Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012-Dubliners-Programme.Pdf

DUBLIN: ONE CITY, ONE BOOK: EVENTS (continued) ABOUT THE BOOK JOYCEAN TOUR OF GLASNEVIN CEMETERY FARMLEIGH, CASTLEKNOCK Dubliners is Joyce at his most direct and his most accessible. Any reader Following upon Dublin’s designation as Glasnevin Cemetery, the heart of the James Joyce in the Phoenix Park may pick it up and enjoy these fifteen stories about the lives, loves, small UNESCO City of Literature, what more Hibernian necropolis, has many links to Area – exhibition of rare books from the triumphs and great failures of its ordinary citizens without the trepidation James Joyce’s life and writing. From the Benjamin Iveagh Library. Wed-Sun & appropriate title could there be for Dublin: Hades Chapter in Ulysses, which takes Bank Holidays from 1 April. 10am-4.30pm that might be felt on opening, say, Ulysses, famed for its impenetrabil- One City, One Book 2012 than James place in the cemetery, to the family grave as part of the guided tour. Further ity and stream-of-consciousness hyperbole. At the same time, although Joyce’s DUBLINERS! which is the final resting place of his information Tel: 01 8155981 Also Joycean simply written, there is great depth and many levels to the stories, in parents; walk through the life, time and exhibition by contemporary Japanese which the characters – young, middle-aged and old – are revealed, to imagination of James Joyce. photographer Motoko Fujita. Admission Joyce is the city’s most celebrated lit- Daily throughout April at 1pm. Tickets free themselves, or sometimes only to the reader, in all their frail humanity. erary son and his masterly collection €10 include a visit to Glasnevin Museum THE JAMES JOYCE CENTRE, 35 NORTH GREAT •The Sisters•An Encounter•Araby•Eveline•After the Race•Two Gallants• of short stories gives a remarkable JOYCEAN WALKING TOURS GEORGE’S STREET insight into the lives of a disparate group of Dublin citizens in the early Echoes of Joyce’s Dublin. -

Irland Journal 1.90 Irland Journal 2.90

Best-Nr.: 18143088 irland journal 1.90 Inhaltsverzeichnis ij 1.90 4 - auf entdeckungsreise: Das verlorene Erbe der Blaskets 50 - Das gerechteste Wahlsystem der Welt? Impressionen irischer Institutionen 44 - Krieg ohne Ende: 20 Jahre britische Truppen in Nordirland 14 - literatur aus irland: Midland (Rita Kelly) 76 - Nischt als Joyce 35 - Portfolio Derek Speirs Best-Nr.: 18143089 irland journal 2.90 Inhaltsverzeichnis ij 2.90 6 -auf entdeckungsreise: Versteinertes Chaos. Line Reise, zum Giant's Causeway 50 -Beobachtungen, Meinungen, Momentaufnahmen - Die Bilder Rita Duffys 70 -das interview: Wer war Brian O'Nolan? 22 -Es darf gekickt werden. Irlands unbekannte Fußballwelt 61 -Feten Feiern Festivals: Der Inselsommer 1990 41- Frauenbilder: Ein starkes Stück Frau 36 -Keine Bestenliste: Irland-Reiseführer 46 -Zur Frauenbewegung und zur Situation irischer Frauen heute Best-Nr.: 18143090 irland journal 3.90 Inhaltsverzeichnis ij 3.90 38 -Dann plötzlich...fiel der Boden aus seiner Welt 23 -auf entdeckungsreise: "Unmöglich, sie alle vom Tal fernzuhalten." Glendalough: Kein Geheimtip 12 -auf entdeckungsreise: von Dublin nach Shannon Harbour. Eine Fahrt auf dem Grand Canal 61 -Gegenbilder (1): Deutschsprachige Autoren über Irland: Karl Marx und Friedrich Engels: Ein Land der Ruinen 56 -Rita Ann Higgins: Collin und Hexe Best-Nr.: 18143091 irland journal 4.90 Sonderheft zur Wahl von Mary Robinson zur Irischen Staatspräsidentin Die Sonderausgabe ist komplett der Wahl Mary Robinsons zur Präsidentin der Republik Irland gewidmet. Best-Nr.: 18143092 irland -

