The Journal of North American Herpetology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

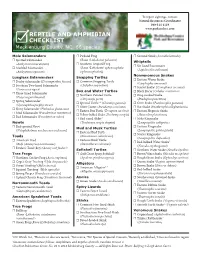

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

211356675.Pdf

306.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE STORERIA DEKA YI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. and western Honduras. There apparently is a hiatus along the Suwannee River Valley in northern Florida, and also a discontin• CHRISTMAN,STEVENP. 1982. Storeria dekayi uous distribution in Central America . • FOSSILRECORD. Auffenberg (1963) and Gut and Ray (1963) Storeria dekayi (Holbrook) recorded Storeria cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean (pleisto• Brown snake cene) of Florida, and Holman (1962) listed S. cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean of Texas. Storeria sp. is reported from the Ir• Coluber Dekayi Holbrook, "1836" (probably 1839):121. Type-lo• vingtonian and Rancholabrean of Kansas (Brattstrom, 1967), and cality, "Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, Louisiana"; the Rancholabrean of Virginia (Guilday, 1962), and Pennsylvania restricted by Trapido (1944) to "Massachusetts," and by (Guilday et al., 1964; Richmond, 1964). Schmidt (1953) to "Cambridge, Massachusetts." See Re• • PERTINENT LITERATURE. Trapido (1944) wrote the most marks. Only known syntype (Acad. Natur. Sci. Philadelphia complete account of the species. Subsequent taxonomic contri• 5832) designated lectotype by Trapido (1944) and erroneously butions have included: Neill (195Oa), who considered S. victa a referred to as holotype by Malnate (1971); adult female, col• lector, and date unknown (not examined by author). subspecies of dekayi, Anderson (1961), who resurrected Cope's C[oluber] ordinatus: Storer, 1839:223 (part). S. tropica, and Sabath and Sabath (1969), who returned tropica to subspecific status. Stuart (1954), Bleakney (1958), Savage (1966), Tropidonotus Dekayi: Holbrook, 1842 Vol. IV:53. Paulson (1968), and Christman (1980) reported on variation and Tropidonotus occipito-maculatus: Holbrook, 1842:55 (inserted ad- zoogeography. Other distributional reports include: Carr (1940), denda slip). -

The Herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: a Bibliography

The Herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: A Bibliography Revised 2 nd Edition Brian S. Gray and Mark Lethaby Special Publication of the Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center, Number 1 2 Special Publication of the Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center The Herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: A Bibliography Revised 2 nd Edition Compiled by Brian S. Gray [email protected] and Mark Lethaby Natural History Museum at the Tom Ridge Environmental Center, 301 Peninsula Dr., Suite 3, Erie, PA 16505 [email protected] Number 1 Erie, Pennsylvania 2017 Cover image: Smooth Greensnake, Opheodrys vernalis from Erie County, Pennsylvania. 3 Introduction Since the first edition of The herpetology of Erie County, Pennsylvania: a bibliography (Gray and Lethaby 2012), numerous articles and books have been published that are pertinent to the literature of the region’s amphibians and reptiles. The purpose of this revision is to provide a comprehensive and updated list of publications for use by researchers interested in Erie County’s herpetofauna. We have made every effort to include all major works on the herpetology of Erie County. Included are the works of Atkinson (1901) and Surface (1906; 1908; 1913) which are among the earliest to note amphibians and or reptiles specifically from sites in Erie County, Pennsylvania. The earliest publication to utilize an Erie County specimen, however, may have been that of LeSueur (1817) in his description of Graptemys geographica (Lindeman 2009). While the bibliography is quite extensive, we did not attempt to list everything, such as articles in local newspapers, and unpublished reports, although some of the more significant of these are included. -

