Draft Cert Opp 10-4 Reedy Edits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Independent Auditor's Limited Assurance Report of Old Mutual Unit Trust Managers (RF) (Pty) Ltd (The “Manager”)

KPMG Inc 4 Christiaan Barnard Street, Cape Town City Centre, Cape Town, 8000, PO Box 4609, Cape Town, 8001, South Africa Telephone +27 (0)21 408 7000 Fax +27 (0)21 408 7100 Docex 102 Cape Town Web http://www.kpmg.co.za/ Independent Auditor's Limited Assurance Report of Old Mutual Unit Trust Managers (RF) (Pty) Ltd (the “Manager”) To the unitholders of Old Mutual Core Conservative Fund We have undertaken our limited assurance engagement to determine whether the attached Schedule IB ‘Assets of the Fund held in compliance with Regulation 28’ at 31 December 2020 (the “Schedule”) has been prepared in terms of the requirements of Regulation 28 of the Pension Funds Act of South Africa (the “Regulation”) for Old Mutual Core Conservative Fund (the “Portfolio”), as set out on pages 4 to 39. Our engagement arises from our appointment as auditor of the Old Mutual Unit Trust Managers (RF) (Pty) Ltd and is for the purpose of assisting the Portfolio’s unitholders to prepare the unitholder’s Schedule IB ‘Assets of the Fund held in compliance with Regulation 28’ in terms of the requirements of Regulation 28(8)(b)(i). The Responsibility of the Directors of the Manager The Directors of the Manager are responsible for the preparation of the Schedule in terms of the requirements of the Regulation, and for such internal control as the Manager determines is necessary to enable the preparation of the Schedule that is free from material misstatements, whether due to fraud or error. Our Independence and Quality Control We have complied with the independence and other ethical requirements of the Code of Professional Conduct for Registered Auditors issued by the Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors (IRBA Code), which is founded on fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality and professional behaviour. -

Summary of Investments by Type

COMMON INVESTMENT FUNDS Schedule of Investments September 30, 2017 SUMMARY OF INVESTMENTS BY TYPE Cost Market Value Fixed Income Investments $ $ Short-term investments 27,855,310 27,855,310 Bonds 173,219,241 174,637,768 Mortgage-backed securities 29,167,382 28,915,537 Emerging markets debt 9,619,817 11,462,971 Bank loans - high income fund 23,871,833 23,908,105 Total Fixed Income Investments 263,733,583 266,779,691 Equity-Type Investments Mutual funds Domestic 9,284,694 13,089,028 International 18,849,681 21,226,647 Common stocks Domestic 149,981,978 192,057,988 International 225,506,795 259,856,181 Total Equity-Type Investments 403,623,148 486,229,844 Alternative Investments Funds of hedge funds 38,264,990 46,646,700 Real estate trust fund 6,945,440 10,204,969 Total Alternatives Investments 45,210,430 56,851,669 TOTAL INVESTMENTS 712,567,160 809,861,204 Page 1 of 34 COMMON INVESTMENT FUNDS Schedule of Investments September 30, 2017 SUMMARY OF INVESTMENTS BY FUND Cost Market Value Fixed Income Fund $ $ Short-term investments 6,967,313 6,967,313 Bonds 140,024,544 141,525,710 Mortgage-backed securities 27,878,101 27,642,277 Emerging markets debt 9,619,817 11,462,971 Bank loans - high income fund 23,871,833 23,908,105 208,361,608 211,506,377 Domestic Core Equity Fund Short-term investments 4,856,385 4,856,385 Common stocks 131,222,585 167,989,561 Futures - 19,895 Private placement 4,150 4,150 136,083,120 172,869,991 Small Cap Equity Fund Short-term investments 2,123,629 2,123,629 Mutual funds 9,284,694 13,089,028 Common stocks 18,755,243 -

