The BOOF to My Card Magic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Zavis Papers Finding

The William Zavis Papers prepared by Lenge Hong and Kat Masback fpliia 1 w\ 1JTJWHW nPf "'"Jf'' 'fl Conjuring Arts Research Center New York City : 2007 William Zavis finding aid.doc -1 Title: William Zavis Papers Span Dates: 1970-1993 Bulk Dates: 1973-1979 Accession No.: 2000.18 Creator: Kalush, William Extent: 2 linear feet. Language: English Repository: Conjuring Arts Research Center Finding Aid Prepared By: Lenge Hong and Katrina Masback Finding Aid Prepared Date: 7/12/2007 Provenance / Processing History: Related Material: Ask Alexander Status: Collection is not available via Ask Alexander. Copyright Status / Restrictions on Use: Please consult the librarian for further details. Preferred Citation: Researchers wishing to cite this collection should include the following information: container number, William Zavis Papers, Conjuring Arts Research Center, New York City. Scope and Content: Collection consists mainly of Zavis' correspondence with other magicians, societies, and magic supply houses, many based in the United Kingdom and Europe. Collection also includes instruction sheets for effects designed by Zavis, and assorted memorabilia. Search Terms: Zavis, William. Magicians. United States. 20th century. Magic tricks. Series List / Series Descriptions: The collection contains only one series. William Zavis finding aid.doc - 2 Container List box series folder description 1 1 William Zavis correspondence 1 James Alfredson (2); Anthony (1); Jack Avis (5); Roy Baker (5); Donald Bevan (30); Joe Berg (1); J. Birnman (1); George Blake (4); Bill Boley (1); John Braun (5); Martin Breese (3); Ken Brooke (7); TimBryson(l); Terry/Norma Burgess (1); Jeff Busby (8) 2 William Zavis correspondence 2 Carboni/Carbonita (2); Al Cohen (5); Leslie Cole (5); Alan Cracknell (1); Father Cyprian (1); L. -

Puzzling Magic Set

Puzzling Magic Set 9 2 1 12 8 7 3 4 5 6 Contents: 1. THE RUBIK’S TRIANGLE 6. CLASSIC SIZED TRICK CUBE 2. RUBIK’S TUBE 7. RUBIK’S MENTAL CUBE BOX AND SHELL 3. RUBIK’S CUBE BOX 8. RUBIK’S CUBE CLONING (RUBIK’S CUBE 4. 11 RUBIK’S ESP CARDS JAR, TRICK CUBE, AND 8 MINI CUBES) 5. 56 RUBIK’S MAGIC CARDS 9. 6 RUBIK’S HANKIES 10. INSTRUCTIONAL VIDEO DOWNLOAD INSTRUCTIONAL VIDEO DOWNLOAD Fantasmamagic.com/PuzzlingMagicSet Amazing, easy-to-perform tricks by Steve Vil. Layout by Jack Tawil, Suji Park, & Jessica Mercado. ©2017 Fantasma Toys Inc., www.FantasmaToys.com New York, NY 10001, USA . Made in China. ©1974 Rubik’s ® Used under licence Rubik’s Brand Ltd. All rights reserved. rubiks.com A Smiley company production | smiley.com • Keep for future reference. • Colours, style and decoration may vary. • Some tricks may require the use of ordinary household items. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. I TRICKS WITH THE RUBIK’S MENTAL 36. TIED AND UNTIED ...................................... 10 CUBE BOX AND SHELL 37. SUDSO ....................................................... 10 1. THE RUBIK’S MENTAL CUBE BOX AND SHELL 1 38. RESTORED ROPE ......................................... 10 2. THE RUBIK’S MENTAL CUBE PREDICTION .... 1 39. A COOL SHOW FINISH ............................... 10 3. THE VANISHING RUBIK’S CUBE ..................... 1 40. ANOTHER COOL SHOW FINISH! ................. 10 TRICKS WITH THE RUBIK’S CUBE BOX TRICKS WITH THE RUBIK’S CARDS 4. -

