Modernist and Postmodernist Arts of Noise, Part 1: from the European Avant-Garde to Contemporary Australian Sound Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resolution May/June 08 V7.4.Indd

craft Horn and Downes briefl y joined legendary prog- rock band Yes, before Trevor quit to pursue his career as a producer. Dollar and ABC won him chart success, with ABC’s The Lexicon Of Love giving the producer his fi rst UK No.1 album. He produced Malcolm McLaren and introduced the hitherto-underground world of scratching and rapping to a wider audience, then went on to produce Yes’ biggest chart success ever with the classic Owner Of A Lonely Heart from the album 90125 — No.1 in the US Hot 100. Horn and his production team of arranger Anne Dudley, engineer Gary Langan and programmer JJ Jeczalik morphed into electronic group Art Of Noise, recording startlingly unusual-sounding songs like Beat Box and Close To The Edit. In 1984 Trevor pulled all these elements together when he produced the epic album Welcome To The Pleasuredome for Liverpudlian bad-boys Frankie Goes To Hollywood. When Trevor met his wife, Jill Sinclair, her brother John ran a studio called Sarm. Horn worked there for several years, the couple later bought the Island Records-owned Basing Street Studios complex and renamed it Sarm West. They started the ZTT imprint, to which many of his artists such as FGTH were signed, and the pair eventually owned the whole gamut of production process: four recording facilities, rehearsal and rental companies, a publisher (Perfect Songs), engineer and producer management and record label. A complete Horn discography would fi ll the pages of Resolution dedicated to this interview, but other artists Trevor has produced include Grace Jones, Propaganda, Pet Shop Boys, Band Aid, Cher, Godley and Creme, Paul McCartney, Tina Turner, Tom Jones, Rod Stewart, David Coverdale, Simple Minds, Spandau Ballet, Eros Ramazzotti, Mike Oldfi eld, Marc Almond, Charlotte Church, t.A.T.u, LeAnn Rimes, Lisa Stansfi eld, Belle & Sebastian and Seal. -

Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository August 2016 Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E. Morley The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts © Briana E. Morley 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Morley, Briana E., "Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3991. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3991 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract There is a dark mythology surrounding the post-punk band Joy Division that tends to foreground the personal history of lead singer Ian Curtis. However, when evaluating the construction of Joy Division’s public image, the contributions of several other important figures must be addressed. This thesis shifts focus onto the peripheral figures who played key roles in the construction and perpetuation of Joy Division’s image. The roles of graphic designer Peter Saville, of television presenter and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and of photographers Kevin Cummins and Anton Corbijn will stand as examples in this discussion of cultural intermediaries and collaborators in popular music. -

Authenticity and Artifice in Rock and Roll: “And I Guess That I Just Don't Care”

Rock Music Studies ISSN: 1940-1159 (Print) 1940-1167 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrms20 Authenticity and Artifice in Rock and Roll: “And I Guess That I Just Don’t Care” Bernardo Alexander Attias To cite this article: Bernardo Alexander Attias (2016) Authenticity and Artifice in Rock and Roll: “And I Guess That I Just Don’t Care”, Rock Music Studies, 3:2, 131-147, DOI: 10.1080/19401159.2016.1155376 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19401159.2016.1155376 Published online: 21 Mar 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rrms20 Download by: [Bernardo Attias] Date: 21 March 2016, At: 23:50 Rock Music Studies, 2016 Vol. 3, No. 2, 131–147, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19401159.2016.1155376 Authenticity and Artifice in Rock and Roll: “And I Guess That I Just Don’t Care” Bernardo Alexander Attias Musicians, journalists and academics often hold up the Velvet Underground as the paragon of authenticity in rock music, and the band indeed portrayed itself this way from the outset. While much ink has been spilled explaining the original and authentic genius that is the Velvet Underground, an equally compelling case can be made that the band’s first album marked a turn towards insincerity and inauthen- ticity in popular music. This project emerges from the tension between these identi- ties. A close textual analysis of The Velvet Underground & Nico functions as an entry into theoretical arguments about truth and meaning in popular music. -

