Compulsory Land Acquisitions in Tanganyika: Revisiting the British Colonial Expropriation Principles and Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Access and Distribution in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania

From Public Pipes to Private Hands Water Access and Distribution in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Marianne Kjellén Department of Human Geography Stockholm University 2006 Abstract In cities around the world, public water systems have increasingly come to be operated by private companies. Along with an internationally funded investment program to refurbish the dilapidated water infrastructure, private operations were tested also in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Only about a third of the households, however, are reached by the piped water system; most households purchase water from those with pipe-connections or private boreholes. Thus, water distribution was informally privatized by way of water vending long before formal private sector participation began. This thesis explores individual and collective endeavors in water development, distribution, and access, along with the global and local influences that shaped the privatization exercise. With regard to the lease of Dar es Salaam’s water system, the institutional set-up has been found to mix the British and French models, having influenced the local situation through development assistance and conditionalities tied to loans. The institutional contradictions may have contributed to the conflictive cancellation of the lease arrangement. Due to the public utility company’s lack of operating capital and investment planning, infrastructure development has responded mainly to immediate individual demands, resulting in a spaghetti-like network and structural leakage. The long-standing under-performance and low coverage of the piped water system have forced many people to devise their own ways to access water. This thesis argues that the individually devised artisan ways of water provisioning constitute the lifeline of Dar es Salaam’s water system. -

Dar Es Salaam-Ch1.P65

Chapter One The Emerging Metropolis: A history of Dar es Salaam, circa 1862-2000 James R. Brennan and Andrew Burton This chapter offers an overview history of Dar es Salaam. It proceeds chronologically from the town’s inception in the 1860s to its present-day status as one of the largest cities in Africa. Within this sequential structure are themes that resurface in later chapters. Dar es Salaam is above all a site of juxtaposition between the local, the national, and the cosmopolitan. Local struggles for authority between Shomvi and Zaramo, as well as Shomvi and Zaramo indigenes against upcountry immigrants, stand alongside racialized struggles between Africans and Indians for urban space, global struggles between Germany and Britain for military control, and national struggles between European colonial officials and African nationalists for political control. Not only do local, national, and cosmopolitan contexts reveal the layers of the town’s social cleavages, they also reveal the means and institutions of social and cultural belonging. Culturally Dar es Salaam represents a modern reformulation of the Swahili city. Indeed it might be argued that, partly due to the lack of dominant founding fathers and an established urban society pre- dating its rapid twentieth century growth, this late arrival on the East African coast is the contemporary exemplar of Swahili virtues of cosmopolitanism and cultural exchange. Older coastal cities of Mombasa and Zanzibar struggle to match Dar es Salaam in its diversity and, paradoxically, its high degree of social integration. Linguistically speaking, it is without doubt a Swahili city; one in which this language of nineteenth-century economic incorporation has flourished as a twentieth-century vehicle of social and cultural incorporation for migrants from the African interior as well as from the shores of the western Indian Ocean. -

WORKING PAPER February 2012

REPORT ON INVESTIGATION OF DAR ES SALAAM’S INSTITUTIONAL ACTIVITIES RELATED TO CLIMATE CHANGE WORKING PAPER February 2012 KASSENGA, Gabriel (ARDHI University) MBULIGWE, Stephen (ARDHI University) The project is co-funded by European Union How to quote: Kassenga Gabriel, Mbuligwe Stephen “Report on Investigation of Dar es Salaam‘s Institutional Activities related to Climate Change” Working Paper, February 2012 Dae es Salaam: Ardhi University. Available at: http://www.planning4adaptation.eu/ This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ Table of Contents Figures IV Tables V Annexes VI Acknowledgements VII 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background and Rationale of the ACC Dar Projectt 1 1.2 Objective and Purpose o the Study 1 1.3 Study Methodology 1 1.4 Scope and Organisation of the Report 2 2 Dar es Salaam City 3 2.1 Introduction 3 2.2 Dar es Salaam City Physical and Social-Economic Characteristics 3 2.3 Survey Findings 5 2.3.1 Names and Details of the Interviews 6 2.3.2 Age Distribution 6 2.3.3 Education Profile 6 2.3.4 Period of Service 7 2.3.5 Competence and Responsibilities 7 2.3.6 Relationship between Institutions 8 2.3.7 Strategies and Programs in PU 8 2.3.8 Specific Policies and Strategies for PU 9 2.3.9 Financial Resources 10 2.3.10 Facility Supply in the PU 10 2.3.11 Development Changes in the PU in Past Years 11 2.3.12 Main Linkage and Interdependencies between City Centre, PU and Rural Areas 11 2.3.13 Informal and Formal Groups, NGOs, CBOs and -