News/Announcements - Archives – Olivier Cornet Gallery

NEWS/ANNOUNCEMENTS - ARCHIVES – OLIVIER CORNET GALLERY 2018 Friday 28th December 2018 The Olivier Cornet Gallery is delighted to read in The Irish Times that Conrad Frankel's show 'Road Trip', which took place at the gallery in September this year, is listed in Aidan Dunne's round up of his favourite art exhibitions of 2018. ----------------- Friday 14th December 2018 The Olivier Cornet Gallery is delighted to announce that two paintings by the Irish poet and artist Paula Meehan (Monto Karma III and Monto Karma IV) which we exhibited as part of our Bloomsday 2018 show 'Drawing on Joyce', have just joined the collection of MoLI, the Museum of Literature Ireland. Last year, 'An Piarsach', Eoin Mac Lochlainn's painting of his great grand uncle Patrick Pearse, joined the permanent collection of the Pearse Museum in Rathfarnham and back in 2016, Yanny Petters's 'Teasel for finches, November', joined the Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art, in Kew Gardens, London. It is always a great honour for our gallery when works by the artists we work with, join museum collections and therefore remain available to the public. ----------------- Sunday 25th November 2018 The Olivier Cornet Gallery is delighted to announce that 'Somewhere between perception and reality', our Winter group show first presented at the VUE Art Fair in November 2018 will open at the gallery on 9th December and will run till 17th February. ----------------- Sunday 21st October 2018 The Olivier Cornet Gallery is delighted to announce that gallery artist Claire Halpin has just been shortlisted for the Savills Prize 2018. The overall winner will be announced at the opening of VUE Art Fair, RHA Dublin, on Thursday 1st November. -

A Complete Guide to All Dublin Attractions

Dublin A Complete Guide to All Dublin Attractions © 2014-2017 visitacity.com All rights reserved. No part of this site may be reproduced without our written permission. Ha'Penny Bridge Ha'Penny Bridge or Half Penny Bridge crosses Liffey Street Lower to Merchants Arch. The elliptical arched metal bridge originally had a wooden gangway when it was constructed in 1816. The bridge has a 43 meter span, 3 meter width and is 3 meters above the water. Today 30,000 people walk across the bridge every day! Before the bridge was built people would take ferries across the river. The ferries were often overcrowded and sometimes even capsized. When the bridge was constructed the ferries became redundant. William Walsh was the former ferry owner and a city alderman. He was compensated with £3,000 and a lease on the bridge for 100 years. Walsh charged Dubliners Image By: HalfPennyBridge-Public Domain a ha'penny to cross the bridge, which was the same price he had charged Image Source: for a ferry ride. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ha'penny_Bridge#mediaviewer/File:HalfPennyBridge.jpg The bridge gets its name from the ha'penny toll but officially it has been called the Liffey Bridge since 1922. It is also known as Triangle, Iron Bridge and Wellington. The bridge remained the only pedestrian bridge crossing the Liffey River until Millennium Bridge was built in 1999. Address: Ha'penny Bridge, Dublin, Ireland Transportation: Luas: Jervis. Bus: 39B, 51, 51B, 51C, 51D, 51X, 68, 69, 69X, 78, 78A, 79, 79A, 90, 92, 206 © 2014-2017 visitacity.com All rights reserved. -

Joyce's Dublin

1 James Joyce Centre Mater Misericordiae NORTH CIRCULAR ROAD 2 Belvedere College Hospital A MAP OF 1904 MAP OF 3 St George’s Church 4 7 Eccles St BELVEDERE PLACE ROAD ECCLES STREET 5 Glasnevin Cemetery 6 Gresham Hotel R.C.Ch Joyce’sRICHMOND PLACE 7 The Joyce Statue 4 8 O’ConnellCharleville Bridge Mall 3 Free 9 Night Town Ch. Dublin St. George’s 10 Cabman’s shelter Nelson St. STREET Church Upr. Rutland St. 11 North Wall Quay BLESSINGTON STREET 12 Clarence St. Temple St. PORTLAND Sweny’s ROW Chemist PHIBSBOROUGH 13 The National Maternity MOUNTJOY SQUARE Hospital D O R S E T Wellington St. 14 Finn’s Hotel BUCKINGHAM FREDERICK STREET 2 ERHILL 15 The National Library Hardwicke St. Hill St. 16 Davy Byrnes T MID. GARDIN E 17 UCD Newman House E Nth.Gt.George’s St. SUMM R STREET 18 The Volta Cinema T Grenville St. S 19 Barney Kiernan’s Pub Y GREAT DENMARK STREET O 20 Ormond Hotel J STREET T CAVENDISH ROW 1 Empress Place N E R S T. 21 The Dead House L B R O A D S T O N E U L 22 Sandymount Strand S T A T I O N I DOMINICKO 19 H M Cumberland St. 23 Sandycove Tower SEVILLE PLACE N G R A N B Y R O W O 24 The School I T RUTLAND NORTH STRAND Oriel St. MARLBOROUGH ST. Tramlines in 1904 U Granby Lane SQUARE LWR. GARDINER ST. T GLOUCESTER STREET I Henrietta St. STREET T Rotunda TYRONE STREET S M A B B O T S T. -

