And the Beat Goes On: Popular Billboard Song Beats Per Minute and Key Signatures Vary with Social and Economic Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An App to Find Useful Glissandos on a Pedal Harp by Bill Ooms

HarpPedals An app to find useful glissandos on a pedal harp by Bill Ooms Introduction: For many years, harpists have relied on the excellent book “A Harpist’s Survival Guide to Glisses” by Kathy Bundock Moore. But if you are like me, you don’t always carry all of your books with you. Many of us now keep our music on an iPad®, so it would be convenient to have this information readily available on our tablet. For those of us who don’t use a tablet for our music, we may at least have an iPhone®1 with us. The goal of this app is to provide a quick and easy way to find the various pedal settings for commonly used glissandos in any key. Additionally, it would be nice to find pedal positions that produce a gliss for common chords (when possible). Device requirements: The application requires an iPhone or iPad running iOS 11.0 or higher. Devices with smaller screens will not provide enough space. The following devices are recommended: iPhone 7, 7Plus, 8, 8Plus, X iPad 9.7-inch, 10.5-inch, 12.9-inch Set the pedals with your finger: In the upper window, you can set the pedal positions by tapping the upper, middle, or lower position for flat, natural, and sharp pedal position. The scale or chord represented by the pedal position is shown in the list below the pedals (to the right side). Many pedal positions do not form a chord or scale, so this window may be blank. Often, there are several alternate combinations that can give the same notes. -

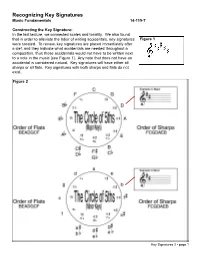

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T Constructing the Key Signature: In the last lecture, we connected scales and tonality. We also found that in order to alleviate the labor of writing accidentals, key signatures Figure 1 were created. To review, key signatures are placed immediately after a clef, and they indicate what accidentals are needed throughout a composition, thus those accidentals would not have to be written next to a note in the music [see Figure 1]. Any note that does not have an accidental is considered natural. Key signatures will have either all sharps or all flats. Key signatures with both sharps and flats do not exist. Figure 2 Key Signatures 2 - page 1 The Circle of 5ths: One of the easiest ways of recognizing key signatures is by using the circle of 5ths [see Figure 2]. To begin, we must simply memorize the key signature without any flats or sharps. For a major key, this is C-major and for a minor key, A-minor. After that, we can figure out the key signature by following the diagram in Figure 2. By adding one sharp, the key signature moves up a perfect 5th from what preceded it. Therefore, since C-major has not sharps or flats, by adding one sharp to the key signa- ture, we find G-major (G is a perfect 5th above C). You can see this by moving clockwise around the circle of 5ths. For key signatures with flats, we move counter-clockwise around the circle. Since we are moving “backwards,” it makes sense that by adding one flat, the key signature is a perfect 5th below from what preceded it. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

Universi^ Micfdmlms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality o f the material submitted. The following explanation o f techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image o f the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Key and Mode in Seventeenth- Century Music Theory Books

204 KEY AND MODE IN SEVENTEENTH- One of the more remarkable cultural phenomena of modern times is the emergence of a generally accepted musico-syn- tactical system (a musical "language") known, among other ways, as the "common practice of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries," or as the "major/minor system of harmony," or as "tonal [as opposed to modal] harmony. " While twentieth-cen- tury composers have sought new ways to structure music, in- terest in the major/minor system continues undiminished owing to a variety of reasons, among them the facts that the bulk of present day concert repertoire stems from the common prac- tice period, and that theories relevant originally to music of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries have been profitably extended to more recent music. 205 CENTURY MUSIC THEORY BOOKS WALTER ATCHERSON Much has been written concerning the major/minor system. By far the most words have been expended in attempts to codify the syntax of major/minor and make it into a workable method of teaching composition. Numerous music theory text books of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries fall into this cate- gory. Another category of writing concerning the major/minor system consists of those efforts to set forth philosophical, mathematical, or acoustical explanations of major/minor har- mony; this category often overlaps the first, as it does already in Jean-Philippe Rameau's TRAITE DE L'HARMONIE (1722). In the twentieth century the major/minor system has ceased to serve as a basis for composition instruction, and the search 206 for philosophical, mathematical, and acoustical explanations has proved unrewarding. -

Phd Thesis, University of Helsinki, Department of Computer Science, November 2000