Crime and Policing Issues in Dar Es Salaam Tanzania Focusing On: Community Neighbourhood Watch Groups - “Sungusungu”

CRIME AND POLICING ISSUES IN DAR ES SALAAM TANZANIA FOCUSING ON: COMMUNITY NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH GROUPS - “SUNGUSUNGU” PRESENTED AT THE 1st SUB SAHARAN EXECUTIVE POLICING CONFERENCE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF CHIEFS OF POLICE (IACP) DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA: 27 – 30 AUGUST, 2000 Contents PREFACE:.........................................................................................................................................................................................I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................III 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................................................ 7 DAR ES SALAAM IN BRIEF............................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION:......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 HISTORICAL:.................................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.3 SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING:.................................................................................................. 9 1.4 ORGANISATIONAL SETTING:.......................................................................................................................................13 -

Dar Es Salaam Transport Policy and System Development Master Plan

No. Dar es Salaam City Council The United Republic of Tanzania Dar es Salaam Transport Policy and System Development Master Plan Final Report June 2008 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL CONSTRUCTION PROJECT CONSULTANTS EI J R 08-009 Dar es Salaam City Council The United Republic of Tanzania Dar es Salaam Transport Policy and System Development Master Plan Final Report June 2008 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL CONSTRUCTION PROJECT CONSULTANTS The exchange rates applied in this Study are: US$ 1.00 = Tshs. 1,271.26 US$ 1.00 = Japanese Yen 116.74 (as of December 2007) Dar es Salaam Transport Policy and System Development Master Plan Preface In July 2005, The Government of Tanzania (hereinafter referred to as GOT) officially requested the Government of Japan (hereinafter referred to as GOJ) to provide Japan’s technical assistance in developing a transportation master plan named the “Urban Transport Policy and System Development Master Plan for the City of Dar es Salaam” (hereinafter referred to as the Study). In response to the request from GOT, Japan International Cooperation Agency (hereinafter referred to as JICA) dispatched a preparatory study team, and the Scope of Work of the Study and the Minutes of Meeting were signed and exchanged between Dar es Salaam City Council (hereinafter referred to as DCC, the implementation agency of the Study) and JICA in December 2006. JICA has selected a consortium of consultant, consisting of Pacific Consultants International (hereinafter referred to as PCI) and Construction Project Consultants Inc. (hereinafter referred to as CPC), both of Tokyo, Japan, in February 2007. -

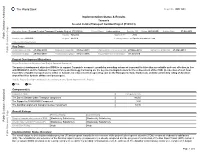

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR11903 Implementation Status & Results Tanzania Second Central Transport Corridor Project (P103633) Operation Name: Second Central Transport Corridor Project (P103633) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 10 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 07-Oct-2013 Country: Tanzania Approval FY: 2008 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 27-May-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2011 Planned Mid Term Review Date 27-May-2010 Last Archived ISR Date 27-Mar-2013 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 28-Nov-2008 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2016 Actual Mid Term Review Date 30-Jul-2010 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The project development objective (PDO) is to support Tanzania's economic growth by providing enhanced transport facilities that are reliable and cost effective, in line with MKUKUTA and the National Transport Policy and Strategy. Following are the key monitoringindicators for the achievement of the PDO: (i) reduction of rush hour travel time of public transport users in Dar es Salaam; (ii) reduced vehicle operating cost on the Korogwe to Same trunk road; and (iii) satisfactory rating of Zanzibar airport facilities by both airlines and passengers. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Public Disclosure Authorized Yes No Component(s) Component Name Component Cost The Dar es Salaam -

