Key and Mode in Seventeenth- Century Music Theory Books

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Dictionary of Music and Musicians

The New GROVE Dictionary of Music and Musicians EDITED BY Stanley Sadie 12 Meares - M utis London, 1980 376 Moda Harold Powers Mode (from Lat. modus: 'measure', 'standard'; 'manner', 'way'). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term 'mode' has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and in this century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain pheno mena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see SOUND, §5. I. The term. II. Medieval modal theory. III. Modal theo ries and polyphonic music. IV. Modal scales and folk song melodies. V. Mode as a musicological concept. I. The term I. Mensural notation. 2. Interval. 3. Scale or melody type. I. MENSURAL NOTATION. In this context the term 'mode' has two applications. First, it refers in general to the proportional durational relationship between brevis and /onga: the modus is perfectus (sometimes major) when the relationship is 3: l, imperfectus (sometimes minor) when it is 2 : I. (The attributives major and minor are more properly used with modus to distinguish the rela tion of /onga to maxima from the relation of brevis to longa, respectively.) In the earliest stages of mensural notation, the so called Franconian notation, 'modus' designated one of five to seven fixed arrangements of longs and breves in particular rhythms, called by scholars rhythmic modes. -

An App to Find Useful Glissandos on a Pedal Harp by Bill Ooms

HarpPedals An app to find useful glissandos on a pedal harp by Bill Ooms Introduction: For many years, harpists have relied on the excellent book “A Harpist’s Survival Guide to Glisses” by Kathy Bundock Moore. But if you are like me, you don’t always carry all of your books with you. Many of us now keep our music on an iPad®, so it would be convenient to have this information readily available on our tablet. For those of us who don’t use a tablet for our music, we may at least have an iPhone®1 with us. The goal of this app is to provide a quick and easy way to find the various pedal settings for commonly used glissandos in any key. Additionally, it would be nice to find pedal positions that produce a gliss for common chords (when possible). Device requirements: The application requires an iPhone or iPad running iOS 11.0 or higher. Devices with smaller screens will not provide enough space. The following devices are recommended: iPhone 7, 7Plus, 8, 8Plus, X iPad 9.7-inch, 10.5-inch, 12.9-inch Set the pedals with your finger: In the upper window, you can set the pedal positions by tapping the upper, middle, or lower position for flat, natural, and sharp pedal position. The scale or chord represented by the pedal position is shown in the list below the pedals (to the right side). Many pedal positions do not form a chord or scale, so this window may be blank. Often, there are several alternate combinations that can give the same notes. -

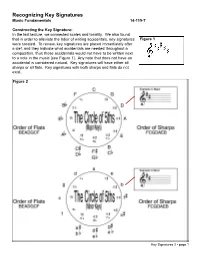

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T

Recognizing Key Signatures Music Fundamentals 14-119-T Constructing the Key Signature: In the last lecture, we connected scales and tonality. We also found that in order to alleviate the labor of writing accidentals, key signatures Figure 1 were created. To review, key signatures are placed immediately after a clef, and they indicate what accidentals are needed throughout a composition, thus those accidentals would not have to be written next to a note in the music [see Figure 1]. Any note that does not have an accidental is considered natural. Key signatures will have either all sharps or all flats. Key signatures with both sharps and flats do not exist. Figure 2 Key Signatures 2 - page 1 The Circle of 5ths: One of the easiest ways of recognizing key signatures is by using the circle of 5ths [see Figure 2]. To begin, we must simply memorize the key signature without any flats or sharps. For a major key, this is C-major and for a minor key, A-minor. After that, we can figure out the key signature by following the diagram in Figure 2. By adding one sharp, the key signature moves up a perfect 5th from what preceded it. Therefore, since C-major has not sharps or flats, by adding one sharp to the key signa- ture, we find G-major (G is a perfect 5th above C). You can see this by moving clockwise around the circle of 5ths. For key signatures with flats, we move counter-clockwise around the circle. Since we are moving “backwards,” it makes sense that by adding one flat, the key signature is a perfect 5th below from what preceded it. -

