Porsche at the Monte Carlo Rally

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

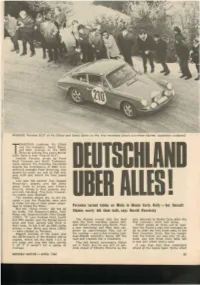

1968 Monte Carlo Rally – First Victory in the 911

1968 Monte Carlo Rally – first victory in the 911 The Porsche 911 took three consecutive wins in the Monte Carlo Rally, with Vic Elford and David Stone delivering the first of these victories in 1968. In an ideal development for Porsche, the 1968 Monte Carlo Rally was the first to be subject to new rules that removed restrictions relating to cubic capacity classes and the use of professional and amateur drivers. The system applied as of that year boiled down to a single maxim: fastest car wins! Another factor that was markedly different to previous years was the weather. The 37th Monte Carlo Rally was held in almost spring-like temperatures, with these mild conditions extending up into the mountains. The teams demanded racing tyres, but the available stocks proved insufficient. This led to additional tyres featuring a soft mixture, little tread and no spikes being flown in by the tyre manufacturers via Nice and transported to the special tests. While the French driver Gérard Larrousse dominated the early stages of this edition of the Monte Carlo Rally in his Renault Alpine 1300, Vic Elford and David Stone bided their time in the 911 S 2.0 and waited for an opening. The ‘night of the long knives’, which was open to the sixty fastest teams, initially saw Larrousse further extend his lead before Elford hit back. Completing the special test at the Col de la Couillole nearly a minute faster than the Alpine, he duly raced into the lead. The final tests then saw the top drivers take even greater risks. -

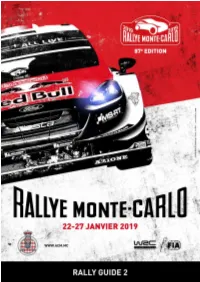

87E RALLYE AUTOMOBILE MONTE-CARLO

87e RALLYE AUTOMOBILE MONTE-CARLO 22 - 27 JANUARY 2019 organised by THE AUTOMOBILE CLUB DE MONACO under the High Patronage of THEIR SERENE HIGHNESSES THE PRINCE AND PRINCESS OF MONACO with the support of THE PRINCELY GOVERNMENT THE MUNICIPALITY OF MONACO THE SOCIETE DES BAINS DE MER THE MUNICIPALITY OF GAP THE FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE L’AUTOMOBILE THE FEDERATION FRANCAISE DU SPORT AUTOMOBILE This document has no regulatory power. For information only. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 3 2. ORGANISATION CONTACT DETAILS ..................................................................................... 4 3. PROGRAMME ......................................................................................................................... 6 4. ENTRIES ................................................................................................................................ 11 5. SERVICE PARK ...................................................................................................................... 14 6. TWO-WAY RADIOS .............................................................................................................. 15 7. FUEL / TYRES ........................................................................................................................ 16 8. IMPORT OF VEHICLES AND SPARE PARTS ........................................................................... 16 9. HELICOPTERS ...................................................................................................................... -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized IN TiUS ISSUE The Great American Motor Rallye •...............•... Meet a Foreigner . .. Christma~ Cocktail Party Pictures. ............... Public Disclosure Authorized The following statement was made by Mr. Andrew N. Overby at the last Executive Directors' meeting in 1955. We think his words are most fitting as a thought for the New Year. "Mr. Chairman: "This, I believe. will be the last meeting of the year. and I think it is appropriate at this time not only to extend to the management and staff of the Bank the Board's Christmas greetings. but also their deep appreciation. of the work and able and efficient discharge of duty on behalf of the staff• . They wish also to pay tribute to the leadership of the management of the Bank which has taken us through another difficult year and. we think, without running afoul of too many rocks, and has taken us into some new and perhaps even interesting horizons lying ahead of us. "So with those words. we expres~ our appreciation, as well as our Christmas greetings to you and all the members of the staff, sir." CHRISTMAS CARDS RE<:;EIVED BY THE BANK, 1955 The First National Ciiy Bank of Caisse d'Epargne de L 'Etat, New York Luxembourg Amsterdamsche Bank The Workers' Bank Ltd., Israel Governor of the Bank of Greece Landsbanki Islands La Asociacion Mexicana de Caminos Central Hidroelectrica del Rio Federal Reserve Bank of New York Anchicaya, Limitada,. Colombia Bank of the Ryukyus Comptoir National d'Escompte de Banque de France Paris Industrial Development Bank of The Trust Company of Cuba Turkey Central Office of Information, Malta Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij. -

