History of Woman Suffrage and Voting Rights Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eliza Calvert Hall: Kentucky Author and Suffragist

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 2007 Eliza Calvert Hall: Kentucky Author and Suffragist Lynn E. Niedermeier Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Niedermeier, Lynn E., "Eliza Calvert Hall: Kentucky Author and Suffragist" (2007). Literature in English, North America. 54. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/54 Eliza Calvert Hall Eliza Calvert Hall Kentucky Author and Suffragist LYNN E. NIEDERMEIER THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Frontispiece: Eliza Calvert Hall, after the publication of A Book of Hand-Woven Coverlets. The Colonial Coverlet Guild of America adopted the work as its official book. (Courtesy DuPage County Historical Museum, Wheaton, 111.) Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2007 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Niedermeier, Lynn E., 1956- Eliza Calvert Hall : Kentucky author and suffragist / Lynn E. -

Some Kind of Lawyer”: Two Journeys from Classroom to Courtroom and Beyond

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications 1996 “Some Kind of Lawyer”: Two Journeys from Classroom to Courtroom and Beyond Terry Birdwhistell University of Kentucky, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Legal Education Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Terry Birdwhistell, “Some Kind of Lawyer”: Two Journeys from Classroom to Courtroom and Beyond, 84 Ky. L.J. 1125 (1996). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Some Kind of Lawyer”: Two Journeys from Classroom to Courtroom and Beyond Notes/Citation Information Kentucky Law Journal, Vol. 84, No. 4 (1995-1996), pp. 1125-1152 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/132 "Some Kind of Lawyer": Two Journeys from Classroom to Courtroom and Beyond EDITED BY TERRY BIRDWHISTELL* F ollowing graduation from the University of Kentucky College of Law in 1952, Norma Boster Adams worked briefly as a legal secretary and eventually began practicing law in Somerset, Kentucky. One day a man came into her office and announced, "I'm looking for a lawyer, and they tell me over at the bank that you're some kind of 1' lawyer.' Almost thirty years later, Annette McGee Cunningham began work for the Legal Services office in Lexington following her graduation from the University of Kentucky College of Law in 1980. -

Student Research- Women in Political Life in KY in 2019, We Provided Selected Museum Student Workers a List of Twenty Women

Student Research- Women in Political Life in KY In 2019, we provided selected Museum student workers a list of twenty women and asked them to do initial research, and to identify items in the Rather-Westerman Collection related to women in Kentucky political life. Page Mary Barr Clay 2 Laura Clay 4 Lida (Calvert) Obenchain 7 Mary Elliott Flanery 9 Madeline McDowell Breckinridge 11 Pearl Carter Pace 13 Thelma Stovall 15 Amelia Moore Tucker 18 Georgia Davis Powers 20 Frances Jones Mills 22 Martha Layne Collins 24 Patsy Sloan 27 Crit Luallen 30 Anne Northup 33 Sandy Jones 36 Elaine Walker 38 Jenean Hampton 40 Alison Lundergan Grimes 42 Allison Ball 45 1 Political Bandwagon: Biographies of Kentucky Women Mary Barr Clay b. October 13, 1839 d. October 12, 1924 Birthplace: Lexington, Kentucky (Fayette County) Positions held/party affiliation • Vice President of the American Woman Suffrage Association • Vice President of the National Woman Suffrage Association • President of the American Woman Suffrage Association; 1883-? Photo Source: Biography https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Barr_Clay Mary Barr Clay was born on October 13th, 1839 to Kentucky abolitionist Cassius Marcellus Clay and Mary Jane Warfield Clay in Lexington, Kentucky. Mary Barr Clay married John Francis “Frank” Herrick of Cleveland, Ohio in 1839. They lived in Cleveland and had three sons. In 1872, Mary Barr Clay divorced Herrick, moved back to Kentucky, and took back her name – changing the names of her two youngest children to Clay as well. In 1878, Clay’s mother and father also divorced, after a tenuous marriage that included affairs and an illegitimate son on her father’s part. -

The Kentucky High School Athlete, March 1966 Kentucky High School Athletic Association

