Gordon Craig Thesis (PDF 2MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shimmen Full CV 2019

HEATHER SHIMMEN Born 1957, Melbourne 78. BA Fine Art (Painting), RMIT, Melbourne 2010 Artists in residence, RMIT, Melbourne , Vic 2013 Artist in residence, The Art Vault, Mildura, VIC SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019. ‘Ladies of the Pleiades’, Sale Regional Gallery, Sale 2017. 'Time Warps',Australian Galleries,Melbourne 2014. 'Insectivoria', Australian Galleries, Melbourne 2011. ‘The Swamp Maidens Tale’, Australian Galleries, Smith Street, Melbourne 2008. ‘Betwixt’, Gallery 101, Melbourne 2006 ‘I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls’, Stonnington Stables Museum of Art, Deakin University, Melbourne ‘Whispers’ Adele Boag Gallery, Adelaide 2005 ‘Figment, Fragment’, Gallery 101, Melbourne 2002 ‘Things That Float In The Air’, Joshua McClelland Print Room, Melbourne 1999. ‘The Sutured Heart’, Bulle Gallery, Melbourne 1997. ‘The Invisible Hand of the Future’, Lyall Burton Gallery, Melbourne 1996. Lyall Burton Gallery, Melbourne Adelaide Central Gallery, Adelaide 1993 Adelaide Central Gallery, Adelaide Lyall Burton Gallery, Melbourne 1991. Realities Gallery, Melbourne 1990. Realities Gallery, Melbourne 1986. Realities Gallery, Melbourne 1984 Bitumen River Gallery, Canberra 1983. Anthill Theatre, Melbourne 1982. Drummond Street Gallery, Melbourne GROUP EXHIBITION 2020. ‘Let All the Birds Fly- the hybrid print’,Maitland Regional Galleries,NSW ‘Fem -aFfinity’, Devonport Regional Art Gallery Tas Benalla Art GalleryVic Noosa Regional Art Gallery Qld Horsham Regional Art Gallery Vic Bunjil Place Gallery Vic Riddoch Art GallerySA 2019 ‘Paper Made’, Australian Galleries, Melbourne ‘Fem-aFfinity’, Arts Project, Melbourne ‘Beyond the Veil’,Art for the World Gallery, Cannaregio, Biennale de Venetzia, Venice,Italy ‘Beyond the Veil’,Memoire de L’Avenir Espace cultures pluridisciplinairl, Paris, France ‘2019 Ulsan International Woodcut Biennale’ South Korea ‘Round About’ Gecko Gallery, Fish Creek,VIC ‘Sydney Contemporary Art Fair’Sydney,NSW ‘Art Meets Nature’,WAMA, Sofitel,Melbourne ‘A Fine Line’, Bright Space, Melbourne 2018. -

Library Board of Victoria Annual Report 2016

Library Board of Victoria Victoria Library of Board Library Board of Victoria Annual Report 2016–17 Annual ReportAnnual 2016–17 Library Board of Victoria Annual Report 2016–17 Published by State Library Victoria 328 Swanston Street Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia Also published on slv.vic.gov.au © State Library Victoria 2017 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government 328 Swanston Street Melbourne VIC 3000 Australia Typeset by Cannon Typesetting Cover photograph: The night garden, illumination created by Nick Azidis, Lisa Greenaway and Rose Staff for White Night Melbourne 2017. Photograph by James Braund. Contents 2 President’s report 4 Chief Executive Officer’s year in review 6 Vision and values 7 Report of operations 22 Financial summary 24 2016–17 key performance indicators 25 Service Agreement with the Minister for Creative Industries 26 Output framework 28 Acquisitions statistics 29 Library Board and corporate governance 33 Library Executive 34 Organisational structure 35 Occupational health and safety 37 Public sector values and employment principles 38 Statement of workforce data and merit and equity 40 Environmental performance 42 Diversity and Social Inclusion Plan 43 Freedom of information 44 Protected Disclosure Act 2012 44 Compliance with the Building Act 1993 45 Victorian Industry Participation Policy 45 National Competition Policy 46 Government advertising expenditure 46 Major contracts 47 Consultancies 48 Financial information 49 Risk attestation Financial statements 51 Auditor-General’s report 53 Library Board of Victoria letter 54 Financial report for year ended 30 June 2017 59 Notes to the financial statements 105 Disclosure index President’s report I am pleased to present my sixth report as the donated $2 million to establish Start Space, a new President of the Library Board of Victoria. -