MTO 20.2: Wild, Vicentino's 31-Tone Compositional Theory

Volume 20, Number 2, June 2014 Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory Genus, Species and Mode in Vicentino’s 31-tone Compositional Theory Jonathan Wild NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.2/mto.14.20.2.wild.php KEYWORDS: Vicentino, enharmonicism, chromaticism, sixteenth century, tuning, genus, species, mode ABSTRACT: This article explores the pitch structures developed by Nicola Vicentino in his 1555 treatise L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica . I examine the rationale for his background gamut of 31 pitch classes, and document the relationships among his accounts of the genera, species, and modes, and between his and earlier accounts. Specially recorded and retuned audio examples illustrate some of the surviving enharmonic and chromatic musical passages. Received February 2014 Table of Contents Introduction [1] Tuning [4] The Archicembalo [8] Genus [10] Enharmonic division of the whole tone [13] Species [15] Mode [28] Composing in the genera [32] Conclusion [35] Introduction [1] In his treatise of 1555, L’Antica musica ridotta alla moderna prattica (henceforth L’Antica musica ), the theorist and composer Nicola Vicentino describes a tuning system comprising thirty-one tones to the octave, and presents several excerpts from compositions intended to be sung in that tuning. (1) The rich compositional theory he develops in the treatise, in concert with the few surviving musical passages, offers a tantalizing glimpse of an alternative pathway for musical development, one whose radically augmented pitch materials make possible a vast range of novel melodic gestures and harmonic successions. -

THE UBIQUITY of the DIATONIC SCALE Leon Crickmore

LEON CRICKMORE ICONEA 2012-2015, XXX-XXX The picture in figure 1 shows the old ‘School of Music’ here in Oxford. Right up to the nineteenth century, Boethius’s treatise De Institutione Musica was still a set book for anyone studying music in this University. The definition of a ‘musician’ contained in it reads as follows1: Is vero est musicus qui ratione perpensa canendi scientiam non servitio operis sed imperio speculationis adsumpsit THE UBIQUITY (But a musician is one who has gained knowledge of making music by weighing with reason, not through the servitude of work, OF THE DIATONIC SCALE but through the sovereignty of speculation2.) Such a hierarchical distinction between music Leon Crickmore theory and music practice was not finally overturned until the seventeenth century onward, by the sudden Abstract: increase in public musical performances on the There are an infinite number of possible one hand, and the development of experimental pitches within any octave. Why is it then, that in science on the other. But the origins of the so many different cultures and ages musicians distinction probably lie far in the past. Early in the have chosen to divide the octave into some kind of diatonic scale? This paper seeks to eleventh century, Guido D’Arezzo had expressed a demonstrate the ubiquity of the diatonic scale, similar sentiment, though rather more stridently, in and also to reflect on some possible reasons why a verse which, if that age had shared our modern this should be so. fashion for political correctness, would have been likely to have been censured: Musicorum et cantorum magna est distancia: Isti dicunt, illi sciunt quae componit musica. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

Universi^ Micfdmlms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality o f the material submitted. The following explanation o f techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image o f the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant As Corporate Knowledge

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2012 "Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge Jordan Timothy Ray Baker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Epistemology Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Jordan Timothy Ray, ""Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1360 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jordan Timothy Ray Baker entitled ""Sing to the Lord a new song": Memory, Music, Epistemology, and the Emergence of Gregorian Chant as Corporate Knowledge." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Rachel M. Golden, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: -

Phd Thesis, University of Helsinki, Department of Computer Science, November 2000

5 Quantisation hythm together with melody is one of the basic elements in music. According to Longuet-Higgins ([LH76]) human listeners are much more sensitive to the perception of rhythm than to the R perception of melody or pitch related features. Usually it is easier for trained and untrained listeners as well as for musicians to transcribe a rhythm, than details about heard intervals, harmonic changes or absolute pitch. “The term rhythm refers to the general sense of movement in time that characterizes our experience of music (Apel, 1972). Rhythm often refers to the organization of events in time, such that they combine perceptually into groups or induce a sense of meter (Cooper & Meyer, 1960; Lerdahl & Jackendoff, 1983). In this sense, rhythm is not an objective property of music, it is an experience that has both objective and subjective components. The experience of rhythm arises from the interaction of the various materials of music – pitch, intensity, timbre, and so forth – within the individual listener.” [LK94] In general the task of transcribing the rhythm of a performance is different from the previously described beat tracking or tempo detection issue. For estimating a tempo profile it is sufficient to infer score time positions for a set of dedicated anchor notes (i.e., beats respectively clicks), for the rhythm transcription task score time positions and durations for all performance notes must be inferred. Because the possible time positions in a score are specified as fractions using a rather small set of possible denominators, a score represents a grid of discrete time positions. The resolution of the grid is context and style dependent, common scores often uses only a resolution of 1/16th notes but higher resolutions (in most cases binary) or non-standard resolutions for arbitrary tuplets can always occur and might also be correct. -