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass The Athlete Kentucky High School Athletic Association 3-1-1966 The Kentucky High School Athlete, March 1966 Kentucky High School Athletic Association Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete Recommended Citation Kentucky High School Athletic Association, "The Kentucky High School Athlete, March 1966" (1966). The Athlete. Book 118. http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete/118 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Kentucky High School Athletic Association at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Athlete by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r HighSc/ioo/Athlete THE KENTUCKY SCHOOL FOR THE BLIND 1966 CHAMPIONSHIP WRESTLING TEAM (Left ro Right) Front Row: Earl Jones, Jimmy Whitehouse, Dan Dickerson, Larry Crowe, Virgil Ritchie, Joe Gary Flint, Edward iMyers, Joe Triplette. Second Row: Ass't Coach Will D. Evans, Richard Lewis, Grady Curlin, Larry Cook, James Earl Hardin, Earl Wayne Moore, Larry Kerr, Coach W. Edward Murray, Jr. Official Organ of (lie KENTUCKY HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION March, 1986 : — Modern Ides of March Tilt ayni lij^hts yleam iikt a beacon beam And a million motors hum In a good will flight on a Fridaj night For basketball biJckons '•( ome!" A r^harp-shooting mite is king tonight The Madness of March is running. The winged feet fly. the ball sails high And field goal hunters are gunning. Tin toliu - clasl. u ->ih- un llci^li And race od a .•shimmering fiooi R('l>tes^i(ins die. and paiti-sans \\i' III a s>nal a( rlaimin!.' roai Oil Championship Trail toward a hoi} grail All fans are birds of a feather. -

Empowering and Inspiring Kentucky Women to Public Service O PENING DOORS of OPPORTUNITY

Empowering and Inspiring Kentucky Women to Public Service O PENING DOORS OF OPPORTUNITY 1 O PENING DOORS OF OPPORTUNITY Table of Contents Spotlight on Crit Luallen, Kentucky State Auditor 3-4 State Representatives 29 Court of Appeals 29 Government Service 5-6 Circuit Court 29-30 Political Involvement Statistics 5 District Court 30-31 Voting Statistics 6 Circuit Clerks 31-33 Commonwealth Attorneys 33 Spotlight on Anne Northup, County Attorneys 33 United States Representative 7-8 County Clerks 33-35 Community Service 9-11 County Commissioners and Magistrates 35-36 Guidelines to Getting Involved 9 County Coroners 36 Overview of Leadership Kentucky 10 County Jailers 36 Starting a Business 11 County Judge Executives 36 County PVAs 36-37 Spotlight on Martha Layne Collins, County Sheriffs 37 Governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky 12-13 County Surveyors 37 Kentucky Women in the Armed Forces 14-19 School Board Members 37-47 Mayors 47-49 Spotlight on Julie Denton, Councilmembers and Commissioners 49-60 Kentucky State Senator 20-21 Organizations 22-28 Nonelected Positions Statewide Cabinet Secretaries 60 Directory of Female Officials 29-60 Gubernatorial Appointees to Boards and Commissions since 12/03 60-68 Elected Positions College Presidents 68 Congresswoman 29 Leadership Kentucky 68-75 State Constitutional Officers 29 State Senators 29 Acknowledgments We want to recognize the contributions of the many Many thanks also go to former Secretary of State Bob who made this project possible. First, we would be Babbage and his staff for providing the initial iteration remiss if we did not mention the outstanding coopera- for this report. -

2003-Fall.Pdf

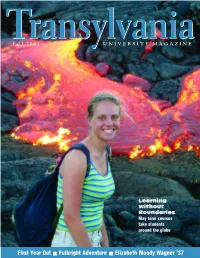

TTFall 2003ransylvaniaransylvaniaUNIVERSITY MAGAZINE Learning without Boundaries May term courses take students around the globe First Year Out ■ Fulbright Adventure ■ Elizabeth Moody Wagner ’37 SummeratTransySummeratTransy LearnLearn PlayPlay RelaxRelax CreateCreate CompeteCompete CelebrateCelebrate TeachTeach ExcelExcel TransylvaniaUNIVERSITY MAGAZINE FALL/2003 Features 2 Learning without Boundaries From Hawaii to Greece, destinations are varied for students taking May term travel courses 8 First Year Out Members of the class of 2002 learn some of life’s 2 many lessons during their first year after Transy 11 A Fulbright Adventure Fulbright award sends biology professor Peter Sherman to Oman for new insights into teaching and research 12 A Flying Start Elizabeth Moody Wagner ’37 helped pioneer women in aviation as a flight instructor during World War II 11 14 Ronald F. Whitson: 1944-2003 Long-time coach, teacher, and administrator was integral part of Transylvania basketball heritage Departments 12 15 Around Campus l 20 Applause Alumni News and Notes 23 Class Notes 25 Alumni Profile: Donald Manasse ‘71 26 Art Exhibit: Louise Calvin 29 Marriages, births, obituaries on the cover Director of Public Relations: Sarah A. Emmons ■ Director of Publications: Junior Stephanie Edelen Martha S. Baker ■ Publications Writer/Editor: William A. Bowden ■ Publica- poses in front of a lava flow on Kilauea in Hawaii tions Assistant: Katherine Yeakel ■ Publications Designer: Barbara Grinnell Volcanoes National Park during the May term course Transylvania is published three times a year. Volume 21, No.1, Fall 2003. Tropical Ecology. For more Produced by the Office of Publications, Transylvania University, Lexington, on May term travel courses, see story on KY 40508-1797. -

