THE DRUM MAJOR Class of 2019 Essay Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

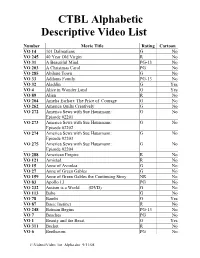

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List Number Movie Title Rating Cartoon VO 14 101 Dalmatians G No VO 245 40 Year Old Virgin R No VO 31 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 No VO 203 A Christmas Carol PG No VO 285 Abilene Town G No VO 33 Addams Family PG-13 No VO 32 Aladdin G Yes VO 4 Alice in Wonder Land G Yes VO 89 Alien R No VO 204 Amelia Earhart: The Price of Courage G No VO 262 America Quilts Creatively G No VO 272 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2201 VO 273 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2202 VO 274 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2203 VO 275 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2204 VO 288 American Empire R No VO 121 Amistad R No VO 15 Anne of Avonlea G No VO 27 Anne of Green Gables G No VO 159 Anne of Green Gables the Continuing Story NR No VO 83 Apollo 13 PG No VO 232 Autism is a World (DVD) G No VO 113 Babe G No VO 78 Bambi G Yes VO 87 Basic Instinct R No VO 248 Batman Begins PG-13 No VO 7 Beaches PG No VO 1 Beauty and the Beast G Yes VO 311 Becket R No VO 6 Beethoven PG No J:\Videos\Video_list_Alpha.doc 9/11/08 VO 160 Bells of St. Mary’s NR No VO 20 Beverly Hills Cop R No VO 79 Big PG No VO 163 Big Bear NR No VO 289 Blackbeard, The Pirate R No VO 118 Blue Hawaii NR No VO 290 Border Cop R No VO 63 Breakfast at Tiffany's NR No VO 180 Bridget Jones’ Diary R No VO 183 Broadcast News R No VO 254 Brokeback Mountain R No VO 199 Bruce Almighty Pg-13 No VO 77 Butch Cassidy and the Sun Dance Kid PG No VO 158 Bye Bye Blues PG No VO 164 Call of the Wild PG No VO 291 Captain Kidd R No VO 94 Casablanca -

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven Limited Edition Blu-ray release (2-disc set) on 2 December 2019 From legendary filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Basic Instinct) and screenwriter Gerard Soeteman (Soldier of Orange) comes an explosive, fast-paced and thrilling coming- of-age drama. Raw, intense and unabashedly sexual, Spetters is a wild ride that will knock the unsuspecting for a loop. Starring Renée Soutendijk, Jeroen Krabbé (The Fugitive) and the late great Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner), this limited edition 2-disc set (1 x Blu-ray & 1 x DVD) brings Spetters to Blu-ray for the first time in the UK and is a must own release, packed with over 4 hours of bonus content. In Spetters, three friends long for better lives and see their love of motorcycle racing as a perfect way of doing it. However the arrival of the beautiful and ambitious Fientje threatens to come between them. Special features Remastered in 4K and presented in High Definition for the first time in the UK Audio commentary by director Paul Verhoeven Symbolic Power, Profit and Performance in Paul Verhoeven’s Spetters (2019, 17 mins): audiovisual essay written and narrated by Amy Simmons Andere Tijden: Spetters (2002, 29 mins): Dutch TV documentary on the making of Spetters, featuring the filmmakers, cast and critics of the film Speed Crazy: An Interview with Paul Verhoeven (2014, 8 mins) Writing Spetters: An Interview with Gerard Soeteman (2014, 11 mins) An Interview with Jost Vacano (2014, 67 mins): wide ranging interview with the film’s cinematographer discussing his work on films including Soldier of Orange and Robocop Image gallery Trailers Illustrated booklet (***first pressing only***) containing a new interview with Paul Verhoeven by the BFI’s Peter Stanley, essays by Gerard Soeteman, Rob van Scheers and Peter Verstraten, a contemporary review, notes on the extras and film credits Product details RRP: £22.99 / Cat. -