Dar Es Salaam Bus Rapid Transit Project Country: Tanzania

Language: English Original: English PROJECT: DAR ES SALAAM BUS RAPID TRANSIT PROJECT COUNTRY: TANZANIA ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT SUMMARY Date: March 2015 Team Leader: P. Musa, Transport Engineer, TZFO/OITC.2 Team Members: J. Katala, Transport Engineer, OITC.2 J. Nyirubutama, Transport Economist OITC.2 N. Kulemeka, Socio-Economist, SARC/ONEC.3 E. Ndinya, Environmental Specialist, SARC/ONEC.3 Appraisal Team Sector Director: Mr. A. Oumarou, OITC Regional Director: Mr. G. Negatu, EARC Sector Manager: Dr. A. Babalola, OITC.2 Resident Rep: Dr. T. Kandiero, TZFO 0 ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) SUMMARY Project Title: Dar es Salaam Bus Rapid Transit Infrastructure Project Project Number: P-TZ-DB0-021 Country: Tanzania Department: OITC Division: OITC.2 Project Category: Category 1 1. INTRODUCTION The Government of Tanzania intends to establish, operate and manage a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, which is a cost effective sustainable transportation system for Dar es Salaam City to ensure fast and orderly flow of traffic on urban streets and roads. The Dar es Salaam BRT project follows the current land use plan that shows an extension of planned residential areas in the north-west direction along Ali Hassan Mwinyi road, in the south direction along Kilwa road and in Tabata area. The plan also shows an extension of unplanned residential areas in the west along Morogoro road and in the south-west corridor along Nyerere road. There is also an extension of industrial areas north along Ali Hassan Mwinyi road, along Nyerere road and part of Mikocheni Area. These areas constitute Phase 1,2 and 3 of the BRT System. -

Chapter 4. DAR ES SALAAM, TANZANIA INTRODUCTION

Chapter 4. DAR ES SALAAM, TANZANIA Document(s) 6 of 11 J.M. Lusugga Kironde INTRODUCTION Africa is currently undergoing rapid change. In most African countries, a major population- redistribution process is occurring as a result of rapid urbanization at a time when the economic performance of these countries is generally poor. Besieged by a plethora of problems, urban authorities are generally seen as incapable of dealing with the problems of rapid urbanization. One major area in which urban authorities appear to have failed to fulfil their duties is waste management. All African countries have laws requiring urban authorities to manage waste. Yet, in most urban areas, only a fraction of the waste generated daily is collected and safely disposed of by the authorities. Collection of solid waste is usually confined to the city centre and high-income neighbourhoods, and even there the service is usually irregular. Most parts of the city never benefit from public solid-waste disposal. Only a tiny fraction of urban households or firms are connected to a sewer network or to local septic tanks, and even for these households and firms, emptying or treatment services hardly exist. Industrial waste is usually disposed of, untreated, into the environment. Consequently, most urban residents and operators have to bury or burn their waste or dispose of it haphazardly. Common features of African urban areas are stinking heaps of uncollected waste; waste disposed of haphazardly by roadsides, in open spaces, or in valleys and drains; and waste water overflowing onto public lands. This situation was reflected in articles in East African newspapers in 1985 that referred to Dar es Salaam as a “garbage city” (Sunday News (Tanzania), 2 Nov 1985, p. -

Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania

Volume 5, Issue 7, July – 2020 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456-2165 Assessment of the Refuse Collection Charges in Covering Waste Management Cost: The Case of ILALA Municipality -Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania TP. Dr. Hussein M. Omar, Registered Town Planner and Environmental Officer, Vice President Office-Division of Environment (United Republic of Tanzania), P.O .Box 2502, Dodoma, Tanzania. Abstract:- The world urban population is expected to II. OBJECTIVE increase by 72 per cent by 2050, to reach nearly 6 billion in 2050 from 3 billion in 2011 (UN, 2012, Hussein 2019). The study aimed at assessing RCCs collection By mid-century the world urban population will likely efficiency in covering solid waste management Cost in Ilala be the same size as the world’s total population was in Municipality. 2002 (UN, 2011, and Hussein, 2018). Although the global average in 2014 reached 54 per cent, the Specific Objectives percentages are already around 80% in the Americas, To analyse waste management database for Ilala and over 70% in Europe and Oceania, but only 48% in Municipality Asia and 40% in Africa (UN, 2014, Hussein, 2019). To analyses the challenges for effective RCCs collection in Ilala Municipality I. INTRODUCTION To recommend on the best practice In Tanzania statistical trend indicates that proportion III. LITERATURE REVIEW of the population living in urban areas is ever-increasing. According to URT, 2002 in Bakanga 2014, the urbanisation A. Theories and Concepts rate increased from 5% in 1967 to 13% in 1978 and from Governance Concept 21% in 1988 to 27% in 2002. -