Ctbc Financial Holding Co., Ltd. and Subsidiaries

1 Stock Code:2891 CTBC FINANCIAL HOLDING CO., LTD. AND SUBSIDIARIES Consolidated Financial Statements With Independent Auditors’ Report For the Six Months Ended June 30, 2019 and 2018 Address: 27F and 29F, No.168, Jingmao 2nd Rd., Nangang Dist., Taipei City 115, Taiwan, R.O.C. Telephone: 886-2-3327-7777 The independent auditors’ report and the accompanying consolidated financial statements are the English translation of the Chinese version prepared and used in the Republic of China. If there is any conflict between, or any difference in the interpretation of the English and Chinese language independent auditors’ report and consolidated financial statements, the Chinese version shall prevail. 2 Table of contents Contents Page 1. Cover Page 1 2. Table of Contents 2 3. Independent Auditors’ Report 3 4. Consolidated Balance Sheets 4 5. Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income 5 6. Consolidated Statements of Changes in Stockholder’s Equity 6 7. Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows 7 8. Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements (1) History and Organization 8 (2) Approval Date and Procedures of the Consolidated Financial Statements 8 (3) New Standards, Amendments and Interpretations adopted 9~12 (4) Summary of Significant Accounting Policies 12~39 (5) Primary Sources of Significant Accounting Judgments, Estimates and 40 Assumptions Uncertainty (6) Summary of Major Accounts 40~202 (7) Related-Party Transactions 203~215 (8) Pledged Assets 216 (9) Significant Contingent Liabilities and Unrecognized Contract 217~226 Commitment (10) Significant Catastrophic Losses 227 (11) Significant Subsequent Events 227 (12) Other 227~282 (13) Disclosures Required (a) Related information on significant transactions 283~287 (b) Related information on reinvestment 287~289 (c) Information on investment in Mainland China 289~290 (14) Segment Information 291 KPMG 11049 5 7 68 ( 101 ) Telephone + 886 (2) 8101 6666 台北市 信義路 段 號 樓 台北 大樓 68F., TAIPEI 101 TOWER, No. -

Chapter 2 Hon Hai/Foxconn: Which Way Forward ?

Chapter 2 Hon Hai/Foxconn: which way forward ? Gijsbert van Liemt 1 1. Introduction Hon Hai/Foxconn, the world's leading contract manufacturer, assembles consumer electronics products for well-known brand-names. It is also a supplier of parts and components and has strategic alliances with many other such suppliers. Despite its size (over a million employees; ranked 32 in the Fortune Global 500) and client base (Apple, HP, Sony, Nokia), remarkably little information is publicly available on the company. The company does not seek the limelight, a trait that it shares with many others operating in this industry. Quoted on the Taiwan stock exchange, Hon Hai Precision Industry (HHPI) functions as an ‘anchor company’ for a conglomerate of companies. 2 As the case may be, HHPI is the sole, the majority or a minority shareholder in these companies and has full, partial or no control at all. Many subsidiaries use the trade name Foxconn and that is why this chapter refers to the company as Hon Hai/Foxconn. Among its many subsidiaries and affiliates are Ambit Microsystems, Cybermart, FIH Mobile, Fu Taihua Industrial, Hong Fujin Precision and Premier Image. After a near hundredfold increase in sales in the first decade of this century Hon Hai/Foxconn's sales growth slowed down drastically. The company is facing several challenges: slowing demand growth in its core (electronics) business; a weakening link with Apple, its main customer; rising labour costs and a more assertive labour force in China, its main production location; and pressure from its shareholders. 1. Copyright 2015 Gijsbert van Liemt. -

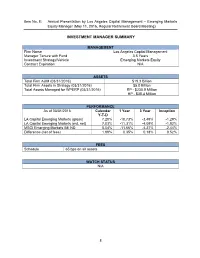

Investment Manager Summary

Item No. 8: Annual Presentation by Los Angeles Capital Management – Emerging Markets Equity Manager (May 11, 2016, Regular Retirement Board Meeting) INVESTMENT MANAGER SUMMARY MANAGEMENT Firm Name Los Angeles Capital Management Manager Tenure with Fund 3.5 Years Investment Strategy/Vehicle Emerging Markets Equity Contract Expiration N/A ASSETS Total Firm AUM (03/31/2016) $19.3 Billion Total Firm Assets in Strategy (03/31/2016) $5.0 Billion Total Assets Managed for WPERP (03/31/2016) RP - $230.9 Million HP - $38.4 Million PERFORMANCE As of 03/31/2016 Calendar 1 Year 3 Year Inception Y-T-D LA Capital Emerging Markets (gross) 7.20% -10.73% -3.49% -1.29% LA Capital Emerging Markets (est. net) 7.03% -11.31% -4.09% -1.92% MSCI Emerging Markets IMI ND 5.04% -11.66% -4.27% -2.44% Difference (net of fees) 1.99% 0.35% 0.18% 0.52% FEES Schedule 65 bps on all assets WATCH STATUS N/A 8 PRESENTATION FOR LOS ANGELES DEPARTMENT OF WATER & POWER EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT PLAN AND RETIREE HEALTH BENEFITS FUND LACM Emerging Markets Fund L.P. May 2016 LEGAL DISCLOSURES This presentation is for general information purposes only and does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security. Past performance is no guarantee of future results and diversification does not guarantee investment returns or eliminate the risk of loss. The strategies described herein have not been recommended by any Federal or State Securities Commission or regulatory authority. Furthermore, the foregoing authorities have not confirmed the accuracy or determined the adequacy of this presentation. -