171024-Three-ŠKODA-Crews-In-WRC-2-At-Wales

ŠKODA MOTORSPORT PRESS RELEASE Page 1 of 4 Three ŠKODA crews in WRC 2 at Wales Rally GB Veiby and Nordgren alongside champion Tidemand › New WRC 2 Champions Pontus Tidemand and co-driver Jonas Andersson lead the three cars of the ŠKODA factory squad at the penultimate round of World Rally Championship › Norwegian youngsters Ole Christian Veiby/Stig Rune Skjaermœn and Finnish shooting stars Juuso Nordgren/Tapio Suominen competing in a ŠKODA FABIA R5 as well › ŠKODA Motorsport boss Michal Hrabánek: “Running three factory cars for the second time in 2017 demonstrate our outstanding performance in WRC 2.” Mladá Boleslav, 24 October 2017 – ŠKODA Motorsport will compete at the upcoming Wales Rally GB (26/10–29/10/2017) with three ŠKODA FABIA R5 cars driven by the new WRC 2 Champions Pontus Tidemand/Jonas Andersson WRC 2, Norwegians Ole Christian Veiby/Stig Rune Skjaermœn and Juuso Nordgren from Finland, joined by co-driver Tapio Suominen. While experienced Tidemand is aiming to score his fifth 2017 victory in WRC 2 category, youngsters Veiby and Nordgren want to demonstrate their skills behind the steering wheel of the works ŠKODA FABIA R5. “After Monte Carlo Rally for the second time in 2017 we are running three works teams in a round of the World Rally Championship. Having prematurely won the WRC 2 Championship with Pontus Tidemand and Jonas Andersson, also having secured the FIA WRC 2 Championship for Teams, I am really looking forward to the performance of our three teams,” explains ŠKODA Motorsport boss Michal Hrabánek. Pontus Tidemand and co-driver Jonas Andersson won the WRC 2 category already in Sweden, Mexico, Argentina and Portugal. -

History of the Alpine Brand

HISTORY OF THE ALPINE BRAND Alpine is the story of a brand, but it is also the story of men before being, tomorrow, the story of a renewal. CONTENTS I. A "RENAULT" FAMILY II. JEAN RÉDÉLÉ, RACING CHAMPION III. THE CREATION OF ALPINE IV. FROM ALPINE TO ALPINE-RENAULT V. AN INNOVATIVE EXPORT POLICY VI. ALPINE’S REBIRTH VII. MOTORSPORT, ALPINE’S DNA VIII. ALPINE: A HISTORY OF MEN IX. ALPINE PRODUCTION IN FIGURES X. SOME TITLES WON BY ALPIN 1 Confidential C I. A RENAULT ‘FAMILY’ Jean Rédélé was the first-born son of Madeleine Prieur and Emile Rédélé, a Renault dealer based in Dieppe and a former mechanic of Ferenc Szisz – the first Renault Frères ‘factory driver’, winner of the Grand Prix de la Sarthe in 1906 at Le Mans and runner-up in the Grand Prix de l'A.C.F. in Dieppe in 1907. Louis Renault himself had hired Emile Rédélé right at the beginning of the 20th Century. At the end of the First World War, at the request of Louis Renault, the young Emile Rédélé settled in Dieppe and opened a Renault dealership there in rue Thiers. Two years later, Jean-Emile- Amédée Rédélé was born on May 17, 1922. After completing his studies in Normandy, Jean Rédélé took his Baccalauréat exam during the Second World War and came into contact with people as diverse as Antoine Blondin, Gérard Philipe and Edmond de Rothschild. He chose to be a sub-prefect before settling on a career direction and enrolling at the H.E.C. -

Porsches Turnea Tables on Minis in Monte Carlo Rally - but Renault but the "Flying Bricks" Did Not Do Too Badly