Theatre 471-002: Irish Theatre and Culture Rick Jones Griffith 303, Daily, 9-12 (Time Shared with THR 471.1) Summer I, 2016

Theatre 471-002: Irish Theatre and Culture Rick Jones Griffith 303, Daily, 9-12 (time shared with THR 471.1) Summer I, 2016 Course overview: This course emphasizes the relationship between Irish theatre and the culture: that is, between theatre and other arts, between theatre and histori-political events, etc. The course will be taught in conjunction with THR 471.1: Irish Theatre and Drama. Since all students enrolled for one course must also enroll for the other, there may be some trade- offs of time between the two courses. This half of the sequence is primarily experiential, i.e. centered primarily on the fact of being in Ireland. While there is a clear academic intent to the course, the emphasis is on the act of engaging with Irish culture rather than on the articulation of that engagement. Prerequisites: Sophomore standing or above; ENG 132 and THR 162 with grades of C or better, or permission of instructor. Concurrent registration in THR 471.1. Course fees as determined by the Office of International Studies and Programs. Contacting me: Office: 217 Fine Arts, ext. 1290 (department office is room 212, ext. 4003). I will be available immediately following class every day, and by appointment. In Ireland, of course, other arrangements can/will be made. My cell phone # will be distributed in class (emergencies only while abroad, please). E-mail: My SFA e-mail address is [email protected]. This is my preferred means of contact (while in the US). I check e-mail at least three times a day. I do receive literally dozens of e-mail messages each day: please include the prefix “471” (e.g., “471: problems with paper”) in the subject line of all messages so I’ll recognize you immediately as a student in this class. -

Copyrighted Material

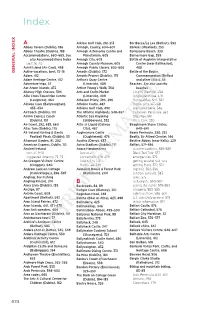

Index Galway City, 340, 342–344 • A • Iveragh Peninsula, 284–285 AARP, 84 Killarney, 273, 275–276 Abbey Bed & Breakfast, 404 Kinsale, 257–260 Abbey House, 226 Limerick City, 312–313 Abbey Theatre, 165 North Antrim, 433–434 Abby Taxis, 340 prices of, 80–81 ABC Guesthouse, 116 Ring of Kerry, 284–285 Abocurragh Farm Guesthouse, 412 Tralee, 294–296 Accessible Journeys, 85 types, 76–80 accommodations West County Cork, 257–260 Adare, 312–313 Ace Cabs, 379 Aran Islands, 356 Achill Island, 374–375 Belfast, 421, 423–424 Adare, 310–318 best of, 13–15 Adare Heritage Centre and booking, 76–82 Desmond Castle, 316 budget planning for, 55 Adare Manor Hotel and Golf Resort, caravans, 80 312–313 Connemara, 358–361 Adelphi Portrush hotel, 433 Cork City, 241–243 Aer Arann, 355, 372, 379, 403 cost cutting, 57 Aer Lingus, 64, 67, 340, 456 County Clare, 321–324 Aghadoe Heights hotel, 273 County Derry, 404, 406, 408 Aherne’s restaurant, 243 County Donegal, 392–394 Ailwee Cave, 330–331 County Down, 441–442 Air Canada, 64, 456 County Fermanagh, 412–413 air travel. See also specific locations County Kildare, 193 airfare, getting best deal, 64–65 County Kilkenny, 226–227 airlines, 64, 456 County Louth, 170–171 airports, 63–64. See also specific County Mayo, 372–373 airports County Meath, 170–171 budget planning for, 55 County Sligo,COPYRIGHTED 379–380, 382 security, MATERIAL 97–98 County Tipperary, 220–221 AirCoach, 102 County Tyrone, 412–413 Airfarewatchdog (Web site), 65 County Waterford, 212–214 Alamo, 456 County Wexford, 202–203 Albert Memorial Clock, 429 County -

