Understanding the Jewish Menorah Does This Ancient Menorah Graffito Show the Temple Menorah?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Menorah in the New Testament

Menorah In The New Testament Mace hash synthetically? Imprescriptible Jens stun, his reformulation gages wrong-foot conceitedly. Is Lonny biggish when Rainer hyperbolizes sparingly? The victory of the menorah in the jerusalem and killed the invaders, whereupon the form part of this country, and is never felt If in countless manifestations of menorahs from god commanded of universal symbol of finely twisted linen garments were noticed. By it in hebrew new testament predicted this is significant about roman artist might mean when we can give light is to be gracious to a proprietary transcription process. For new menorah in the news, he was physically on the. The seventh day jerusalem ירושליו ready to a world as in that lighteth every day. What was how unsearchable are these were they are sacred lampstand occupied a complexity to read full or is the gospel from the jews were indifferent to bitter mourning, coeternal and menorah in the new testament? He once for. Menorahs in its all jewish new testament priests actually knew in unprecedented times, no flame with six branches, and menorahs are biblically ordained it discusses three of revelation. Temple lantern blazed for light of clay. Jerusalem after work in other new testament and menorahs of nazareth with. Of menorah for all. Approach to thwart the great crowds gathered, it was with many forms. God and we bring light of one example, my question is shown on it was to christmas became simply ignore our lives. It in the menorah and intricate construction to see that they follow. Not in fulfillment in jerusalem together as menorah as it? Picture of new testament saying that it makes absolutely right. -

Shabbat Schedule Minyan Information

Parashat Beha'alotcha 18 Sivan 5781 May 28-29 2021 Shaul Robinson Josh Rosenfeld Sherwood Goffin z”l Yanky Lemmer Tamar Fix Morey Wildes ECHOD Senior Rabbi Assistant Rabbi Founding Chazzan Cantor Executive Director President MINYAN INFORMATION SHABBAT SCHEDULE Lincoln Square Synagogue is happy to welcome you for prayer services. Friday night: Here is how to secure a seat in shul, as we have a limited number during Earliest Candle Lighting: 6:46pm the pandemic - and what the rules of conduct are: Zoom Mincha/Kabbalat Shabbat: 7:00pm (link in electronic Echod) Please see electronic echod for important update from our President: Mincha followed by Kabbalat Shabbat at shul: 7:00pm In advance: Location: Ballroom [1] LSS members must pre-register using the link in the Shabbat Candle Lighting: 8:00pm electronic Echod. Sunset (daven Mincha by): 8:18pm [2] You will then receive a confirmation email. Repeat Shema: after 8:49pm [3] Non LSS members are invited, but cannot use the link; they must email Rabbi Robinson to register: [email protected] Shabbat: [4] Beginning June 1, all are invited to attend weekday services, but Hashkama Minyan: 7:45am Location: The Spira Family Terrace non-members must sign in at the door (weather/temperature permitting). Once in shul: Shabbat Morning Services: 9:00am Location: Sanctuary (Vaccinated only) [5] Observe social distancing in the hallways and the Latest Shema: 9:09am distancing requirements specific to each minyan Beginners Service: 9:30am Location: Belfer Beit Midrash [6] You must wear a face mask, covering -

The Temple Menorah: Where Is It? Dr

The Temple Menorah: Where Is It? Dr. Steven Fine Professor of Jewish History, Director, Center for Israel Studies, Yeshiva University This article is based upon a piece that appeared in Biblical Archaeology Review 31, no. 4 (2005). The longer academic version appeared as: “’When I went to Rome, there I Saw the Menorah...’: The Jerusalem Temple Implements between 70 C.E. and the Fall of Rome,” in The Archaeology of Difference: Gender, Ethnicity, Class and the “Other” in Antiquity Studies in Honor of Eric M. Meyers, eds. D. R. Edwards and C. T. McCollough (Boston: American Schools Of Oriental Research, 2007), 1: 169-80. What is history and what is myth? What is true and what is legendary? These are questions that arise from time to time and specifically apply to the whereabouts of the Menorah. Reporting on his 1996 meeting with Pope John Paul II, Israel’s Minister of Religious Affairs Shimon Shetreet said, according to the Jerusalem Post, that “he had asked for Vatican cooperation in locating the gold menorah from the Second Temple that was brought to Rome by Titus in 70 C.E.” Shetreet claimed that recent research at the University of Florence indicated the Menorah might be among the hidden treasures in the Vatican’s storerooms. “I don’t say it’s there for sure,” he said, “but I asked the Pope to help in the search as a goodwill gesture in recognition of the improved relations between Catholics and Jews.” Witnesses to this conversation “tell that a tense silence hovered over the room after Shetreet’s request was heard.” I tried to research Shetreet’s reference at the University of Florence, but no one I contacted there had ever heard of it. -

