30° C (daily the population to relieve the heat stress. Application of maximum observed for three or more consecutive days and heat indices based on the human energy balance (PET and 25° C or more as mean temperature) have been adopted PMV) result in moderate to strong heat stress during these to define the phenomenon. -

Archival Explorations of Climate Variability and Social Vulnerability in Colonial Mexico

Climatic Change (2007) 83:9–38 DOI 10.1007/s10584-006-9125-3 Archival explorations of climate variability and social vulnerability in colonial Mexico Georgina H. Endfield Received: 27 September 2005 / Accepted: 3 April 2006 / Published online: 8 March 2007 C Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2007 Abstract In this paper, unpublished archival documentary sources are used to explore the vulnerability to–and implications of–climatic variability and extreme weather events in colo- nial Mexico. Attention focuses on three regions covering a variety of environmental, social, economic, and political contexts and histories and located at key points along a north-south rainfall gradient: Chihuahua in the arid north, Oaxaca in the wetter south and Guanajuato located in the central Mexican highlands. A number of themes are considered. First, the significance of successive, prolonged, or combined climate events as triggers of agrarian crisis. Second, a case study demonstrating the national and regional impacts of a particu- larly devastating climate induced famine, culminating with the so-called ‘Year of Hunger’ between 1785 and 1786, is presented. The way in which social networks and community engagement were rallied as a means of fortifying social resilience to this and other crises will be highlighted. Third, the impacts of selected historical flood events are explored in order to highlight how the degree of impact of a flood was a function of public expectation, preparedness and also the particular socio-economic and environmental context in which the event took place. An overview of the spatial and temporal variations in vulnerability and resilience to climatic variability and extreme weather events in colonial Mexico is then provided, considering those recorded events that could potentially relate to broader scale, possibly global, climate changes. -

La Cuenca Del Río Conchos: Una Mirada Desde Las Ciencias Ante El Cambio

Durante las últimas décadas, diversos estudios han analizado la problemática de los potenciales efectos LA CUENCA DEL RÍO CONCHOS: del cambio climático en zonas de estrés hídrico tal como se observan ya en la zona norte del país, en UNA MIRADA DESDE LAS CIENCIAS particular en la cuenca del Río Conchos. ANTE EL CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO Sin embargo, poco se ha discutido sobre los cambios ya registrados en el clima actual y su influencia en los aspectos socio-ambientales de una región determinada. En este sentido, la presente obra analiza varios de los aspectos climáticos y su relación con el medio ambiente y la sociedad, a través de diferentes técnicas numéricas y canales de información, para una mejor comprensión de las implicaciones del cambio climático y su inherente factor multidisciplinario. Martín José Montero Martínez Óscar Fidencio Ibáñez Hernández Coordinadores LA CUENCA DEL RÍO CONCHOS: UNA MIRADA DESDE LAS CIENCIAS ANTE EL CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO LA CUENCA DEL RÍO CONCHOS: LA CUENCA DEL RÍO CONCHOS: UNA MIRADA DESDE LAS CIENCIAS ANTE EL CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO Martín José Montero Martínez Oscar Fidencio Ibáñez Hernández Coordinadores México, 2017 553.7 Montero, Martín (coordinador) M44 La cuenca del río Conchos: una mirada desde las ciencias ante el cambio climático / Martín José Montero Martínez y Oscar Fidencio Ibáñez Hernández, coordinadores. -- Jiutepec, Mor. : Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua, ©2017. 267 p. ISBN 978-607-9368-89-0 (versión impresa). ISBN 978-607-9368-90-0 (versión digital). 1. Cuencas 2. Cambio climático 3. Río Conchos Coordinación editorial: Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua, México. Primera edición: 2017 Instituto Mexicano de Tecnología del Agua Paseo Cuauhnáhuac 8532 62550 Progreso, Jiutepec, Morelos MÉXICO www.imta.gob.mx Se permite su reproducción parcial o total, por cualquier medio, mecánico, electrónico, de fotocopias, térmico u otros, sin permiso de los editores, siempre y cuando se mencione la fuente. -

