Naughty Bits February 2019 SUBMISSION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

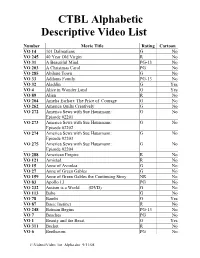

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List Number Movie Title Rating Cartoon VO 14 101 Dalmatians G No VO 245 40 Year Old Virgin R No VO 31 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 No VO 203 A Christmas Carol PG No VO 285 Abilene Town G No VO 33 Addams Family PG-13 No VO 32 Aladdin G Yes VO 4 Alice in Wonder Land G Yes VO 89 Alien R No VO 204 Amelia Earhart: The Price of Courage G No VO 262 America Quilts Creatively G No VO 272 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2201 VO 273 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2202 VO 274 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2203 VO 275 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2204 VO 288 American Empire R No VO 121 Amistad R No VO 15 Anne of Avonlea G No VO 27 Anne of Green Gables G No VO 159 Anne of Green Gables the Continuing Story NR No VO 83 Apollo 13 PG No VO 232 Autism is a World (DVD) G No VO 113 Babe G No VO 78 Bambi G Yes VO 87 Basic Instinct R No VO 248 Batman Begins PG-13 No VO 7 Beaches PG No VO 1 Beauty and the Beast G Yes VO 311 Becket R No VO 6 Beethoven PG No J:\Videos\Video_list_Alpha.doc 9/11/08 VO 160 Bells of St. Mary’s NR No VO 20 Beverly Hills Cop R No VO 79 Big PG No VO 163 Big Bear NR No VO 289 Blackbeard, The Pirate R No VO 118 Blue Hawaii NR No VO 290 Border Cop R No VO 63 Breakfast at Tiffany's NR No VO 180 Bridget Jones’ Diary R No VO 183 Broadcast News R No VO 254 Brokeback Mountain R No VO 199 Bruce Almighty Pg-13 No VO 77 Butch Cassidy and the Sun Dance Kid PG No VO 158 Bye Bye Blues PG No VO 164 Call of the Wild PG No VO 291 Captain Kidd R No VO 94 Casablanca -

No. 16-56843 UNITED STATES COURT OF

Case: 16-56843, 02/22/2017, ID: 10330044, DktEntry: 74, Page 1 of 36 No. 16-56843 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT VIDANGEL, INC., Defendant-Appellant, v. DISNEY ENTERPRISES, INC.; LUCASFILM LTD. LLC; TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION; AND WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT, INC., Plaintiffs-Appellees. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Hon. André Birotte Jr. No. 2:16-cv-04109-AB-PLA APPELLANT’S REPLY BRIEF Brendan S. Maher Peter K. Stris Daniel L. Geyser Elizabeth Rogers Brannen Douglas D. Geyser Dana Berkowitz STRIS & MAHER LLP Victor O’Connell 6688 N. Central Expy., Ste. 1650 STRIS & MAHER LLP Dallas, TX 75206 725 S. Figueroa St., Ste. 1830 Telephone: (214) 396-6630 Los Angeles, CA 90017 Facsimile: (210) 978-5430 Telephone: (213) 995-6800 Facsimile: (213) 261-0299 February 22, 2017 [email protected] Counsel for Defendant-Appellant VidAngel, Inc. (Additional counsel on signature page) 175603.6 182634.2 Case: 16-56843, 02/22/2017, ID: 10330044, DktEntry: 74, Page 2 of 36 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1 ARGUMENT .............................................................................................................3 I. The Studios’ Narrative Is Misleading .............................................................. 3 A. VidAngel’s Business Is -