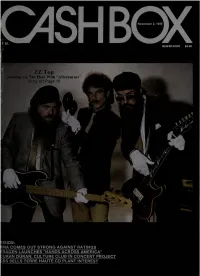

Cash Box NY Date, the Primary Sponsors of These Type of on What Could Have Been a Typical Album/Ticket Circulation NINA TREGUB

November 2, 1985 ZZ Top Turning Up The Heat With “Afterburner Story on Page 15 •« V 1 ' H Qf ^ J|| HBl Y C4SH BOX ^THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 21 — November 2, 1985 C4SHBQ< GUEST EDITORIAL GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARK ALBERT Corporate $$$$ Aid Artists & Promoters — Vice President and General Manager SPENCE BERLAND Manufacturer’s Next? Vice President By Rip Pelley J.B. CARMICLE Vice President Many years have passed since the American consumer tuned in the with major music stars. Many potential sponsors are still fence sitting DAVID ADELSON radio to laugh at a young comic who identified himself as “Bob because of the usual expensive fees inherent with these type of Managing Editor Pepsodent Hope." While Hope’s middle name may have changed from programs. Although these fees are usually justified, most advertisers ROBERT LONG "Pepsodent" to “Texaco,” consumers have never changed their cannot afford the high ticket sponsorship. willingness to identify products with the celebrities In fill the void for these of companies, record Director Black/Urban Marketing who endorse them. order to types Currently, the advertising industry, facing manufacturer’s can tap these organization’s JIMI FOX audience slippage and fragmentation in network products and retail outlets for use in national and Director Media Communications television advertising, has turned to event local new release campaigns. In turn, the Research sponsorship and targeted consumer marketing advertiser can participate in the airtime generated KEITH ALBERT, Manager campaigns to further reach today's mobile by these promotions, as well as potential DARRYL LINDSEY RON ROSENTHAL consumer. -

VIDEO and POP Paul Morley

May 1983 Marxism Today 37 VIDEO AND POP Paul Morley attention pop receives for multiples of wickedness, ridicule, discontent, eccentric ity, desire to thrive importantly in a genuinely popular context. Pop music can play a large part in the way numerous young people determine their right to desire and their need to question. It appeared that pop music's contem porary value was to be its creation or proposition of constant new values. Rock music — a period stretched from Elvis Presley to the last moment before The Sex Pistols coughed up Carry On Artaud — was easily appropriated by an establishment, the elegant apparatus of conservatism, that yearns for order. It was hoped that post-punk pop music, freed of the demands of over-excited hippies and usefully paranoiac, would evolve as some thing abstract, fluid, careering, irreverent, slippery, exaggerated — not on a revolu tionary mission, but non-static, not mean, a focus that supplies energy, as provocative and as changeable as essentially nostalgic twentieth century entertainment can be. A ringing variation. No destination, but a purpose. The video dumps us back into the most sinister part of the pop music game. In terms of pop as arousal the video takes us back to that moment before The Sex Pistols bawled louder than all the sur rounding banality. The moment of mundane disappointment. Some of us try an often brilliant best to resources can emerge that can help the The arrival, or at least the pop industry's prove to outsiders and cynics that pop audience release themselves from the misuse, of the video is a major reason, or music — what used to be known as rock unrelieving confinements of environment. -

