CZECH (With Slovak) 2020/2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Silence of Lorna

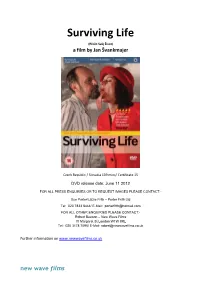

Surviving Life (Přežit Svůj Život) a film by Jan Švankmajer Czech Republic / Slovakia 109 mins/ Certificate 15 DVD release date: June 11 2012 FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES OR TO REQUEST IMAGES PLEASE CONTACT:- Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel: 020 7833 8444/ E-Mail: [email protected] FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT:- Robert Beeson – New Wave Films 10 Margaret St London W1W 8RL Tel: 020 3178 7095/ E-Mail: [email protected] Further information on www.newwavefilms.co.uk new wave films Surviving Life Director Jan Švankmajer Script Jan Švankmajer Producer Jaromír Kallista Co‐Producers Juraj Galvánek, Petr Komrzý, Vít Komrzý, Jaroslav Kučera Associate Producers Keith Griffiths and Simon Field Music Alexandr Glazunov and Jan Kalinov Cinematography Jan Růžička and Juraj Galvánek Editor Marie Zemanová Sound Ivo Špalj Animation Martin Kublák, Eva Jakoubková, Jaroslav Mrázek Production Design Jan Švankmajer Costume Design Veronika Hrubá Production Athanor / C‐GA Film CZECH REPUBLIC/SLOVAKIA 2010 ‐ 109 MINUTES ‐ In Czech with English subtitles CAST Eugene , Milan Václav Helšus Eugenia Klára Issová Milada Zuzana Kronerová Super‐ego Emília Došeková Dr. Holubová Daniela Bakerová Colleague Marcel Němec Antiquarian Jan Počepický Prostitute Jana Oľhová Janitor Pavel Nový Boss Karel Brožek Fikejz Miroslav Vrba SYNOPSIS Eugene (Václav Helšus) leads a double life ‐ one real, the other in his dreams. In real life he has a wife called Milada (Zuzana Kronerová); in his dreams he has a young girlfriend called Eugenia (Klára Issová). Sensing that these dreams have some deeper meaning, he goes to see a psychoanalyst, Dr. Holubova, who interprets them for him, with the help of some argumentative psychoanalytical griping from the animated heads of Freud and Jung. -

The Translation of Czech Literature in Taiwan and Mainland China

Compilation and Translation Review Vol. 12, No. 2 ( September 2019 ), 173 - 208 Images of Bohemia: The Translation of Czech Literature in Taiwan and Mainland China Melissa Shih-hui Lin “Bohemia” is the historically rich and traditional name of the Czech lands or Czechia (i.e., the Czech Republic, the latter being its current official name). This term may suggest to us a “romantic” image, perhaps a romantic atmosphere and wandering, carefree style, though it is a word that cannot be defined precisely. Or perhaps a specific ethnic group will first come to mind, and/or a piece of land in Eastern Europe. Even in our so-called era of globalization, there still remains a great “cultural distance” between Chinese culture and Eastern European culture. Literary translation is of course an important bridge between Chinese and Czech culture, even if the translation itself is inevitably influenced by cultural differences. These differences are absorbed into the translated content – either intentionally or unintentionally – and thus affect the reader’s understanding. This paper investigates the development of translations of Czech literary texts in Taiwan and Mainland China during three periods: the period before 1989, when the Soviet iron curtain collapsed; the late 1990s, when translations of Czech literature in simplified Chinese characters were being increasingly re-published in Taiwan; and our contemporary period, in which we have Czech literary translations in both Taiwan and Mainland China. This study also introduces and discusses the results of a questionnaire, one which focuses on the image of Bohemia in East Asia, and the Taiwanese people’s understanding of Czech literature. -