WINNING Porsche 911T of Vic Elford and David Stone on the final mountain circuit run where Alpines' opposition collapsed. ENACIOUS Londoner Vic Elford and his navigator, David Stone, got their revenge on the BMC Minis by winning this year's Monte TCarlo Rally in their Porsche 911 T. Another Porsche, driven by Finns Pauli Toivonen and Martti Tiukkanen, came second. The Porsches triumphed despite the incantations of BMC com petitions manager Peter Browning, who prayed for snow, ice, and all that slip pery stuff just before the final speed trials. Last year the weather man heeded Browning's prayers and the Minis swept home to victory over Elford's Porsche, thanks to their superior slip and-slide handling. This time, however, the tables were reversed. The weather stayed dry, so did the roads - and the Porsches were able to make full use of their power advan tage to topple the Minis. Porsches turnea tables on Minis in Monte Carlo Rally - but Renault But the "flying bricks" did not do too badly. The Aaltonen/Liddon, Fall/ Alpines nearly did them both, says Harold Dvoretsky Wood and Hopkins/Crellin Mini-Cooper 1293cc "S" cars finished third, fourth and fifth overall, won the Equipe teams The Alpines moved into the lead cars returned to Monte Carlo after the prize and first, second and third in after the third mid-Rally special test, first mountain climb test series. their class. To top it off, all BMC works with Elford's Porsche lying fourth_ Then Elford pulled all stops out to over entries - four Minis and three 1800s a dud distributor put their lead car, haul the Alpine's lead and managed to - were classed as finishers. -

Eligible Cars

Rallye Monte-Carlo Historique Side 1 af 3 Eligible Cars Models which took part in a Monte-Carlo Rally between 1955 and 1977 (non exhaustive list) z ABARTH : 750 - 1000 - 850TC - 1000TC z A.C. : Ace - Aceca - Bristol z ALFA-ROMEO : 1900, TI, Super, coupéSS, SZ - Giulietta, TI, Sprint, Spider, SZ - Giulia : Super, TI, TISuper, GT, GTV, GTA, GTAM - 1300GT - 1750 : GT, Spider - 2000, GTV - AlfasudTI - AlfettaGT z ALLARD : P2 z ALPINE : A106 - A108 z ALPINE-RENAULT : A110, Bulgaralpine - A310 z ALVIS : 3L. z ARMSTRONG-SIDDELEY : Sapphire z ASTON-MARTIN : DB2 - DB2/4 - DBMkIII - DB4 z AUDI : 70 - Super90 - 100S - 80, S, GT z AUSTIN : A30 - A50 - A90 - A35 - A95 - A105 - A99 - A110 - Taxi (->61) - A40 - 1100Mk1 - Authi - 1800, S - Maxi - Mini, Cooper, CooperS, 1275GT (->73) z AUSTIN-HEALEY : Sprite, Sebring - 100/6 - 3000 z AUTOBIANCHI : Primula - A112, Abarth z AUTO-UNION / DKW : 900/3=6 - 1000, S, coupé - Junior - F12 z BERKELEY : B90 z BMW : 501 - 502 - 503 - 700, S - 1500 - 1800, TI - 2000, TI - 1600, TI, 2 - 2002, TI, TII, Turbo - 2500 - 2800, CS z BOND : Equipe z BORGWARD : Isabella, TS z BRISSONNEAU-LOTZ : 4CV z BRISTOL : 403 - 405 z CHEVROLET : Impala (->66) - Camaro (->73) z CITROEN : 11B - 15/6 - ID, DS19 - 2CV (->59) - Ami6 - DS21, 23 - SM - GS - Dyane6 z DAF : Daffodil - 44 - 55 - 66 z DAIMLER : Conquest - Century - Consort z DATSUN / NISSAN : Bluebird1300, 1600, SSS - 2000 - Sunny - 240Z - Cherry - Violet z DB PANHARD : CoachHBR5 z DENZEL : 1300 z DE TOMASO : Pantera z FACEL VEGA : Facellia z FAIRTHORPE : Electron z FERRARI : 250GTBoano -