Showgirls Comes of Age

SHOWGIRLS COMES OF AGE PHIL HOBBINS-WHITE POPMEC RESEARCH BLOG Showgirls, Paul Verhoeven’s much-maligned erotic film celebrates its twenty-fifth an- niversary later this year. This essay seeks to re-assess the film—which was almost uni- versally derided upon its release in 1995—now that it is a quarter of a century old. Telling the story of a drifter who hitches a ride to Las Vegas, Nomi Malone (Elizabeth Berkley) works hard to climb the ladder from stripper to casino showgirl, making a series of acquaintances along the way, many of whom are only looking to exploit her. On the surface, the film seems to be simple, made to satiate the desires of the audi- ence—primarily heterosexual males—however there are arguments to be made that Showgirls is so much more than that. This essay is in two sections: firstly, this part will contextualise the film, acknowledge some of the film’s criticisms, and will then go on to consider the film as a postmodern self-critique. The second instalment will go on to analyse Showgirls as an indictment of America in terms of its hegemonic structures, artificiality, its exploitative nature, and stardom. There is just so much interesting context to Showgirls, including the choices of direc- tor and writer, casting, budget, marketing, Hollywood studios, and the certification of the film. Showgirls is directed by Paul Verhoeven, whose reputation had grown with multiple successes in his native Netherlands before making the successful Hollywood films Robocop (1987) and Total Recall (1990). It was with his 1992 erotic thriller, Basic Instinct, that Verhoeven really became a household name director. -

Telling Lies in America Joe Eszterhas Is a Big-Bucks Screenwriter Who

Telling Lies in America Joe Eszterhas is a big-bucks screenwriter who earned millions for slick trash (like Flashdance and Basic Instinct) and total trash (Jade, Showgirls) but who now has returned to his roots with his latest script. Very different from his previous efforts is Telling Lies to America , a coming of age story about a Hungarian immigrant kid growing up poor and ambitious in Cleveland (Eszterhas’ hometown), in the early 1960’s era of burgeoning rock n’ roll. The kid is teenager Karchy Jonas (Brad Renfro), an outsider at his high school who still has trouble pronouncing that tough “th” of English and who has to work nights at an egg plant to help support his factory worker father (Maximilian Schell). Karchy has an inchoate desire for a better life and grabs his chance when a local celebrity, slick disc jockey Billy Magic (Kevin Bacon) takes him on as a go-fer. Billy, willing to plug teenybopper tunes for dough, really loves rhythm and blues (what he calls “sweaty collars and dirty fingernails music”), and he humors Karchy because he recognizes his own deceitful youth in the lad. In a new cool jacket, Karchy dreams of being a dj himself, complete with the girls, the hot car, and the flash he sees Billy possesses. His newfound hustle, however, loses him the respect of his old-country father and his co-worker and girlfriend Diney (Calista Flockhart), and, when he gets mired in Billy’s payola schemes as a material witness for government investigators, he learns the price of prevaricating to get ahead. -

Quantitative Dynamics of Human Empires

Quantitative Dynamics of Human Empires Cesare Marchetti and Jesse H. Ausubel FOREWORD Humans are territorial animals, and most wars are squabbles over territory. become global. And, incidentally, once a month they have their top managers A basic territorial instinct is imprinted in the limbic brain—or our “snake meet somewhere to refresh the hierarchy, although the formal motives are brain” as it is sometimes dubbed. This basic instinct is central to our daily life. to coordinate business and exchange experiences. The political machinery is Only external constraints can limit the greedy desire to bring more territory more viscous, and we may have to wait a couple more generations to see a under control. With the encouragement of Andrew Marshall, we thought it global empire. might be instructive to dig into the mechanisms of territoriality and their role The fact that the growth of an empire follows a single logistic equation in human history and the future. for hundreds of years suggests that the whole process is under the control In this report, we analyze twenty extreme examples of territoriality, of automatic mechanisms, much more than the whims of Genghis Khan namely empires. The empires grow logistically with time constants of tens to or Napoleon. The intuitions of Menenius Agrippa in ancient Rome and of hundreds of years, following a single equation. We discovered that the size of Thomas Hobbes in his Leviathan may, after all, be scientifically true. empires corresponds to a couple of weeks of travel from the capital to the rim We are grateful to Prof. Brunetto Chiarelli for encouraging publication using the fastest transportation system available. -