HISTORY SAYRE SCHOOL Www^W^S^Ww^^^^^^^^^Wm

HISTORY OF SAYRE SCHOOL By J. WINSTON COLEMAN, JR. www^w^s^ww^^^^^^^^^wm A Centennial History of Sayre School Sayre School has long been one of the outstanding in stitutions for the education of women in Kentucky, and owes its existence to the munificence of David A. Sayre, of Lexington, after whom it is named. Mr. Sayre had come to this city from New Jersey in 1811, when quite a young man as an apprenticed silversmith. From absolute pov erty he had, by thrift and economy, become a banker as early as 1829, and subsequently amassed a large fortune, a considerable portion of which was devoted to the use of public institutions connected with the Presbyterian Church, of which he was a member. He became interested in edu cational matters and determined to establish a first-class school for girls, whose benefits should be as widely dis tributed as possible. Mr. Sayre purchased a large lot and two-story brick building from George W. Sutton at the northwest corner of Mill and Church streets, which he dedicated to the cause of female education; and here on November 1st, 1854, the School was organized under the care of the Reverend Henry V. D. Nevius, pastor of the Walnut Hill Church and Prin cipal of the Walnut Hill Seminary, in Fayette County, six miles east of Lexington on the Richmond Road. The newly-organized School was called Transylvania Female Seminary, and students were received shortly after it opened its doors; the Reverend Nevius bringing with him some of his former pupils from the country school. -

How Women Won the Vote

Equality Day is August 26 March is Women's History Month National Women's History Project How Women Won the Vote 1920 Celebrating the Centennial of Women's Suffrage 2020 Volume Two A Call to Action Now is the Time to Plan for 2020 Honor the Successful Drive for Votes for Women in Your State ENS OF THOUSANDS of organizations and individuals are finalizing plans for extensive celebrations for 2020 in honor Tof the 100 th anniversary U.S. women winning the right to vote. Throughout the country, students, activists, civic groups, artists, government agen- cies, individuals and countless others are prepar- ing to recognize women's great political victory as never before. Their efforts include museum shows, publica- tions, theater experiences, films, songs, dramatic readings, videos, books, exhibitions, fairs, pa- rades, re-enactments, musicals and much more. The National Women's History Project is one of the leaders in celebrating America's women's suffrage history and we are encouraging every- one to recognize the remarkable, historic success of suffragists one hundred years ago. Here we pay tribute to these women and to the great cause to which they were dedicated. These women overcame unbelievable odds to win their own civil rights, with the key support of male voters and lawmakers. This is a celebration for both women and men. Join us wherever you are. There will be many special exhibits and obser- vances in Washington D.C. and throughout the WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE nation, some starting in 2019. Keep your eyes open; new things are starting up every day. -

Clay Bennett

H-Kentucky Sarah "Sallie" Clay Bennett Archive Item published by KyWoman Suffrage on Friday, February 15, 2019 Project Name: Kentucky Woman Suffrage Name of Historic Site: Richmond Cemetery Event(s)/Use associated with woman/group/site: Burial place of Sarah "Sallie" Clay Bennett County: Madison Town/City: Richmond Zip Code: 40475 Street Address: 606 E Main St Associated Organization: Richmond Cemetery Years of Importance: 1880-1894 1894-1912 Geographic Location: Citation: KyWoman Suffrage. Sarah "Sallie" Clay Bennett. H-Kentucky. 02-15-2019. https://networks.h-net.org/sarah-sallie-clay-bennett Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. 1 H-Kentucky Your Affiliation: Kentucky Woman Suffrage Project Additional Comments: Sallie Clay Bennett (1841-1935) was the daughter of Mary Jane Warfield Clay and sister to Laura Clay and Mary Barr Clay, each members of the suffrage movement. Bennett herself was a prominent member of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association and President of the Madison County Equal Rights Association. She was married to James Bennett of Richmond and together they had five children. As early as 1882 on behalf of the Kentucky Woman Suffrage Association (precursor to KERA) and Madison County ERA, she lobbied together with her sister Mary Barr Clay the judiciary committee of the state Senate - seeking municipal and presidential suffrage, property rights for married women, and guardianship of children. She spoke before the U.S. Senate Committee on Woman Suffrage -