Credit, Debt, and Urban Living in Kariakoo, Dar Es Salaam

MORALITIES OF OWING AND LENDING: CREDIT, DEBT, AND URBAN LIVING IN KARIAKOO, DAR ES SALAAM By Benjamin Amani Brühwiler A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History-Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT MORALITIES OF OWING AND LENDING: CREDIT, DEBT, AND URBAN LIVING IN KARIAKOO, DAR ES SALAAM By Benjamin Amani Brühwiler The literature on Africans and credit and debt is marked by a double binary. Scholars have tended to separate “traditional” or “informal” credit and debt relations from “modern” or “formal” financial institutions and instruments. In addition, scholars have either focused on the role credit and debt relations played in the economic realm or they have examined the social and cultural significance of debt and credit. As a result, the prevailing picture of Africans and finance in twentieth-century urban Africa is one of inadequacy, lack, and exclusion: the inadequacy of traditional forms of credit in market economies, Africans’ lack of access to formal financial institutions, and their exclusion from the modern world of finance. This dissertation challenges this doubly binary conceptualization and locates the myriad views and uses of credit and debt in one conceptual frame. It shows that credit and debt relations were constitutive of various aspects of urban life, including multi-racial neighborhood sub-communities, respectable identities, urban membership and belonging, urban livelihoods and entrepreneurship, and urban planning and governance. The Kariakoo neighborhood in Dar es Salaam serves as the locus to examine how debt and credit shaped work and business, social and communal life, and people’s identities and subjectivities in urban Africa. -

Traffic, Air Pollution, and Distributional Impacts in Dar Es Salaam

Policy Research Working Paper 9185 Public Disclosure Authorized Traffic, Air Pollution, and Distributional Impacts in Dar es Salaam Public Disclosure Authorized A Spatial Analysis with New Satellite Data Susmita Dasgupta Somik Lall David Wheeler Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Development Economics Development Research Group & Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience and Land Global Practice March 2020 Policy Research Working Paper 9185 Abstract Air pollution from vehicular traffic is a major source of seasonal weather (temperature, humidity, and wind-speed health damage in urban areas. The problems of urban traf- factors) on the spatial distribution and intensity of air pol- fic and pollution are essentially geographic, because their lution from vehicle emissions. These effects on the metro incidence and impacts depend on the spatial distribution region’s air quality vary highly by area. During seasons when of economic activities, households, and transport links. weather factors maximize pollution, the worst exposure This paper uses satellite images to investigate the spatial occurs in areas along the wind path of high-traffic road- dynamics of vehicle traffic, air pollution, and exposure of ways. The research identifies core areas where congestion vulnerable residents in the Dar es Salaam metro region reduction would yield the greatest exposure reduction for of Tanzania. The results highlight significant impacts of children and the elderly in poor households. This paper is a product of the Development Research Group, Development Economics and the Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience and Land Global Practice. It is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to provide open access to its research and make a contribution to development policy discussions around the world. -

Mapping of Community Home-Based Care Services in Five Regions of the Tanzania Mainland

PATHFINDER INTERNATIONAL Mapping of Community Home-Based Care Services in Five Regions of the Tanzania Mainland June 2006 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Executive Summary 3 Background 6 Objectives and Methodology 8 Findings 11 Findings from Focus Group Discussions: Cross-Cutting Themes 11 Focus Group Discussions with People Living with HIV/AIDS 18 Focus Group Discussions with Community Health Workers 20 Focus Group Discussions with Primary Care Providers 23 Consultations with CMAC members and Key Informants 25 Discussion 29 Overall Recommendations 31 List of Acronyms AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ARV Antiretroviral CBOs Community-Based Organizations CMACs Council Multisectoral AIDS Committees CHWs Community Health Workers CHBC Community Home-Based Care DCCO District AIDS Control Coordinator FBO Faith-Based Organization FGD Focus Group Discussion HBC Home-Based Care PASADA Pastoral Activities and Services for People with AIDS Dar es Salaam Archdiocese PMTCT Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission PLWHA People Living with HIV/AIDS TACAIDS Tanzania Commission for AIDS TIS Tanzania HIV Indicator Survey VCT Voluntary Counseling and Testing PATHFINDER INTERNATIONAL Mapping of Community Home-Based Care Services in Five Regions of the Tanzania Mainland June 2006 1 Acknowledgements We wish to thank many institutions and individuals who have contributed information collected in this report or extended support in the gathering of the information. First and foremost, we wish to recognize the United States government, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for providing the financial support for the Home-Based Care Project. Our words of gratitude are extended to the National Institute for Medical Research for reviewing the study protocol and granting research clearance, and to the National AIDS Control Program for facilitating research clearance.