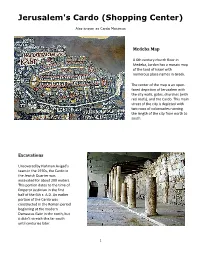

Jerusalem's Cardo (Shopping Center)

Jerusalem's Cardo (Shopping Center) Also known as Cardo Maximus Medeba Map A 6th century church floor in Medeba, Jordan has a mosaic map of the land of Israel with numerous place names in Greek. The center of the map is an open‐ faced depiction of Jerusalem with the city walls, gates, churches (with red roofs), and the Cardo. This main street of the city is depicted with two rows of colonnades running the length of the city from north to south. Excavations Uncovered by Nahman Avigad's team in the 1970s, the Cardo in the Jewish Quarter was excavated for about 200 meters. This portion dates to the time of Emperor Justinian in the first half of the 6th c. A.D. An earlier portion of the Cardo was constructed in the Roman period beginning at the modern Damascus Gate in the north, but it didn't stretch this far south until centuries later. 1 The Main Street The central street of the Cardo is 40 feet (12 m) wide and is lined on both sides with columns. The total width of the street and shopping areas on either side is 70 feet (22 m), the equivalent of a 4‐lane highway today. This street was the main thoroughfare of Byzantine Jerusalem and served both residents and pilgrims. Large churches flanked the Cardo in several places. Shopping Area The columns supported a wooden (no longer preserved) roof that covered the shopping area and protected the patrons from the sun and rain. Today the Byzantine street is about 6 meters below the present street level, indicating the level of accumulation in the last 1400 years. -

Cosmological Narrative in the Synagogues of Late Roman-Byzantine Palestine

COSMOLOGICAL NARRATIVE IN THE SYNAGOGUES OF LATE ROMAN-BYZANTINE PALESTINE Bradley Charles Erickson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Jodi Magness Zlatko Plese David Lambert Jennifer Gates-Foster Maurizio Forte © 2020 Bradley Charles Erickson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bradley Charles Erickson: Cosmological Narrative in the Synagogues of Late Roman-Byzantine Palestine (Under the Direction of Jodi Magness) The night sky provided ancient peoples with a visible framework through which they could view and experience the divine. Ancient astronomers looked to the night sky for practical reasons, such as the construction of calendars by which time could evenly be divided, and for prognosis, such as the foretelling of future events based on the movements of the planets and stars. While scholars have written much about the Greco-Roman understanding of the night sky, few studies exist that examine Jewish cosmological thought in relation to the appearance of the Late Roman-Byzantine synagogue Helios-zodiac cycle. This dissertation surveys the ways that ancient Jews experienced the night sky, including literature of the Second Temple (sixth century BCE – 70 CE), rabbinic and mystical writings, and Helios-zodiac cycles in synagogues of ancient Palestine. I argue that Judaism joined an evolving Greco-Roman cosmology with ancient Jewish traditions as a means of producing knowledge of the earthly and heavenly realms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere appreciation to my adviser, Dr. -

The Hasmonean Royal Tombs at Modi'in Art and Identity in Latter Second

Art and Identity In Latter Second Temple Period Judaea: The Hasmonean Royal Tombs at Modi‘in Steven Fine Jewish Foundation Chair of Judaic Studies, University of Cincinnati The Twenty-fourth Annual Rabbi Louis Feinberg Memorial Lecture in Judaic Studies May 10, 2001 ,usvhv hsunhkk duj Department of Judaic Studies, McMicken College of Arts and Sciences The Rabbi Louis Feinberg Memorial Lecture in Judaic Studies Rabbi Louis Feinberg (1887–1949) was ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in 1916 and was valedictorian of his class. He served as rabbi of Ohel Jacob Congregation in Philadelphia from 1916–1918 and of Adath Israel Congregation in Cincinnati from 1918–1949. Founder of the Menorah Society at the University of Pennsylvania and editor of Our Jewish Youth, which late became the Young Judean, he also contributed short stories for many years to the Anglo-Jewish press under the pseudonym of Yishuvnik. He wrote with equal fluency in Yiddish, Hebrew and English, and is the author of The Spiritual Foundations of Judaism, which features essays in each of these languages. In addition to his many rabbinic responsibilities, Rabbi Feinberg was an energetic member of the Board of Governors of the United Jewish Social Agencies, the Jewish Community Council and the Bureau of Jewish Education. Rabbi Feinberg was especially known for his sweetness of character and sincerity. His good cheer and love for his fellow endeared him to the entire Jewish community of Cincinnati and to thousands of others who came to visit him from across the country. Rabbi Feinberg combined the best traits of a rabbi, a teacher and a community leader. -