James Turrell's Skyspace Robert Dowling Life, Death

HANS HEYSEN ROBERT DOWLING ROBERT LIFE, DEATH AND MAGIC AND MAGIC LIFE, DEATH JAMES TURRELL’S SKYSPACE SKYSPACE TURRELL’S JAMES ISSUE 62 • winter 2010 artonview ISSUE 62 • WINTER 2010 NATIONAL GALLERY OF AUSTRALIA The National Gallery of Australia is an Australian Government Agency Issue 62, winter 2010 published quarterly by 3 Director’s foreword National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 exhibitions and displays Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au 6 Robert Dowling: Tasmanian son of Empire ISSN 1323-4552 Anne Gray Print Post Approved 10 Life, death and magic: 2000 years of Southeast Asian pp255003/00078 ancestral art © National Gallery of Australia 2010 Copyright for reproductions of artworks is Robyn Maxwell held by the artists or their estates. Apart from 16 Hans Heysen uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of artonview may be reproduced, Anne Gray transmitted or copied without the prior permission of the National Gallery of Australia. 20 Portraits from India 1850s–1950s Enquiries about permissions should be made in Anne O’Hehir writing to the Rights and Permissions Officer. 22 In the Japanese manner: Australian prints 1900–1940 The opinions expressed in artonview are not necessarily those of the editor or publisher. Emma Colton Produced the National Gallery of Australia Publishing Department: acquisitions editor Eric Meredith 26 James Turrell Skyspace designer Kristin Thomas Lucina Ward photography Eleni Kypridis, Barry Le Lievre, Brenton McGeachie, Steve Nebauer, 28 Theo van Doesburg Space-time construction #3 David Pang, -

Foundation Annual Report 2012–13

FOUNDATION ANNUAL REPORT 2012–13 FOUNDATION ANNUAL REPORT 2012–13 Polixeni Papapetrou born Australia 1960 Mark Elvis impersonator at Elvis Grotto Melbourne 1992 gelatin silver photograph image 100 x 100 cm gift of Patrick Corrigan, 2013 through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program © Polixeni Papapetrou Contents Office bearers 5 Objectives 5 Chairman’s report 7 Contributors 22 Membership 39 Financial statements 61 Colin McCahon New Zealand 1919–1987 Muriwai. Necessary protection 1972 synthetic polymer paint on composition board 60.8 x 81.2 cm bequest of Jane Flecknoe, 2013 100 Works for 100 Years © Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust 4 natIonal gallerY of AUStralIA Office bearers Objectives Patron The National Gallery of Australia Her Excellency Ms Quentin Bryce AC Foundation, a company limited by The Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia guarantee under the Corporations Law, is a non-profit organisation established to Board members support the National Gallery of Australia. Mr John Hindmarsh AM (appointed 20.9.04; The principal objectives of the Foundation Chairman 27.10.10) are to: Ms Susan Armitage (appointed 11.5.11) Mr Philip Bacon AM (appointed 26.10.00) ■■ maintain, improve and develop Mr Julian Beaumont (appointed 28.10.09) the national collection of works of Ms Sandra Benjamin OAM (appointed 27.4.06) art owned by the National Gallery Mr Anthony R Berg AM (appointed 16.3.99; of Australia Chairman 16.3.99 to 26.4.06) ■■ promote, maintain, improve and Mrs Robyn Burke (appointed 29.8.06) develop the National Gallery of Australia Mr Terrence A Campbell AO (appointed 28.2.07) ■■ support the development and conduct Mr David Coe (appointed 13.10.00, resigned 21.1.13) by the National Gallery of Australia of The Hon Mrs Ashley Dawson-Damer (appointed 5.5.04) travelling exhibitions of works of art Dr Lee MacCormick-Edwards (appointed 26.10.11) ■■ raise money to achieve these Mr James Erskine (appointed 11.5.11) objectives. -