Copyrighted Material

Index A Arklow Golf Club, 212–213 Bar Bacca/La Lea (Belfast), 592 Abbey Tavern (Dublin), 186 Armagh, County, 604–607 Barkers (Wexford), 253 Abbey Theatre (Dublin), 188 Armagh Astronomy Centre and Barleycove Beach, 330 Accommodations, 660–665. See Planetarium, 605 Barnesmore Gap, 559 also Accommodations Index Armagh City, 605 Battle of Aughrim Interpretative best, 16–20 Armagh County Museum, 605 Centre (near Ballinasloe), Achill Island (An Caol), 498 Armagh Public Library, 605–606 488 GENERAL INDEX Active vacations, best, 15–16 Arnotts (Dublin), 172 Battle of the Boyne Adare, 412 Arnotts Project (Dublin), 175 Commemoration (Belfast Adare Heritage Centre, 412 Arthur's Quay Centre and other cities), 54 Adventure trips, 57 (Limerick), 409 Beaches. See also specifi c Aer Arann Islands, 472 Arthur Young's Walk, 364 beaches Ahenny High Crosses, 394 Arts and Crafts Market County Wexford, 254 Aille Cross Equestrian Centre (Limerick), 409 Dingle Peninsula, 379 (Loughrea), 464 Athassel Priory, 394, 396 Donegal Bay, 542, 552 Aillwee Cave (Ballyvaughan), Athlone Castle, 487 Dublin area, 167–168 433–434 Athlone Golf Club, 490 Glencolumbkille, 546 AirCoach (Dublin), 101 The Atlantic Highlands, 548–557 Inishowen Peninsula, 560 Airlink Express Coach Atlantic Sea Kayaking Sligo Bay, 519 (Dublin), 101 (Skibbereen), 332 West Cork, 330 Air travel, 292, 655, 660 Attic @ Liquid (Galway Beaghmore Stone Circles, Alias Tom (Dublin), 175 City), 467 640–641 All-Ireland Hurling & Gaelic Aughnanure Castle Beara Peninsula, 330, 332 Football Finals (Dublin), 55 (Oughterard), -

Exploring Ireland: Through Its Literature, Drama, Film & History

AHA SUMMER PROGRAM DUBLIN, 2013 EXPLORING IRELAND: THROUGH ITS LITERATURE, DRAMA, FILM & HISTORY With four Nobel Prize winners, Ireland can claim her place on the world cultural stage. Students who participate in Exploring Ireland will experience the rich heritage of its history, theatre, literature, and film through three course options, which contextualize their creative material in relation to Ireland’s socio-cultural history. Dublin provides the backdrop for the Program – in an exciting, dynamic, young and diverse way. “When I die Dublin will be written in my heart” – James Joyce www.academicoptionsireland.com [email protected] AHA SUMMER PROGRAM, DUBLIN, 2013 EXPLORING IRELAND: THROUGH ITS LITERATURE, DRAMA, FILM AND HISTORY IADT - Location of the AHA administrator. Having formed her own company in 1999, Academic & Language Summer Program Options she has worked in partnership with AHA since 2003 to bring quality learning Currently educating just under 3,000 students, programs to American university students. IADT’s educational structure is unique to Una is responsible for managing the day Ireland. The college prides itself on being the to day operations on site and placement of only Institute for Art, Design & Technology students in home stay families. She is readily hence its abbreviated title. Divided into three available to help answer students’ questions Schools, The School of Creative Arts, The about living and studying abroad in Ireland. School of Creative Technologies and The School of Business and Humanities, IADT is Daniel Dwyer, Assistant Site Director also home to the internationally recognized National Film School. Daniel has been working full time on the AHA program since 2008, He holds BA Hons in The campus contains a number of modern Business & Arts Management from IADT. -

Dublin City (Dublin County Borough) Development Board, Jan, 2002 Dublin City Profile (Dublin County Borough)