MAGIC-Artikel.Pdf

JANUARY 2012 U.S. $6 PIT H A R T L I N G THE MOST SUCCESSFUL GERMAN MAGICIAN IN HIS WEIGHT CLASS! BY RICHARD HATCH The Giersch Museum, on the south bank of the Main River in the heart of Frankfurt’s museum district, is a renovated three-story neo- classical villa built in 1910. Its primary mission, since opening as an art museum in September 2000, has been to showcase artists with a con- nection to the region but whose importance transcends the region’s boundaries. To carry out its mission, it generally stages two major exhibi- tions annually. The current exhibit focuses on the Italianate landscapes of Carl Morgenstern (1811–1893), one of the city’s most success- ful and renowned 19th-century painters. But recently the museum hosted the first of a planned series of performances showcasing another kind of artist: Frankfurt-based magi- cian Pit Hartling. The son of a hospital’s head doctor and the executive secretary to the CEO in charge of licensing of Disney products in Germany, Pit was born on January 25, 1976, in the village of Nieder-Erlenbach, now a section of Frankfurt. PIT Eight years later, Pit discovered an old magic set in his maternal great-aunt Emma’s basement. “There was no one particularly interested in magic in the family,” Pit recalls. “Why she had H A R T L I N G that old magic set is somewhat of a mystery.” The wooden props made fascinating playthings. This discovery was the start of an increasingly obsessive interest in conjuring. -

David Copperfield PAGE 36

JUNE 2012 DAVID COPPERFIELD PAGE 36 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan Proofreader & Copy Editor Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Publisher Society of American Magicians, 6838 N. Alpine Dr. Parker, CO 80134 Copyright © 2012 Subscription is through membership in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues should be addressed to: Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator P.O. Box 505, Parker, CO 80134 [email protected] Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 Fax: 303-362-0424 Send assembly reports to: [email protected] For advertising information, reservations, and placement contact: Mona S. Morrison, M-U-M Advertising Manager 645 Darien Court, Hoffman Estates, IL 60169 Email: [email protected] Telephone/fax: (847) 519-9201 Editorial contributions and correspondence concerning all content and advertising should be addressed to the editor: Michael Close - Email: [email protected] Phone: 317-456-7234 Fax: 866-591-7392 Submissions for the magazine will only be accepted by email or fax. VISIT THE S.A.M. WEB SITE www.magicsam.com To access “Members Only” pages: Enter your Name and Membership number exactly as it appears on your membership card. 4 M-U-M Magazine - JUNE 2012 M-U-M JUNE 2012 MAGAZINE Volume 102 • Number 1 S.A.M. NEWS 6 From the Editor’s Desk Photo by Herb Ritts 8 From the President’s Desk 11 M-U-M Assembly News 24 New Members 25 -

The Underground Sessions Page 36

MAY 2013 TONY CHANG DAN WHITE DAN HAUSS ERIC JONES BEN TRAIN THE UNDERGROUND SESSIONS PAGE 36 CHRIS MAYHEW MAY 2013 - M-U-M Magazine 3 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan Proofreader & Copy Editor Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Publisher Society of American Magicians, 6838 N. Alpine Dr. Parker, CO 80134 Copyright © 2012 Subscription is through membership in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues should be addressed to: Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator P.O. Box 505, Parker, CO 80134 [email protected] Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 Fax: 303-362-0424 Send assembly reports to: [email protected] For advertising information, reservations, and placement contact: Mona S. Morrison, M-U-M Advertising Manager 645 Darien Court, Hoffman Estates, IL 60169 Email: [email protected] Telephone/fax: (847) 519-9201 Editorial contributions and correspondence concerning all content and advertising should be addressed to the editor: Michael Close - Email: [email protected] Phone: 317-456-7234 Submissions for the magazine will only be accepted by email or fax. VISIT THE S.A.M. WEB SITE www.magicsam.com To access “Members Only” pages: Enter your Name and Membership number exactly as it appears on your membership card. 4 M-U-M Magazine - MAY 2013 M-U-M MAY 2013 MAGAZINE Volume 102 • Number 12 26 28 36 PAGE STORY 27 COVER S.A.M. NEWS 6 From -

