A Review of the Health Effects of Stimulant Drinks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MONITORING FUTURE 2015 Overview

MONITORING the FUTURE NATIONAL SURVEY RESULTS ON DRUG USE 1975–2015 2015 Overview Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use Lloyd D. Johnston Patrick M. O’Malley Richard A. Miech Jerald G. Bachman John E. Schulenberg Sponsored by The National Institute on Drug Abuse at The National Institutes of Health MONITORING THE FUTURE NATIONAL SURVEY RESULTS ON DRUG USE 2015 Overview Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use by Lloyd D. Johnston, Ph.D. Patrick M. O’Malley, Ph.D. Richard A. Miech, Ph.D. Jerald G. Bachman, Ph.D. John E. Schulenberg, Ph.D. The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research Sponsored by: The National Institute on Drug Abuse National Institutes of Health This publication was written by the principal investigators and staff of the Monitoring the Future project at the Institute for Social Research, the University of Michigan, under Research Grant R01 DA 001411 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the sponsor. Public Domain Notice All material appearing in this volume is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied, whether in print or non-print media including derivatives, without permission from the authors. If you plan to modify the material, please contact the Monitoring the Future Project at [email protected] for verification of accuracy. Citation of the source is appreciated, including at least the following: Monitoring the Future, Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Recommended Citation Johnston, L. -

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU)

21.3.2013 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 80/1 II (Non-legislative acts) REGULATIONS COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 230/2013 of 14 March 2013 on the withdrawal from the market of certain feed additives belonging to the group of flavouring and appetising substances (Text with EEA relevance) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, submitted before that deadline for the only animal category for which those feed additives had been auth orised pursuant to Directive 70/524/EEC. Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, (4) For transparency purposes, feed additives for which no applications for authorisation were submitted within the Having regard to Regulation (EC) No 1831/2003 of the period specified in Article 10(2) of Regulation (EC) No European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 1831/2003 were listed in a separate part of the 2003 on additives for use in animal nutrition ( 1 ), and in Community Register of Feed Additives. particular Article 10(5) thereof, (5) Those feed additives should therefore be withdrawn from Whereas: the market as far as their use as flavouring and appetising substances is concerned, except for animal species and categories of animal species for which applications for (1) Regulation (EC) No 1831/2003 provides for the auth authorisation have been submitted. This measure does orisation of additives for use in animal nutrition and not interfere with the use of some of the abovemen for the grounds and procedures for granting such auth tioned additives according to other animal species or orisation. Article 10 of that Regulation provides for the categories of animal species or to other functional re-evaluation of additives authorised pursuant to Council groups for which they may be allowed. -

ENERGY DRINK Buyer’S Guide 2007

ENERGY DRINK buyer’s guide 2007 DIGITAL EDITION SPONSORED BY: OZ OZ3UGAR&REE OZ OZ3UGAR&REE ,ITER ,ITER3UGAR&REE -ANUFACTUREDFOR#OTT"EVERAGES53! !$IVISIONOF#OTT"EVERAGES)NC4AMPA &, !FTERSHOCKISATRADEMARKOF#OTT"EVERAGES)NC 777!&4%23(/#+%.%2'9#/- ENERGY DRINK buyer’s guide 2007 OVER 150 BRANDS COMPLETE LISTINGS FOR Introduction ADVERTISING EDITORIAL 1123 Broadway 1 Mifflin Place The BEVNET 2007 Energy Drink Buyer’s Guide is a comprehensive compilation Suite 301 Suite 300 showcasing the energy drink brands currently available for sale in the United States. New York, NY Cambridge, MA While we have added some new tweaks to this year’s edition, the layout is similar to 10010 02138 our 2006 offering, where brands are listed alphabetically. The guide is intended to ph. 212-647-0501 ph. 617-715-9670 give beverage buyers and retailers the ability to navigate through the category and fax 212-647-0565 fax 617-715-9671 make the tough purchasing decisions that they believe will satisfy their customers’ preferences. To that end, we’ve also included updated sales numbers for the past PUBLISHER year indicating overall sales, hot new brands, and fast-moving SKUs. Our “MIA” page Barry J. Nathanson in the back is for those few brands we once knew but have gone missing. We don’t [email protected] know if they’re done for, if they’re lost, or if they just can’t communicate anymore. EDITORIAL DIRECTOR John Craven In 2006, as in 2005, niche-marketed energy brands targeting specific consumer [email protected] interests or demographics continue to expand. All-natural and organic, ethnic, EDITOR urban or hip-hop themed, female- or male-focused, sports-oriented, workout Jeffrey Klineman “fat-burners,” so-called aphrodisiacs and love drinks, as well as those risqué brand [email protected] names aimed to garner notoriety in the media encompass many of the offerings ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER within the guide. -