Indigenous and Established Herpetofauna of Northwest Louisiana

Indigenous and Established Herpetofauna of Northwest Louisiana Non-venomous Snakes (25 Species) For more info: Buttermilk Racer Coluber constrictor anthicus 318-773-9393 Eastern Coachwhip Coluber flagellum flagellum www.learnaboutcritters.org Prairie Kingsnake Lampropeltis calligaster [email protected] Speckled Kingsnake Lampropeltis holbrooki www.facebook.com/learnaboutcritters Western Milksnake Lampropeltis gentilis Northern Rough Greensnake Opheodrys aestivus aestivus Alligator (1 species) Western Ratsnake Pantherophis obsoletus American Alligator Alligator mississippiensis Slowinski’s Cornsnake † Pantherophis slowinskii Flat-headed Snake † Tantilla gracilis Western Wormsnake † Carphophis vermis Lizards (10 Species) Mississippi Ring-necked Snake Diadophis punctatus stictogenys Western Mudsnake Farancia abacura reinwardtii Northern Green Anole Anolis carolinensis Eastern Hog-nosed Snake Heterodon platirhinos Prairie Lizard Sceloporus consobrinus Mississippi Green Watersnake Nerodia cyclopion Southern Coal Skink † Plestiodon anthracinus pluvialis Plain-bellied Watersnake Nerodia erythrogaster Common Five-lined Skink Plestiodon fasciatus Broad-banded Watersnake Nerodia fasciata confluens Broad-headed Skink Plestiodon laticeps Graham's Crayfish Snake Regina grahamii Southern Prairie Skink † Plestiodon septentrionalis obtusirostris Gulf Swampsnake Liodytes rigida sinicola Little Brown Skink Scincella lateralis Dekay’s Brownsnake Storeria dekayi Eastern Six-lined Racerunner Aspidoscelis sexlineata sexlineata Red-bellied Snake -

Checklist of Grundy County Missouri Amphibians and Reptiles for 2020

X = Recent collection (1987 or after) Checklist of Grundy County Missouri Amphibians and Reptiles for 2020 / = Historical collection (before 1987) Western Lesser Siren Mole Salamander Three-toed Amphiuma Four-toed Salamander Siren intermedia Ambystoma talpoideum Amphiuma tridactylum Hemidactylium scutatum Hellbender Small-mouthed Salamander Long-tailed Salamander Western Slimy Salamander Cryptobranchus alleganiensis Ambystoma texanum Eurycea longicauda Plethodon albagula Ringed Salamander Eastern Tiger Salamander Cave Salamander Ozark Zigzag Salamander Ambystoma annulatum / Ambystoma tigrinum Eurycea lucifuga Plethodon angusticlavius Spotted Salamander Central Newt Grotto Salamander Southern Red-backed Salamander Ambystoma maculatum Notophthalmus viridescens Eurycea spelaea Plethodon serratus Marbled Salamander Mudpuppy Oklahoma Salamander Ambystoma opacum Necturus maculosus Eurycea tynerensis Eastern Spadefoot Cope's Gray Treefrog Boreal Chorus Frog Southern Leopard Frog Scaphiopus holbrookii Hyla chrysoscelis Pseudacris maculata X Lithobates sphenocephalus Plains Spadefoot Green Treefrog Northern Crawfish Frog Wood Frog Spea bombifrons Hyla cinerea Lithobates areolatus Lithobates sylvaticus American Toad Gray Treefrog Plains Leopard Frog Eastern Narrow-mouthed Toad X Anaxyrus americanus / Hyla versicolor / Lithobates blairi Gastrophryne carolinensis Great Plains Toad Spring Peeper American Bullfrog Western Narrow-mouthed Toad Anaxyrus cognatus Pseudacris crucifer / Lithobates catesbeianus Gastrophryne olivacea Fowler's Toad Upland Chorus -

Eastern Wormsnake Carphophis Amoenus

Natural Heritage Eastern Wormsnake & Endangered Species Carphophis amoenus Program State Status: Threatened www.mass.gov/nhesp Federal Status: None Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife DESCRIPTION: Eastern Wormsnakes are small, glossy, thin snakes, and range from 18-37 cm (7-14.5 inches) in length. The body is unpatterned, gray or tan to dark brown. Distinguishing characteristics include a slightly flattened and pointed nose, small eyes, and a pink venter. Venter coloration extends onto sides of body to include 1st to 2nd scale rows. The tail length is short and has a blunt spine-like tip. The body typically has 13 scale rows. The scales are unkeeled and the annual plate is divided. They are a non-venomous snake in the Coluidae family. Based on research conducted in Kentucky, females Eastern Wormsnakes are slightly larger than males (mass: F = about 6.6g, M = about 4.6g); number of ventral scales (F = 112-150, M = 106-138). However, Copyright J.D.Wilson, 2006; www.discoverlife.org males have a longer tail length/body length (F = 11.3- 20.3, M = 13.4-20.4) and greater average number of SIMILAR SPECIES IN MASSACHUSETTS: There subcaudal scales (F = 14-36, M = 25-40). are three small snakes in Massachusetts that may be confused with the Eastern Wormsnake. The little brown Juveniles look like adults but the pattern is darker brown snake (Storeria dekayi) has a faint pattern of parallel and the venter brighter pink. spotting on the dorsum and lacks a pointed snout. The ring-necked snake (Diadophis punctatus) has a distinct cream or yellow colored ring across the neck and a cream colored venter; some have black crescent-shaped spots down the mid-venter. -