Mini Wrc Team

MINI WRC TEAM Media Information MINI WRC TEAM. Media Information MINI WRC TEAM Media Information Contents. The legend returns: MINI lines up in the FIA WRC in 2011. Page 3 Ian Robertson: “MINI is returning to its roots.” Page 5 Dr Wolfgang Armbrecht: “For us 2011 is a learning year.” Page 7 Prodrive – a strong partner for MINI's comeback to rallying. Page 9 MINI WRC driver Kris Meeke in profile. Page 11 MINI WRC driver Daniel “Dani” Sordo in profile. Page 13 Meticulous development work the key to success. Page 15 The MINI WRC: Technical specifications. Page 16 The benchmark in the 1960s: the MINI Cooper S. Page 18 Rauno Aaltonen: “Every child must first be nurtured.” Page 20 Historic victories: MINI in international motorsport. Page 21 Press Contact. Page 22 MINI WRC TEAM Media Information The legend returns: MINI lines up in the FIA WRC in 2011. Munich, 2nd February 2011. The countdown is on to the return of MINI on the international motorsport stage. This season, the new MINI WRC Team will compete at selected rounds in the FIA World Rally Championship (WRC). The aim is to gain valuable experience, in order to be perfectly prepared for the complete 2012 World Championship season. The MINI WRC has been developed by Prodrive, based on the MINI Countryman. It is equipped with a 1.6-litre turbo engine derived from the MINI production models, which was developed by BMW Motorsport for use in series run according to FIA Super2000 regulations, including the World Touring Car Championship. As well as its works involvement with the MINI WRC Team, Prodrive is supplying the customer car to private rally teams, who will also run the car in the S2000 class of the World Rally Championship. -

Stars of the Stage

STARS OF THE STAGE When the World Rally Championship first began in 1973, only the car manufacturers fought for a crown; it wasn’t until 1979 that the drivers were recognised with their own world title. They soon made up for lost time, however, and over the past four decades the WRC has been a constant source of drama, heroism and displays of unbelievable skill. So as the Festival celebrates 40 years of the World Rally Drivers’ Championship this weekend, we remember some of those who have fought for and won the sport’s greatest prize STORY BY ANGUS FRAZER Left: Petter Solberg and co-driver Phil Mills celebrate victory in the 2002 Rally GB. Right: Sébastien Ogier powers his Citroën to third in the 2019 Argentine Rally Rallying’s first World Champion proved that while sublime skill and dogged determination are both prerequisites for victory, ruthlessness Björn is not. Described by those who knew him as a true gentleman (and sometimes as a teddy bear), the late Björn Waldegård won the inaugural World Rally Drivers’ Championship in 1979 (prior to that, the competition had Waldegård been held for two years as an FIA ‘Cup for Drivers’, won by Sandro Munari in 1977 and Markku Alén in 1978). All through that season, Waldegård battled Hannu Mikkola, his team-mate not just at Ford in the pace-setting Escort RS but also at Mercedes-Benz. The German company had 1979 hired the duo to pilot the powerful if unwieldy 5.0-litre V8 automatic 450SLC Coupé on the Safari and Ivory Coast events. -

XXIV Rallye Automobile Monte-Carlo

sections will be taken from the time taken to cover that particular section. To determine the classification, the rally will conclude with a speed test on the Monte Carlo G.P. circuit over five laps, the first of which has to be covered in a minimum time of 3 mins. 26 secs. from a standing start. Performance will be worked out from the fastest lap accomplished, and the following formula will be applied: Speed equals time taken, multiplied by engine capacity, over engine capacity plus 150. XXIV RALLYE AUTOMOBILE MONTE-CARLO On Monday Nearly 400 Crews Leave Starting Controls at Glasgow, Lisbon, Athens, Palermo, Oslo, Stockholm, Munich and Monte Carlo for Start of Big Winter Event ON Monday, 18th January, Blythswood Athens, are “No. 1” in the list of Square, Glasgow will be a seething entries. Sheila van Damm and Leslie AUTOSPORT mass of people eager to watch the start Johnson are also Sunbearn-Talbot Rally Information Service of the 14th Monte Carlo Rally. First car entries. Trials men Cyril Corbishley is due to leave the starting control and Doe. Hardmari are amongst the LTHOUGH the Meteorological organized by the Royal Scottish Auto- Daimler drivers, whilst George Murray- AOffice of the Air Ministry is mobile Club at 1.09 p.m., and thereafter Frame is in a Humber. reluctant to indulge in long-range entrants will leave at minute intervals Runner-up in the 1953 Tulip Rally, forecasts of more that 48 hours in on their 2,040 miles journey. Bill Banks has entered an Alvis, whilst advance, it has been possible to gather First car at the Llandrindod control “Pathfinder” Bennett and Mike Couper details of what weather can be expected is due off at 11.28 p.m., and from have Armstrong Siddeley Sapphires. -

