Nomination Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Religious Development of the Early German Settlers in "Greater Pennsylvania": the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia*

The Religious Development of the Early German Settlers In "Greater Pennsylvania": The Shenandoah Valley of Virginia* John B. Frantz The Pennsylvania State University Introduction Throughout much of the eighteenth century, the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia was the frontier. The first Europeans to settle there came from colonies to the north. They had the opportunity to create new culture in this sparsely inhabited area. Most of the Indians had aban- doned it, and Europeans from the Tidewater had not yet spread their plantations that far west. The Valley was an ideal location for innova- tion. Nevertheless, the early settlers brought with them their religious heritage and developed patterns and institutions for their spiritual nur- ture that were remarkably similar to those that they had known in their previous homes. Historiography Study of the religious development of the early German settlers has been underway for more than a century and a half One of the first accounts appeared in Samuel Kercheval's 1833 History of the Valley of Virginia.' A more detailed description is contained in John W Way- 1. Samuel Kercheval, The History of the Valley of Virginia 4th ed. (Strasburg Shenandoah Publish- ing House, 1925), originally published in 1833. The Religious Development of the Early German Settlers 67 land's History ofThe German Element of the Shenandoah Valley, published in 1907,2 some of which he included in his History of Shenandoah County that appeared twenty years later.3 Dedicated to Wayland and drawing on his work but going further is The Pennsylvania Germans of the Shenandoah Valley, the 1962 volume of the Pennsylvania German Folklore Society, by Elmer Lewis Smith, John G. -

Shenandoah National Park Project Virginia

SHENANDOAH NATIONAL PARK PROJECT VIRGINIA White Oak Canyon UNITED STATES SHENANDOAH NATIONAL PARK PROJECT DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary In the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammerer, Director national park in the Virginia section of the Blue Ridge Mountains was authorized by an act of Congress approv A ed May 22, 1926. The act specified that when title to 250,000 acres of a tract of land approved by the Secretary of the Interior should be vested in the United States, it would constitute a national park dedicated and set apart for the benefit and enjoyment of the people, and the Government would VIRGINIA STATE COMMISSION proceed with the installation of accommodations for visitors, ON the development of an adequate road and trail system, the CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT stocking of fishing streams, and the inauguration of an educa William E. Carson, Chairman tional service to acquaint the public with the historical back ground and natural beauty of this famous region. Upon the passage of the act, the State of Virginia, through its Commission on Conservation and Development, im mediately began the work of acquiring the money to purchase SHENANDOAH NATIONAL PARK PROJECT the necessary land. This was a tremendous undertaking as the approved area was made up of thousands of parcels of privately VIRGINIA owned land. Funds were raised through State appropriations, contributions from citizens of Virginia, and from outside sources. The work moved forward with all possible expediency until the period of general depression set in, and it became increasingly difficult to obtain funds. -

Route 11(Valley Pike/Valley Avenue) Corridor Study

DRAFT ROUTE 11 (VALLEY PIKE/VALLEY AVENUE) CORRIDOR STUDY FINAL DRAFT REPORT From Battle Park Drive to Renaissance Drive Date Prepared by Prepared for Logo Logo Route 11 (Valley Pike / Valley Avenue) Corridor Study From Battle Park Drive to Renaissance Drive Existing Conditions and Future Volumes Report August 6, 2018 | Final Draft Prepared for Prepared by WSP USA 277 Bendix Road, Suite 300 Virginia Beach, VA 23452 ROUTE 11 (VALLEY PIKE/VALLEY AVE) CORRIDOR STUDY | From Battle Park Drive to Renaissance Drive DRAFT Table of Contents 3.6 Future Traffic Volumes ................................................................................................................................... 18 3.7 Future No Build Background Improvements .................................................................................................. 18 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 3.8 Intersection Operations: Future 2030 No-Build Conditions ........................................................................... 18 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 4 Safety Analysis ........................................................................................................................................... 25 1.2 Purpose of Study .............................................................................................................................................. -

