Council Meeting Held on 6/19/2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making a Community: Filipinos in Wellington

Making a Community: Filipinos in Wellington September 2017 ISBN 978-0-9941409-4-4 (PDF) Making a Community: Filipinos in Wellington About the Author As an American living in New Zealand, I’ve been observing the debate here on immigration and multiculturalism. I arrived in Wellington last year with my Kiwi husband and three-year old son – and while settling in we’ve spent a lot of time discovering the delights of the city and its people. The experience also gave me some perspective on being a migrant far from home. I have a professional interest in South East Asian history, languages and culture - I just completed a PhD on the subject. I speak some Filipino, and am fascinated by the Philippines’ complex history. One of the major phenomena in the Philippines since the 1970s has been the growth of the global Filipino diaspora. That story has often been full of sadness. So I was intrigued by anecdotes of positivity and success from Wellington. Writing about how the migrant Filipino community has settled in New Zealand has been more than just a research project. It has highlighted how migration plays a role in community building. It also has meaning for me and my family’s future here. I really wanted to share some of the stories that I think reflect successful outcomes from immigration over the past thirty years. By Dr Rebecca Townsend 1 Key Points 1. 2. 3. Filipinos comprise 1 percent of Filipinos are a vital part of Most Filipinos in New Zealand are New Zealand’s population – the New Zealand’s dairy, healthcare, not Overseas Filipino Workers third largest Asian ethnic group construction, nursing, aged care, (OFW). -

General Distribution and Characteristics of Active Faults and Folds in the Mackenzie District, South Canterbury D.J.A

General distribution and characteristics of active faults and folds in the Mackenzie District, South Canterbury D.J.A. Barrell D.T. Strong GNS Science Consultancy Report 2010/147 Environment Canterbury Report No. R10/44 June 2010 DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited (GNS Science) exclusively for and under contract to Environment Canterbury. Unless otherwise agreed in writing by GNS Science, GNS Science accepts no responsibility for any use of, or reliance on, any contents of this report by any person other than Environment Canterbury and shall not be liable to any person other than Environment Canterbury, on any ground, for any loss, damage or expense arising from such use or reliance. The data presented in this report are available to GNS Science for other use from June 2010 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Barrell, D.J.A., Strong, D.T. 2010. General distribution and characteristics of active faults and folds in the Mackenzie District, South Canterbury. GNS Science Consultancy Report 2010/147. 22 p. © Environment Canterbury Report No. R10/44 ISBN 978-1-877574-18-4 Project Number: 440W1435 2010 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................II 1. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................1 2. INFORMATION SOURCES .........................................................................................2 3. GEOLOGICAL OVERVIEW -

Notes Subscription Agreement)

Amendment and Restatement Deed (Notes Subscription Agreement) PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited Issuer The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 Subscribers 3815658 v5 DEED dated 2020 PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited ("Issuer") The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 ("Subscribers" and each a "Subscriber") INTRODUCTION The parties wish to amend and restate the Notes Subscription Agreement as set out in this deed. COVENANTS 1. INTERPRETATION 1.1 Definitions: In this deed: "Notes Subscription Agreement" means the notes subscription agreement dated 7 December 2011 (as amended and restated on 4 June 2015) between the Issuer and the Subscribers. "Effective Date" means the date notified by the Issuer as the Effective Date in accordance with clause 2.1. 1.2 Notes Subscription Agreement definitions: Words and expressions defined in the Notes Subscription Agreement (as amended by this deed) have, except to the extent the context requires otherwise, the same meaning in this deed. 1.3 Miscellaneous: (a) Headings are inserted for convenience only and do not affect interpretation of this deed. (b) References to a person include that person's successors, permitted assigns, executors and administrators (as applicable). (c) Unless the context otherwise requires, the singular includes the plural and vice versa and words denoting individuals include other persons and vice versa. (d) A reference to any legislation includes any statutory regulations, rules, orders or instruments made or issued pursuant to that legislation and any amendment to, re- enactment of, or replacement of, that legislation. (e) A reference to any document includes reference to that document as amended, modified, novated, supplemented, varied or replaced from time to time. -