29 Th of the Countries of Central and Eastern Europe, Was Finally Brought Down

th n the fall of 1989, something happened that many never thought could happen: the IIron Curtain, the sphere of influence and control the Soviet Union maintained over many –29 of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, was finally brought down. Nowhere was that process of liberation more dramatic than in rd Czechoslovakia. Responding to a brutal po- lice suppression of a peaceful protest march, millions of Czechs and Slovaks took to their 23 streets, the final proof (if any were still needed) that the “people’s government” represented The Kind Revolution little more than those who ran it. Within months, Václav Havel, a dissident ` playwright who had become the best-known symbol of resistance to the Soviet-backed re- gime, was elected president of a new, multi-par- ty democracy. Czechoslovakia, which would soon split into separate Czech and Slovak enti- ties, was once again free to carve out its own October path, make its own mistakes, and establish the role of a small nation in the middle of Europe and a rapidly globalizing world. To celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Citizen Havel Velvet Revolution—so-called because of the ˇ impressive lack of violence that accompanied Citizen Havel / Obcanˇ Havel the toppling of the Communist government—this PaveL KouTeck‘Y anD MiroSLav JaneK, series presents some of the finest Czech films CzeCh rePuBLiC, 2008; 120M Chronicling the private and public life of dissi- made since 1989, including several internation- Designed by Frantisek Kast/SSS and Laura Blum. Pink Tank by David Cerny by Blum. Pink Tank and Laura Kast/SSS Frantisek Designed by dent playwright-turned-president václav havel, al prizewinners and box-office successes. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

A Film by Bohdan Sláma

ICE MOTHER A FILM BY BOHDAN SLÁMA 67-year old Hana is the good soul of her family. Every One day, while Hana is looking for Ivánek who sneaked week her sons come over with their wives and children for out, she finds a man, Broňa, floating at the riverside, unable to their family dinner. It is a family tradition not to be changed. move. She jumps in and helps him to get out of the icy water. Selfless, Hana takes care of the little Ivánek, who is not really Hana gets to know his elderly friends and suddenly she is cherishing his grandma’s help. She also supports her other included in a new social circle. Even little Ivánek is interested son with money everytime he asks for it – and he asks a lot. A in the funny quirky group of ice swimmers. warmhearted yet modest person, Hana continues to live alone in the old family house without changing a thing ever since Light-hearted Broňa, who lives in an old camper bus near her husband died a few years ago. She might need a helping the river, inspires Hana’s lust for life. They become lovers, hand but both her sons are too busy and too selfish to see it. but when she introduces him to her sons, the whole family is shocked. In a series of events and dark secrets, Hana has to stand up and start changing her life. Born in 1967 in Opava, Czech Republic, Bohdan Sláma studied film directing at Prague Film School FAMU. -

Jiří Menzel's Closely Watched Trains

CHAPTER 11 TRAINSPOTTING: JIŘÍ MENZEL’S CLOSELY WATCHED TRAINS A 1963 graduate of his country’s film school (FAMU, or Faculty of the Academy of Dramatic Arts), the Czech Jiří Menzel spent the next two years working as an actor and assistant director. His first motion picture as a director was a contribution to an anthology film titled Pearls of the Deep (1965), based on five short stories by Bohumil Hrabal remarkable for their concentration on the destinies of little people on the edges of society. (Evald Schorm, Jan Němec, Věra Chytilová, and Jaromil Jireš were the other contributors, making Pearls of the Deep a kind of omnibus of the Czech New Wave, also known as the Czech Renaissance.) Menzel’s first feature, his masterpiece Closely Watched Trains (1966), is also his chief claim to a firm place in the history of Czech cinema. This picture, adapted from a Hrabal work as well, received an Academy Award for Best Foreign-Language Film and was also the biggest box-office success of all the New Wave works in Czechoslovakia. As the Hrabal adaptations suggest, Menzel was influenced by Czech fiction writers rather than Western filmmakers. Except for Crime in a Nightclub (1968), his reverential parody of American musical comedy, his films prior to the Soviet invasion of 1968 are adaptations of novels or short stories by Czech authors. These include Capricious Summer (1967), from a novella by Vladislav Vančura; Hrabal’s Closely Watched Trains, “The Death of Mr. Baltisberger” (segment from Pearls of the Deep), and Larks on a String (1969); and Josef Skvorecký’s Crime at a Girls’ School (1965). -