Comprehensive Plan

Acknowledgements: The Northern Shenandoah Valley Regional Commission would like to express its deep appreciation to all of the residents, workers, businesspersons, and community officials of the Town of Edinburg and Shenandoah County who contributed their time and knowledge to the development of the Town of Edinburg Comprehensive Plan. Edinburg Planning Commission: Richard Ritter, Chairman John W. Roller, Vice Chairman Steve Wood, Council Representative Kelly Day Joyce Giusto James Morris Richard Pence Joan Sharpe Henry Shirkey Mary Sigmond John Thompson Town of Edinburg Officials: Daniel Harshman, Mayor/ Town Manager Steve Wood, Vice- Mayor Clyde Beachy, Councilman Bradley Dellinger, Councilman Eloise Haun, Councilwoman Richard Wadkins, Councilman Fay Wymer,Councilwoman Doris F. Stover, Clerk-Treasurer Jay K. Wilk, Town Attorney Ronald L. Ross, Maintenance Supervisor Edinburg Board of Zoning Appeals Ronald Crabtree, Chairman Harold Hollar, Vice- Chairman Ronald Hoffman, Zoning Administrator David Alexander Carl Bright, Jr. James Morris This plan was prepared with technical assistance for the Northern Shenandoah Valley Regional Commission, acting as a consultant to the Town of Edinburg. The following staff members were most directly responsible for its content. Stephen W. Kerr, Executive Director Brian P. Henshaw, Community Planner Wendi L. Stine, GIS Specialist Marie G. Weaver, Administrative Assistant Karen T. Taylor, Administrative Assistant i General Thanks: NSVRC and the Town of Edinburg would like to publicly thank the Virginia -

Shenandoah at WAR

Shenandoah AT WAR If this Valley is lost, Virginia– Gen. is Thomas lost! J. “Stonewall” Jackson One story... a thousand voices. Visitors Guide to the Shenandoah Valley’s Civil War Story Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District Explore the National Historic District Other Areas By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher area by area... including Harpers Ferry, ground... There we took a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was Martinsburg, and thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher ground... There we took a stand and Winchester Charles Town Harpers Ferry including areas of Frederick and Clarke counties Page 40 for hours successfully repulsed Page 20 Third Winchester Signal Knob Winchester Battlefield Park including Middletown, Strasburg, and Front Royal By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Page 24 Brigade on higher ground... There we took a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher ground... There we took New Market including Luray and areas of Page County a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no Page 28 other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher ground... There we took a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher Rockingham ground.. -

W Inchester Occupied Winchester

SECOND WINCHESTER Winchester THIRD WINCHESTER FIRST WINCHESTER SECOND KERNSTOWN COOL SPRING FIRST KERNSTOWN CEDAR CREEK & BELLE GROVE CEDAR CREEK NATIONAL HISTORIC PARK Fighting commenced quite early this FISHER’S HILL Strasburg TOM’S BROOKE FRONT ROYAL Front Royal morning and cannonading has been going NEW MARKET BATTLEFIELD STATE HISTORICAL PARK NEW MARKET Luray on all day to the east of us on the Berryville New Market Road, but a mile or two from town... Harrisonburg Elkton Monterey CROSS KEYS McDowell PORT REPUBLIC MCDOWELL PIEDMONT Staunton Waynesboro inchester is in the northern, or lower, Shenandoah Valley. through the county courthouse, where their graffiti is still visible. The Formed by the Appalachians to the west and the Blue Ridge courthouse is now a museum open to the public, as is the house that Occupied Wto the east, the Valley shelters the Shenandoah River on its served as Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters the winter before his famous journey down to the Potomac at Harpers Ferry. 1862 Valley Campaign. Throughout the region, historic farms, homes, mills, and cemeteries, along with outstanding museums and interpreted The Valley’s natural corridor formed by the river also spawned the 19th Winchester sites, all help tell the powerful history and moving legacy of the war. century Valley Pike (modern-day US 11), along which both commerce and armies traveled. In contemporary times, Interstate 81 has Visitors can walk the battlefields at Kernstown, Cool Spring, and Second replaced the Pike as the principal transportation route, bringing both and Third Winchester and learn how Jackson, Robert E. Lee, Jubal Early, opportunities and challenges to the interpretation of Civil War history. -

Chapter 1: Regional Setting

Quick Facts— Created by General Assembly in 1836 Approximately 217 square miles in size 2010 Population: 37,439 5th smallest County in Virginia in land area 14th Highest Density Regional Setting / History Warren County Introduction Three factors in the County’s regional setting have greatly influenced growth and development. The first factor is its location in the Shenandoah Valley. For more than a century, the Valley has been noted for its beautiful mountains and clear streams and has attracted many tourists and seasonal guests. The Valley has been an important north-south transportation route since Indian times. A second regional setting factor influencing growth is the County’s location bordering two low passes over the Blue Ridge Mountains. Pioneer commerce from the Richmond and Hampton Roads areas passed through Chester and Manassas Gaps, across Warren County to distant markets. The early retail and industrial sectors of the economy developed from trans-shipping of manufactured goods and agricultural produce through the County. The third factor is the close proximity of Warren County to major cities. The distance to Washington D.C. is 70 miles; to Baltimore, 110 miles, and to Richmond, 135 miles. These and other eastern cities have been major market 2013 Comprehensive places for County produce and products, as well as major suppliers of Plan manufactured goods. Regional Setting / History Chapter 1 Regional Setting - History Regional Setting Warren County is located in the Shenandoah Valley of northwestern Virginia. It is bounded by Frederick and Clarke Counties on the north, by Fauquier and Rappahannock Counties on the east, by Page County on the south, and by Shenandoah County on the west. -