Venomous Nonvenomous Snakes of Florida

Venomous and nonvenomous Snakes of Florida PHOTOGRAPHS BY KEVIN ENGE Top to bottom: Black swamp snake; Eastern garter snake; Eastern mud snake; Eastern kingsnake Florida is home to more snakes than any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. Since only six species are venomous, and two of those reside only in the northern part of the state, any snake you encounter will most likely be nonvenomous. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission MyFWC.com Florida has an abundance of wildlife, Snakes flick their forked tongues to “taste” their surroundings. The tongue of this yellow rat snake including a wide variety of reptiles. takes particles from the air into the Jacobson’s This state has more snakes than organs in the roof of its mouth for identification. any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. They are found in every Fhabitat from coastal mangroves and salt marshes to freshwater wetlands and dry uplands. Some species even thrive in residential areas. Anyone in Florida might see a snake wherever they live or travel. Many people are frightened of or repulsed by snakes because of super- stition or folklore. In reality, snakes play an interesting and vital role K in Florida’s complex ecology. Many ENNETH L. species help reduce the populations of rodents and other pests. K Since only six of Florida’s resident RYSKO snake species are venomous and two of them reside only in the northern and reflective and are frequently iri- part of the state, any snake you en- descent. -

Understanding Patterns of Snake (Colubridae; Storeria) Movement and Road Mortality in a State Park Iwo P

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Student Honors Theses Biological Sciences Spring 2013 Taking the road most travelled: Understanding patterns of snake (Colubridae; Storeria) movement and road mortality in a state park Iwo P. Gross Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/bio_students Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Gross, Iwo P., "Taking the road most travelled: Understanding patterns of snake (Colubridae; Storeria) movement and road mortality in a state park" (2013). Student Honors Theses. 3. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/bio_students/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Taking the road most travelled: Understanding patterns of snake (Colubridae; Storeria) movement and road mortality in a state park by Iwo P. Gross HONORS THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES WITH HONORS AT EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS May 2013 I hereby recommend that this Honors Thesis be accepted as fulfilling this part of the undergraduate degree cited above: Thesis Director Date Department Chair Date ABSTRACT Roadways negatively affect their surrounding ecosystems through the contamination of air, water, and soil resources, the dissection of populations and habitat areas, and the direct mortality of several fauna. My study assessed the significance of a number of variables that might influence the temporal and spatial patterns of road mortality in a population of Midland Brownsnakes (Storeria dekayi wrightorum). -

Great Dismal Swamp Northern Brown Snake

Snakes Toads and Frogs Brown water snake................................Nerodia taxispilota Eastern spadefoot..............Scaphiopus holbrooki holbrooki U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Red-bellied water snake...................Nerodia erythrogaster American toad...........................................Bufo americanus erythrogaster Southern toad................................................Bufo terrestris Northern water snake...................Nerodia sipedon sipedon Fowler’s toad................................Bufo woodhousii fowleri Great Dismal Swamp Northern brown snake... ..................Storeria dekayi dekayi Oak toad.......................................................Bufo quercicus Northern red-bellied snake.........Storeria occipitomaculata Spring peeper........................................Pseudacris crucifer National Wildlife Refuge occipitamaculata Pinewoods tree frog......................................Hyla femoralis Eastern ribbon snake.............Thamnophis sauritus sauritus Squirrel tree frog...........................................Hyla squirella Eastern garter snake.................Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis Gray tree frog..............................................Hyla versicolor Eastern earth snake.....................Virginia valeriae valeriae Little grass frog....................................Pseudacris ocularis Animals of the Eastern hognose snake...Heterodon platirhinos platirhinos Upland chorus frog..............Pseudacris triseriata feriarum Southern ringneck snake....Diadophis punctatus punctatus -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: COLUBRIDAE Storeria