Heide Museum of Modern Art 2003 Annual Report

HEIDE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 2003 ANNUAL REPORT Heide Museum of Modern Art HEIDE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 2003 ANNUAL REPORTHEIDE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 2003 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS PAGE CONTENTS 1 Mission 3 2 Patrons, Fellows, 4 Board of Directors and Company Members 3 Chairman’s Report 5 4 Operations Report 6 5 Exhibitions and Events 11 6 Acquisitions 13 7 Outward Loans 15 8 Lenders 16 9 Donors and Partners 17 10 Staff and Volunteers 21 11 Financial Statements 23 HEIDE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 2003 ANNUAL REPORT MISSION STATEMENT Heide Museum of Modern Art tells the story of modern art in Australia through the heritage of John and Sunday Reed and the unique environment in which they lived. The Museum maintains their philosophy of support for contemporary art. 3 HEIDE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 2003 ANNUAL REPORT PATRONS, FELLOWS, FOUNDING PATRON BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD OF DIRECTORS Sir Rupert Hamer AC KCMG, 1916 – 2004 Trevor Tappenden Chairman AND COMPANY MEMBERS Kerry Gardner Deputy Chairman PATRON Mrs Terry Bracks Dr Janine Burke Craig Kimberley (from December) FELLOWS Bryce Menzies Dr H Norman B Wettenhall AM, 1988 1915 – 2000 Ken Ryan (from December) Georges Mora, 1913 – 1992 1989 David Walsh Maria Prendergast 1990 Baillieu Myer AC 1992 Rob Adams (to March) Loti Smorgon AO 1993 James Colquhoun (to October) Victor Smorgon AO 1993 Michael Roux (to March) Dr Barrett Reid AM, 1926 – 1995 1994 Dr Tom Quirk 1995 COMPANY MEMBERS Maudie Palmer 1997 Helen Alter The Hon. Mr Justice Charles 1998 Ken Cato Christine Collingwood 1999 The Hon. Mr Justice Charles Albert Tucker AO, 1914 – 1999 2000 Joan Clemenger Barbara Tucker 2000 Christine Collingwood Tom Lowenstein 2002 Patricia Cross Janne Faulkner AM Jeff Floyd Julia King Tom Lowenstein Professor Ray Martin Sarah McKay Ian McRae Dr Thomas Quirk Rosemary Simpson Deryk Stephens Chris Thomas 4 HEIDE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 2003 ANNUAL REPORT CHAIRMAN’S REPORT During 2003 Heide underwent significant increased to ensure we can continue to transition to re-emerge as a major art operate to the high standards we seek and destination. -

Annual Report 2014–15

Annual Report 2014–15 Annual Report 2014–15 Published by the National Gallery of Australia Parkes Place, Canberra ACT 2600 GPO Box 1150, Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au/aboutus/reports ISSN 1323 5192 © National Gallery of Australia 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Prepared by the Governance and Reporting Department Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Carla Da Silva Pastrello Figures by Michael Tonna Index by Sherrey Quinn Printed by Union Offset Printers Cover: The 2015 Summer Art Scholars with Senior Curator Franchesca Cubillo in the Indigenous Urban gallery, 14 January 2015. 16 October 2015 Senator the Hon Mitch Fifield Minister for Communications Minister for the Arts Minister Assisting the Prime Minister for Digital Government Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister On behalf of the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, I have pleasure in submitting to you, for presentation to each House of Parliament, the National Gallery of Australia’s annual report covering the period 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015. This report is submitted to you as required by section 39 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. It is consistent with the requirements set out in the Commonwealth Authorities (Annual Reporting) Orders 2011, and due consideration has been given to the Requirements for Annual Reports approved by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit under subsections 63(2) and 70(2) of the Public Service Act 1999 and made available by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet on 25 June 2015. -