Sayre School Upper School Student Handbook 2012-2013 240 North

Sayre School Upper School Student Handbook 2012-2013 240 North Limestone Street Lexington, Kentucky 40507-1121 Telephone: (859) 389-7390 Stephen M. Manella, Head of School Timothy J. O'Rourke, Upper School Director Randy Mills, College Counselor Marti Quintero, Dean of Students Robin S. Haden, Upper School Administrative Assistant Community Matters: Wisdom, Integrity, Respect, and Compassion As students of Sayre School, we expect to treat and be treated fairly, equally, with consideration and respect. We do not tolerate discrimination, stereotyping or degrading actions or language towards any person or group. Student Diversity Council May 2010 1 INTRODUCTION David Austin Sayre, a man of humble origin who received most of his education by hard work and experience rather than by formal education, founded Sayre School. David Sayre was born on March 12, 1793, near Madison, New Jersey, and was apprenticed as a youth to a silversmith. In 1811, Sayre left his home traveling west to Lexington in pursuit of his trade. Within a short time, he became his own master and eventually expanded into banking where he accumulated a large fortune. During the course of his life, and with the counsel of his wife, Abby, he donated a large portion of his wealth to the Presbyterian Church and to numerous local charities. In 1854, convinced of the need for female education, he founded a school for girls located on the corner of Mill and Church Streets. The school proved to be highly successful and within a year outgrew its original location. As a result, in 1856, Mr. Sayre purchased a five-acre tract on Limestone Street (Johnson's Grove) and the school moved to its present location. -

Women in Kentucky

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Women's History History 1979 Women in Kentucky Helen D. Irvin Transylvania University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Irvin, Helen D., "Women in Kentucky" (1979). Women's History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_womens_history/3 The Kentucky Bicentennial Bookshelf Sponsored by KENTUCKY HISTORICAL EVENTS CELEBRATION COMMISSION KENTUCKY FEDERATION OF WOMEN'S CLUBS and Contributing Sponsors AMERICAN FEDERAL SAVINGS & LOAN ASSOCIATION ARMCO STEEL CORPORATION, ASHLAND WORKS A. ARNOLD & SON TRANSFER & STORAGE CO., INC. I ASHLAND OIL, INC. BAILEY MINING COMPANY, BYPRO, KENTUCKY I BEGLEY DRUG COMPANY J. WINSTON COLEMAN, JR. I CONVENIENT INDUSTRIES OF AMERICA, INC. IN MEMORY OF MR. AND MRS. J. SHERMAN COOPER BY THEIR CHILDREN CORNING GLASS WORKS FOUNDATION I MRS. CLORA CORRELL . THE COURIER-JOURNAL AND THE LOUISVILLE TIMES COVINGTON TRUST & BANKING COMPANY MR. AND MRS. GEORGE P. CROUNSE I GEORGE E. EVANS, JR. FARMERS BANK & CAPITAL TRUST COMPANY I FISHER-PRICE TOYS, MURRAY MARY PAULINE FOX, M.D., IN HONOR OF CHLOE GIFFORD MARY A. HALL, M.D., IN HONOR OF PAT LEE, JANICE HALL & AND MARY ANN FAULKNER OSCAR HORNSBY INC. I OFFICE PRODUCTS DIVISION IBM CORPORATION JERRY'S RESTAURANTS I ROBERT B. JEWELL LEE S. JONES I KENTUCKIANA GIRL SCOUT COUNCIL KENTUCKY BANKERS ASSOCIATION I KENTUCKY COAL ASSOCIATION, INC. -

Kentucky Woman Suffrage Activity Book

VOTES FOR KENTUCKY WOMEN: HOW KENTUCKY JOINED THE NATION IN THE FIGHT FOR WOMEN’S S UFFRAGE A Student Activity Book Celebrating the Centennial of the 19th Amendment, 1920-2020 Cover photo: Kentucky Governor Edwin P. Morrow signing the Kentucky legislature's ratification of the 19th Amendment, January 6, 1920. Library of Congress, Lot 5543. www.loc.gov/item/97510716 Governor Edwin P. Morrow (seated). The woman standing behind Governor Morrow - with her hands resting on the back of his chair - is his wife, Katherine Hale Waddle Morrow (former president of Pulaski County Equal Rights Association). Beside First Lady Morrow, behind the Governor, is Madeline McDowell Breckinridge (of Lexington, President of Kentucky Equal Rights Association). Next to Breckinridge is Caroline Apperson Leech (of Louisville, 3rd Vice President of KERA). To the right of Leach, Josephine Fowler Post (of Paducah, Kentucky's state member to the NAWSA National Executive Council). Eleanor Hume Offutt (of Frankfort, KERA Member Campaign Committee chair) is the younger woman in the front row with her head just above the Governor's head. To Offutt's right is Rebecca R. Judah (of Louisville, KERA Treasurer) and Margaret Weissinger Castleman (of Louisville, 2nd Vice President of KERA). In the center with her left hand on the desk: Jessie Riddell Firth (of Covington, KERA Recording Secretary). Behind Firth's right shoulder, Martina Grubbs Riker (president of the Kentucky Federation of Women's Clubs). In front of the desk, near the telephones (2nd in from the left) is Alice Barbee Castleman (of Louisville, KERA Advisory Board) then Elise Bennett Smith (of Louisville, KERA Advisory Board).