KING of the ROAD Racing Legend Walter Röhrl Warms to the New 911 As He Takes Us Along on the Key Stage of the Monte Carlo Rally

CHRISTOPHORUS | 353 CHRISTOPHORUS | 353 KING OF THE ROAD Racing legend Walter Röhrl warms to the new 911 as he takes us along on the key stage of the Monte Carlo Rally. Th e Col de Turini gives driver and car a chance to shine. By David Staretz Photos by Bernd Kammerer e rsch Foto o lin P k 72 73 CHRISTOPHORUS | 353 CHRISTOPHORUS | 353 KING OF THE ROAD Tunnel of love: A new take on speed within the limits of Monegasque law. limb Mount Everest with Reinhold Messner, go to a red-carpet event with Karl Lagerfeld or Angelina Jolie, have dinner with Paul Bocuse, C play 18 holes with Tiger Woods … those scenarios all sound pretty special. But I can add one that’s even more exciting (i.e., faster): a trip up the Col de Turini in the new 911 with Walter Röhrl. Th e Col de Turini is a pass in the Massif du Mercantour in the French Maritime Alps. But it’s much more than just a geographical location—it elicits a wealth of associations for racing buff s. No one could tell more authentically about this special leg of the Monte Carlo Rally than Röhrl, who won the rally four times. “Up to 30,000 people would be waiting for us up at the top of the pass. You would come speeding up over the last hump toward the pass and suddenly you’d be blinded by a wall of camera fl ashes. And the next second, you’d go hur- tling down the next side again on icy roads.” In the so-called Night of Turini—also known as the “Night of the Long Knives” due to the strong high-beam lights cutting through the night—in which race-car drivers have to navigate the Turini up to three times, the pressure on the lead driver is enormous. -

World Ofrally

The leading motorsport technology publication since 1990 Special digital edition • July 2016 • www.racecar-engineering.com World of rally E [email protected] CONTENTS Contents 4 HYUNDAI 20 DANNY i20 R5 under the spotlights Slip angles on gravel 12 PEUGEOT 2008 DKR 26 RALLY 2017 Rally raid Dakar winner What’s that coming over the hill? 18 ABARTH Produced by Andrew Cotton, Sam Collins, Lightweight rallying Mike Breslin and Dave Oswald RALLY 2016 DIGITAL SPECIAL 3 R5 - HYUNDAI I20 4 RALLY 2016 DIGITAL SPECIAL he FIA’s car and component cost-capped R5 regulations define competition cars which may appear ostensibly similar to World Rally Cars, but these machines are in fact Tone tier down from the WRC top level. They do have a similar powertrain layout to the current WRCs, with Hy’ Five passive front and rear differentials and no centre diff Hyundai’s i20 R5 is the latest in in their four-wheel-drive system. They can also have a turbocharged engine up to 1620cc, but this must a string of customer sport rally be based on a manufacturer’s production engine – hence WRC-style ‘Global’ engines are not allowed. The cars to roll out of manufacturers’ turbocharger must also be from a production car, while just five forward gear ratios are allowed with one final workshops. But will it be able take drive ratio. Suspension must be MacPherson strut, and the fight to M-Sport and Skoda all four uprights must be identical. Beyond these headline points, the R5 regulations out on the stages? are actually quite complex, incorporating maximum prices for components and assemblies, aimed at By MARTIN SHARP producing a highest price of €180,000 for a new asphalt specification R5 car before tax and registration costs – although FIA Appendix J still allows for free options in the areas of seats, batteries and the like.