BACH, Johann Sebastian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Werner-B02c[Erato-10CD].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2163/werner-b02c-erato-10cd-pdf-1912163.webp)

Werner-B02c[Erato-10CD].Pdf

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) The Cantatas, Volume 2 Heinrich Schütz Choir, Heilbronn Pforzheim Chamber Orchestra Württemberg Chamber Orchestra (B\,\1/ 102, 137, 150) Südwestfunk Orchestra, Baden-Baden (B\,\ry 51, 104) Fritz Werner L'Acad6mie Charles Cros, Grand Prix du disque (BWV 21, 26,130) For complete cantata texts please see www.bach-cantatas.com/IndexTexts.htm cD t 75.22 Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, BWV 2l My heart and soul were sore distrest . Mon cceur ötait plein d'ffiiction Domenica 3 post Trinitatis/Per ogni tempo Cantata for the Third Sunday after Trinity/For any time Pour le 3n"" Dimanche aprös la Trinitö/Pour tous les temps Am 3. Sonntag nachTrinitatis/Für jede Zeit Prima Parte 0l 1. Sinfonia 3.42 Oboe, violini, viola, basso continuo 02 2. Coro; Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis 4.06 Oboe, violini, viola, fagotto, basso continuo 03 3. Aria (Soprano): Seufzer, Tränen, Kummer, Not 4.50 Oboe, basso continuo ) 04 4. Recitativo (Tenore): Wie hast du dich, mein Gott 1.50 Violini, viola, basso continuo 05 5. Aria (Tenore): Bäche von gesalznen Zähren 5.58 Violini, viola, basso conlinuo 06 6. Coro: Was betrübst du dich, meine Seele 4.35 Oboe, violini, viola, fagotto, basso continuo Seconda Parte 07 7. Recitativo (Soprano, Basso): Ach Iesu, meine Ruh 1.38 Violini, viola, basso continuo 08 8. Duetto (Soprano, Basso): Komm, mein Jesu 4.34 Basso continuo 09 9. Coro: Sei nun wieder zufrieden 6.09 Oboe, tromboni, violini, viola, fagotto, basso continuo l0 10. Aria (Tenore): Erfreue dich, Seele 2.52 Basso continuo 11 11. -

11-15-2020-Worship-Online.Pdf

ORDER OF WORSHIP 24th Sunday after Pentecost November 15, 2020 GATHERING The people gather wherever they may in response to God’s call, offering praise in words of scripture, prayer, and song. The people acknowledge their sinfulness and receive the good news of God’s forgiveness. PRAYER BEFORE WORSHIP A time for quiet preparation before worship O Lord our God, we thank you for not hiding yourself from us. Instead, you promise to be found by us when we seek you with all of our hearts. In these times, we long for your presence from the time we wake up to the moment we lie down. Wherever we find ourselves, in whatever strife or predicament, we know your Spirit abides in us, through Jesus Christ, our Lord. Amen. PRELUDE Precatus est Moyses Charles Tournemire (L’Orgue Mystique 1870–1939) LIFE AND WORK OF THE CHURCH * CALL TO WORSHIP Come together to worship God who gives freely to all who call upon God's name. Let our voices rise to the courts of heaven with shouts of praise and hymns of glory. Be mindful of all of God's blessings and forget not his benefits. Let our spirits be free to acknowledge our salvation in the Risen Christ. Join with all of Creation as we seek first the Kingdom of God on earth. Let everything that has breath praise the Lord! * HYMN 4 Holy God, We Praise Your Name GROSSER GOTT PRAYER OF CONFESSION O King of mercy, we find ourselves once again in need of your grace and mercy. We have been lazy, quick to anger, and harsh with our neighbors. -

Instrumental - Copy

instrumental - Copy All Library Opus Score Parts Publishe Number Title # Composer Arranger Larger Work Instrumentation Y/N? Y/N? r Notes *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001 500 Hymns for Instruments* Lane, Harold Instruments Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-001 How Firm a Foundation Early American Melody Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the Joyful, Joyful, We Adore 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-002 Thee Beethoven, Ludwig van Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-003 To God Be the Glory Doane, W. H. Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the A Mighty Fortress Is Our 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-004 God Luther, Martin Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-005 How Great Thou Art! Swedish Folk Melody Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-006 O Worship the King Haydn, Johann Michael Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-007 Majestic Sweetness Hastings, Thomas Lane, Harold Instruments* Combinations N Y Lillenas "Worship in Song" *Accessory to the Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God 500 Hymns for Various Lillenas Hymnal, 0001-008 Almighty Dykes, John B. -