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes

Title Call # Category Lang./Notes K-19 : the widowmaker 45205 Kaajal 36701 Family/Musical Ka-annanā ʻishrūn mustaḥīl = Like 20 impossibles 41819 Ara Kaante 36702 Crime Hin Kabhi kabhie 33803 Drama/Musical Hin Kabhi khushi kabhie gham-- 36203 Drama/Musical Hin Kabot Thāo Sīsudāčhan = The king maker 43141 Kabul transit 47824 Documentary Kabuliwala 35724 Drama/Musical Hin Kadının adı yok 34302 Turk/VCD Kadosh =The sacred 30209 Heb Kaenmaŭl = Seaside village 37973 Kor Kagemusha = Shadow warrior 40289 Drama Jpn Kagerōza 42414 Fantasy Jpn Kaidan nobori ryu = Blind woman's curse 46186 Thriller Jpn Kaiju big battel 36973 Kairo = Pulse 42539 Horror Jpn Kaitei gunkan = Atragon 42425 Adventure Jpn Kākka... kākka... 37057 Tamil Kakushi ken oni no tsume = The hidden blade 43744 Romance Jpn Kakushi toride no san akunin = Hidden fortress 33161 Adventure Jpn Kal aaj aur kal 39597 Romance/Musical Hin Kal ho naa ho 41312, 42386 Romance Hin Kalyug 36119 Drama Hin Kama Sutra 45480 Kamata koshin-kyoku = Fall guy 39766 Comedy Jpn Kān Klūai 45239 Kantana Animation Thai Kanak Attack 41817 Drama Region 2 Kanal = Canal 36907, 40541 Pol Kandahar : Safar e Ghandehar 35473 Farsi Kangwŏn-do ŭi him = The power of Kangwon province 38158 Kor Kannathil muthamittal = Peck on the cheek 45098 Tamil Kansas City 46053 Kansas City confidential 36761 Kanto mushuku = Kanto warrior 36879 Crime Jpn Kanzo sensei = Dr. Akagi 35201 Comedy Jpn Kao = Face 41449 Drama Jpn Kaos 47213 Ita Kaosu = Chaos 36900 Mystery Jpn Karakkaze yarô = Afraid to die 45336 Crime Jpn Karakter = Character -

The Czech Republic

THE CZECH ...CZECH IT OUT! REPUBLIC IN YOUR OWN BACKYARD NÁVRAT DIVOKÝCH KONÍ / THE CZECH RETURN OF THE WILD HORSES JAN HOŠEK 2011, 28MIN ROK ĎÁBLA / YEAR OF THE DEVIL The Central Asian Przewalski’s Horse is the very last PETR ZELENKA surviving wild horse species. The world learned of its 2002, 90MIN existence only in 1881 – but less than a hundred years REPUBLIC later it had already been driven to extinction in the Year of the Devil is a 2002 Czech “Mockumentary” wild, surviving only in the care of zoological gardens. film directed by Petr Zelenka. It stars musicians who act as themselves: Czech folk music band Čechomor, Extraordinary credit for the preservation of the IN YOUR OWN BACKYARD musicians & poets Jaromír Nohavica, Karel Plihal & Przewalski’s horse goes to Prague Zoo, which in British/NZ musician & composer Jaz Coleman. 1959 was charged with managing the international studbook for the species & which has bred over two It was awarded the Crystal Globe at the Karlovy Vary hundred foals. Under the leadership of the late Prof. International Film Festival & won the Findling Award Veselovský, a former director of Prague Zoo, the & the FIPRESCI Prize at the Cottbus Film Festival of Czech Republic became one of the leading organizers Showing at Dorothy Browns Cinema Buckingham St Arrowntown. Young East European Cinema in 2002. In 2003 it won of international transports of Przewalski’s horses back 6 Czech Lions, including Best Film, Best Director, Best For more information www.czechffqueenstown.nz. to their original homeland. Editing, & was nominated for 5 more, including Best Screenplay & Best Cinematography. -