HRE05002-038.Pdf(PDF, 152

Appendix S: Parties Notified List of tables Table S1: Government departments and Crown agencies notified ........................... 837 Table S2: Interested parties notified .......................................................................... 840 Table S3: Interested Māori parties ............................................................................ 847 Table S1: Government departments and Crown agencies notified Job Title Organisation City Manager Biosecurity Greater Wellington - The Regional Council Masterton 5915 Environment Health Officer Wairoa District Council Wairoa 4192 Ministry of Research, Science & Wellington 6015 Technology (MoRST) Manager, Animal Containment AgResearch Limited Hamilton 2001 Facility Group Manager, Legal AgResearch Limited Hamilton Policy Analyst Human Rights Commission Auckland 1036 Management, Monitoring & Ministry of Pacific Island Affairs Wellington 6015 Governance Fish & Game Council of New Zealand Wellington 6032 Engineer Land Transport Safety Authority Wellington 6015 Senior Fisheries Officer Fish & Game Eastern Region Rotorua 3220 Adviser Ministry of Research, Science & Wellington 6015 Technology (MoRST) Programme Manager Environment Waikato Hamilton 2032 Biosecurity Manager Environment Southland Invercargill 9520 Dean of Science and University of Waikato Hamilton 3240 Technology Director National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Wellington 6041 Research Limited (NIWA) Chief Executive Officer Horticulture and Food Research Institute Auckland 1020 (HortResearch Auckland) Team Leader Regulatory -

The Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve

The Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve and light pollution issues in New Zealand John Hearnshaw Emeritus professor of astronomy University of Canterbury, New Zealand IAU General Assembly, Honolulu, 12 August 2015 Professor John Hearnshaw University of Canterbury, IAU GA Honolulu, 12 August 2015 Honolulu, 12 IAU GA Professor John Hearnshaw University of Canterbury, The Mackenzie District Lighting Ordinance 1981 Lighting Ordinance drawn up in Mackenzie District Plan. Enacted through Town & Country Planning Act 1977. Controls outdoor lighting (types of light, full cut-off, limits emission below 440 nm, restricts times when outdoor recreational illumination is permitted). The objective of the ordinance is: ‘Maintenance of the ability to undertake effective research at the Mt John University Observatory and of the ability to view the quality of the night sky’. Professor John Hearnshaw University of Canterbury, IAU GA Honolulu, 12 August 2015 Honolulu, 12 IAU GA Professor John Hearnshaw University of Canterbury, Area of the lighting ordinance The lighting ordinance applies over a large area of the Mackenzie Basin, including all of Lakes Tekapo and Pukaki. Area ~ 60 km EW; ~ 100 km NS. 25 km Professor John Hearnshaw University of Canterbury, IAU GA Honolulu, 12 August 2015 Honolulu, 12 IAU GA Professor John Hearnshaw University of Canterbury, Where are we? Mt John and Tekapo from space MJUO Professor John Hearnshaw University of Canterbury, IAU GA Honolulu, 12 August 2015 Honolulu, 12 IAU GA Professor John Hearnshaw University of Canterbury, Light pollution as seen from space The light recorded in these satellite images represents light going up into space. It is wasted light and wasted energy. -