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven Limited Edition Blu-ray release (2-disc set) on 2 December 2019 From legendary filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Basic Instinct) and screenwriter Gerard Soeteman (Soldier of Orange) comes an explosive, fast-paced and thrilling coming- of-age drama. Raw, intense and unabashedly sexual, Spetters is a wild ride that will knock the unsuspecting for a loop. Starring Renée Soutendijk, Jeroen Krabbé (The Fugitive) and the late great Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner), this limited edition 2-disc set (1 x Blu-ray & 1 x DVD) brings Spetters to Blu-ray for the first time in the UK and is a must own release, packed with over 4 hours of bonus content. In Spetters, three friends long for better lives and see their love of motorcycle racing as a perfect way of doing it. However the arrival of the beautiful and ambitious Fientje threatens to come between them. Special features Remastered in 4K and presented in High Definition for the first time in the UK Audio commentary by director Paul Verhoeven Symbolic Power, Profit and Performance in Paul Verhoeven’s Spetters (2019, 17 mins): audiovisual essay written and narrated by Amy Simmons Andere Tijden: Spetters (2002, 29 mins): Dutch TV documentary on the making of Spetters, featuring the filmmakers, cast and critics of the film Speed Crazy: An Interview with Paul Verhoeven (2014, 8 mins) Writing Spetters: An Interview with Gerard Soeteman (2014, 11 mins) An Interview with Jost Vacano (2014, 67 mins): wide ranging interview with the film’s cinematographer discussing his work on films including Soldier of Orange and Robocop Image gallery Trailers Illustrated booklet (***first pressing only***) containing a new interview with Paul Verhoeven by the BFI’s Peter Stanley, essays by Gerard Soeteman, Rob van Scheers and Peter Verstraten, a contemporary review, notes on the extras and film credits Product details RRP: £22.99 / Cat. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

December 2018 Pg

3000 W. Congress St. Lafayette, LA 70506 Inside This Issue: •Dear Santa pg. 3 • Petlights pg. 8 •Carlights pg. 9 •Candy Cane Review pg. 11 •Last Minute Christmas Gifts pg. 13 LHS Student & Teacher of the Year •Apple’s iPhone Scandal December 2018 pg. 14 •Merry Christmas vs. Happy Holidays Editorial Merry Christmas pg. 15 2 NEWS December 2018 Parlez-Vous Staff Editors Quote of the Month Kaitlyn Daigle “It is Christmas in the heart Hannah Michel that puts Christmas in the air.” - W. T. Ellis Senior Staff Writer Hannah Kuhn Kate Manuel Taylor Lejeune Joke of the Month Liam Jochum What does a snowman call his offspring? Olivia Cart His CHILL-dren! Emma Bearb Hailey Corcoran Junior Staff Writers Maribeth Cowart Questions? Comments? Concerns? Darian Jacob Contact Mrs. Manuel in room 231. Britney Lahocki Alyssa Magnon The LHS mission is to inspire and Sponsor: Mrs. Manuel empower students within a disciplined, aca- demic environment to become ethical, well-rounded contributors to society. Follow @parlezvousnewspaper on Instagram and @ParlezVousNews on Twitter for updates between each month December3 2018 NEWS BRIEFS 3 “I just want buttloads of money,” Kamryn Dear Santa... Eugene, Junior. “Please bring Jennifer Aniston to my door, by Taylor Lejeune immediately,” Maryn Short, Senior. Business Manager “Please don’t let my dog eat the Christmas presents this year,” Mrs. Keller, Teacher. “Can you bump up my ACT score?” Haden “All I want for Christmas is you,” Todd Cormier, Senior. Lejeune, Freshman. “Drop a lil boyfriend under the tree for me,” Anna Sebastian, Senior. “When did you become a math teacher?” “I’m starting to get suspicious about this Kelly Wood, Senior. -