How to Use This Map-Guide

VIRGINIA CIVIL WAR TRAILS How to Use this Map-Guide This guide highlights more than 100 Civil War sites throughout the Shenandoah Valley and Southwest Virginia. Each site allows you to discover the epic and heartfelt stories of civilians and soldiers who experienced triumph and tragedy during the war. The suggested driving route will lead Travelers enjoy one of the colorful, you along many of interpretive markers along the trail. Virginia’s most scenic and historic roads. Enjoy one of the numerous walking tours available in many communities. Solicit the services of an outfitter for a once- in-a-lifetime adventure through the countryside. Shop at an antique or specialty shop, dine in a 19th century tavern or inn, or simply walk amid the serenity of a preserved battlefield, and let the stories you’ve discovered ignite your imagination as you envision how now peaceful landscapes were once the scenes of the deadliest battles known to man. For more detailed travel information, stop by any Virginia Welcome Center or local/regional visitor center or contact any of the attractions or visitor bureaus listed in this guide. For additional Civil War Trails information, visit www.CivilWarTrails.org. For more Virginia travel information, see www.Virginia.org. Cover painting from the collections of Fenton Historical Society, Jamestown, New York. Follow these signs to more than 1,500 Civil War sites. Johannes A. Oertel painting “The Virginia Turnpike,” popularly described as “Army Supply Train in the Shenandoah Valley.” WVA 81 Mosby’s Stephenson Depot -

Greenway Plan

The Central Shenandoah Valley Greenway Plan An Inventory and Natural Resource Assessment of the Central Shenandoah Region July 2004 The Central Shenandoah Valley Greenway Plan An Inventory and Natural Resource Assessment of the Central Shenandoah Region Covering: Augusta, Bath, Bridgewater, Broadway, Buena Vista, Craigsville, Dayton, Elkton, Glasgow, Goshen, Grottoes, Harrisonburg, Highland, Lexington, Monterey, Mount Crawford, Rockbridge, Rockingham, Staunton, Timberville and Waynesboro _________________________ Prepared by the Central Shenandoah Planning District Commission 112 MacTanly Place Staunton, VA 24401 July, 2004 The preparation of this plan was financed in part through a planning grant from the Virginia Department of Transportation’s Rural Transportation Planning Grant Program. The Central Shenandoah Planning District Commission is very thankful for the assistance of many people and organizations that contributed to and provided information for this document. They include: The Central Shenandoah Valley Greenway Committee Bill Blatter, City of Lexington Bill Kramer, Rockbridge Area Recreation Jean Clark, Lexington/Rockbridge Area Organization Tourism Development Roberta Lambert, Highland County Ronnie Coffey, Buena Vista Parks & Recreation Kyle O’Brien, Town of Broadway Sam Crickenberger, Rockbridge County Carolyn Pohowsky, Highland County Tim Crider, Town of Grottoes Chamber of Commerce George Dowrey, Town of Broadway John Sandridge, VDOT Paul Dressler, Bath County Jim Shaw, City of Waynesboro Brian Haluska, City of Waynesboro Tracey Shiflett, City of Buena Vista Drew Havens, Town of Glasgow Ron Sites, Augusta County Parks & Recreation Rhonda Henderson, Rockingham County Mike Solomon, Appalachian Trail Club Lee Hersch, City of Staunton Dave Soper, Milepost Zero Bob Holton, Town of Bridgewater Nancy Sorrells, Augusta County Hadley Jenner, Rockingham County Stacy Turner, City of Harrisonburg Organizations: Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation Upper Valley Regional Park Authority Friends of Blacks Run Virginia Dept. -