Double Magazine 2.Pdf

Introduction Hi all, Welcome to the 2nd Issue of Magic E – Magazine – The Double Magazine! In this issue you will find: An Interview with legend; Peter Duffie! A trick from me; Kyle MacNeill! A trick from David Devlin! A review of Blackpool Magic Convention 2011! A review of High Spots by Caleb Wiles! A Competition! Enjoy! Its jam – packed with loads of great magical goodies, including tricks, reviews, interviews, competitions, and more! Please send any feedback either on the thread on the Cafe‟, or send it to Kyle@MacNeill- family.freeserve.co.uk Please send any letters, competition entries or tricks to the same address! Thanks, Kyle MacNeill, February 2011 Interview with Peter Duffie In this issue, we catch up with magic Spirit Level; Peter Duffie‟s legend Peter Duffie. Enjoy! marketed trick. 1. Now we all have some sort of moment of astonishment, or some sort of event or happening, which gets us magicians into the art of magic. Roy Walton. Roy is one of the most intelligent people I know. When and why did you start? When I first met Alex Elmsley in the early 1970's - I immediately realised why he and Roy were close friends. They are/were both great thinkers without an ego. Roy enthuses at I first became fascinated by magic at the other people's achievements and his generosity towards age of eight after my uncle showed me others is remarkable. some magic tricks using cards, coins, matches and chalk. But it was the cards Other people who I met and had a profound influence on me, that held my deepest interest. -

My Magic Ebook Collection

Magician books Aaron Fisher The Paper Engine FISM 2003 The Graduate Genii article 2009 Aaron Shields Dribble Block Pass Al Koran Legacy Professonal Presentations Alex Elmsley Collected works vol 1-2 Allan Ackerman Las Vegas Kardma 2004 lecture notes classic handlings here's my card the cardjuror 2012 notes Andi Gladwin The Cheetah's Handbook1-2 Andrew Wimhurst Down Under Deal Andy Nyman Bulletproof Annemann Practical Mental Magic The Jinx the life and times of a legend Anthony black Acaan Emote OOBE Resurrection dreams The sight of madness Antinomy 2005, 2006 Arthur Buckley Card control Improved and original card problems Asi Wind Chapter One Arturo de Ascano The magic of Ascanio vol 1-3 Atlas Brooking The prodigal the crusade Banachek Pyschological Subleties 1-3 Psychological Thought Reading Benjamin Earl Past midnight Bonus Booklet Dr Strangehand How to fool a Physicist Gambit 1&2 Bert Allerton The Close Up Magician Bill Cushman The Dr's Billet Tear Bill Dekel direct Mindcrafts psionics, visions Air Writer Digit Bill Goodwin Penumbra 1-11 lecture 1988 notes from the batcave the ancient empty street (1997) Evolution(2011) At the expense of grey matter Mini Lecture SAM 1994 Picking the carcas clean Theatricks Bill Montana psychic motherfucker Bill Simon Effective Card Magic bobo Modern Coin Magic Boris Wild ACAAB Brandon Queen Phatom Bruce Cervon Lecture notes 1995 card secrets Hard boiled mysteries Ultra Cervon Bryn reynolds the logar scrolls bullfrog issue 0-2 Caleb Wiles High Spots Cameron Francis Aberrations Convergence Everywhere -

Free Issue 68.Pdf

Welcome to your FREE evaluation copy of Magicseen Magicseen is published every 2 months and is available via a 1 or 2 year subscription, either in printed copy format delivered by mail, or as a download. You can also opt to take out an open ended printed copy Pay As You Go subscription, in which you provide payment card details and we charge you for a single issue each time a new one appears. If you sign up for one of our subscription options above here are the EXTRA benefits that you will enjoy. 1 or 2 year printed copy or PAYG subscribers receive 20% off all Magicseen books and E-Books plus they can opt to receive a free download copy of each issue in advance of the printed copy arriving. Download subscribers receive 20% off all Magicseen books and E-Books plus every time a new issue is released, they can select to receive any two further download back issues for FREE For more info and to subscribe go to www.magicseen.co.uk Magicseen, Anne's Park, Cowley, Exeter EX5 5EN, England Tel: +44 (0)1392 490565 Magicseen is sponsored by Card Shark (www.card-shark.de) PHONEBOX > MASTERCLASS > LETTERS > PRODUCT REVIEWS MAGAZINE IssueMAGICseen No. 68 RRP £5.50 Vol 12. No.2 May 2016 Paul Daniels A look AT his brilliant career Xavier Tapias Rubbish & Robots! Vox Magique Plus: It Takes TwO... > CLOWNING > DEALERS’ BOOTH > HOW TO BOOK MORE SHOWS > RAFAEL RULES THE WORLD JOSHUA JUST JAY MAGIC MAGICSEEN > YOU’LL LIKE IT... BUT NOT A LOT! NEVER TOUCH OR SEE THE CARD...YET KNOW EXACTLY WHAT WAS DRAWN! NO CARBON COPIES • NO PEEKING • EXAMINABLE • SELF CONTAINED AVAILABLE AT: EDITOR’S LETTER ummer is hopefully on the way and we have a bright and Ssunny issue to get you in the mood (was that cheesy enough for you?). -