Chimei Innolux Corp. Form CB Filed 2012-09-04

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM CB Notification form filed in connection with certain tender offers, business combinations and rights offerings, in which the subject company is a foreign private issuer of which less than 10% of its securities are held by U.S. persons Filing Date: 2012-09-04 SEC Accession No. 0001486620-12-000015 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) SUBJECT COMPANY Chimei Innolux Corp. Mailing Address Business Address NO. 160, KESYUE RD. NO. 160, KESYUE RD. CIK:1392387| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:D8 | Fiscal Year End: 1231 JHUNAN SCIENCE PARK JHUNAN SCIENCE PARK Type: CB | Act: 34 | File No.: 005-86971 | Film No.: 121069645 MIAOLI COUNTY 350 F5 MIAOLI COUNTY 350 F5 00000 00000 886-6-5051888 FILED BY Chimei Innolux Corp. Mailing Address Business Address NO. 160, KESYUE RD. NO. 160, KESYUE RD. CIK:1392387| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:D8 | Fiscal Year End: 1231 JHUNAN SCIENCE PARK JHUNAN SCIENCE PARK Type: CB MIAOLI COUNTY 350 F5 MIAOLI COUNTY 350 F5 00000 00000 886-6-5051888 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form CB TENDER OFFER/RIGHTS OFFERING NOTIFICATION FORM (AMENDMENT NO. ______) Please place an X in the box(es) to designate the appropriate rule provision(s) relied upon to file this Form: Securities Act Rule 801 (Rights Offering) x Securities Act Rule 802 (Exchange Offer) o Exchange Act Rule 13e-4(h)(8) (Issuer Tender Offer) o Exchange Act Rule 14d-1(c) (Third Party Tender o Offer) Exchange Act Rule 14e-2(d) (Subject Company o Response) Filed or submitted in paper if permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(8) o Note: Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(8) only permits the filing or submission of a Form CB in paper by a party that is not subject to the reporting requirements of Section 13 or 15(d) of the Exchange Act. -

Company Response Status and Score Company Response Status and Score

2017 Company response status and score Company response status and score Key to response status: AQ Answered questionnaire AQ (NP) Answered questionnaire but response not made public AQ (SA) Company is either a subsidiary or has merged during the reporting process; see Company in parenthesis for further information AQ (L) Answered questionnaire after submission deadline DP Declined to participate NR No response RV Responded voluntarily 1 Score levels: The levels build consecutively from Disclosure to Leadership. A threshold of 75% in a lower level has to be passed before a company is scored for the next level. For more information, please see our Introduction to Scoring. A Leadership A- B Management B- C Awareness C- D Disclosure D- F: Failure to provide sufficient information to CDP to be evaluated for this purpose 2 Company Response Status Ticker Country HQ CDP Band and Score Consumer Discretionary ABC-Mart, Inc. NR 2670 JP Japan Failure to disclose (F) AccorHotels DP AC FP France Failure to disclose (F) Adastria Co., Ltd. NR 2685 JP Japan Failure to disclose (F) adidas AG AQ ADS GR Germany Leadership (A-) Advance Auto Parts Inc NR AAP US USA Failure to disclose (F) Aisin Seiki Co., Ltd. AQ (NP) 7259 JP Japan Awareness (C) AKSA AKRILIK KIMYA SANAYII A.S. DP AKSA TI Turkey Failure to disclose (F) Anta Sports Products Ltd NR 2020 HK Hong Kong Failure to disclose (F) Aoyama Trading Co., Ltd. NR 8219 JP Japan Failure to disclose (F) 1 Companies that respond voluntarily to CDP are not scored unless they request this service. -

China Steel Corporation and Subsidiaries

China Steel Corporation and Subsidiaries Consolidated Financial Statements for the Three Months Ended March 31, 2021 and 2020 and Independent Auditors’ Review Report The engagement partners on the reviews resulting in this independent auditors’ review report are Jui-Hsuan Hsu and Cheng-Hung Kuo. Deloitte & Touche Taipei, Taiwan Republic of China May 7, 2021 Notice to Readers The accompanying consolidated financial statements are intended only to present the consolidated financial position, financial performance and cash flows in accordance with accounting principles and practices generally accepted in the Republic of China and not those of any other jurisdictions. The standards, procedures and practices to review such consolidated financial statements are those generally applied in the Republic of China. For the convenience of readers, the independent auditors’ review report and the accompanying consolidated financial statements have been translated into English from the original Chinese version prepared and used in the Republic of China. If there is any conflict between the English version and the original Chinese version or any difference in the interpretation of the two versions, the Chinese-language independent auditors’ review report and consolidated financial statements shall prevail. - 2 - CHINA STEEL CORPORATION AND SUBSIDIARIES CONSOLIDATED BALANCE SHEETS (In Thousands of New Taiwan Dollars) March 31, 2021 (Reviewed) December 31, 2020 (Audited) March 31, 2020 (Reviewed) ASSETS Amount % Amount % Amount % CURRENT ASSETS Cash and -

