The Spaciotemporal Patterns of Georgian Winter Solstice Festivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

Evaluating the Invasive Potential of an Exotic Scale Insect Associated with Annual Christmas Tree Harvest and Distribution in the Southeastern U.S

Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100013 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Trees, Forests and People journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tfp Evaluating the invasive potential of an exotic scale insect associated with annual Christmas tree harvest and distribution in the southeastern U.S. Adam G. Dale a,∗, Travis Birdsell b, Jill Sidebottom c a University of Florida, Entomology and Nematology Department, Gainesville, FL 32611 b North Carolina State University, NC Cooperative Extension, Ashe County, NC c North Carolina State University, College of Natural Resources, Mountain Horticultural Crops Research and Extension Center, Mills River, NC 28759 a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Keywords: The movement of invasive species is a global threat to ecosystems and economies. Scale insects (Hemiptera: Forest entomology Coccoidea) are particularly well-suited to avoid detection, invade new habitats, and escape control efforts. In Fiorinia externa countries that celebrate Christmas, the annual movement of Christmas trees has in at least one instance been Elongate hemlock scale associated with the invasion of a scale insect pest and subsequent devastation of indigenous forest species. In the Conifers eastern United States, except for Florida, Fiorinia externa is a well-established exotic scale insect pest of keystone Fraser fir hemlock species and Fraser fir Christmas trees. Annually, several hundred thousand Fraser firs are harvested and shipped into Florida, USA for sale to homeowners and businesses. There is concern that this insect may disperse from Christmas trees and establish on Florida conifers of economic and conservation interest. Here, we investigate the invasive potential of F. -

Water in Mythology

Water in Mythology Michael Witzel Abstract: Water in its various forms–as salty ocean water, as sweet river water, or as rain–has played a major role in human myths, from the hypothetical, reconstructed stories of our ancestral “African Eve” to those recorded some ½ve thousand years ago by the early civilizations to the myriad myths told by major and smaller religions today. With the advent of agriculture, the importance of access to water was incorporated into the preexisting myths of hunter-gatherers. This is evident in myths of the ancient riverine civilizations of Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, and China, as well as those of desert civilizations of the Pueblo or Arab populations. Our body, like the surface of the earth, is more than 60 percent water. Ancient myths have always rec- ognized the importance of water to our origins and livelihood, frequently claiming that the world began from a watery expanse. Water in its various forms–as salty ocean water, as sweet river water, or as rain–has played a major role in human tales since our earliest myths were re - corded in Egypt and Mesopotamia some ½ve thou- sand years ago. Thus, in this essay we will look to - ward both ancient and recent myths that deal with these forms of water, and we will also consider what influence the ready availability (or not) of water had on the formation of our great and minor early civi- lizations. Many of our oldest collections of myths introduce the world as nothing but a vast salty ocean. The old - MICHAEL WITZEL, a Fellow of the est Indian text, the poetic Ṛgveda (circa 1200 BCE), American Academy since 2003, is asserts: “In the beginning, darkness was hidden by the Wales Professor of Sanskrit at darkness; all this [world] was an unrecognizable Harvard University. -