5 Quantisation hythm together with melody is one of the basic elements in music. According to Longuet-Higgins ([LH76]) human listeners are much more sensitive to the perception of rhythm than to the R perception of melody or pitch related features. Usually it is easier for trained and untrained listeners as well as for musicians to transcribe a rhythm, than details about heard intervals, harmonic changes or absolute pitch. “The term rhythm refers to the general sense of movement in time that characterizes our experience of music (Apel, 1972). Rhythm often refers to the organization of events in time, such that they combine perceptually into groups or induce a sense of meter (Cooper & Meyer, 1960; Lerdahl & Jackendoff, 1983). In this sense, rhythm is not an objective property of music, it is an experience that has both objective and subjective components. The experience of rhythm arises from the interaction of the various materials of music – pitch, intensity, timbre, and so forth – within the individual listener.” [LK94] In general the task of transcribing the rhythm of a performance is different from the previously described beat tracking or tempo detection issue. For estimating a tempo profile it is sufficient to infer score time positions for a set of dedicated anchor notes (i.e., beats respectively clicks), for the rhythm transcription task score time positions and durations for all performance notes must be inferred. Because the possible time positions in a score are specified as fractions using a rather small set of possible denominators, a score represents a grid of discrete time positions. The resolution of the grid is context and style dependent, common scores often uses only a resolution of 1/16th notes but higher resolutions (in most cases binary) or non-standard resolutions for arbitrary tuplets can always occur and might also be correct. -

Key Signatures Meters Tempo Clefs and Transpositions Position Work

The composition criteria for MSHSAA sight reading selections were revised in 2013-14. As a result, the committee determined that it would be beneficial to music directors throughout the state to have this criterion available to assist in preparations for sight reading. With this information in hand, directors will have a better understanding of the difficulty of the selection that will be used and will know what to expect in regard to rhythms, ranges, time signatures, etc. Key Signatures Key Signatures will be limited to the following: C, G, D, F, Bb major and relative natural minors. There should be at least one key signature change per piece. Meters Meters will be limited to the following: 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, Cut Time, 6/8 Tempo Tempi will be no slower than 72 beats per minute and no faster than 120 beats per minute. For continuous pieces, there will be at least one tempo change, but no more than two. Clefs and Transpositions Viola can have limited use of treble clef. Cello can have limited use of tenor clef. Position Work for Strings 3rd position and minimal use of 5th position may be used in the violin 1 part only. Minimal 3rd position work may be used in the violin 2 and viola parts. Half, 2nd, 3rd and 4th position work may be used in the cello part. Half position to the fourth position work may be used in the bass part. Divisi Limited use of divisi parts may be written. Repeats 1st and 2nd endings may be used. -

B.A.Western Music School of Music and Fine Arts

B.A.Western Music Curriculum and Syllabus (Based on Choice based Credit System) Effective from the Academic Year 2018-2019 School of Music and Fine Arts PROGRAM EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES (PEO) PEO1: Learn the fundamentals of the performance aspect of Western Classical Karnatic Music from the basics to an advanced level in a gradual manner. PEO2: Learn the theoretical concepts of Western Classical music simultaneously along with honing practical skill PEO3: Understand the historical evolution of Western Classical music through the various eras. PEO4: Develop an inquisitive mind to pursue further higher study and research in the field of Classical Art and publish research findings and innovations in seminars and journals. PEO5: Develop analytical, critical and innovative thinking skills, leadership qualities, and good attitude well prepared for lifelong learning and service to World Culture and Heritage. PROGRAM OUTCOME (PO) PO1: Understanding essentials of a performing art: Learning the rudiments of a Classical art and the various elements that go into the presentation of such an art. PO2: Developing theoretical knowledge: Learning the theory that goes behind the practice of a performing art supplements the learner to become a holistic practioner. PO3: Learning History and Culture: The contribution and patronage of various establishments, the background and evolution of Art. PO4: Allied Art forms: An overview of allied fields of art and exposure to World Music. PO5: Modern trends: Understanding the modern trends in Classical Arts and the contribution of revolutionaries of this century. PO6: Contribution to society: Applying knowledge learnt to teach students of future generations . PO7: Research and Further study: Encouraging further study and research into the field of Classical Art with focus on interdisciplinary study impacting society at large. -

Lecture Notes on Transposition and Reading an Orchestral Score

Lecture Notes on Transposition and Reading an Orchestral Score John Paul Ito Orchestral Scores The amount of information presented in an orchestral score can seem daunting, but a few simple things about the way the score is arranged can make it much more manageable. The instruments are grouped by families, in the following order: Woodwinds Horns Brass Percussion [Soloists, Singers] Strings Within each family, instruments are grouped by type, ordered with the higher instrument types higher within the family: Woodwinds: Flutes Oboes Clarinets Bassoons Brass: Trumpets Trombones Tubas Strings: Violin 1 Violin 2 Viola Cello Bass Notes on Transposition – © 2010 John Paul Ito 2 Similarly, individual instruments within an instrument type are ordered from high to low: Flutes Piccolo Flute Alto Flute Oboes Oboe Cor anglais Clarinets Eb Clarinet Clarinet Bass Clarinet Note that grouping by instrument type first means that the score will not reflect a consistent progression from high to low within instrument families. For example, among the woodwinds, the cor anglais will appear above the Eb clarinet, even though the Eb clarinet has a higher register. For the purposes of harmonic analysis, it is very convenient that scores are laid out with the strings on the bottom. This reflects an 18th-century concept of orchestration, in which the strings served as a foundation, with winds and brass added for extra color. Even into the 19th century, it remains true that all of the information needed for harmonic analysis is found in the strings, at the bottom of the score. This makes analysis easier, because string instruments are not transposing instruments. -