June 17, 2019-0932 Disney RTP.Ecl

960 1 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 2 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA - WESTERN DIVISION 3 HONORABLE ANDRÉ BIROTTE JR., U.S. DISTRICT JUDGE 4 5 DISNEY ENTERPRISES, INC., ET ) AL., ) 6 ) PLAINTIFFS, ) 7 ) vs. ) No. CV 16-4109-AB 8 ) VIDANGEL, INC., ) 9 ) DEFENDANT. ) 10 ________________________________) 11 12 13 REPORTER'S TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS 14 MONDAY, JUNE 17, 2019 15 9:41 A.M. 16 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 17 Day 5 of Jury Trial, Pages 960 through 1064, inclusive 18 19 20 21 22 ____________________________________________________________ 23 CHIA MEI JUI, CSR 3287, CCRR, FCRR FEDERAL OFFICIAL COURT REPORTER 24 350 WEST FIRST STREET, ROOM 4311 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90012 25 [email protected] CHIA MEI JUI, CSR 3287, CRR, FCRR UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT, CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 961 1 APPEARANCES OF COUNSEL: 2 FOR THE PLAINTIFFS: 3 MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP BY: KELLY M. KLAUS, ATTORNEY AT LAW 4 560 MISSION STREET, 27TH FLOOR SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94105 5 (415) 512-4017 (415) 512-4028 6 MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP 7 BY: ROSE LEDA EHLER, ATTORNEY AT LAW AND BLANCA YOUNG, ATTORNEY AT LAW 8 350 SOUTH GRAND AVENUE, 50TH FLOOR LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90071 9 (213) 683-9100 10 11 FOR THE DEFENDANT: 12 CALL & JENSEN BY: SAMUEL G. BROOKS, ATTORNEY AT LAW 13 AND MARK L. EISENHUT, ATTORNEY AT LAW 610 NEWPORT CENTER DRIVE, SUITE 700 14 NEWPORT BEACH, CALIFORNIA 92660 (949) 717-3000 15 VIDANGEL, INC. 16 BY: J. MORGAN PHILPOT, ATTORNEY AT LAW 295 WEST CENTER STREET 17 PROVO, UTAH 84601 (801) 810-8369 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 CHIA MEI JUI, CSR 3287, CRR, FCRR UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT, CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 962 1 LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA; MONDAY, JUNE 17, 2019 2 9:41 A.M. -

'Lifelong Learning' At

Why are drones hovering over the upper school? PHOTO BY PEPE MIRALLES’ DRONE Published biweekly by and for the Upper School students of Riverfield Country Day School in Tulsa, OK MARCHAPRIL 30,3, 2015 2018 THE COMMONS n keeping with the spirit of I April Fools’ Day, material contained in this issue is inten- tionally fraudulent and meant to amuse. Any resemblance to reality is not coincidental. IA drones terrorize ARCHITECTS’ VIEW OF NEW CAMPUS school By Logan Payne COWERING IN FEAR Over the past few weeks, the Riverfield campus has been under attack by drones. The attack has been traced to the Industrial Arts class run by James Wilson and Fredrick Jones. Neither of the teachers is implicated in the terrorist attack. On the contrary, this is the work of one of their students. The mastermind behind the ‘L ifelong learning’ at attack is Altug Delen, well known as a flyer and command- er of drones. Delen’s abilities are so advanced that students tremble in fear at the thought of going outside. The school has been on total lockdown since this rebellion started. Riverfield university At first it appeared to be nothing more than a funny game By James Morley One concern about this new university is whether or not Delen was playing. It turned FUTURE R.U. DROPOUT the school can gather sufficient funds to build and run a fully serious when the entire Industri- functional university on tuition alone. I spoke to Jerry Bates, al Arts class began using the iverfield Country Day School was founded in RCDS Head of School, to see what the plans are. -