Table of Contents

The Nineties in America Table of Contents A Abortion Academy Awards Advertising Africa and the United States African Americans Agassi, Andre Agriculture in Canada Agriculture in the United States AIDS epidemic Air pollution Airline industry Albee, Edward Albert, Marv Albright, Madeleine Allen, Woody Ally McBeal Alternative rock Alvarez, Julia Alzheimer's disease Amazon.com America Online Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 AmeriCorps Angelou, Maya Angels in America Antidepressants Apple Computer Archaeology Archer Daniels Midland scandal Architecture Armey, Dick Armstrong, Lance Arnett, Peter Art movements Asian Americans Astronomy Attention-deficit disorder Audiobooks Autism Auto racing Automobile industry B Bailey, Donovan Baker, James Baker v. Vermont Balanced Budget Act of 1997 Ballet Bank mergers Barkley, Charles Barry, Dave Barry, Marion Baseball Baseball realignment Baseball strike of 1994 Basic Instinct Basketball Baywatch Beanie Babies Beauty and the Beast Beauty Myth, The Beavis and Butt-Head Bernadin, Joseph Cardinal Beverly Hills, 90210 Bezos, Jeff Biosphere 2 Blair, Bonnie Blair Witch Project, The Blended families Bloc Québécois Blogs Bobbitt mutilation case Bondar, Roberta Bono, Sonny Book clubs Bosnia conflict Bowl Championship Series (BCS) Boxing Boy bands Broadway musicals Brooks, Garth Brown, Ron Browning, Kurt Buchanan, Pat Buffett, Warren Burning Man festivals Bush, George H. W. Business and the economy in Canada Business and the economy in the United States Byrd murder case C Cable television Cammermeyer, Margarethe -

A Subcategory of Neo Noir Film Certificate of Original Authorship

Louise Alston Supervisor: Gillian Leahy Co-supervisor: Margot Nash Doctorate in Creative Arts University of Technology Sydney Femme noir: a subcategory of neo noir film Certificate of Original Authorship I, Louise Alston, declare that this thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Doctorate of Creative Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Technology Sydney. This thesis is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the exegesis. This document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. This research is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program. Signature: Production Note: Signature removed prior to publication. Date: 05.09.2019 2 Acknowledgements Feedback and support for this thesis has been provided by my supervisor Dr Gillian Leahy with contributions by Dr Alex Munt, Dr Tara Forrest and Dr Margot Nash. Copy editing services provided by Emma Wise. Support and feedback for my creative work has come from my partner Stephen Vagg and my screenwriting group. Thanks go to the UTS librarians, especially those who generously and anonymously responded to my enquiries on the UTS Library online ‘ask a librarian’ service. This thesis is dedicated to my daughter Kathleen, who joined in half way through. 3 Format This thesis is composed of two parts: Part one is my creative project. It is an adaptation of Frank Wedekind’s Lulu plays in the form of a contemporary neo noir screenplay. Part two is my exegesis in which I answer my thesis question. -

1-Abdul Haseeb Ansari

Journal of Criminal Justice and Law Review : Vol. 1 • No. 1 • June 2009 IDENTIFYING LARGE REPLICABLE FILM POPULATIONS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE FILM RESEARCH: A UNIFIED FILM POPULATION IDENTIFICATION METHODOLOGY FRANKLIN T. WILSON Indiana State University ABSTRACT: Historically, a dominant proportion of academic studies of social science issues in theatrically released films have focused on issues surrounding crime and the criminal justice system. Additionally, a dominant proportion has utilized non-probability sampling methods in identifying the films to be analyzed. Arguably one of the primary reasons film studies of social science issues have used non-probability samples may be that no one has established definitive operational definitions of populations of films, let alone develop datasets from which researchers can draw. In this article a new methodology for establishing film populations for both qualitative and quantitative research–the Unified Film Population Identification Methodology–is both described and demonstrated. This methodology was created and is presented here in hopes of expand the types of film studies utilized in the examination of social science issues to those communication theories that require the examination of large blocks of media. Further, it is anticipated that this methodology will help unify film studies of social science issues in the future and, as a result, increase the reliability, validity, and replicability of the said studies. Keywords: UFPIM, Film, Core Cop, Methodology, probability. Mass media research conducted in the academic realm has generally been theoretical in nature, utilizing public data, with research agendas emanating from the academic researchers themselves. Academic studies cover a gambit of areas including, but not limited to, antisocial and prosocial effects of specific media content, uses and gratifications, agenda setting by the media, and the cultivation of perceptions of social reality (Wimmer & Dominick, 2003). -