Update on Emergency Department Visits Involving Energy Drinks: a Continuing Public Health Concern January 10, 2013

January 10, 2013 Update on Emergency Department Visits Involving Energy Drinks: A Continuing Public Health Concern Energy drinks are flavored beverages containing high amounts of caffeine and typically other additives, such as vitamins, taurine, IN BRIEF herbal supplements, creatine, sugars, and guarana, a plant product containing concentrated caffeine. These drinks are sold in cans and X The number of emergency bottles and are readily available in grocery stores, vending machines, department (ED) visits convenience stores, and bars and other venues where alcohol is sold. involving energy drinks These beverages provide high doses of caffeine that stimulate the doubled from 10,068 visits in central nervous system and cardiovascular system. The total amount 2007 to 20,783 visits in 2011 of caffeine in a can or bottle of an energy drink varies from about 80 X Among energy drink-related to more than 500 milligrams (mg), compared with about 100 mg in a 1 ED visits, there were more 5-ounce cup of coffee or 50 mg in a 12-ounce cola. Research suggests male patients than female that certain additives may compound the stimulant effects of caffeine. patients; visits doubled from Some types of energy drinks may also contain alcohol, producing 2007 to 2011 for both male a hazardous combination; however, this report focuses only on the and female patients dangerous effects of energy drinks that do not have alcohol. X In each year from 2007 to Although consumed by a range of age groups, energy drinks were 2011, there were more patients originally marketed -

Smokable Cocaine Markets in Latin America and the Caribbean a Call for a Sustainable Policy Response

Smokable cocaine markets in Latin America and the Caribbean A call for a sustainable policy response ideas into movement AUTHORS: Ernesto Cortés and Pien Metaal EDITOR: Anthony Henman DESIGN: Guido Jelsma - www.guidojelsma.nl COVER PHOTO: Man smoking crack pipe Colombia, L. Niño. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: This publication was made possible through the financial support of the Open Society Foundation (OSF) and the Global Partnership on Drug Policies and Development (GPDPD). GPDPD is a project implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH on behalf of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and under the political patronage of the Federal Government’s Drug Commissioner. The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of TNI and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the donors. PUBLICATION DETAILS: Contents of the report may be quoted or reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that the source of information is properly cited. TRANSNATIONAL INSTITUTE (TNI) De Wittenstraat 25, 1052 AK Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tel: +31-20-6626608, Fax: +31-20-6757176 E-mail: [email protected] www.tni.org/drugs @DrugLawReform Drugsanddemocracy Amsterdam, December 2019 2 | Smokable cocaine markets in Latin America and the Caribbean transnationalinstitute Contents Introduction 4 Methodological approach 6 The Substance(s) 8 Smokable cocaine in Cochabamba (Bolivia) in the early 1990s 9 Users 14 Impact on health 17 The Market 21 Harm Reduction experiences 25 Conclusions and Discussion 28 Policy Recommendations 29 Good Practices: examples from Brazil 30 Bibiography and references 32 International smokable cocaines working group 33 Endnotes 34 transnationalinstitute Smokable cocaine markets in Latin America and the Caribbean | 3 Introduction regions. -

Dietary Supplements: Enough Already!