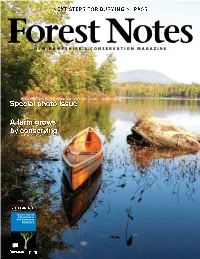

Special Photo Issue a Farm Grows by Conserving

NEXT STEPS FOR BURYING N. PASS Forest Notes NEW HAMPSHIRE’S CONSERVATION MAGAZINE Special photo issue A farm grows by conserving AUTUMN 2015 forestsociety.org Locate Your Organization Here Convenient access to the water & Portsmouth Harbor The Historic Creek Farm e ForestFFororest SSocietyociettyy is lookinglooking forfor a partnerpartner with similar sstewardshiptewarddshipship interinterestseestssts to lease the buildings and 35-a35-acrecre ccoastaloastal prpropertyoperty at CrCreekeek FFarmarm in PPortsmouth.ortsmouth. AvailableAvailable in 2017 – SuitableSuittabable forfor nonprotnnonprot organizationsorgganizanizations or institinstitutionsutionsu – HHistHistoric,isttororic, 19,460 sqsq.. ft. cottcottagetagaggee with 2-st2-storytorororyy utilitutilitytyy buildingbuildiing and garageggararragage – 1,125 ffeeteet off frfrontageonttagaggee on SSagamoreaggamoramorree CrCreekreekeeeek – DoDockck and aaccessccesscess ttoo PPorPortsmouthortsmouth HHarbHarborarbor Historic, 19,460 sq. ft. cottage with 2-story utility building and garage Contact Jane James 115050 MirMironaona Rd PPortsmouth,ortsmouth, NH 03801 CelCell:ll:l: (603) 817-0649 [email protected]@marpleleejames.comjames.com TABLE OF CONTENTS: AUTUMN 2015, N o. 284 4 23 30 DEPARTMENTS 2 THE FORESTER’S PRISM 3 THE WOODPILE 14 IN THE FIELD Fall is tree-tagging season at The Rocks Estate. FEATURE 16 CONSERVATION SUCCESS STORIES 4 Winning Shots How a conservation easement is protecting working forests while A photo essay featuring the winners of the First Annual providing capital that will help the last dairy farm in Temple, N.H. Forest Notes Photo Contest. keep growing. A landowner in Wilton with roots going back to the town’s first settlers donates a conservation easement on his hilltop farm. 23 WOODS WISE Most of our reservations aren’t well-known recreation destinations, and that can be a good thing. -

University of Groningen Greek Religion, Hades, Hera And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Greek Religion, Hades, Hera and Scapegoat, and Transmigration Bremmer, J.N. Published in: EPRINTS-BOOK-TITLE IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Bremmer, J. N. (2005). Greek Religion, Hades, Hera and Scapegoat, and Transmigration. In EPRINTS- BOOK-TITLE Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 GREEK RELIGION has long been the most important religion for Western European scholars who attempted to gain a better understanding of the phenomenon of religion. Great historians of religion, from Vico and Herder to Friedrich Max Müller, Jane Ellen Harrison and Frazer of The Golden Bough , all steeped themselves in the religious legacy of the Greeks whom they considered superior to all other nations of the past. -

Slavic Pagan World

Slavic Pagan World 1 Slavic Pagan World Compilation by Garry Green Welcome to Slavic Pagan World: Slavic Pagan Beliefs, Gods, Myths, Recipes, Magic, Spells, Divinations, Remedies, Songs. 2 Table of Content Slavic Pagan Beliefs 5 Slavic neighbors. 5 Dualism & The Origins of Slavic Belief 6 The Elements 6 Totems 7 Creation Myths 8 The World Tree. 10 Origin of Witchcraft - a story 11 Slavic pagan calendar and festivals 11 A small dictionary of slavic pagan gods & goddesses 15 Slavic Ritual Recipes 20 An Ancient Slavic Herbal 23 Slavic Magick & Folk Medicine 29 Divinations 34 Remedies 39 Slavic Pagan Holidays 45 Slavic Gods & Goddesses 58 Slavic Pagan Songs 82 Organised pagan cult in Kievan Rus' 89 Introduction 89 Selected deities and concepts in slavic religion 92 Personification and anthropomorphisation 108 "Core" concepts and gods in slavonic cosmology 110 3 Evolution of the eastern slavic beliefs 111 Foreign influence on slavic religion 112 Conclusion 119 Pagan ages in Poland 120 Polish Supernatural Spirits 120 Polish Folk Magic 125 Polish Pagan Pantheon 131 4 Slavic Pagan Beliefs The Slavic peoples are not a "race". Like the Romance and Germanic peoples, they are related by area and culture, not so much by blood. Today there are thirteen different Slavic groups divided into three blocs, Eastern, Southern and Western. These include the Russians, Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Serbians,Croatians, Macedonians, Slovenians, Bulgarians, Kashubians, Albanians and Slovakians. Although the Lithuanians, Estonians and Latvians are of Baltic tribes, we are including some of their customs as they are similar to those of their Slavic neighbors. Slavic Runes were called "Runitsa", "Cherty y Rezy" ("Strokes and Cuts") and later, "Vlesovitsa". -