Fubon Financial Holding Co., Ltd. and Its Subsidiaries

FUBON FINANCIAL HOLDING CO., LTD. AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES Consolidated Interim Financial Statements June 30, 2014 and 2013 (With Independent Accountants' Report Thereon) FUBON FINANCIAL HOLDING CO., LTD. AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES Consolidated Balance Sheets June 30, 2014, and December 31 and June 30, 2013 (expressed in thousands of New Taiwan Dollars) June 30, 2014 December 31, 2013 June 30, 2013 June 30, 2014 December 31, 2013 June 30, 2013 Assets Amount % Amount % Amount % Liabilities and Stockholders' Equity Amount % Amount % Amount % Cash and cash equivalents (note 6 and 44) $ 168,447,311 3 194,224,779 4 139,581,491 3 Liabilities: Due from Central Bank and call loans to banks (note 7) 159,216,772 3 104,504,015 2 133,057,468 3 Due to Central Bank of China and other banks $ 110,658,221 2 91,718,827 2 74,685,907 2 Financial assets measured at fair value through profit or loss (note 8 and 44) 107,748,438 2 93,717,804 2 97,615,263 2 Financial liabilities measured at fair value through profit or loss (note 23) 47,980,175 1 43,000,297 1 39,319,830 1 Available-for-sale financial assets, net (note 9 and 44) 1,781,571,105 35 1,631,464,808 36 1,524,720,978 35 Hedging derivative financial liabilities (note 11) 1,853,027 - 1,872,070 - 2,080,308 - Hedging derivative financial assets (note 10) 524,606 - 517,817 - 630,617 - Securities sold under repurchase agreements (note 24) 91,898,020 2 48,188,694 1 42,248,367 1 Securities purchased under resell agreements (note 11) 70,055,362 1 72,391,296 2 74,050,430 2 Commercial paper payables, net (note 25) 5,823,522 -

Top 300 Organizations Granted U.S. Patents in 2020

Top 300 Organizations Granted U.S. Patents in 2020 38th Annual Listing This list of organizations that received the most U.S. utility patents is being published by IPO for the 38th consecutive year, in collaboration with Harrity Analytics. It is based on data obtained from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. For additional patent prosecution, technology, and law firm statistics related to the U.S. Patents issued in 2020, visit the Patent 300® website for an interactive dashboard. January 14, 2021 2020 Patent Owners Numerical Listing The total number of patents granted by the USPTO in 2020 was 352,469, down less than 1 percent from 2019. The data for an individual organization could be affected by mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, inconsistent treatment of subsidiaries in 2019 and 2020, and many other factors. New organizations on the list are provided on page 9. Change Change 2020 from 2020 from Rank Organization Patents 2019 Rank Organization Patents 2019 1 INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES 9435 0% 51 TCL CORPORATION 880 -30% 2 SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO., LTD. 8539 -1% 52 INFINEON TECHNOLOGIES AG 834 -12% 3 LG CORPORATION 5112 4% 53 HEWLETT PACKARD ENTERPRISE 831 1% 4 CANON K.K. 3689 -9% 54 GENERAL MOTORS COMPANY 802 -40% 5 INTEL CORPORATION 3284 -12% 55 WESTERN DIGITAL CORPORATION 788 6% 6 RAYTHEON TECHNOLOGIES 3213 1% 56 ORACLE CORPORATION 783 -11% 7 HUAWEI TECHNOLOGIES CO., LTD. 3178 9% 57 HALLIBURTON COMPANY 778 -24% 8 MICROSOFT CORPORATION 2972 -5% 58 NOKIA CORPORATION 757 -20% 9 TAIWAN SEMICONDUCTOR MFG. CO. 2892 22% 59 KIOXIA HOLDINGS CORPORATION 756 4% 10 SONY CORPORATION 2886 5% 60 CAPITAL ONE FINANCIAL CORP. -