Dietary Supplements: Enough Already! Top Ten Things to Know Rhonda M. Cooper‐DeHoff, Pharm D, MS, FACC, FAHA University of Florida Associate Professor of Pharmacy and Medicine Presenter Disclosure Statement No conflicts or commercial relationships to disclose Learning Objectives After this lecture you will be able to: Understand current usage and expenditure patterns for dietary supplements Recall US regulations surrounding dietary supplements Recognize how dietary supplements may affect efficacy of and interact with prescription drugs Promote patient safety by counseling patients on issues pertaining to dietary supplement use Audience Response I take (have taken) herbal / dietary supplements Audience Response I recommend (have recommended) herbal/ dietary supplements to my patients #1 Definition and Cost of Complimentary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Categories of CAM (NIH) •Group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, Definition practices and products that are not generally considered part of conventional medicine. Alternative Biologically Manipulative Mind‐body Energy Medical Based and Body‐ Techniques Medicine Based Systems Vitamins Approaches & Spiritual Biofield Acupunct. Minerals Massage Natural therapy Magnetic Chinese Products Meditative field Medicine •Plants (gingko) Chiropract medicine Relaxation Reiki Ayurveda Diets 1998 Expenditure on CAM Manipulative and Biologically Mind‐body Alternative Body‐Based Energy Medicine Based Techniques Medical Systems Approaches 1.5% of $34 total HCE Billion but 11% of OOP OOP NCAM 2007 -

St. John's Wort 2018

ONLINE SERIES MONOGRAPHS The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products Hyperici herba St. John's Wort 2018 www.escop.com The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medicinal Products HYPERICI HERBA St. John's Wort 2018 ESCOP Monographs were first published in loose-leaf form progressively from 1996 to 1999 as Fascicules 1-6, each of 10 monographs © ESCOP 1996, 1997, 1999 Second Edition, completely revised and expanded © ESCOP 2003 Second Edition, Supplement 2009 © ESCOP 2009 ONLINE SERIES ISBN 978-1-901964-61-5 Hyperici herba - St. John's Wort © ESCOP 2018 Published by the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP) Notaries House, Chapel Street, Exeter EX1 1EZ, United Kingdom www.escop.com All rights reserved Except for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review no part of this text may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the written permission of the publisher. Important Note: Medical knowledge is ever-changing. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment may be required. In their efforts to provide information on the efficacy and safety of herbal drugs and herbal preparations, presented as a substantial overview together with summaries of relevant data, the authors of the material herein have consulted comprehensive sources believed to be reliable. However, in view of the possibility of human error by the authors or publisher of the work herein, or changes in medical knowledge, neither the authors nor the publisher, nor any other party involved in the preparation of this work, warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they are not responsible for any errors or omissions or for results obtained by the use of such information. -

Sheet1 Page 1 Name of Drink Caffeine (Mg) 5 Hour Energy 60

Sheet1 Name of drink Size (mL) Caffeine (mg) 5 Hour Energy 60 Equivalent of a cup of coffee Amp Energy (Original) 710 213 Amp Energy (Original) 473 143 Amp Energy Overdrive 473 142 Amp Energy Re-Ignite 473 158 Amp Energy Traction 473 158 Bawls Guarana 473 103 Bawls Guarana Cherry 473 100 Bawls Guarana G33K B33R 296 80 Bawls Guaranexx Sugar Free 473 103 Beaver Buzz Black Currant Energy 355 188 Beaver Buzz Citrus Energy 355 188 Beaver Buzz Green Machine Energy 473 200 Big Buzz Chronic Energy 473 200 BooKoo Energy Citrus 710 360 BooKoo Energy Wild Berry 710 360 Cheetah Power Surge Diet 710 None? Frank's Energy Drink 500 160 Frank's Energy Drink Lime 250 80 Frank's Energy Drink Pineapple 250 80 Full Throttle Unleaded 473 141 Hansen's Energy Pro 246 39 Hardcore Energize Bullet Blue Rage 85.7 300 Hype Energy Pro (Special Edition) 355 114 Hype Energy MFP 473 151 Inked Chikara 473 151 Inked Maori 473 151 Jolt Endurance Shot 60 200 Jolt Orange Blast 695 220 Lost (Original) 473 160 Lost Five-O 473 160 Mini Thin Rush (6 Hour) 60 200 Monster (Original) 710 246 Monster Assault 473 164 Monster Energy (Original) 473 170 Monster Khaos 710 225 Monster Khaos 473 150 Monster M-80 473 164 Monster MIXXD 473 Monster Reduced Carb 473 140 NOS (Original) 473 200 NOS (Original)(Bottle) 650 343 NOS Fruit Punch 473 246.35 Premium Green Tea Energy 355 119 Premium Iced Tea Energy 355 102 Premium Pink Energy 355 120 Red Bull 250 80 Red Bull 355 113.6 Page 1 Sheet1 Red Rain 250 80 Rocket Shot 54 50 Rockstar Burner 473 160 Rockstar Burner 710 239 Rockstar Diet 473 160 -