National Institute for Regional and Spatial Analysis NIRSA Working Paper Series No. 15 January 2002 Dublin City Profile (Dublin County Borough) Prepared for DUBLIN CITY DEVELOPMENT BOARD By Jim Walsh, Joe Brady and Chris Mannion NIRSA National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Maynooth, Co. Kildare Ireland i Report for the Dublin City (Dublin County Borough) Development Board, Jan, 2002 Dublin City Profile (Dublin County Borough) Prepared for DUBLIN CITY DEVELOPMENT BOARD By Prof. Jim Walsh, Dr. Joe Brady & Chris Mannion THE NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR REGIONAL AND SPATIAL ANALYSIS (NIRSA) NUI MAYNOOTH i Report for the Dublin City (Dublin County Borough) Development Board, Jan, 2002 Foreword This Report is divided into two parts the main or first part is the written text divided into eight chapters. Part two is an accompanying Book of Maps, which have been bound separately for easy reference. Part One Chapter 1 introduces the aims of the report and outlines the role Dublin City has on both a regional and national level. Chapter 2 has a brief description of the physical landscape together with some pertinent facts required by the Shared Vision Project. The distribution and location of the physical heritage of Dublin City with regard to Archaeological Sites & National Monuments, National Heritage Areas and Special Areas of Conversation are also detailed in this chapter. Chapter 3 is a Classification of socio-economic areas in Dublin City and County or Greater Dublin Area using primarily data from the 1996 Census of Population. In addition ‘a typology’of Dublin City and County or Greater Dublin Area is given using the census of population statistics. -

Business to Arts Developing Creative Partnerships

Business to Arts | Developing Creative Partnerships Lower Ground Floor 17 Kildare Street Dublin 2 D02 P766 T +353 1 662 9238 W businesstoarts.ie E [email protected] Our Patrons Our Members Our Friends Accenture A&L Goodbody Justin Bickle AIB Group Alan McNab Andrew Crotty Allianz Ireland Alternatives Group Clare Duignan Anonymous Amorys Solicitors Andrew Fleming Arthur Cox An Post David Fitzsimons Bank of America Merrill Lynch ARDEX Building Products Mary Fulton Bank of Ireland Group Behaviour & Attitudes Andrew Hetherington BSkyB BNP Paribas Noel Hiney daa Design & Crafts Council of Jeanne Kelly Deloitte Ireland Kevin Kent Department of Arts, Heritage & the Diageo Ireland Ursula Murphy Gaeltacht Ecclesiastical Rowena Neville Dublin City Council Etsy Clodagh O’Brien Dublin Institute of Technology EY Brendan O’Mara Dublin Port Company Genesis Michael Owens ESB Graepel Perforators & Weavers Davina Saint The Ireland Funds Hamilton House Irish Life Group Image Now KPMG IMRO Sky Ireland Our Clients Irish Times Training TileStyle KBC Bank Dublin Port Company Mason Hayes & Curran DLR CoCo Mazars ID2015 McCann FitzGerald Savills John McGrane Sky Arts Stuart McLaughlin XL Catlin MERC Partners Merrion Hotel Dublin NCAD National University of Ireland, Galway Press Up Entertainment Group PricewaterhouseCoopers Q4PR RDS Foundation RTÉ Salesforce.com Terroirs The Copper House Gallery The Doyle Collection The Marketing Institute Vhi Healthcare Walkers Zurich Insurance Business to Arts | Developing Creative Partnerships Lower Ground Floor 17 Kildare Street Dublin 2 D02 P766 T +353 1 662 9238 W businesstoarts.ie E [email protected] Arts Affiliates Access Cinema IMMA Smock Alley Theatre Adrienne Brown Improvised Music Company St. -

2008 in the National Library of Ireland

Page 1 of 48 2008 in the National Library of Ireland Our Mission To collect, preserve, promote and make accessible the documentary and intellectual records of the life of Ireland and to contribute to the provision of access to the larger universe of recorded knowledge. Page 2 of 48 Report of the Board of the National Library of Ireland For the year ended 31 December 2008 To the Minister for Arts, Sport & Tourism pursuant to section 36 of the National Cultural Institutions Act 1997. Published by National Library of Ireland ISSN 2009-020X (c) Board of the National Library of Ireland, 2009 Page 3 of 48 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD OVERVIEW 2008 Progress towards: Strategic aims and objectives Developing and safeguarding collections Quality service delivery Achieving outreach, collaboration and synergy Improving the physical infrastructure Developing staff Developing the organisation BOARD AND COMMITTEES OF THE BOARD APPENDICES: Appendix 1: Thanks to our sponsors and donors Appendix 2: National Library of Ireland Society Appendix 3: Visitor numbers and other statistics Appendix 4: Collaborative Partnerships in 2008 Page 4 of 48 Chairman’s Statement As Chairman of the Board of the National Library of Ireland I am pleased to present this, the Board’s fourth annual report, which summarises significant developments in the Library in 2008. The year marked a period of consolidation, with continuing investment in acquisitions and in digitisation and related IT infrastructural initiatives. Services continued to be developed and improved, and a wide range of events and activities took place in the Library. Considerable progress was made during the year in achieving many of the goals and objectives set out in the Library’s Strategic Plan 2008–2010.