Hymnal Index V4

The Christian Life Hymnal – A Guide to the Indexes Each index in the hymnal has been developed and designed to aid worshippers in quickly finding specific titles and to learn more about the hymns they sing. This brief guide provides a description of each index to help the user better understand the index and how to gain the most from it. Scriptural Allusion Index (pp. 644-648)— This index provides scriptural references and allusions for each title. Some references may relate to a specific key word, thought, phrase, stanza or thought within the hymn; other references may allude to the overall content of the hymn or the topic under which it is found. Hymn Tune Index (pp. 648-651)— Each title in a hymnal is given an identifying tune name by its composer or hymnal editor. The tune name may be of personal or family significance, relate to the hymn’s history or usage, or something else entirely. This index lists tunes alphabetically for easy reference, along with the meter of the hymn. Metrical Tune Index (pp. 651-654)— Just as every title in the hymnal has a tune name, each title has a metrical desig- nation, or meter, as well. This numeric or alpha-numeric naming indicates and directly relates to the poetic meter or pulses, accents and cadences of the hymn lyrics. There are many different hymn meters in the hymnal. As a general rule, hymns having a meter identical to those of other hymns may be sung to those tunes. Hymns with “Irregular” meters have non-recurring pulses and accents in the lyrics and cannot be used with any other tune. -

Download Booklet

Johann Sebastian Bach 1685-1750 Cantatas Vol 10: Potsdam/Wittenberg SDG110 COVER SDG110 CD 1 70:45 For the Nineteenth Sunday after Trinity Ich elender Mensch, wer wird mich erlösen BWV 48 Wo soll ich fliehen hin BWV 5 Es reißet euch ein schrecklich Ende BWV 90 (For the Twenty-fifth Sunday after Trinity) Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen BWV 56 CD 2 51:01 For the Feast of the Reformation Gott der Herr ist Sonn und Schild BWV 79 Nun danket alle Gott BWV 192 C (Occasion unspecified) M Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott BWV 80 Y K Joanne Lunn soprano, William Towers alto James Gilchrist tenor, Peter Harvey bass The Monteverdi Choir The English Baroque Soloists John Eliot Gardiner Live recordings from the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage Erlöserkirche, Potsdam, 29 October 2000 Schlosskirche, Wittenberg, 31 October 2000 Soli Deo Gloria Volume 10 SDG 110 P 2005 Monteverdi Productions Ltd C 2005 Monteverdi Productions Ltd www.solideogloria.co.uk Edition by Reinhold Kubik, Breitkopf & Härtel Manufactured in Italy LC13772 8 43183 01102 5 10 SDG 110 Bach Cantatas Gardiner Bach Cantatas Gardiner CD 1 70:45 For the Nineteenth Sunday after Trinity The Monteverdi Choir The English Oboes 1-7 15:56 Ich elender Mensch, wer wird mich erlösen BWV 48 Baroque Soloists Xenia Löffler Sopranos James Eastaway 8-14 21:37 Wo soll ich fliehen hin BWV 5 Lucinda Houghton First Violins Mark Baigent 15-19 12:44 Es reißet euch ein schrecklich Ende BWV 90 Charlotte Mobbs Kati Debretzeni Joanne Lunn Nicolette Moonen Bassoon (For the Twenty-fifth Sunday after Trinity) Elin Manahan Thomas -