Prices Correct Till May 19Th

Online Name $US category $Sing Greater Magic Volume 18 - Charlie Miller - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Greater Magic Volume 42 - Dick Ryan - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Greater Magic Volume 23 - Bobo - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Greater Magic Volume 20 - Impromptu Magic Vol.1 - DVD $ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 Torn And Restored Newspaper by Joel Bauer - DVD$ 30.00 Videos$ 48.00 City Of Angels by Peter Eggink - Trick $ 25.00 Tricks$ 40.00 Silk Poke Vanisher by Goshman - Trick $ 4.50 Tricks$ 7.20 Float FX by Trickmaster - Trick $ 30.00 Tricks$ 48.00 Stealth Assassin Wallet (with DVD) by Peter Nardi and Marc Spelmann - Trick$ 180.00 Tricks$ 288.00 Moveo by James T. Cheung - Trick $ 30.00 Tricks$ 48.00 Coin Asrah by Sorcery Manufacturing - Trick $ 30.00 Tricks$ 48.00 All Access by Michael Lair - DVD $ 20.00 Videos$ 32.00 Missing Link by Paul Curry and Mamma Mia Magic - Trick$ 15.00 Tricks$ 24.00 Sensational Silk Magic And Simply Beautiful Silk Magic by Duane Laflin - DVD$ 25.00 Videos$ 40.00 Magician by Sam Schwartz and Mamma Mia Magic - Trick$ 12.00 Tricks$ 19.20 Mind Candy (Quietus Of Creativity Volume 2) by Dean Montalbano - Book$ 55.00 Books$ 88.00 Ketchup Side Down by David Allen - Trick $ 45.00 Tricks$ 72.00 Brain Drain by RSVP Magic - Trick $ 45.00 Tricks$ 72.00 Illustrated History Of Magic by Milbourne and Maurine Christopher - Book$ 25.00 Books$ 40.00 Best Of RSVPMagic by RSVP Magic - DVD $ 45.00 Videos$ 72.00 Paper Balls And Rings by Tony Clark - DVD $ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Break The Habit by Rodger Lovins - Trick $ 25.00 Tricks$ 40.00 Can-Tastic by Sam Lane - Trick $ 55.00 Tricks$ 88.00 Calling Card by Rodger Lovins - Trick $ 25.00 Tricks$ 40.00 More Elegant Card Magic by Rafael Benatar - DVD$ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Elegant Card Magic by Rafael Benatar - DVD $ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Elegant Cups And Balls by Rafael Benatar - DVD$ 35.00 Videos$ 56.00 Legless by Derek Rutt - Trick $ 150.00 Tricks$ 240.00 Spectrum by R. -

Avisit to Main Street Magic Page 36

OCTOBER 2015 Volume 105 Number 4 AVisit to Main Street Magic Page 36 MAGIC - UNITY - MIGHT Editor Michael Close Editor Emeritus David Goodsell Associate Editor W.S. Duncan 40.00 Proofreader & Copy Editor $3 Lindsay Smith Art Director Lisa Close Online Edition Coordinator Bruce Kalver Publisher Society of American Magicians, 4927 S. Oak Ct., Littleton, CO 80127 SPECIAL OFFER! Copyright © 2015 $340 or 6 monthly payments of $57 Subscription is through membership Shipped upon first payment! in the Society and annual dues of $65, of which $40 is for 12 issues of M-U-M. All inquiries concerning membership, change of address, and missing or replacement issues EVERYTHING YOU NEED should be addressed to: TO SOUND LIKE A PRO You could open the box at your show! Manon Rodriguez, National Administrator 4927 S. Oak Ct. Littleton, CO 80127 [email protected] For audiences of up to 400 people. Skype: manonadmin Phone: 303-362-0575 All-inclusive! Handheld, Headsets, lapel Fax: 303-362-0424 mics, speaker, receiver (built in), highest quality battery, inputs, outputs.. www.mum-magazine.com SPEAKER STAND, HARD CASE, CORDS. To file an assembly report go to: For advertising information, All for just $340 reservations, and placement contact: Most trusted system on the market. Cinde Sanders, M-U-M Advertising Manager Email: [email protected] Telephone: 214-902-9200 Editorial contributions and correspondence Package Deal includes: concerning all content and advertising Amazing Amp speaker, removable re- should be addressed to the editor: chargeable 12V battery, power cord, (2) Michael Close - Email: [email protected] headset mics, (2) lapel mics, carrying Phone: 317-456-7234 Submissions for the magazine will only be bag, (3) 9V batteries, (2) belt pack accepted by email or fax. -