Pitch Notation

Pitch Notation Collection Editor: Mark A. Lackey Pitch Notation Collection Editor: Mark A. Lackey Authors: Terry B. Ewell Catherine Schmidt-Jones Online: < http://cnx.org/content/col11353/1.3/ > CONNEXIONS Rice University, Houston, Texas This selection and arrangement of content as a collection is copyrighted by Mark A. Lackey. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). Collection structure revised: August 20, 2011 PDF generated: February 15, 2013 For copyright and attribution information for the modules contained in this collection, see p. 58. Table of Contents 1 The Sta ...........................................................................................1 2 The Notes on the Sta ...........................................................................5 3 Pitch: Sharp, Flat, and Natural Notes .........................................................11 4 Half Steps and Whole Steps ....................................................................15 5 Intervals ...........................................................................................21 6 Octaves and the Major-Minor Tonal System ..................................................37 7 Harmonic Series ..................................................................................45 Index ................................................................................................56 Attributions .........................................................................................58 iv Available -

MUSIC THEORY LEARNING GUIDE Level IB

MUSIC THEORY LEARNING GUIDE Level IB Edited by Elizabeth Riegert 2017 1 Music Theory Program – Level IB The Level IB program is intended for students in Intermediate Concert Band, Junior Orchestra and new members of Concert Choir. The program focuses on very simple skills of reading, notation and the language of music. Activities are noted in each section of this program guide and will be handed out in class. Extra copies can be found on Miss Riegert’s teacher blog (under VT Theory Units) at blogs.ubc.ca/elizabethriegert/. Assignments must be submitted on the due date; late assignments will not be accepted (unless due to excused absence or illness). All instruction will take place during class. Students with additional questions are encouraged to ask their classmates for help or to schedule a tutorial with Miss Riegert outside of regular class time. Assessment: 2 Written, Take-home Assignments 1 In-class Quiz 1 Final Test Topics 1. Pitch Naming a. Accidentals b. Clefs c. Enharmonic Names d. Whole Tones and Semitones e. Ledger lines 2. Scale Writing – Major/natural minor 3. Scale Degree Identification 4. Key Signature Identification a. Up to 5 sharps (#) and 3 flats (b) 5. Triads – Major/minor, inversions 6. Rhythm a. Dotted Rhythm b. Time Signatures c. Counting Systems 7. Musical Term Recognition – tempo, dynamics, style, technique, form 2 Grading Rubric Criteria Meeting Approaching Not Meeting Expectations Expectations Expectations Effort and Student is on time for Student attends class Student is not on Participation class with all with most of their time, or does not materials (theory materials and listens attend class (without package, homework, attentively to an excused absence) writing utensils, and discussion and does not bring instrument) and lecture. -

Computational Analysis of Audio Recordings and Music Scores for the Description and Discovery of Ottoman-Turkish Makam Music

Computational Analysis of Audio Recordings and Music Scores for the Description and Discovery of Ottoman-Turkish Makam Music Sertan Şentürk TESI DOCTORAL UPF / 2016 Director de la tesi Dr. Xavier Serra Casals Music Technology Group Department of Information and Communication Technologies Copyright © 2016 by Sertan Şentürk http://compmusic.upf.edu/senturk2016thesis http://www.sertansenturk.com/phd-thesis Dissertation submitted to the Department of Information and Com- munication Technologies of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR PER LA UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA, with the mention of European Doctor. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives 4.0 You are free to share – to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format under the following conditions: • Attribution – You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. • Non-commercial – You may not use the material for com- mercial purposes. • No Derivative Works – If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified ma- terial. Music Technology Group (http://mtg.upf.edu/), Department of Informa- tion and Communication Technologies (http://www.upf.edu/etic), Univer- sitat Pompeu Fabra (http://www.upf.edu), Barcelona, Spain The doctoral defense was held on .................. 2017 at Universitat Pompeu Fabra and scored as ........................................................... Dr. Xavier Serra Casals Thesis Supervisor Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), Barcelona, Spain Dr. Gerhard Widmer Thesis Committee Member Johannes Kepler University, Linz, Austria Dr.