Segmentacija Pivcev Energijskih Pijač V Sloveniji Glede Na Njihove Življenjske Stile

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Luka Krajnik Segmentacija pivcev energijskih pijač v Sloveniji glede na njihove življenjske stile Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2015 UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Luka Krajnik Mentor: izr. prof. dr. Samo Kropivnik Segmentacija pivcev energijskih pijač v Sloveniji glede na njihove življenjske stile Diplomsko delo Ljubljana, 2015 Hvala mentorju dr. Samu Kropivniku za pomoč in nasvete pri izdelavi te diplomske naloge. Hvala staršema, ki sta me že kot majhnega naučila, da je kdaj pa kdaj treba stisniti zobe. Hvala prijateljem za podporo, brez katere bi bilo poletje 2015 veliko težje. Hvala sodelavcem za podporo in razumevanje. Hvala Vida! Segmentacija pivcev energijskih pijač v Sloveniji glede na njihove življenjske stile Življenjski stili so eden izmed odsevov in tudi ”produktov” potrošniške družbe. Dolgo so bili pogojeni z družbenim statusom oziroma ekonomskim razredom, kateremu je nekdo pripadal, danes pa predstavljajo skupni imenovalec posameznikom in skupinam, ki dobrine, čas in prostor trošijo na podobne načine. Preko življenjskega stila posameznik pripoveduje svojo zgodbo sebi in svetu. Eden izmed pomembnih gradnikov življenjskega stila je simbolni kapital, katerega svojim izdelkom in tržnokomunikacijskim naporom v zajetni meri pripenja več milijard evrov vredna industrija energijskih pijač. V diplomski nalogi sem s pomočjo statistične analize primarnih podatkov uspešno podprl domnevo, da je slovenske pivce energijskih pijač na podlagi njihovih življenjskih stilov mogoče razdeliti v več med seboj različnih segmentov: tradicionalne borce, samozavestne srečneže in neobremenjene zmerneže. Ključne besede: življenjski stili, potrošništvo, energijske pijače, razvrščanje v skupine Lifestyle segmentation study of energy drink consumers in Slovenia Today lifestyles are considered as noticeable reflections and “products” of consumer societies. -

Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Marketing Unveiled

SUGAR-SWEETENED BEVERAGE MARKETING UNVEILED VOLUME 1 VOLUME 2 VOLUME 3 VOLUME 4 THE PRODUCT: A VARIED OFFERING TO RESPOND TO A SEGMENTED MARKET A Multidimensional Approach to Reduce the Appeal of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages This report is a central component of the project entitled “A Multidimensional Approach to Reducing the Appeal of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages (SSBs)” launched by the Association pour la santé publique du Québec (ASPQ) and the Quebec Coalition on Weight-Related Problems (Weight Coalition) as part of the 2010 Innovation Strategy of the Public Health Agency of Canada on the theme of “Achieving Healthier Weights in Canada’s Communities”. This project is based on a major pan-Canadian partnership involving: • the Réseau du sport étudiant du Québec (RSEQ) • the Fédération du sport francophone de l’Alberta (FSFA) • the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation (SRDC) • the Université Laval • the Public Health Association of BC (PHABC) • the Ontario Public Health Association (OPHA) The general aim of the project is to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages by changing attitudes toward their use and improving the food environment by making healthy choices easier. To do so, the project takes a three-pronged approach: • The preparation of this report, which offers an analysis of the Canadian sugar-sweetened beverage market and the associated marketing strategies aimed at young people (Weight Coalition/Université Laval); • The dissemination of tools, research, knowledge and campaigns on marketing sugar-sweetened beverages (PHABC/OPHA/Weight Coalition); • The adaptation in Francophone Alberta (FSFA/RSEQ) of the Quebec project Gobes-tu ça?, encouraging young people to develop a more critical view of advertising in this industry. -