The World Rejoicing

The World Rejoicing The World Rejoicing was commissioned by the National Brass Band Associations of Belgium, Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, and the British Open, as the test piece for their competitions in 2020/21. Although the work was completed in 2019, the pandemic of 2020 meant that these competitions were postponed until 2021/22. The premiere will now take place in September 2021 at Symphony Hall, Birmingham, UK. In searching for a common link between the brass band traditions of the various European countries that commissioned this work, I considered the fact that hymns have always played an important role in the relationship that brass bands have with their particular communities; and thus I turned to a well- known Lutheran chorale, Nun danket alle Gott (Now thank we all our God), written around 1636 by Martin Rinkart, with the melody attributed to Johann Crüger. A number of composers have incorporated this chorale into their music, most famously J.S.Bach in his Cantatas no. 79 and 192, and Mendelssohn in the Lobsegang movement of his 2nd Symphony (the harmonization of which is usually used when this hymn is sung). It seemed fitting therefore for me to return to a compositional form I have used many times before (Variations) and to write a work based on this hymn. I have used it in a similar way to that which I employed in my Variations on Laudate Dominum of 1976 – that is, rather than writing a set of variations using elaborations of the complete tune, I have taken various phrases from the chorale and used them within the context of other musical material, applying an overall symphonic process of continuous variation and development. -

Now Thank We/Pno

1. Now thank we all our God 2. Oh, may our boun-teous God With hearts and hands and voic-es, Through all our life be near us, Who won-drous things hath done, With ev-er joy-ful hearts In whom his earth re-joice-es; And bless-ed peace to cheer us, Who, from our moth-ers’ arms, And keep us in his love, Hath blessed us on our way And guide us day and night, With count-less gifts of love, And free us from all ills, And still is ours to-day. Pro-tect us by his might. ««««««««««»»»»»»»»»» “Now Thank We All Our God,” is one of the most well known of Christian hymns. Due to its exultingly joyful music and text, it has been sung at many national commemorations such as the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. Catherine Winkworth provided the English translation in 1858. The German text, Nun danket alle Gott was written by Martin Rinkhart during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). Johann Crüger, born April 9, 1598, at Grossbreesen bei Guben in Prussia, was a major contributor of Lutheran hymns in the 17th Century. He studied with Paul Homberger in Regensburg, and in 1622 was appointed cantor at St. Nicholas Church in Berlin where he served until his death February 23, 1662. His chorale, Nun danket, first appears in 1647 with Jesu, meine Freude and Schmücke dich, O lieber Seele all of which were later harmonized in numerous settings by Johann Sebastian Bach. Felix Mendelssohn, born Feb. 3, 1809, in Hamburg, the son of a banker and grandson of a great Jewish scholar, was the the second of four children. -

SACRED MUSIC Volume 96, Number 2, Summer 1969

SACRED MUSIC Volume 96, Number 2, Summer 1969 Bartscht: Bachiana Brasileira, Steel and Brass SACRED MUSIC Volume 96, Number 2, Summer 1969 POPE PAUL ON SACRED MUSIC 3 WILLIAM ARTHUR REILLY ( 1903-1969) 8 Theodore Marier MUSICAL SUPPLEMENT 10 REVIEWS 20 NEWS 31 FROM THE EDITOR 33 LIST OF HONORARY MEMBERS AND VOTING MEMBERS 34 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of publication: 2115 Summit Avenue, Saint Paul, Minne sota 55101. Editorial office: University of Dallas, University of Dallas Station, Texas 7 5061. Editorial Board Rev. RalphS. March, S.O.Cist., Editor Mother C. A. Carroll, R.S.C.J. Rev. Lawrence Heiman, C.PP.S. J. Vincent Higginson Rev. Peter D. Nugent Rev. Elmer F. Pfeil Rev. Richard J. Schuler Frank D. Szynskie Editorial correspondence: Rev. RalphS. March, S.O.Cist., University of Dallas, University of Dallas Station, Texas 75061 News: Rev. Richard J. Schuler, College of St. Thomas, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55101 Music' for Review: Mother C. A. Carroll, R.S.C.J., Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart, Purchase, New York 10577 Rev. Elmer F. Pfeil 3257 South Lake Drive Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53207 Membership and Circulation: Frank D. Szynskie, Boys Town, Nebraska 68010 Advertising: Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O.Cist. CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Theodore Marier Vice-presz'dent . Noel Goemanne General Secretary Rev. Robert A. -