Key Signatures Meters Tempo Clefs and Transpositions Position Work

The composition criteria for MSHSAA sight reading selections were revised in 2013-14. As a result, the committee determined that it would be beneficial to music directors throughout the state to have this criterion available to assist in preparations for sight reading. With this information in hand, directors will have a better understanding of the difficulty of the selection that will be used and will know what to expect in regard to rhythms, ranges, time signatures, etc. Key Signatures Key Signatures will be limited to the following: C, G, D, F, Bb major and relative natural minors. There should be at least one key signature change per piece. Meters Meters will be limited to the following: 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, Cut Time, 6/8 Tempo Tempi will be no slower than 72 beats per minute and no faster than 120 beats per minute. For continuous pieces, there will be at least one tempo change, but no more than two. Clefs and Transpositions Viola can have limited use of treble clef. Cello can have limited use of tenor clef. Position Work for Strings 3rd position and minimal use of 5th position may be used in the violin 1 part only. Minimal 3rd position work may be used in the violin 2 and viola parts. Half, 2nd, 3rd and 4th position work may be used in the cello part. Half position to the fourth position work may be used in the bass part. Divisi Limited use of divisi parts may be written. Repeats 1st and 2nd endings may be used. -

B.A.Western Music School of Music and Fine Arts

B.A.Western Music Curriculum and Syllabus (Based on Choice based Credit System) Effective from the Academic Year 2018-2019 School of Music and Fine Arts PROGRAM EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES (PEO) PEO1: Learn the fundamentals of the performance aspect of Western Classical Karnatic Music from the basics to an advanced level in a gradual manner. PEO2: Learn the theoretical concepts of Western Classical music simultaneously along with honing practical skill PEO3: Understand the historical evolution of Western Classical music through the various eras. PEO4: Develop an inquisitive mind to pursue further higher study and research in the field of Classical Art and publish research findings and innovations in seminars and journals. PEO5: Develop analytical, critical and innovative thinking skills, leadership qualities, and good attitude well prepared for lifelong learning and service to World Culture and Heritage. PROGRAM OUTCOME (PO) PO1: Understanding essentials of a performing art: Learning the rudiments of a Classical art and the various elements that go into the presentation of such an art. PO2: Developing theoretical knowledge: Learning the theory that goes behind the practice of a performing art supplements the learner to become a holistic practioner. PO3: Learning History and Culture: The contribution and patronage of various establishments, the background and evolution of Art. PO4: Allied Art forms: An overview of allied fields of art and exposure to World Music. PO5: Modern trends: Understanding the modern trends in Classical Arts and the contribution of revolutionaries of this century. PO6: Contribution to society: Applying knowledge learnt to teach students of future generations . PO7: Research and Further study: Encouraging further study and research into the field of Classical Art with focus on interdisciplinary study impacting society at large. -

Lecture Notes on Transposition and Reading an Orchestral Score

Lecture Notes on Transposition and Reading an Orchestral Score John Paul Ito Orchestral Scores The amount of information presented in an orchestral score can seem daunting, but a few simple things about the way the score is arranged can make it much more manageable. The instruments are grouped by families, in the following order: Woodwinds Horns Brass Percussion [Soloists, Singers] Strings Within each family, instruments are grouped by type, ordered with the higher instrument types higher within the family: Woodwinds: Flutes Oboes Clarinets Bassoons Brass: Trumpets Trombones Tubas Strings: Violin 1 Violin 2 Viola Cello Bass Notes on Transposition – © 2010 John Paul Ito 2 Similarly, individual instruments within an instrument type are ordered from high to low: Flutes Piccolo Flute Alto Flute Oboes Oboe Cor anglais Clarinets Eb Clarinet Clarinet Bass Clarinet Note that grouping by instrument type first means that the score will not reflect a consistent progression from high to low within instrument families. For example, among the woodwinds, the cor anglais will appear above the Eb clarinet, even though the Eb clarinet has a higher register. For the purposes of harmonic analysis, it is very convenient that scores are laid out with the strings on the bottom. This reflects an 18th-century concept of orchestration, in which the strings served as a foundation, with winds and brass added for extra color. Even into the 19th century, it remains true that all of the information needed for harmonic analysis is found in the strings, at the bottom of the score. This makes analysis easier, because string instruments are not transposing instruments.