Glam Rock by Barney Hoskyns 1

Glam Rock By Barney Hoskyns There's a new sensation A fabulous creation, A danceable solution To teenage revolution Roxy Music, 1973 1: All the Young Dudes: Dawn of the Teenage Rampage Glamour – a word first used in the 18th Century as a Scottish term connoting "magic" or "enchantment" – has always been a part of pop music. With his mascara and gold suits, Elvis Presley was pure glam. So was Little Richard, with his pencil moustache and towering pompadour hairstyle. The Rolling Stones of the mid-to- late Sixties, swathed in scarves and furs, were unquestionably glam; the group even dressed in drag to push their 1966 single "Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?" But it wasn't until 1971 that "glam" as a term became the buzzword for a new teenage subculture that was reacting to the messianic, we-can-change-the-world rhetoric of late Sixties rock. When T. Rex's Marc Bolan sprinkled glitter under his eyes for a TV taping of the group’s "Hot Love," it signaled a revolt into provocative style, an implicit rejection of the music to which stoned older siblings had swayed during the previous decade. "My brother’s back at home with his Beatles and his Stones," Mott the Hoople's Ian Hunter drawled on the anthemic David Bowie song "All the Young Dudes," "we never got it off on that revolution stuff..." As such, glam was a manifestation of pop's cyclical nature, its hedonism and surface show-business fizz offering a pointed contrast to the sometimes po-faced earnestness of the Woodstock era. -

How Joy Division Came to Sound Like Manchester: Myth and Ways of Listening in the Neoliberal City

Journal of Popular Music Studies, Volume 25, Issue 1, Pages 56–76 How Joy Division Came to Sound Like Manchester: Myth and Ways of Listening in the Neoliberal City Leonard Nevarez Vassar College Manchester, England, is among the most well-known cities today for the creation and celebration of popular music, thanks in no small part to the group Joy Division. Among the first bands to be associated with a postpunk aesthetic, Joy Division eschewed punk’syouthful rage and unrelenting din for an expansive, anthemic sound distinguished by its dynamic scope, machinic pulses, and by singer Ian Curtis’ssonorous baritone and existential lyrics. As the first significant band to sustain a career in Manchester, thus bypassing the music industry headquartered in London, Joy Division is also recognized as pioneering the DIY tradition that has famously characterized Manchester’s musical economy over the last four decades. The group didn’t achieve this alone; the role of Manchester label Factory Records is well documented, as, increasingly, is the foundation laid by the city’s networks of musicians, scene participants, and cultural institutions (see Crossley; Botta).´ Yet these local facts don’t quite explain the contemporary resonance of Joy Division’s Manchester roots for music fans and city boosters today. Perhaps more than any other Mancunian band, Joy Division are claimed to sound like Manchester, at least the Manchester of a certain era. That is, the group did not just originate from the late 1970s Manchester of deindustrialization, carceral housing estates, Thatcherism, and punk’s youthful refusal; nor do they simply illustrate a recurring Mancunian ethos of creative pluck and insouciant disregard for London’s cultural hegemony (Haslam, Manchester, England). -

2 to Be Somebody: Ambition and the Desire to Be Different

2 To Be Somebody: Ambition and the Desire to Be Different The context for difference This chapter aims to identify some of the bands that enjoyed chart success during the late 1970s and ’80s and identify their artistic traits by means of conversations with band members and those close to the bands. This chapter does not claim to be a definitive account or an inclusive list of innovative bands but merely a viewpoint from some of the individuals who were present at the time and involved in music, creativity and youth culture. Some of these individuals were in the eye of the storm while others were more on the periphery. However, common themes emerge and testify to the Scouse resilience identified in the previous chapter. Also, identifying objective truth is a difficult task, as one band member will often have a view of his band’s history that conflicts with that of other members of the same band. As such, it is acknowledged that this chapter presents only selective viewpoints. Trying something new: In what ways were the Liverpool bands creative and different? ‘Liverpool has always made me brave, choice-wise. It was never a city that criticized anyone for taking a chance.’ David Morrissey1 In terms of creativity, the theory underpinning this book which was stated in Chapter 1 is that successful Liverpool bands in the 1980s were different from each other and did not attempt to follow the latest local or national pop music trends. None of the bands interviewed falls into the categories of punk, disco or New Romantic, which were popular trends at the time. -