Winter-Spring Precipitation Reconstructions from Tree Rings for Northeast Mexico

Climatic Change DOI 10.1007/s10584-006-9144-0 Winter-spring precipitation reconstructions from tree rings for northeast Mexico Jose Villanueva-Diaz · David W. Stahle · Brian H. Luckman · Julian Cerano-Paredes · Mathew D. Therrell · Malcom K. Cleaveland · Eladio Cornejo-Oviedo Received: 3 October 2005 / Accepted: 9 May 2006 C Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2007 Abstract The understanding of historic hydroclimatic variability is basic for planning proper management of limited water resources in northeastern Mexico. The objective of this study was to develop a network of tree-ring chronologies to reconstruct hydroclimate variability in northeastern Mexico and to analyze the influence of large-scale circulation patterns, such as ENSO. Precipitation sensitive tree-ring chronologies of Douglas-fir were developed in mountain ranges of the Sierra Madre Oriental and used to produce winter- spring precipitation reconstructions for central and southern Nuevo Leon, and southeast- ern Coahuila. The seasonal winter-spring precipitation reconstructions are 342 years long (1659–2001) for Saltillo, Coahuila and 602 years long (1400–2002) for central and south- ern Nuevo Leon. Both reconstructions show droughts in the 1810s, 1870s, 1890s, 1910s, and 1970s, and wet periods in the 1770s, 1930s, 1960s, and 1980s. Prior to 1800s the reconstructions are less similar. The impact of ENSO in northeastern Mexico (as mea- sured by the Tropical Rainfall Index) indicated long-term instability of the Pacific equa- torial teleconnection. Atmospheric circulation systems coming from higher latitudes (cold J. Villanueva-Diaz () · J. Cerano-Paredes Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales y Agropecuarias, Centro Nacional de Investigaci´on Disciplinarioa en Relaci´on Agua, Suelo, Planta, Km 6.5 Margen Derecha del Canal Sacramento, Gomez Palacio, Durango, 35140, Mex. -

Potencial De Investigación 17

Inventario de la investigación científica y tecnológica en materia de cambio climático en México, 2005. (Febrero de 2006) (Mayo 2006) Dr. Omar Romero Hernández (ITAM) Dr. Sergio Romero Hernández (ITAM) 1 ÍNDICE 1. ANTECEDENTES 4 2. OBJETIVOS 5 3. METODOLOGÍA 6 3.1 Evaluación informática del inventario existente 6 3.2 Desarrollo de la base de datos 8 3.3 Actualización y verificación de datos 9 3.4 Identificación de nuevos contactos 11 3.5 Bases de Datos resultantes 14 4. RESULTADOS 17 4.1 Potencial de investigación 17 4.2 Distribución geográfica 19 4.2.1 Entidades con mayor número de contactos 21 4.2.2 Entidades con menor número de contactos 22 4.3 Análisis de temas abordados 25 4.3.1 Líneas y Temas más abordados 32 4.3.2 Líneas y Temas no abordados o menos abordados 32 4.4 Financiamiento 34 4.4.1 Estado actual 36 4.4.4 Alternativas para el desarrollo de proyectos 45 ANEXO A. BASE DE DATOS ACTUALIZADA 49 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS Los autores de este trabajo desean agradecer al Dr. Edmundo de Alba por sus comentarios y sugerencias durante el inicio de este proyecto y durante la presentación del mismo ante el Comité Técnico Asesor (CAT) el día 27 de enero de 2006. Asimismo, deseamos agradecer al personal del Instituto Nacional de Ecología (INE) y del Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD) por su apoyo técnico y administrativo en la elaboración de este trabajo. Nuestro agradecimiento es a todos ellos y especialmente a la Biol. Julia Martínez, a la M.