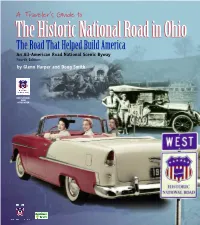

National Road User Guide/9.Qx5

A Traveler’s Guide to TThhee HHiissttoorriicc NNaattiioonnaall RRooaadd iinn OOhhiioo The Road That Helped Build America An All-American Road National Scenic Byway Fourth Edition by Glenn Harper and Doug Smith OHIO NATIONAL ROAD ASSOCIATION Welcome to the Historic National Road in Ohio, part of the road that helped build America. We are glad you have made the National Road and its many treasures your destination. The Ohio National Road is part of a six-state All-American Road, National Scenic Byway that stretches over 700 miles, from Baltimore through Maryland, Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, Indiana and Illinois to East St. Louis. We hope the information in this guide will enhance your journey through Ohio. What Are America’s Byways? nder the National Scenic Byways Program, the U.S. Secretary Uof Transportation recognizes certain roads as National Scenic Byways or All-American Roads based on their archaeological, cul - tural, historic, natural, recreational, and scenic intrinsic qualities. To be designated as a National Scenic Byway, a road must possess at W least one of the six intrinsic qualities and the distinctive character - istics must be recognized throughout the region. To receive an All- American Road designation, a road must possess multiple intrinsic qualities that are nationally significant and contain one-of-a-kind features that do not exist elsewhere. The road or highway must also TOLEDO be considered a destination unto itself. That is, the road must pro - CLEVELAND vide an exceptional traveling experience so recognized by travelers that they would make a drive along the highway a primary reason for their trip. -

Every Piece of Artillery, Every Wagon and Tent and Supporting Line of Troops Were in Easy Range of Our Vision

...every piece of artillery, every wagon and tent and supporting line of troops were in easy range of our vision. —Confederate Gen. John B. Gordon Observing from Signal Knob before the Battle of Cedar Creek October 1864 Signal Knob Area very close to succeeding in one of the largest battles west of the Blue Battlefields Ridge. The decisive Battle of Cedar Creek effectively ended the major Confederate war effort in the Shenandoah Valley. Front Royal May 23, 1862 Today, the road networks are much the same, and vestiges of these Jackson’s Valley Campaign military events have survived sufficiently to allow modern visitors to Fisher’s Hill retrace these famous campaigns. September 22, 1864 Sheridan’s Shenandoah Campaign Front Royal and the Cedar Creek battlefield each have visitor facilities Tom’s Brook that help explain Civil War events, while Belle Grove Plantation can October 9, 1864 tell you about life in the antebellum era. With information provided at Sheridan’s Shenandoah Campaign these places about walking trails, driving tours, and interpretive signage, visitors can walk parts of these and other battlefields and explore the Cedar Creek October 19, 1864 sites that tell this part of the Shenandoah Valley’s Civil War story. Sheridan’s Shenandoah Campaign Self-guided Tours Free printed driving tours of the Battle of Front Royal and the Battle of Fisher’s Hill are available at the visitor centers in this area and other Civil War sites. Walking tours of Front Royal and Strasburg are also available. A podcast tour of the Battle of Cedar Creek is available at nps.gov/cebe and at civilwartraveler.com/audio Go back quick and tell him that the Yankee Force is very small, one regiment of Maryland infantry...Tell him I know, for I went through the camps and got it out of an officer. -

Save 153 Acres at Second Winchester

SAVE 153 ACRES AT SECOND WINCHESTER “This battle of Winchester was one of the most perfect pieces of work the Army of Northern Virginia ever did.” - MAJ. ROBERT STILES valley CONFEDERATE ARTILLERYMAN shenandoahatwar.org In June of 1863, Confederate forces under Gen. Robert E. Lee were on the march toward Pennsylvania for their second invasion of the north. Leading the advance was the 2nd Corps commanded by Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell. As part of their advance, Ewell was given the task of clearing the Shenandoah Valley of all Union opposition. That Union opposition was in the CONFEDERATE fortified defenses of Winchester. On June 13th, Ewell’s 2nd Corps reached Winchester and LT. GEN. RICHARD EWELL went to work in clearing the way for the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia. Following two days of fighting south and east of Winchester, Union Maj. Gen. Robert Milroy was forced to abandon his forts and the town. On the night of June 14th, Milroy ordered his men to quietly move out of their defensive positions and head north using the darkness as their cover. The guns in the forts were spiked and all supplies destroyed. UNION MAJ. GEN. As Milroy’s army moved north, Confederate Maj. Gen. Edwards “Allegheny” Johnson anticipated ROBERT MILROY the attempted retreat and moved to cut it off. Moving his men east on the Berryville Pike, Johnson then turned north and marched his men along the Charlestown Road. The Charlestown Road lead his men toward Stephenson’s Depot and the Valley Pike, directly into the route of Milroy’s retreat.