The Art of Noise the Best of the Art of Noise Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Art Of Noise The Best Of The Art Of Noise mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: The Best Of The Art Of Noise Country: Europe Released: 1988 Style: Leftfield, Downtempo, Synth-pop, Experimental, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1752 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1875 mb WMA version RAR size: 1745 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 426 Other Formats: MP4 MP3 AA MMF MP1 MIDI RA Tracklist Hide Credits Art Works 12" 1 Opus 4 2:00 2 Beat Box (Diversion One) 8:33 3 Moments In Love 7:00 4 Close (To The Edit) 5:41 Peter Gunn (The Twang Mix) 5 7:30 Featuring – Duane Eddy Paranoimia 6 6:40 Featuring – Max Headroom 7 Legacy 8:20 8 Dragnet '88 (From The Motion Picture Dragnet) 7:15 Kiss (The AON Mix) 9 8:09 Featuring – Tom Jones 10 Something Always Happens 2:28 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – China Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – China Records Ltd. Marketed By – Polydor Records Ltd. Distributed By – Polydor Records Ltd. Published By – Warner Bros. Music Ltd. Published By – Perfect Songs Ltd. Published By – Unforgettable Songs Ltd. Published By – RCA Music Ltd. Published By – Carlin Music Corp. Published By – Controversy Music Published By – Copyright Control Published By – BMG Music Publishing Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Zang Tuum Tumb Licensed From – Island Licensed From – ZTT Credits Composed By – Dudley* (tracks: 1 to 4, 6, 7, 10), Langan* (tracks: 1 to 4, 7, 10), Mancini* (tracks: 5), Jeczalik* (tracks: 1 to 4, 6, 7, 10), Morley* (tracks: 2 to 4), Prince (tracks: 9), Horn* (tracks: 2 to 4), Schumann* (tracks: 8) Design – Ryan Art Photography By [Sea Scape] – Paul Wakefield Producer, Arranged By – Anne Dudley (tracks: 1, 2, 5 to 10), Gary Langan (tracks: 1, 2, 5 to 7, 10), J. -

Celebrity, Gender, Desire and the World of Morrissey

" ... ONLY IF YOU'RE REALLY INTERESTED": CELEBRITY, GENDER, DESIRE AND THE WORLD OF MORRISSEY Nicholas P. Greco, B.A., M.A. Department of Art History & Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal March 2007 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright © Nicholas P. Greco 2007 Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-32186-7 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-32186-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell th es es le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

MINIMAL VIOLENCE Killer Tunes

573 DJMAG.COM LIVING & BREATHING DANCE MUSIC! DJMAG.COM EVERYBODY IN THE PLACE! HOLD TIGHT WITH THE OLD SKOOL ORIGINALS CREDIT TO THE EDIT 50 YEARS OF CUT & PASTE RUNNING * MUSIC BACK WITH TONY HUMPHRIES * CLUBS MIDLAND’S PERFECT MIX * TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY tINI & HER GANG TAKE IBIZA * SHARAM BACK TO THE UNDERGROUND BATTLE OF THE DECKS! INDUSTRY-STANDARD PLAYERS GO HEAD-TO-HEAD Charlotte ALL THE NOMINEES PROFILED! No. 573 de Witte September 2017 techno’s next-gen superstar VOTE NOW! No.573 September 2017 £4.95 £4.95 JULIA GOVOR, MARTIN SOLVEIG, JAY CLARKE, WALKER & ROYCE, DOC DANEEKA, BLONDES PLUS: HOUSEKEEPING, ART OF NOISE, GERD JANSON, HAUSCHKA, NOSAJ THING & MORE cover_1.indd 1 18/08/2017 14:02 THANKS FOR YOUR SUPPORT WWW.AFROJACK.COM Untitled-1 1 16/06/2017 12:40 DJMag2017_UK-1_v1.indd 1 16-06-17 10:17 CONTENTS 026 BORN IDENTITY Since adopting her real name, Charlotte de Witte has become the new face of techno. We head to Brussels to fi nd out what makes her tick... Cover shot: MARIE WYNANTS FEATURES 120 ELECTRIC CASTLE 119 FARR FESTIVAL 032 PART OF THE GANG! We catch up with tINI to get the low- down on all things Ibiza... 036 COOL RUNNINGS Legendary DJ, Tony Humphries, chats about his new Running Back comp... 042 CLOSE TO THE EDIT 50 years deep and the edit scene is bigger than ever, DJ Mag investigates... 049 PITCH PERFECT 036 TONY HUMPHRIES Graded boss Midland chats self- acceptance and living up to the hype... 055 BACK TO THE ROOTS Sharam discusses the ever-changing industry and his own career moves.. -