And Darkness-World. an Andean Healing Ritual for Being Struck by Lightning

Field-Work Reports Lightning from the Upper-, Earth- and Darkness-World. An Andean Healing Ritual for Being Struck by Lightning. CONTENTS SUMMARY, ZUSAMMENFASSUNG, RESUMEN 1. Lightning in Andean ethnology: Locating the present study 2. The healing ritual 2.1 First phase: Mesa for the gloria lightning 2.2 Second phase: Mesa for the lightning of the mountain spirits 2.3 Third phase: Mesa for the lightning that struck the earth 2.4 Fourth phase: Mesa for the lightning of the Darkness-World 2.5 Fifth phase: Incense ceremony and burning of the mesa for the gloria lightning 2.6 Sixth phase: Purification, burning, and calling the lost soul 3. Final words: Innumerable lightnings in comparative data NOTES CITED LITERATURE I am deeply indebted to the following institutions which support my ethnomedical research in Bolivia: Robert Bosch Stiftung, Stiftung Volkswagenwerk, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, and the Universitat Ulm. I also would like to express my deep gratitude to all Callawaya medicinemen and patients who gave me the opportunity to learn from their wisdom and life. SUMMARY: The present empirical study is based on participant observation and complete tape recorded documentation of seven healing rituals for being struck by lightning as performed by the Callawaya medicinemen in the Andes of Bolivia. One of them is described in detail including a selection of pray- ers that accompanies it in its original version (Quechua). A comparison between this ritual and the others documented by the author as well as what Andean studies have up to now contributed to the understanding of lightning as a numen and as an occasion for rituals does highlight the unique concep- tual and ritual richness of the one described thus contributing to an expansion and deepening of our understanding of Andean religion and Andean ritual culture. -

Biological Sciences

A Comprehensive Book on Environmentalism Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction to Environmentalism Chapter 2 - Environmental Movement Chapter 3 - Conservation Movement Chapter 4 - Green Politics Chapter 5 - Environmental Movement in the United States Chapter 6 - Environmental Movement in New Zealand & Australia Chapter 7 - Free-Market Environmentalism Chapter 8 - Evangelical Environmentalism Chapter 9 -WT Timeline of History of Environmentalism _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ A Comprehensive Book on Enzymes Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction to Enzyme Chapter 2 - Cofactors Chapter 3 - Enzyme Kinetics Chapter 4 - Enzyme Inhibitor Chapter 5 - Enzymes Assay and Substrate WT _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ A Comprehensive Introduction to Bioenergy Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Bioenergy Chapter 2 - Biomass Chapter 3 - Bioconversion of Biomass to Mixed Alcohol Fuels Chapter 4 - Thermal Depolymerization Chapter 5 - Wood Fuel Chapter 6 - Biomass Heating System Chapter 7 - Vegetable Oil Fuel Chapter 8 - Methanol Fuel Chapter 9 - Cellulosic Ethanol Chapter 10 - Butanol Fuel Chapter 11 - Algae Fuel Chapter 12 - Waste-to-energy and Renewable Fuels Chapter 13 WT- Food vs. Fuel _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ A Comprehensive Introduction to Botany Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Botany Chapter 2 - History of Botany Chapter 3 - Paleobotany Chapter 4 - Flora Chapter 5 - Adventitiousness and Ampelography Chapter 6 - Chimera (Plant) and Evergreen Chapter -

Biblical Mt. Ararat: Two Identifications

68 Armen Petrosyan: Biblical Mt. Ararat: Two Identifications Biblical Mt. Ararat: Two Identifications ARMEN PETROSYAN Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Yerevan, Armenia Abstract: The biblical Ararat, mountain of landing of Noah’s Ark has two general identifications in the Armenian Highland: Mountain of Corduena (modern Cudi dağı) and Masis (Ararat, Ağrı dağı), situated respectively in the extreme south-east and extreme north- east of modern Turkey). The ancient sources actualized the first localization. Since the 12th century the second became more and more popular. The paper deals with the myths and legends associated with those mountains and the history of identification of the biblical Ararat. Ararat, the mountain of the landing of Noah’s Ark, has been identified in various locations, but up until now two main candidates persist: the mountain of Corduena and Masis. In the Hebrew Bible (Masoretic text) the mountains are called 'Arārāṭ, in the Greek translation (Septuagint) – Ararat, in Chaldean and Syrian (Peshitta) – Qardū, in Arabic – Qarda, and in Latin – “Mountains of Armenia”. Ararat is believed to be the Greek version of Hebrew 'RRṬ, i.e. Urartu (Piotrovsky 1944: 29; 1969: 13; Inglizian 1947: 5 ff., 63 ff; Musheghyan 2003: 4 ff.: Salvini and Salvini 2003; Marinković 2012). On the other hand, Ararat is almost identical to the Armenian term Ayrarat – the name of the central province of Armenia, with Mt. Masis at its center. However, Urartu and Ayrarat are two different geographical concepts. Ayrarat is the Armenian name of the region, which in Urartian sources is referred to as the land of Etiuni or Etiuhi (in the north of Urartu). -