The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897

THE GERMAN NATIONAL ATTACK ON THE CZECH MINORITY IN VIENNA, 1897-1914, AS REFLECTED IN THE SATIRICAL JOURNAL Kikeriki, AND ITS ROLE AS A CENTRIFUGAL FORCE IN THE DISSOLUTION OF AUSTRIA-HUNGARY. Jeffery W. Beglaw B.A. Simon Fraser University 1996 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of History O Jeffery Beglaw Simon Fraser University March 2004 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Jeffery Beglaw DEGREE: Master of Arts, History TITLE: 'The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897-1914, as Reflected in the Satirical Journal Kikeriki, and its Role as a Centrifugal Force in the Dissolution of Austria-Hungary.' EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Martin Kitchen Senior Supervisor Nadine Roth Supervisor Jerry Zaslove External Examiner Date Approved: . 11 Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without the author's written permission. -

Jan Švankmajer - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 2/18/08 6:16 PM

Jan Švankmajer - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 2/18/08 6:16 PM Jan Švankmajer From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jan Švankmajer (born 4 September 1934 in Prague) is a Jan Švankmajer Czech surrealist artist. His work spans several media. He is known for his surreal animations and features, which have greatly influenced other artists such as Tim Burton, Terry Gilliam, The Brothers Quay and many others. Švankmajer has gained a reputation over several decades for his distinctive use of stop-motion technique, and his ability to make surreal, nightmarish and yet somehow funny pictures. He is still making films in Prague at the time of Still from Dimensions of Dialogue, 1982 writing. Born 4 September 1934 Prague, Czechoslovakia Švankmajer's trademarks include very exaggerated sounds, often creating a very strange effect in all eating scenes. He Occupation Animator often uses very sped-up sequences when people walk and Spouse(s) Eva Švankmajerová interact. His movies often involve inanimate objects coming alive and being brought to life through stop-motion. Food is a favourite subject and medium. Stop-motion features in most of his work, though his feature films also include live action to varying degrees. A lot of his movies, like the short film Down to the Cellar, are made from a child's perspective, while at the same time often having a truly disturbing and even aggressive nature. In 1972 the communist authorities banned him from making films, and many of his later films were banned. He was almost unknown in the West until the early 1980s. Today he is one of the most celebrated animators in the world. -

Ten Propositions About Munich 1938 on the Fateful Event of Czech and European History – Without Legends and National Stereotypes

Ten Propositions about Munich 1938 On the Fateful Event of Czech and European History – without Legends and National Stereotypes Vít Smetana The Munich conference of 29–30 September 1938, followed by forced cession of border regions of Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany and subsequently also to Poland and Hungary, is unquestionably one of the crucial milestones of Czech and Czecho- slovak history of the 20th century, but also an important moment in the history of global diplomacy, with long-term overlaps and echoes into international politics. In the Czech environment, round anniversaries of the dramatic events of 1938 repeatedly prompt emotional debates as to whether the nation should have put up armed resistance in the autumn of 1938. Such debates tend to be connected with strength comparisons of the Czechoslovak and German armies of the time, but also with considerations whether the “bent backbone of the nation” with all its impacts on the mental map of Europe and the Czech role in it was an acceptable price for saving an indeterminate number of human lives and preserving material assets and cultural and historical monuments and buildings all around the country. Last year’s 80th anniversary of the Munich Agreement was no exception. A change for the better was the attention that the media paid to the situation of post-Munich refugees from the border regions as well as to the fact that the Czechs rejected, immediately after Munich, humanist democracy and started building an authori- tarian state instead.1 The aim of this text is to deconstruct the most widespread 1 See, for example: ZÍDEK, Petr: Po Mnichovu začali Češi budovat diktaturu [The Czechs started building a dictatorship after Munich]. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films,