Billy Joel 50 Mi WHAT's the COLOUR of MONEY? 5 7 Nu Shooz Atlantic A9446(T) OE BM Hollywood Beyond WEA YZ 76(T)

I I I 5 •SINGLES MUSIC WEEK Compiled by Gallup for the BPI, Music Week and BBC, based on a sample of 250 record outlets. l*siRecords to be featured on this week's Top of the Pops Nol 2 hiP,,LA nDON'T PREACH 0 53 59 BORROWED LOVE Sire W8636(T) The S.O.S. Band Tabu (T)A 7241 THE EDGE OF HEAVEN 54 54 JOE 90 (Theme)/CAPTAIN SCARLET 2 Wham! Epic FIN(T) 1 Barry Gray Orchestra PRT 7PX 354 (12 —128P 354) MY FAVOURITE WASTE OF TIME CC 49 DON'T LET LOVE GET YOU DOWN 3 3Owen Paul tge'doe. Epic )TlA7125 'eye, Archie Bell &The Drells Portrait (T)A7254 HAPPY HOUR 5A 7, GOING DOWN TO LIVERPOOL 3 4 The Housemartins Go! Discs GOD(X) 11 `dOE Bangles CBS (T) A7255 TOO GOOD TO BE FORGOTTEN 57 34 THE TEACHER o 5 Amazulu Island (12)15 284 1 Big Country Mercury/Phonogram BIGC(X) 2 LET'S GO ALL THE WAY 58 iffl CALLING ALL THE HEROES 6 23 Sly Fox Capitol (12)CL 403 iridi It Bites Virgin VS 872(12) ICAN'T WAIT G Billy Joel 50 mi WHAT'S THE COLOUR OF MONEY? 5 7 Nu Shooz Atlantic A9446(T) OE BM Hollywood Beyond WEA YZ 76(T) VENUS co LISTEN LIKE THIEVES 9 8 , 60 Bananarama 140 London NANA 10 (12 .— NANX 10) INXS Mercury/Phonogram INXS 6(12) 9 8 NEW BEGINNING (Mamba Seyra) 61 63 I WOULDN'T LIE Bucks Fizz Polydor POSP(X) 794 Yarbrough &Peoples Total Experience/RCA FB 49841 (12 — FT 49842) DO YA DO YA (WANNA PLEASE ME) 42 THE CHICKEN SONG O 10 12 Samantha Fox Jive FOXY (T) 2 (A) 62 Spitting Image Virgin SPIT 1(12) MINE ALL MINE/PARTY FREAK 11 HUNTING HIGH AND LOW (REMIX) 63 56 A-Ha Warner Brothers W6663M Cathflow Club/Phonogram JAB(X) 30 (BANG ZOOM) LET'S GO GO al• Cooltempo/ NEW STRAIGHT FROM THE HEART 12 18 the Real Roxanne with Hitm anHowie Ter Chrysalis COOL(X) 124 64 Bryan Adams A&M AM(Y) 322 IT'S 'ORRIBLE BEING IN LOVE (WHEN YOU'RE 81/2) OLUTION TO) THE PROBLEM 13 19 65 66 S Claire and Friends BBC RESL 189 (12 ,— 12R51.