John Cruthers

MENZIES AUSTRALIAN & INTERNATIONAL FINE ART & SCULPTURE Sydney 24 September 2015 Several of the best works in this sale are well above the buying budgets of my clients, so as usual I have not written about them. This is a shame, because if any of you has a spare $350,000, Ian Fairweather’s Fascismo is a superb late painting and easily museum standard. But overall it’s an interesting sale containing some unusual and offbeat items. So I have taken the opportunity to introduce some new artists I’ve not previously recommended, and to reiterate my enthusiasm for a couple of others I’ve had little success with. Other works I’ve not recommended because I have no-one collecting in the area, for example the two terrific 1973 prints by US pop master Jim Dine, or the 1976 screenprint by Bridget Riley, the major figure in the international op art movement. I hope you enjoy seeing some new artists and, as always, I am very pleased to discuss any works of interest to you that I have not included in the presentation. JOHN CRUTHERS rococo pop pty ltd In a recent sale I recommended a painting by Albert Tucker called Woman 1950, of a prostitute standing in a doorway in a bombed-out looking Paris. I commented that the years Tucker spent overseas, roughly 1947-60, represented a highpoint in his work. He saw a lot of great art, worked hard and strove to produce work that measured up to the best contemporary art he was seeing. The current work is a study in which Tucker tries a variety of stylistic devices borrowed from late cubism to depict the female form in interior space. -

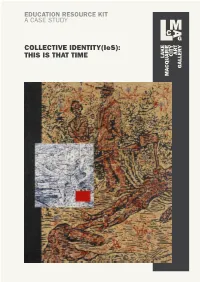

Collective Identity(Ies): This Is That Time

EDUCATION RESOURCE KIT A CASE STUDY COLLECTIVE IDENTITY(IeS): THIS IS THAT TIME 1 INTRODUCTION With the education strategies written by Kate Caddey, the exhibition text prepared by Lisa Corsi and published by Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery, this education kit is designed to assist senior secondary Visual Arts teachers and students in the preparation, appreciation and understanding of the case study component of the HSC syllabus. The gallery is proud to support educators and students in the community with an ongoing series of case studies as they relate to the gallery’s exhibition program. This education resource kit is available directly from the gallery, or online at www.artgallery.lakemac.com.au. A CASE STUDY A series of case studies (a minimum of FIVE) should be undertaken with students in the HSC course. The selection of content for the case study should relate various aspects of critical and historical investigations, taking into account practice, the conceptual framework Cover: and the frames. Emphasis may be given to a particular Gordon Bennett aspect of content although all should remain in play. The Nine Ricochets (Fall down black fella, jump up white fella) 1990 Case studies should be 4–10 hours in duration in the oil and synthetic polymer paint HSC course. on canvas and canvas boards 220 x 182cm image courtesy the artist and NSW Board of Studies, Visual Arts Stage 6 Syllabus, 2012 Milani Gallery, Brisbane. photo Carl Warner private collection, Brisbane CONTENTS ABOUT THIS EDUCATION RESOURCE KIT COLLECTIVE IDENTITY(IeS) ESSAY -

Prints, Printmaking and Philanthropy a Symposium Celebrating 50 Years of the Harold Wright and the Sarah and William Holmes Scholarships

Prints, Printmaking and Philanthropy A symposium celebrating 50 years of The Harold Wright and The Sarah and William Holmes Scholarships 30 September – 2 October, 2019 Forum Theatre, Arts West, The University of Melbourne Prints, Printmaking SYMPOSIUM and Philanthropy PROGram A symposium celebrating 50 years of The Harold Wright and The Sarah and DAY ONE Monday 30 September William Holmes Scholarships 8.30 – 9.00 am Registration Presented by the Australian Institute of Art History 9.00 – 9.15 am Introduction and Welcome Professor Su Baker, Pro Vice-Chancellor, Community and Cultural Partnerships, with assistance from The University of Melbourne’s and Director of Centre of Visual Arts (CoVA), The University of Melbourne Students and Scholarly Services Associate Professor Christopher Marshall, Chair, The Harold Wright and 30 September – 2 October, 2019 The Sarah & William Holmes Scholarships Selection Committee, The University of Melbourne 9.15 – 10.15 am Session One – Prints & Experimentation Chair: Julie Irving, Lecturer, Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, The University of Melbourne Dr Jane Eckett, Art History Program, School of Culture and Communication, The University of Melbourne Can a visionary act of philanthropy transform print scholarship and curatorial practice? This symposium will Hirschfeld-Mack’s monotypes as an index of modernist migration explore this question. Celebrating 50 years of The Harold Wright and The Sarah and William Holmes Scholarships, Dr Anna Parlane, Art History Program, School of Culture and Communication, Prints, Printmaking and Philanthropy will focus on three broad themes: print exhibitions, print collections and The University of Melbourne “Collapse of Mirror City”: Fact, fabrication and the newspaper print in Michael print presses – and also seek to trace the influence of philanthropy in shaping Australasian print culture. -