To the Mayor and Councillors of the Mackenzie District Council

1 TH 435 MEETING OF THE MACKENZIE DISTRICT COUNCIL TO THE MAYOR AND COUNCILLORS OF THE MACKENZIE DISTRICT COUNCIL Membership of the Council: Claire Barlow (Mayor) Cr Russell Armstrong Cr Murray Cox Cr Noel Jackson Cr James Leslie Cr Graham Smith Cr Evan Williams Notice is given of a meeting of the Mackenzie District Council to be held on Tuesday June 10, 2014, at 10am, to consider submissions to the 2014/15 Draft Annual Plan, to be followed by a meeting of the Mackenzie District Council to adopt the 2014/15 Annual Plan. VENUE: Council Chambers, Fairlie BUSINESS: To consider submissions to, and then adopt the 2014/15 Draft Annual Plan. WAYNE BARNETT CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 2 MACKENZIE DISTRICT COUNCIL REPORT TO: MACKENZIE DISTRICT COUNCIL FROM: CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER SUBJECT: HEARING OF SUBMISSIONS TO THE ANNUAL PLAN 2014/2015 MEETING DATE: 10 JUNE 2014 REF: PAD 10/3/1 PURPOSE OF REPORT: To provide information for the hearing submissions to the Annual Plan 2014/2015: Submission hearing timetable. List of submissions received. A copy of all submissions received. STAFF RECOMMENDATIONS: 1. That the report be received. 2. That the submissions for the Annual Plan 2014/2015 be considered. WAYNE BARNETT CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 3 List of Submissions Submission Page Name of Submitter Number Number Keith Turner, Community and Public Health 1 5 Alasdair Chapman, Twizel 2 6 Colin McNeilly, Mosgiel 3 7 Phil Keene, NZ Landcare Trust 4 8 Mitch Taylor, Mackenzie Rugby Football Club 5 11 Julie Greig/Jan Zyzalo, Burkes Pass 6 12 Peter Maxwell, Lake -

Public Notice of Proposed Change 13 (Rural Zone- Mackenzie Basin) to the Mackenzie District Plan

Public Notice of Proposed Change 13 (Rural Zone- Mackenzie Basin) to the Mackenzie District Plan Clause 5 of the First Schedule of the Resource Management Act 1991 The Mackenzie District Council has prepared Proposed Plan Change 13 Rural Zone- Mackenzie Basin to the Mackenzie District Plan. The primary purpose of this Plan Change is to provide greater protection of the landscape values of the Mackenzie Basin from inappropriate subdivision, development and use. To achieve this greater acknowledgement of outstanding natural landscapes and features within the District is provided through objectives, policies and rules, particular as they apply to the Mackenzie Basin. A new rural residential zone is created for the Manuka Terrace area that lies between the Ohau Canal and Lake Ohau, which recognises recent subdivision of this area into large residential lots. The Plan Change also addresses a number of minor matters and errors and omissions in the subdivision and transportation rules including a limitation on the number of lots that can be served by private rights-of-way and the method of calculating reserve contribution credits. The main provisions of this Change are set out below: Rural Issues, Objectives and Policies Split existing Objective 3 Landscape Values into Objective 3A, which focuses on outstanding natural landscapes, and Objective 3B, which deals with general landscape values across the District. New policies to support Objective 3A with residential use and subdivision generally being limited to either existing towns or existing clusters of building usually associated with homesteads. Provision is also made for the establishment of new clusters where they meet stringent standards and have the ability to replicate existing clusters or nodes. -

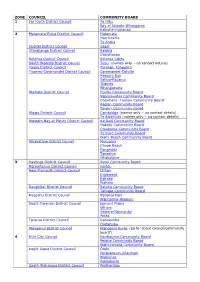

CB List by Zone and Council

ZONE COUNCIL COMMUNITY BOARD 1 Far North District Council Te Hiku Bay of Islands-Whangaroa Kaikohe-Hokianga 2 Matamata-Piako District Council Matamata Morrinsville Te Aroha Opotiki District Council Coast Otorohanga District Council Kawhia Otorohanga Rotorua District Council Rotorua Lakes South Waikato District Council Tirau (names only – no contact details) Taupo District Council Turangi- Tongariro Thames-Coromandel District Council Coromandel-Colville Mercury Bay Tairua-Pauanui Thames Whangamata Waikato District Council Huntly Community Board Ngaruawahia Community Board Onewhero -Tuakau Community Board Raglan Community Board Taupiri Community Board Waipa District Council Cambridge (names only – no contact details) Te Awamutu (names only – no contact details) Western Bay of Plenty District Council Katikati Community Board Maketu Community Board Omokoroa Community Board Te Puke Community Board Waihi Beach Community Board Whakatane District Council Murupara Ohope Beach Rangitaiki Taneatua Whakatane 3 Hastings District Council Rural Community Board Horowhenua District Council Foxton New Plymouth District Council Clifton Inglewood Kaitake Waitara Rangitikei District Council Ratana Community Board Taihape Community Board Ruapehu District Council National Park Waimarino-Waiouru South Taranaki District Council Egmont Plains Eltham Hawera-Normanby Patea Tararua District Council Dannevirke Eketahuna Wanganui District Council Wanganui Rural (go to ‘about council/community board’) 4 Hutt City Council Eastbourne Community Board Petone Community Board -