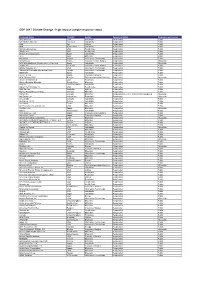

Grid Export Data

CDP 2017 Climate Change - high-impact sample response status Company Name Country Sector Response Status Response permission 3M Company USA Industrials Responded Public A.P. Moller - Maersk Denmark Industrials Responded Public A2A Italy Utilities Responded Public ABB Switzerland Industrials Responded Public Abbott Laboratories USA Health Care Responded Public AbbVie Inc USA Health Care Responded Public Abertis Infraestructuras Spain Industrials Responded Public ACC India Materials Responded Public Accenture Ireland Information Technology Responded Public AccorHotels France Consumer Discretionary Responded Not public ACS Actividades de Construccion y Servicios Spain Industrials Responded Not public adidas AG Germany Consumer Discretionary Responded Public Adobe Systems, Inc. USA Information Technology Responded Public Advanced Semiconductor Engineering Taiwan Information Technology Responded Public AENA SA Spain Industrials Responded Public Aeon Co., Ltd. Japan Consumer Staples Responded Public AFK Sistema JFSC Russia Telecommunication Services Responded Not public AFLAC Incorporated USA Financials Responded Public African Rainbow Minerals South Africa Materials Responded Public Aggreko United Kingdom Industrials Responded Public Agilent Technologies Inc. USA Health Care Responded Public AGL Energy Australia Utilities Responded Public Agnico-Eagle Mines Limited Canada Materials Responded Public Agrium Inc. Canada Materials Responded late, after analysis was completed Not public AIA Group Ltd. Hong Kong Financials Responded Not public Air Canada Canada Industrials Responded Public Air France - KLM France Industrials Responded Public Air Liquide France Materials Responded Public Air Products & Chemicals, Inc. USA Materials Responded Public Air Water Inc. Japan Materials Responded Not public Airbus Netherlands Industrials Responded Public Aisin Seiki Co., Ltd. Japan Consumer Discretionary Responded Public Ajinomoto Co.Inc. Japan Consumer Staples Responded Public AK Steel Holding Corporation USA Materials Responded Not public AKÇANSA ÇİMENTO SANAYİ VE TİCARET A.Ş. -

Table II: Intellectual Property-Based Import Investigations

Table II Intellectual Property-Based Import Investigations and Related Proceedings Conducted in Fiscal Year 2011 Date Fed. Reg. Final Orders Investigation No. and Title Complainant Notice1 Determination Issued Pub. No. 337-TA-4132 Certain Rare-Earth Magnets and Magnequench International, 07-09-10 Terminated 11-01-10 N/A Magnetic Materials and Articles Inc., Containing the Same Anderson, IN; (Advisory Opinion Proceeding) Sumitomo Special Metals Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan 337-TA-487 Certain Agricultural Vehicles and Deere & Company, 07-19-10 Pending Pending N/A Components Thereof Moline, IL (Remand) 337-TA-565 Certain Ink Cartridges and Epson Portland, Inc., 12-13-10 Pending Pending N/A Components Thereof Hillsboro, OR; (Advisory Opinion) Epson America Inc., Long Beach, CA; Seiko Epson Corporation, Nagano-Ken, Japan 337-TA-565 Certain Ink Cartridges and Epson Portland, Inc., 03-18-11 Pending Pending N/A Components Thereof Hillsboro, OR; (2 Consolidated Modification Epson America Inc., Proceedings) Long Beach, CA; Seiko Epson Corporation, Nagano-Ken, Japan 337-TA-567 Certain Foam Footwear Crocs, Inc., 05-27-10 General 07-15-11 N/A (Remand) Niwot, CO exclusion order and cease and desist orders 337-TA-568 Certain Products and Pharmaceutical Amgen, Inc., 06-22-09 Pending Pending N/A Compositions Containing Thousand Oaks, CA Recombinant Human Erythropoietin (Remand) 337-TA-587 Certain Connecting Devices for Norgren, Inc., 09-09-09 No violation 03-08-11 N/A Use with Modular Compressed Air Littleton, CO Conditioning Units, Including Filters, Regulators, and Lubricators (“FRL’s”) That are Part of Larger Pneumatic Systems and the FRL Units They Connect (Remand) 337-TA-6023 Certain GPS Devices and Products Global Locate, 12-07-10 Settlement 02-28-11 N/A Containing Same (Enforcement San Jose, CA agreement Proceeding) Table II Intellectual Property-Based Import Investigations and Related Proceedings Conducted in Fiscal Year 2011 Date Fed.