MS 49 Papers of the Print Council of Australia Australian Prints and Printmaking Collection

MS 49 Papers of the Print Council of Australia Australian Prints and Printmaking Collection Summary Administrative Information Biographical Note Associated Content Acronyms Used Box Description Folder Description Summary Creator: Print Council of Australia Title: Papers of the Print Council of Australia Date range: 1966 - 2000 Reference number: MS 49 Extent: 95 boxes + 11 ring binders Prepared By: Peta Jane Jones Overview The collection represents a non-governmental organisation involved in the visual arts with broad activities and influence. The collection includes mainly correspondence, exhibition details, printmakers, gallery/art centres, colleges/universities, entry forms, slides, receipts and copies of newspaper clippings. They provide a comprehensive history of the administrative processes of the council and its exhibitions. The majority of the collection contains correspondence written by administrative staff; of greater interest is the correspondence, often handwritten by the artists themselves. In the earlier boxes the exhibition detail is more comprehensive with itineraries (drafts and finals) and forms stating the exhibiting galleries and artist lists with print sales included. Also of interest are the artists’ biographies, sometimes with handwritten notes; these were used for exhibition catalogues, print directories, Imprint and member print submissions. There are approximately 2000 slides in this collection mainly representing prints associated with PCA exhibitions. PCA committee records including ballot forms for nominating committee members, agendas and minutes of Annual General meetings, bank statements and bank reconciliation statements also comprises part of the collection. Keywords 1 Australian Printmaking; Exhibitions (see biographical section for list); patron/member prints. Key Names Grahame King; Robert Grieve; Geoff La Gerche; Neil Caffin; Udo Sellbach; Roger Butler; Barbara Hanrahan; various printmakers (see biographical section). -

Annual Report 2008–09 Annu Al Repor T 20 08–0 9

ANNUAL REPORT 2008–09 ANNUAL REPORT 2008–09 REPORT ANNUAL ANNUAL REPORT 2008–09 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the cultural enrichment of all Australians through access to their national art gallery, the quality of the national collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and programs, and the professionalism of Gallery staff. The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, corporate governance, administration and financial and business management. In 2008–09, the National Gallery of Australia received an appropriation from the Australian Government totalling $78.494 million (including an equity injection of $4 million for development of the national collection and $32.698 million for Stage 1 of the building extension project), raised $19.32 million, and employed 256.4 full- time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2009 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Produced by the Publishing Department of the National Gallery of Australia Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Carla Da Silva Printed by Blue Star Print, Canberra National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au/reports -

Mike Parr Blind Self Portraits

ARNDT BERLIN POTSDAMER STRASSE 96 10785 BERLIN GERMANY PHONE +49 30 206 138 70 [email protected] WWW.ARNDTBERLIN.COM MIKE PARR BLIND SELF PORTRAITS 21 SEPTEMBER – 02 NOVEMBER 2013 FOREWORD I knew of Mike Parr’s performance work long before I was aware it was the work of an Australian artist. When I moved to Australia with my family two years ago, my goal was to focus on bringing major international and Asian art to Australia and the best work from Southeast Asia to Europe. I decided to leave Australian art to the experts, who could serve the work far better. On a number of occasions over the past twenty-five years of my career, reality has shown that exceptions need to be made, and this was now the case with Australian art. For whenever and wherever I went in Australia – museums, foundations and private collections – I saw the most stunning, breathtaking works by Mike Parr. For the past twenty years my mission in Berlin has been to bring major artists and their work to audiences who would otherwise not encounter these radical positions, and this mission continues for the Asia-Pacific art landscapes. When Mike Parr and I finally met about his work, we discovered our missions and visions overlapped. I felt strongly that his work needed to be seen and engaged within a European context. Meanwhile, he was prepared to dedicate two years of creation towards an exhibition of new work in Berlin. The result: Berlin and Western audiences connect immediately and instinctively with Mike Parr’s work, without questioning whether they are viewing the work of an Australian artist.