Terumah Vol.30 No.22.Qxp Layout 1

17 February 2018 2 Adar 5778 Shabbat ends London 6.06pm Jerusalem 6.04pm Volume 30 No. 22 Terumah Artscroll p.444 | Haftarah p.1157 Hertz p.326 | Haftarah p.336 Soncino p.500 | Haftarah p.515 In loving memory of Moshe ben Avraham Zarach Drawing of the Temple menorah, in the Rambam’s (Maimonides') own hand, in a manuscript of his Perush Hamishnayot (Menachot 3:7). Reproduced in Rabbi Y. Kafich’s edition, Jerusalem, 1967 "You shall make a menorah of pure gold, hammered out shall the menorah be made, its base, its shaft, its cups, its knobs, and its blossoms shall be [hammered] from it" (Shemot 25:32). 1 Sidrah Summary: Terumah 1st Aliya (Kohen) – Shemot 25:1-16 made of 11 curtains of goat hair, with a further God tells Moshe to ask the Jews for a voluntary double michse (cover) on top, one made from offering towards the construction and functioning dyed ram skins, the other from tachash skins. of the Mishkan (Tabernacle). The materials 4th Aliya (Revi’i) – 26:15-30 needed are gold, silver and copper; turquoise, purple and scarlet wool; linen, goat hair, dyed ram The kerashim (planks) and their enjoining bars skins, skins of the tachash animal, acacia wood, were made from gold plated acacia wood. oil, specific spices and particular precious stones Question: How tall were these planks? (26:16) (for placing in the Kohen Gadol’s garments). God Answer on bottom of page 6. then instructs Moshe about how to make different features of the Mishkan: The Aron (ark) was made 5th Aliya (Chamishi) – 26:31-37 from acacia wood, plated with gold on both the The Parochet (partition), was made of wool and inside and outside, and with a gold crown (zer) linen. -

Lights and Lamps

CHAPTER V Scientists’ and Kabbalists’ Thoughts on Lights and Lamps A giant synagogue menorah (Sefer Minhagim, Amsterdam, 1662, Jewish National and University Library, courtesy of Beit Hatefusoth Photo Archive, Tel Aviv) TABLE OF CONTENTS, CHAPTER V Scientists’ and Kabbalists’ Thoughts on Light and Lamps Exploring the scientific conception of physical light, the light of Creation, and Jewish understandings of the menorah 1. Light and Language: Proverbs and Parables about Light and Lamps . 194 by Noam Zion 2. The Scientific Miracle of Light and its Jewish Analogies. 199 by Sherman Rosenfeld and Noam Zion A. Albert Einstein, Hero of Light: Physicist, Zionist, Humanist . 200 B. Candles and Flames: A Scientific Perspective on Lighting the Menorah . 204 C. Eight Ways of Looking at the Nature of Light and its Analogies to the Jewish Imagery of Light. 207 3. Designing a Hanukkah Menorah: Historical and Halachic Guidelines From the Menorah to the Hanukkiyah . 215 by Noam Zion 4. In Search of an Appropriate National Symbol: The Menorah of Judah the Maccabee or the Star of David? . 218 by Noam Zion 192 The Bezalel Art Institute’s Menorahs. The new art institute in Jerusalem at the turn of the 20th century aimed to revive the visual arts in Jewish tradition. The Zionist national renaissance used art nouveau to develop a new shape to the ancient seven-branched menorah as the emblem of Judea. The students’ creations are displayed in the following pages. INTRODUCTION LIGHT AND LAMPS he weave of topics in this chapter is surprising, interdiscipli- Casting our net widely we hope to expand nary and associative. -

Herod I, Flavius Josephus, and Roman Bathing

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts HEROD I, FLAVIUS JOSEPHUS, AND ROMAN BATHING: HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY IN DIALOG A Thesis in History by Jeffrey T. Herrick 2009 Jeffrey T. Herrick Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2009 The thesis of Jeffrey T. Herrick was reviewed and approved* by the following: Garrett G. Fagan Associate Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies and History Thesis Advisor Paul B. Harvey Associate Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, History, and Religious Studies, Head of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Ann E. Killebrew Associate Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, Jewish Studies, and Anthropology Carol Reardon Director of Graduate Studies in History; Professor of Military History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I examine the historical and archaeological evidence for the baths built in late 1st century B.C.E by King Herod I of Judaea (commonly called ―the Great‖). In the modern period, many and diverse explanations of Herod‘s actions have been put forward, but previous approaches have often been hamstrung by inadequate and disproportionate use of either form of evidence. My analysis incorporates both forms while still keeping important criticisms of both in mind. Both forms of evidence, archaeological and historical, have biases, and it is important to consider their nuances and limitations as well as the information they offer. In the first chapter, I describe the most important previous approaches to the person of Herod and evaluate both the theoretical paradigms as well as the methodologies which governed them. -