Mackenzie District Tekapo Traffic Plan Purpose

Mackenzie District Tekapo Traffic Plan Purpose To support the Council with the development of concept designs to address the traffic related challenges being faced. - Significant growth - Increasing domestic and international tourism destination - Residential development Tekapo Progress| March 2018 Area Hot Springs Sign Hamilton Drive Residential Zoning Boundary Tekapo Progress| March 2018 Strategic Objectives • To enhance the mobility of residents and visitors • To increase the safety for all users • To ensure parking is efficient and effective • To enhance legibility to improve wayfinding • To maintain permeable and accessible networks • To enhance sustainability and minimise the impact of transport Tekapo Progress| March 2018 Strategic Issues Average Daily Traffic Volume (vpd) New Year New Christmas/ JAN JAN 2002 2015 JAN JAN Day Waitangi FEB FEB MAR MAR MAR MAR SH8 – APR Easter TrafficFlows APR - MAY Tekapo MAY MAY MAY 2016 Volumes Traffic JUN of Township) (East JUN JUN JUL JUL AUG AUG 2017 AUG SEP SEP SEP OCT OCT OCT Tekapo Progress| MarchProgress| 2018 Tekapo NOV NOV NOV Year New Christmas/ DEC DEC DEC 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 8000 Transport environment - Safety Crash history Tekapo Progress| March 2018 Transport environment – Pedestrian movement 84 152 75 79 63 71 60 Tekapo Progress| March 2018 Parking pressures Tekapo Progress| March 2018 Key challenges • Parking demand • Planning pressures • Church of the Good Shepherd • State Highway 8 Tekapo Progress| March 2018 Parking demand January 2017 – 415 parks Tekapo Parking Occupancy 415 100% 374 90% Peak demand – 245 vehicles 332 80% 291 70% Average total daily - ~1,800 249 60% 208 50% 166 40% 125 30% Parking Occupancy(%) 83 20% 42 10% Numberof Parking Spaces Occupied 0 0% 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 13:00 13:30 14:00 14:30 15:00 15:30 16:00 16:30 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 Period Starting Time Zone 1 Zone 2 Zone 3 Zone 4 Zone 5 Temporary Parking Areas . -

Three Waters

FOR DECISION MŌ TE WHAKATAUNGA TO Mayor and Councillors AUTHOR Adrian de Laborde Group Manager Engineering Services FILE REFERENCE Document: 2807302 Appendix A: Three Waters Reform Programme M2807311 Appendix B: 3 Waters Stimulus Funding Agreement M2807309 Appendix C: Simpson Grierson Advice SOLGM on MOU M2807308 Appendix D: Notional Funding Allocations M2807307 Appendix E: Eater Stimulus Delivery Plan M2807305 Appendix F: Grant Funding Guidance M2807248 PORTFOLIO HOLDER/S Councillor Ross Harris 3 Waters portfolio MEETING DATE 12 August 2020 SUBJECT Department of Internal Affairs 3-Waters Review Memorandum of Understanding SUMMARY | TE WHAKARĀPOPOTANGA This report provides an update on the Governments reform programme for 3 Waters and seeks approval for the Council to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding with the Crown. The decision is not considered to be a significant decision. Whaarangi 1 | 8 M 2807302 RECOMMENDATION | TE WHAIKUPU THAT the report be received. THAT the Council agrees to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding with the Crown, thus agreeing to participate in the initial stage of a central/local government three waters service delivery reform programme THAT the Council authorise the Chief Executive to enter into the Funding Agreement, to accept a grant from the Crown to spend on operating and/or capital expenditure relating to three waters infrastructure and service delivery THAT the Council considers these decisions to be insignificant under its Significance and Engagement Policy 2017. THAT the Council informs the community that the Memorandum of Understanding has been entered into. 1 PURPOSE | TE ARONGA This report provides an update to the Council on the Government’s progress on the reform of 3-Waters. -