Drama Movies

Libraries DRAMA MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 42 DVD-5254 12 DVD-1200 70's DVD-0418 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 8 1/2 DVD-3832 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 127 Hours DVD-8008 8 Mile DVD-1639 1776 DVD-0397 9th Company DVD-1383 1900 DVD-4443 About Schmidt DVD-9630 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Accused DVD-6182 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 1 Ace in the Hole DVD-9473 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1 Across the Universe DVD-5997 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adam Bede DVD-7149 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adjustment Bureau DVD-9591 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs 1 Admiral DVD-7558 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs 5 Adventures of Don Juan DVD-2916 25th Hour DVD-2291 Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert DVD-4365 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 Advise and Consent DVD-1514 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 Affair to Remember DVD-1201 3 Women DVD-4850 After Hours DVD-3053 35 Shots of Rum c.2 DVD-4729 c.2 Against All Odds DVD-8241 400 Blows DVD-0336 Age of Consent (Michael Powell) DVD-4779 DVD-8362 Age of Innocence DVD-6179 8/30/2019 Age of Innocence c.2 DVD-6179 c.2 All the King's Men DVD-3291 Agony and the Ecstasy DVD-3308 DVD-9634 Aguirre: The Wrath of God DVD-4816 All the Mornings of the World DVD-1274 Aladin (Bollywood) DVD-6178 All the President's Men DVD-8371 Alexander Nevsky DVD-4983 Amadeus DVD-0099 Alfie DVD-9492 Amar Akbar Anthony DVD-5078 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Amarcord DVD-4426 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul c.2 DVD-4725 c.2 Amazing Dr. -

"Rollerball" Dystopian Movie: Fictional Generative Themes to Stimulate Sociological Imagination Within Physical Education and Sports Studies Movimento, Vol

Movimento ISSN: 0104-754X [email protected] Escola de Educação Física Brasil Barbero-González, José-Ignacio; Rodríguez-Campazas, Hugo The near future in "rollerball" dystopian movie: fictional generative themes to stimulate sociological imagination within Physical Education and sports studies Movimento, vol. 19, núm. 3, julio-septiembre, 2013, pp. 79-101 Escola de Educação Física Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=115328026001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative The near future in "rollerball" dystopian movie: fictional generative themes to stimulate sociological imagination within Physical Education and sports studies José-Ignacio Barbero-González* Hugo Rodríguez-Campazas** Abstract: Cinema is a powerful device of public pedagogy whose potential is to a great extent neglected by the educational system. In this context, this paper illustrates how sport-related films (Rollerball) may be used pedagogically to stimulate the exercise of the sociological imagination within PE/Sports studies. To do so, we focus on a few concept/ images with generative power to encourage a dialogical approach to a bunch of significant topics related to culture, ideology, pedagogy and sport. Our underlying premise is that nontraditional texts constitute a useful tool -

The Violent Juvenile Offender: an Empirical Portrait

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. L m II LN/ E // Pro@@@@@@ @ss~es •Edited by: Robert A. Mathias 9s@ Degu~S® I 22.... " " NCJ#() ~_5-14 ~---- .o. hlan from: 0 ? y-/~ / National Criminal Justice Reference Service Research and Information Center NAME: ~/~ ~~~ ~ DATE: ~y / t. Please return to the National llnstitule of Justice Library wi|h lhis sllp. To renew past the due date, call NCJRS at (301)251-5063. VIOLENT JUVENILE OFFENDERS An Anthology VIOLENT JUVENILE OFFENDERS An Anthology Edited by: Robert A. Mathias Patti DeMuro Richard S. Allinson Violent Juvenile Offenders,An Anthology NATIONALCOUNCIL ON CRIME AND DELINQUENCY 760 Market Street, Suite 433 • San Francisco, California 94102 415/956-5661 Copyright ©1984 by the National Council on Crime and Delinquency Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 84-60252 Graphic design by E. Fitz Art, Hackensack, NJ This book was prepared under Cooperative Agreement 80-MU-AX- K008 awarded to the National Council on Crime and Delinquency by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view or opinions expressed in this book are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the U.S. Department of Justice or the National Council on Crime and Delinquency. CONTENTS Foreword ................................................ XIII Introduction .............................................. XV Part One EXTENT AND CAUSES OF VIOLENT JUVENILE CRIME Chapter 1 Recent National Trends in Serious Juvenile Crime ........................ 5 Paul A. Strasburg Data Sources and Definitions ............................. 6 Broad Trends in Youth Violence ........................... 8 Patterns of Offending ................................... 12 Victims of Juvenile Violence .............................