Final Project a PROJECTON PEPSICO. STING ENERGY DRINK

Final Project A PROJECT ON PEPSI CO. STING ENERGY DRINK (2011) ------------------------------------------------- Submitted By: FFaarrhhaan Abbiid 11663322--110099000044 Ghulam Shabbir 1632-109007 MBA (Marketing) ------------------------------- Approved by: _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _ Dean Faculty of Marketing Project Supervisor Inner Title A PROJECT ON PEPSI CO. STING ENERGY DRINK A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE PIMSAT INSTITUTE OF HIGHER EDUCATION IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION (MARKETING) BY FARHAN ABID & GHULAM SHABBIR MASTER IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION FACULTY OF MARKETING, PIMSAT INSTITUE OF HIGHER EDUCATION, PAKISTAN 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS SSeerriiaall DDeessccrriippttiioonn PPaaggeNN oo.. CCeerrttiiffiiccaatteess vviiii--iixx Acknowledgements x DDeeddiiccaattiioonn xxii EExxeeccuuttiivveSS uummmmaarryy xxiiii CChhaapptteerNN oo.11 IInnttrroodduuccttiioon TTo EEnneerrggy DDrriinnkk 1133--1144 11..11 IInnggrreeddiieennttsOO fEE nneerrggyDD rriinnkk 1155--1188 11..22 EEffffeeccttss 1199--2200 11..33 AAtttteemmppttsTTo BBaa nn 2211 11..44 HHiissttoorryy 2222--2244 11..55 CCaaffffeeiinnaatteedAA llccoohhoolliicEE nneerrggyDD rriinnkkss 2255--2266 11..66 AAnnttii--EEnneerrggyDD rriinnkkss 2277 11..77 HHiiddddeenRR iisskks 2277--2288 CChhaapptteerNN oo.22 IInnttrroodduuccttiioonTT oPP eeppssii 2299--3300 22..11 CCoommppaannyOO vveerrvviieeww 3311--3322 22..22 ABB rriieefPP eeppssiHH iissttoorryy 3333--4400 22..33 MMiissssiioonn 4411 -

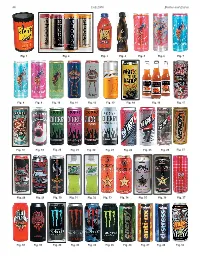

Bottles and Extras Fall 2006 44

44 Fall 2006 Bottles and Extras Fig. 1 Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 4 Fig. 5 Fig. 6 Fig. 7 Fig. 8 Fig. 9 Fig. 10 Fig. 11 Fig. 12 Fig. 13 Fig. 14 Fig. 16 Fig. 17 Fig. 18 Fig. 19 Fig. 20 Fig. 21 Fig. 22 Fig. 23 Fig. 24 Fig. 25 Fig. 26 Fig. 27 Fig. 28 Fig. 29 Fig. 30 Fig. 31 Fig. 32 Fig. 33 Fig. 34 Fig. 35 Fig. 36 Fig. 37 Fig. 38 Fig. 39 Fig. 40 Fig. 42 Fig. 43 Fig. 45 Fig. 46 Fig. 47 Fig. 48 Fig. 52 Bottles and Extras March-April 2007 45 nationwide distributor of convenience– and dollar-store merchandise. Rosen couldn’t More Energy Drink Containers figure out why Price Master was not selling coffee. “I realized coffee is too much of a & “Extreme Coffee” competitive market,” Rosen said. “I knew we needed a niche.” Rosen said he found Part Two that niche using his past experience of Continued from the Summer 2006 issue selling YJ Stinger (an energy drink) for By Cecil Munsey Price Master. Rosen discovered a company named Copyright © 2006 “Extreme Coffee.” He arranged for Price Master to make an offer and it bought out INTRODUCTION: According to Gary Hemphill, senior vice president of Extreme Coffee. The product was renamed Beverage Marketing Corp., which analyzes the beverage industry, “The Shock and eventually Rosen bought the energy drink category has been growing fairly consistently for a number of brand from Price Master. years. Sales rose 50 percent at the wholesale level, from $653 million in Rosen confidently believes, “We are 2003 to $980 million in 2004 and is still growing.” Collecting the cans and positioned to be the next Red Bull of bottles used to contain these products is paralleling that 50 percent growth coffee!” in sales at the wholesale level.