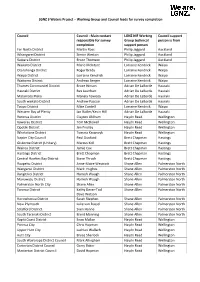

LGNZ 3 Waters Working Group and Council Leads for Survey Completion

LGNZ 3 Waters Project – Working Group and Council leads for survey completion Council Council - Main contact LGNZ NIF Working Council support responsible for survey Group technical person is from completion support person Far North District Martin Ross Philip Jaggard Auckland Whangarei District Simon Weston Philip Jaggard Auckland Kaipara District Bruce Thomson Philip Jaggard Auckland Waikato District Marie McIntyre Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Otorohanga District Roger Brady Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Waipa District Lorraine Kendrick Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Waitomo District Andreas Senger Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Thames Coromandel District Bruce Hinson Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Hauraki District Rex Leonhart Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Matamata Piako Manaia Tewiata Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki South waikato District Andrew Pascoe Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Taupo District Mike Cordell Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Western Bay of Plenty Ian Butler/Kevin Hill Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Rotorua District Clayton Oldham Haydn Read Wellington Kawerau District Tom McDowell Haydn Read Wellington Opotiki District Jim Findlay Haydn Read Wellington Whakatane District Tomasz Krawczyk Haydn Read Wellington Napier City Council Paul Dunford Brett Chapman Hastings Gisborne District (Unitary) Marcus Koll Brett Chapman Hastings Wairoa District Jamie Cox Brett Chapman Hastings Hastings District Brett Chapman Brett Chapman Hastings Central Hawkes Bay District Steve Thrush Brett Chapman Hastings Ruapehu District Anne-Maire Westcott Shane Allen Palmerston North Wanganui District -

To the Mayor and Councillors of the Mackenzie District Council

1 PAD 3/1 425th MEETING OF THE MACKENZIE DISTRICT COUNCIL TO THE MAYOR AND COUNCILLORS OF THE MACKENZIE DISTRICT COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP OF THE COUNCIL Claire Barlow (Mayor) John Bishop Peter Maxwell Annette Money Graeme Page Graham Smith Evan Williams Notice is given of the meeting of the Mackenzie District Council to be held on Tuesday 14 May 2013 at 9.30 am VENUE: Council Chambers, Fairlie BUSINESS: As per Agenda attached. WAYNE BARNETT CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 7 May 2013 O:\Rosemary\2013\Agendas 2013\MDC\14 May 2013\aNotice.doc 2 AGENDA FOR TUESDAY 14 MAY 2013 I. OPENING II. APOLOGIES III. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST IV. BEREAVEMENTS V. MAYORAL REPORT VI. REPORTS REQUIRING COUNCIL DECISIONS 1. Cemeteries and Pensioner Housing Fees and Charges 2. Regulatory Fees and Charges 3. Speed Limit Bylaw 4. Architect’s Fees for Twizel Toilets (1 further attachment to be circulated separately) 5. New Elected Member Remuneration Model VII. INFORMATION REPORTS 1. Chief Executive Officer’s Activities 2. Christchurch Canterbury Tourism Report 3. Local Government Acts: Ministerial Powers of Intervention VIII. COMMUNITY BOARDS IX. COMMITTEES Receive the Minutes of the Meetings of the Mackenzie Forestry Board, Finance Committee, Projects and Strategies Committee and Planning Committee held on 23 April 2013 including such parts as were taken with the Public Excluded. X. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES Confirm and adopt the Minutes of the Mackenzie District Council Meeting held held on 2 April 2013 including such parts as were taken with the Public Excluded ACTION POINTS XI PUBLIC EXCLUDED That the public be excluded from the following part of the proceedings of this meeting namely: 1.