900.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: COLUBRIDAE Storeria Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Ernst, C.H. 2012. Storeria . Storeria Baird and Girard American Brownsnakes Coluber : Linnaeus 1758:216. See Remarks . Storeria Baird and Girard 1853:135. Type -species, Tropidonotus dekayi Holbrook 1842:135 (officially so designated by the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature [ICZN] 1962:145; see Remarks ). Ischnognathus Duméril 1853:468. Type -species, FIGURE 1. Storeria dekayi texana . Photograph by Suzanne L. Tropidonontus dekayi Holbrook 1842:53) Collins. Tropidoclonium : Cope 1865:190. Hemigenius Dugès 1888:182. Type -species, Hemi- genius variabilis Dugès 1888:182 (= Tropidoclo- nium storerioides Cope 1865:190). Natrix : Cope 1889:391. Tropidonotus : Duméril, Bocourt, and Mocquard 1893: 750. Thamnophis : Amaral 1929:21. Tropidoclonion : Dunn 1931:163. Storeia : Gray 2004:94. Ex errore . • CONTENT . Four species are recognized: Storeria FIGURE 2. Storeria hidalgoensis . Photograph by Michael S. dekayi, Storeria hidalgoensis, Storeria occipidomacu - Price. lata , and Storeria storerioides . See Remarks . • DEFINITION . Snakes of the genus Storeria are slender, cylindrical, relatively short (max. TL 40.6 cm), live -bearing, terrestrial worm and slug predators. Trunk vertebrae are small and elongate, with vault - ed neural arches containing well developed low spines that extend posteriorly beyond the arch. The somewhat pointed hypapophyses is also directed posteriorly. Condyles and cotyles are usually round, with lateral forimina present on the cotyles. The pre- zygapophyseal accessory processes are well devel - oped. A distinct haemal keel and subcentral ridges are present; and paired lateral processes occur on some caudal vertebrae. In the skull, the dentary bone is essentially not motile on the articular. FIGURE 3. Storeria occipitomaculata occipitomaculata . -

Amphibians and Reptiles Of

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Amphibians and Reptiles of Aransas National Wildlife Refuge Abundance Common Name Abundance Common Name Abundance C Common; suitable habitat is available, Scientific Name Scientific Name should not be missed during appropriate season. Toads and Frogs Texas Tortoise R Couch’s Spadefoot C Gopherus berlandieri U Uncommon; present in moderate Scaphiopus couchi Guadalupe Spiny Soft-shelled Turtle R numbers (often due to low availability Hurter’s Spadefoot C Trionyx spiniferus guadalupensis of suitable habitat); not seen every Scaphiopus hurteri Loggerhead O visit during season Blanchard’s Cricket Frog U Caretta caretta Acris crepitans blanchardi Atlantic Green Turtle O O Occasional; present, observed only Green Tree Frog C Chelonia mydas mydas a few times per season; also includes Hyla cinerea Atlantic Hawksbill O those species which do not occur year, Squirrel Tree Frog U Eretmochelys imbricata imbricata while in some years may be Hyla squirella Atlantic Ridley(Kemp’s Ridley) O fairly common. Spotted Chorus Frog U Lepidocheyls kempi Pseudacris clarki Leatherback R R Rare; observed only every 1 to 5 Strecker’s Chorus Frog U Dermochelys coriacea years; records for species at Aransas Pseudacris streckeri are sporadic and few. Texas Toad R Lizards Bufo speciosus Mediterranean Gecko C Introduction Gulf Coast Toad C Hemidactylus turcicus turcicus Amphibians have moist, glandular skins, Bufo valliceps valliceps Keeled Earless Lizard R and their toes are devoid of claws. Their Bullfrog C Holbrookia propinqua propinqua young pass through a larval, usually Rana catesbeiana Texas Horned Lizard R aquatic, stage before they metamorphose Southern Leopard Frog C Phrynosoma cornutum into the adult form.