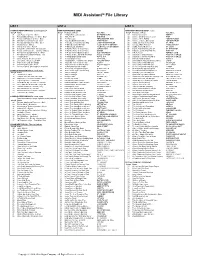

MIDI Assistant File Library

MIDI AssistantTM File Library LIST 1 LIST 2 LIST 3 COMMAND PERFORMANCES - D. Hollingsworth HYMN PERFORMANCE SERIES HYMN PERFORMANCE SERIES, cont'd Song # Name Song # First Line of Text Tune Name Song # First Line of Text Tune Name 01 Little Fugue in g minor - Bach 01 A Mighty Fortress Is Our God EIN FESTE BURG 01 Now the Day is Over MERRIAL 02 Passacaglia and Fugue in c minor - Bach 02 Abide With Me EVENTIDE 02 O Come and Sing Unto the Lord IRISH 03 Prelude and Fugue in g minor - Bach 03 Ah, Holy Jesus HERZLIEBSTER JESU 03 O Come, All Ye Faithful ADESTE FIDELES 04 Sinfonia from Cantata No. 29 - Bach 04 Alas! And Did My Savior Bleed MARTYRDOM 04 O Come, O Come, Emmanuel VENI EMMANUEL 05 Toccata and Fugue in d minor - Bach 05 All Creatures of Our God and King LASST UNS ERFREUEN 05 O God, Our Help In Ages Past ST. ANNE 06 Grand Choeur - Dubois 06 All Glory Be to God On High ALLEIN GOTT IN DER HOH 06 O Jesus, I Have Promised ANGEL'S STORY 07 Chorale in a minor - Franck 07 All Glory, Laud, and Honor VALET WILL ICH DIR GEBEN 07 O Little Town of Bethlehem ST. LOUIS 08 Sonata No. 1, First Mov't - Mendelssohn 08 All Hail the Power of Jesus' Name CORONATION 08 O Love That Wilt Not Let Me Go ST. MARGARET 09 Prelude on Rhosymedre - Vaughan-Williams 09 All Hail the Power of Jesus' Name DIADEM 09 O Master, Let Me Walk With Thee MARYTON 10 Toccata from Symphony No. -

STUDIES in LUTHERAN CHORALES by Hilton C

STUDIES IN LUTHERAN CHORALES by Hilton C. Oswald Edited by Bruce R. Backer ! Copyright 1981 by Dr. Martin Luther College, New Ulm, Minnesota All Rights Reserved Printed in U.S.A. • Redistributed in Digital Format By Permission TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITOR’S PREFACE! iii ABOUT THE AUTHOR! v 1!THREE REPRESENTATIVE CHORALES OF DR. MARTIN LUTHER! 1 1.1!A MIGHTY FORTRESS IS OUR GOD! 1 1.2!WE NOW IMPLORE GOD, THE HOLY GHOST! 3 1.3!IN THE MIDST OF EARTHLY LIFE! 4 2!CHORALES BY CONTEMPORARIES OF LUTHER! 7 2.1!MY SOUL, NOW BLESS THY MAKER! 7 2.2!IN THEE, LORD, HAVE I PUT MY TRUST! 8 3!THE UNFAMILIAR CHORALES OF DR. MARTIN LUTHER! 10 3.1!MAY GOD BESTOW ON US HIS GRACE! 10 3.2!WE ALL BELIEVE IN ONE TRUE GOD! 12 3.3!IN PEACE AND JOY I NOW DEPART! 14 3.4!O LORD, LOOK DOWN FROM HEAVEN, BEHOLD! 16 3.5!IF GOD HAD NOT BEEN ON OUR SIDE! 17 4!THE GREAT CHORALES OF LUTHER’S CONTEMPORARIES! 19 4.1!IN THEE, LORD, HAVE I PUT MY TRUST! 19 4.2!PRAISE GOD, THE LORD, YE SONS OF MEN! 20 4.3!ALL GLORY BE TO GOD ON HIGH! 22 4.4!LAMB OF GOD, PURE AND HOLY! 22 4.5!WHEN IN THE HOUR OF UTMOST NEED! 24 5!GREAT CHORALES OF THE 17TH CENTURY! 27 5.1!ZION MOURNS IN FEAR AND ANGUISH! 27 5.2!O DARKEST WOE! 28 5.3!ON CHRIST’S ASCENSION I NOW BUILD! 30 5.4!NOW THANK WE ALL OUR GOD! 31 5.5!O LORD, WE WELCOME THEE! 32 6!LUTHER’S ADAPTATIONS FROM THE HYMNODY OF THE OLD CHURCH! 33 6.1!JESUS CHRIST, OUR BLESSED SAVIOR! 33 6.2!O LORD, WE PRAISE THEE! 34 6.3!ALL PRAISE TO THEE, ETERNAL GOD! 35 6.4!CHRIST JESUS LAY IN DEATH’S STRONG BANDS! 37 6.5!COME, HOLY GHOST, GOD AND LORD! 39 i TABLE OF CONTENTS 7!THE CATECHISM CHORALES OF DR. -

Chapel Services

KING’SCOLLEGE CAMBRIDGE CHAPELSERVICES MICHAELMASTERM 2012 NOT TO BE TAKEN AWAY THE USE OF CAMERAS, RECORDING EQUIPMENT, VIDEO CAMERAS AND MOBILE PHONES IS NOT PERMITTED IN CHAPEL NOTICES SERMONS 30 September The Revd Dr Jeremy Morris Dean 7 October The Revd Richard Lloyd Morgan Chaplain 14 October The Revd Canon David Henley Team Rector, Broad Chalke 21 October The Revd David Chamberlin Rector, All Saints, Milton, Cambridge 28 October The Revd Dr Anders Bergquist Vicar, St John’s Wood 4 November The Very Revd Nicholas Frayling Dean of Chichester 11 November The Revd Bruce Kinsey Chaplain, The Perse School, Cambridge 18 November The Revd Terence Handley-McMath Chaplain, Harefield Hospital 25 November The Revd Richard Lloyd Morgan Chaplain 25 December The Revd Dr Jeremy Morris Dean SERVICE BOOKLETS Braille and large print service booklets are available from the Chapel Administrator for Evensong and Sung Eucharist services. CHORAL SERVICES Services are normally sung by King’s College Choir on Sundays and from Tuesdays to Saturdays. Services on Mondays are sung by King’s Voices, the College’s mixed voice choir. Exceptions are listed. ORGAN RECITALS Each Saturday during full term time there is an organ recital at 6.30 p.m. until 7.15 p.m. Admission is free, and there is a retiring collection. There will be no recital on 17 November. [ 2 ] MUSIC This term we welcome distinguished visitors from abroad. On Thursday 4 October at 7.30 p.m. the Choir is joined by Die Wiener Sängerknaben, and on Wednesday 14 November at 6.45 p.m. the counter-tenor Andreas Scholl sings a programme of Bach with the Academy of Ancient Music and the Choir. -

Chorale Book

AUGSBURG CHORALE BOOK AUGSBURG FORTRESS MINNEAPOLIS CONTENTS Foreword, iv All Glory Be to God on High, 81 Introduction, v Allein Gott in der Höh Setting by Chad Fothergill Composition & Performance Notes, vi We All Believe in One True God, 84 Wir glauben all Savior of the Nations, Come, 1 Setting by Helmut Barbe Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland Wake, Awake, for Night Is Flying, 88 Setting by Nancy M. Raabe Wachet auf O Savior, Rend the Heavens Wide, 4 Setting by Bartholomäus Gesius O Heiland, reiss die Himmel auf In Peace and Joy I Now Depart, 94 Setting by Johannes Brahms Mit Fried und Freud From Heaven Above, 12 Setting by Dietrich Buxtehude Vom Himmel hoch A Mighty Fortress Is Our God, 100 Setting by Daniel E. Schwandt Ein feste Burg Let All Together Praise Our God, 20 Setting by Georg Philipp Telemann Lobt Gott, ihr Christen Lord, Keep Us Steadfast in Your Word, 102 Setting by John Helgen Erhalt uns, Herr To Jordan Came the Christ, Our Lord, 22 Setting by Jeremy J. Bankson Christ, unser Herr Creator Spirit, Heavenly Dove, 106 Setting by Gerhard Krapf Veni Creator Spiritus / Komm, Gott Schöpfer O Morning Star, How Fair and Bright, 25 Setting by Anne Krentz Organ Wie schön leuchtet Salvation unto Us Has Come, 110 Setting by Hugo Distler Es ist das Heil The Only Son from Heaven, 30 Setting by Johann Walter Herr Christ, der einig Gotts Sohn Out of the Depths I Cry to You, 114 Setting by Robert Buckley Farlee Aus tiefer Not Ah, Holy Jesus, 40 Setting by Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy Herzliebster Jesu Now to the Holy Spirit Let Us Pray, 116 Setting by Ralph M.