The Pagan God Dagon

The Pagan God Dagon Preface: The pagan god, Dagon, is mentioned in only three passages in Scripture, and once in the Apocrypha. In all of those places, Dagon is associated with the Philistines and the city of Ashdod, a famous city of the Philistines. However, he appears to have been a universal god for a much wider group of peoples. Harold G. Stigers, who wrote one of the articles on Dagon for ZPEB, tells us that Dagon was a storm god from the upper Euphrates area and that conquerors from Mesopotamia brought Dagon into the Palestine and Syrian areas.1 Topics: Occurrences of Dagon in Scripture The Possible Meanings of Dagon from the Hebrew Canaanite Gods The Cities of Beth-dagon Charts: Vocabulary Chart 1. The proper noun, Dagon, is actually found very little in the Bible. a. When the Philistines had captured Samson (after Delilah had cut his hair), they offered sacrifices to their god Dagon in Judges 16:23. Most chronologies separate this incident from our context of I Sam. 5 by a mere 20 years. b. Dagon, the god of the Philistines, is found, obviously throughout our passage, which is I Sam. 5. It is found 11 times in this chapter. c. Dagon will only be mentioned one more time, and also very near this time period. When the Philistines take the bodies of Saul and his sons, they cut off the head of Saul and attached it to the temple of Dagon. I Chron. 10:10. The Philistines will be soundly defeated by David and we will hear of their god Dagon no more in Scripture. -

Flying Spirit a Success

The Official National Newsletter of the SAAF Association December 2020 1 Content SAAFA 75th Banquet P4 SAAF Association Well, here we are, at the end of a honours and year which for many of us can best be awards P5 described as having been an annus Military Attaché horribilis, the Latin term for “a terrible and Advisor year” that Queen Elizabeth famously Corps P7 brought into modern parlance at the Branch News P8 end of 1992. The year 2020 was meant to have been an eventful year The SAAF Association SAAFA National marked by many interesting and Outeniqua President Col Mike Louw exciting events that were planned. Branch However, besides the SAAFA 75 P12 Birthday Cocktail Function on 26 January and the SAAFA National Durban branch Banquet and Awards Evening held on 7 November, the year was proposal for rather eventless, other than facing the challenges brought about by hosting SAAFA congress 2021 the Covid pandemic. P15 he end of a year can be such an emotional time for many people. SAAFA Member T Wins Whether it was a good year or not so good year, one gets a feeling International for such as the year-end approaches. And with 2020 has been no Aviation Award P16 exception, we perhaps find ourselves counting down the days to 2021. A new year with new possibilities, where the problems of 2020 Christmas Truce can fade away. However, despite whatever happened over this of 1914 P17 past, we need to be thankful for the many blessings we encountered History of along the way, however big or small. -

Egyptian Myth and Legend

EGYPTIAN MYTH AND LEGEND Donald Mackenzie EGYPTIAN MYTH AND LEGEND Table of Contents EGYPTIAN MYTH AND LEGEND................................................................................................................1 Donald Mackenzie...................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................4 CHAPTER I. Creation Legend of Sun Worshippers............................................................................17 CHAPTER II. The Tragedy of Osiris....................................................................................................23 CHAPTER III. Dawn of Civilization.....................................................................................................30 CHAPTER IV. The Peasant who became King....................................................................................36 CHAPTER V. Racial Myths in Egypt and Europe...............................................................................45 CHAPTER VI. The City of the Elf God................................................................................................50 CHAPTER VII. Death and the Judgment..............................................................................................54