P.T. Selbit Dr. A.M. Wilson J.B. Bobo U.F. Grant

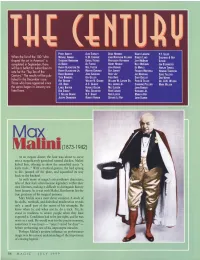

Percy Abbott Alex Elmsley Doug Henning Harry Lorayne P.T. Selbit When the list of the 100 "who Michael Ammar S.W. Erdnase John Northern Hilliard Robert Lund Siegfried & Roy shaped the art in America" is Theodore Annemann Dariel Fitzkee Professor Hoffmann Jeff McBride Slydini completed in September, there Al Baker Al Flosso Harry Houdini Billy McComb Jim Steinmeyer will be a ballot for subscribers to Harry Blackstone Sr. Neil Foster Jean Hugaro Ed Marlo Harlan Tarbell arry lackstone r artin ardner uy arrett vote for the "Top Ten of the H B J . M G G J Frances Marshall Howard Thurston David Bamberg John Gaughan Ricky Jay Jay Marshall ddie ullock Century." The results will be pub E T Theo Bamberg Uri Geller Fred Kaps Gary Ouellet lished in the December issue. Don Wayne Roy Benson Walter B. Gibson William W. Larsen Sr. Penn & Teller Dr. A.M. Wilson Those who have appeared since J.B. Bobo A.C. Gilbert Bill Larsen Jr. Channing Pollock Mark Wilson the series began in January are Lance Burton Horace Goldin Milt Larsen John Ramsay listed here. Ben Chavez Will Goldston Rene Lavand Richiardi Jr. T. Nelson Downs U.F. Grant Nate Leipzig Marvyn Roy Joseph Dunninger Robert Harbin Servais Le Roy John Scarne At an elegant dinner, the host was about to carve into a -magnificently garnished roasted chicken. Malini halted him, offering to show the assembled party “a leetle trick...” With a mystical gesture, the bird sprang to life, jumped off the plate, and squawked its way back to the kitchen! As with many of magic’s extraordinary characters, tales of their feats often became legendary within their own lifetimes, making it difficult to distinguish history from fantasy. -

Dai Vernon & Bruce Cervon

Public Auction Sale #005 The Collections of Dai Vernon & Bruce Cervon and Fine Vintage Magic, Including Apparatus, Posters, Ephemera and Rare Books Saturday, January 30, 2010 10:00 AM Exhibition January 28 &29, 10 - 5 For Inquiries, call 773-472-1442 Or email [email protected] The printed edition of this catalog is available from www.potterauctions.com Place bids and browse color photos of each lot (beginning Dec. 22) at www.liveauctioneers.com Auction & exhibition to be held at our new Chicago gallery (address below) 3726 N. Ravenswood Ave. -Suite 116- Chicago, Illinois 60617 Introduction ollywood became the center of the magic world in 1963. That year, Dai Vernon, known to Hmagicians world wide as “The Professor,” moved to California. On arrival, Vernon took up residence at the Magic Castle, where he would remain a fixture for the next 25 years — and become an icon. From the Castle flowed Vernon’s dictum of natural magic; he avowed deep study of the art as a route to perfection. These and other mantras he would impart both through the written word and in person, to countless associates, fans and students. In 1964, a Midwestern sleight-of-hand artist, Bruce Cervon, also moved west. Southern California, he’d been assuredd, was the nexus of all things magical. The Magic Castle was the place to perform close-up magic. And Vernon was there. Almost immediately upon their initial meeting, Cervon and Vernon developed a strong, important friendship and student/teacher relationship. From their sessions came weighty ideas, concepts and published works: most prominently, Cervon’s Castle Notebooks and The Vernon Chronicles.