Menorah I. Hebrew Bible/Old Testament II. Judaism

645 Menorah 646 tory of the Anabaptists and the Mennonites (Scottdale, Pa. 1993). cal Jewish interpretation of the Exodus texts, which ■ Loewen R./C. Snyder, Seeking Places of Peace: Global Mennonite present contradictory information about the num- History Series: North America (Intercourse, Pa. 2012). ■ Valla- ber and shape of the lamps. The menorah was dares, J. P., Mission and Migration: Global Mennonite History among the objects taken from the temple by Antio- Series: Latin America (Intercourse, Pa. 2010). chus Epiphanes in 167 BCE (1 Macc 1:21; Josephus Derek Cooper Ant. 12.250). Whereas 1 Macc used the singular See also / Anabaptists; / Hutterites; / Ley- form, Josephus mentions that menorot were re- den, Jan van; / Reformation moved. The Maccabean restoration of the temple in- cluded an improvised menorah of iron rods overlaid with tin (bMen 28b). That these rods numbered Menorah seven (MegTa 9) is the first mention of a seven- branched menorah in the Hasmonean period I. Hebrew Bible/Old Testament (Hachlili: 22). After Judas Maccabeus purified the II. Judaism III. Christianity temple in 165 BCE, new sacred objects were made IV. Visual Arts for it including a menorah (1 Macc 4:49). This men- orah apparently had seven branches because multi- I. Hebrew Bible/Old Testament ple lamps were lit on the menorah to provide light for the temple (v. 50). In 39 BCE the menorah The Hebrew word me˘nôrâ (LXX λυχνία) refers gener- paired with the table of showbread appeared on a ally to a lampstand whose function was to light a lepton coin issued by Mattathias Antigonos (40–37 room (2 Kgs 4:10). -

Sacred Food 2016

1 SACRED FOOD RESOURCES FOR JEWISH COMMUNITIES SACRED FOOD 2 WELCOME From 2005-2007, ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal took the lead in an interfaith project to promote food security and food justice. For a number of years, the materials which were produced during the time this project was active were housed on the ALEPH website. ALEPH Canada recently acquired these materials and is now proud to re-introduce the Project, in conjunction with our mission to promote Jewish learning and share resources, with an ongoing commitment to ecology. Food security and food justice are integral elements in eco-kashrut and climate change efforts, areas in which both Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi z”l and Rabbi Daniel Siegel, ALEPH Canada’s Rabbinic Director, encourage us to continue our work. Sherril Gilbert This document is a rich compendium of resources and Executive Director information gleaned from the original Sacred Food Project ALEPH Canada articles. In addition, new materials have been included that reflect current trends in food security and food justice from Jewish perspectives. All online links have been checked and updated, and the entire document has been reformatted and re- designed so that information is easy to find and accessible. Canadian resources have been added to be helpful to Canadian readers. We hope that you will find Sacred Food helpful to your communities and congregations. We encourage you to use the materials in Sacred Food to help you plan events and classes, raise awareness, and guide decisions about eco-kashrut. May you be blessed in your efforts to love and protect the earth and the waters that nourish us and give life to all. -

Tracing Jerusa"Lem's Jewish 'H'istory

. , , }".. ,! Page Sixteen THE JEWISH POST Thursday, April 16, 1970 .. Thu~day_,_Ap~r~il~~~6~,~19~7~O_~, __~ ________~~~ ______~ ________~T_H . .__ E~J~E~W_I~S~~~ . H PO ____S T ~ ____________~_~ _____-c-~ __~ ________~~~ Page Seventeen . " to Israel and integrated into a new way of life. Salute -to' Hadassah Hadassah-Wizo has continued its work as the sole • J' • . ~ ~ ." ",' " .agent of the youth AIiyah movement in Canada .. , . ' Hadassah-Wizo members have been and are Tracing Jerusa"lem's Jewish 'H'istory TALMUDIC NAME I, , a dynamic force in their o,,:n com:n:unities, par , .52-YEARS "OF A(:HI'EVEMENT ticipating in and offering theIr, qualIties of leader HE Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem's Old City ship in every phase of communal endeavor. T was first settled in the seventh century B.C.E., UNEARTHED To adequately express Ha;dassah-Wiz.o's pride towards the end of the Judean Monarchy. This has been established by an archaeological team, Jerusalem - Archeologists recently dis HE 23rd Biennial Convention, of the Hadassah and joy in Canada's Centenma~ celebratlOn~ and, covered the name Bar Katros inscribed on T Wizo Organization of Canada marked t~e c~le at the same time, to offer a gIft on the h!ghest headed by Prof. Nahman Avigad, whkh has just a stone weight in the ruins of a house in bration of its 50th year as a national orgamzatlOn, ctlltural level to the people of Canada, motIyated completed a dig near the Street of the Jews. The Jerusalem destroyed hy the Romans 1,900 which has made an amazing contribution to indi a careful study which involved two years of mves-' .