Bob Iger Kevin Mayer Michael Paull Randy Freer James Pitaro Russell

APRIL 11, 2019 Disney Speakers: Bob Iger Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Kevin Mayer Chairman, Direct-to-Consumer & International Michael Paull President, Disney Streaming Services Randy Freer Chief Executive Officer, Hulu James Pitaro Co-Chairman, Disney Media Networks Group and President, ESPN Russell Wolff Executive Vice President & General Manager, ESPN+ Uday Shankar President, The Walt Disney Company Asia Pacific and Chairman, Star & Disney India Ricky Strauss President, Content & Marketing, Disney+ Jennifer Lee Chief Creative Officer, Walt Disney Animation Studios ©Disney Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 Disney Speakers (continued): Pete Docter Chief Creative Officer, Pixar Kevin Feige President, Marvel Studios Kathleen Kennedy President, Lucasfilm Sean Bailey President, Walt Disney Studios Motion Picture Productions Courteney Monroe President, National Geographic Global Television Networks Gary Marsh President & Chief Creative Officer, Disney Channel Agnes Chu Senior Vice President of Content, Disney+ Christine McCarthy Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Lowell Singer Senior Vice President, Investor Relations Page 2 Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 PRESENTATION Lowell Singer – Senior Vice President, Investor Relations, The Walt Disney Company Good afternoon. I'm Lowell Singer, Senior Vice President of Investor Relations at THe Walt Disney Company, and it's my pleasure to welcome you to the webcast of our Disney Investor Day 2019. Over the past 1.5 years, you've Had many questions about our direct-to-consumer strategy and services. And our goal today is to answer as many of them as possible. So let me provide some details for the day. Disney's CHairman and CHief Executive Officer, Bob Iger, will start us off. -

Showgirls Comes of Age

SHOWGIRLS COMES OF AGE PHIL HOBBINS-WHITE POPMEC RESEARCH BLOG Showgirls, Paul Verhoeven’s much-maligned erotic film celebrates its twenty-fifth an- niversary later this year. This essay seeks to re-assess the film—which was almost uni- versally derided upon its release in 1995—now that it is a quarter of a century old. Telling the story of a drifter who hitches a ride to Las Vegas, Nomi Malone (Elizabeth Berkley) works hard to climb the ladder from stripper to casino showgirl, making a series of acquaintances along the way, many of whom are only looking to exploit her. On the surface, the film seems to be simple, made to satiate the desires of the audi- ence—primarily heterosexual males—however there are arguments to be made that Showgirls is so much more than that. This essay is in two sections: firstly, this part will contextualise the film, acknowledge some of the film’s criticisms, and will then go on to consider the film as a postmodern self-critique. The second instalment will go on to analyse Showgirls as an indictment of America in terms of its hegemonic structures, artificiality, its exploitative nature, and stardom. There is just so much interesting context to Showgirls, including the choices of direc- tor and writer, casting, budget, marketing, Hollywood studios, and the certification of the film. Showgirls is directed by Paul Verhoeven, whose reputation had grown with multiple successes in his native Netherlands before making the successful Hollywood films Robocop (1987) and Total Recall (1990). It was with his 1992 erotic thriller, Basic Instinct, that Verhoeven really became a household name director. -

Telling Lies in America Joe Eszterhas Is a Big-Bucks Screenwriter Who

Telling Lies in America Joe Eszterhas is a big-bucks screenwriter who earned millions for slick trash (like Flashdance and Basic Instinct) and total trash (Jade, Showgirls) but who now has returned to his roots with his latest script. Very different from his previous efforts is Telling Lies to America , a coming of age story about a Hungarian immigrant kid growing up poor and ambitious in Cleveland (Eszterhas’ hometown), in the early 1960’s era of burgeoning rock n’ roll. The kid is teenager Karchy Jonas (Brad Renfro), an outsider at his high school who still has trouble pronouncing that tough “th” of English and who has to work nights at an egg plant to help support his factory worker father (Maximilian Schell). Karchy has an inchoate desire for a better life and grabs his chance when a local celebrity, slick disc jockey Billy Magic (Kevin Bacon) takes him on as a go-fer. Billy, willing to plug teenybopper tunes for dough, really loves rhythm and blues (what he calls “sweaty collars and dirty fingernails music”), and he humors Karchy because he recognizes his own deceitful youth in the lad. In a new cool jacket, Karchy dreams of being a dj himself, complete with the girls, the hot car, and the flash he sees Billy possesses. His newfound hustle, however, loses him the respect of his old-country father and his co-worker and girlfriend Diney (Calista Flockhart), and, when he gets mired in Billy’s payola schemes as a material witness for government investigators, he learns the price of prevaricating to get ahead. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation.