Child Support Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TENTH REPORT Independent Monitor for the Maricopa County Sheriff's Office Reporting Period

Case 2:07-cv-02513-GMS Document 1943 Filed 02/10/17 Page 1 of 237 TENTH REPORT Independent Monitor for the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office Reporting Period – Third Quarter 2016 Robert S. Warshaw Independent Monitor February 10, 2017 Case 2:07-cv-02513-GMS Document 1943 Filed 02/10/17 Page 2 of 237 Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction…………………………………………………...……..3 Section 2: Methodology and Compliance Summary…………………………...5 Section 3: Implementation Unit Creation and Documentation Request………..8 Section 4: Policies and Procedures……………………..………………….….12 Section 5: Pre-Planned Operations………………………………..…….……..41 Section 6: Training………………………………………………………….....46 Section 7: Traffic Stop Documentation and Data Collection……………..…...58 Section 8: Early Identification System (EIS)………….………………..…......95 Section 9: Supervision and Evaluation of Officer Performance…….…….....123 Section 10: Misconduct and Complaints…………………………………......143 Section 11: Community Engagement………………………………………...148 Section 12: Misconduct Investigations, Discipline, and Grievances………...155 Section 13: Community Outreach and Community Advisory Board………..214 Section 14: Supervision and Staffing………………………………………...215 Section 15: Document Preservation and Production…………………………218 Section 16: Additional Training……………………………………………...220 Section 17: Complaints and Misconduct Investigations Relating to Members of the Plaintiff Class………………………………....221 Section 18: Concluding Remarks………………………………………….....235 Appendix: Acronyms………………………………………………………...237 Page 2 of 237 Case 2:07-cv-02513-GMS -

Copyrighted Material

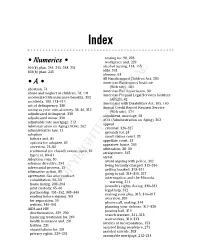

30_558307 bindex.qxd 1/24/05 6:52 PM Page 351 Index testing for, 90, 223 • Numerics • workplace and, 229 401(k) plan, 244, 245, 248, 251 alcohol testing, 114, 115 403(b) plan, 245 alibi, 318 alimony, 63 All Handicapped Children Act, 230 • A • American Bankruptcy Institute (Web site), 184 abortion, 74 American Bar Association, 30 abuse and neglect of children, 78, 141 American Prepaid Legal Services Institute accelerated life insurance benefits, 302 (APLSI), 42 accidents, 103, 113–114 Americans with Disabilities Act, 105, 160 act of delinquency, 330 Annual Credit Report Request Service acting as your own attorney, 34, 46, 312 (Web site), 174 adjudicated delinquent, 330 annulment, marriage, 58 adjudicated minor, 330 AOA (Administration on Aging), 262 adjustable rate mortgage, 212 appeal Administration on Aging (AOA), 262 criminal, 326–327 administrative law, 11 grounds for, 24 adoption small claims court, 33 fathers and, 81 appellate court, 13 options for adoptee, 82 appraiser, home, 205 overview, 79–80 arbitration, 28, 30 traditional (or closed) versus open, 82 arraignment, 315 types of, 80–81 arrest Adoption.com, 80 avoid arguing with police, 342 advance directive, 294 being formally charged, 315–316 adversarial process, 15 getting booked, 313–314 affirmative action, 89 going to jail, 314–315, 327 agreement. See also contract interrogation and the Miranda cohabitation, 50–53 warning, 311 home listing, 203–204 juvenile’s rights during, 330–331 joint custody, 65–66COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL legal help, 312 partnership, 151–152, 343–344 making -

Interstate Child Support Enforcement After United States V. Lopez

COMMENTS MAKING PARENTS PAY: INTERSTATE CHILD SUPPORT ENFORCEMENT AFTER UNITED STATES V. LOPEZ KATHLEEN A. BURDETTEt INTRODUCTION When Jeffrey Nichols, a wealthy consultant, decided to divorce his wife of sixteen years in order to marry a younger woman, he was ordered to pay $9000 a month in support for his three children.' Believing that the children's grandfather would support them, Nichols ignored his child support obligations and, instead, lived in luxury with his second wife for over five years.2 After cleaning out his accounts in New York, where the children and his ex-wife still reside, he moved to Toronto.3 In an attempt to evade law enforce- ment officials who make it their business to search for "deadbeat dads," Nichols then moved to Boca Raton, Florida and later to Vermont.4 He also attempted to conceal some of his assets by placing them in his second wife's name and in offshore accounts that could not be traced.5 The law finally caught up with Nichols when his second wife, in the process of filing for divorce, signed an affidavit stating that Nichols had been avoiding child support payments for five years.' Nichols, who spent four months in a New York jail,7 owes more t" B.A. 1994, Cornell University;J.D. Candidate 1997, University of Pennsylvania. I would like to thank Professor Seth Kreimer for listening to my ideas at various stages of their development. I am also grateful to my Law Review editors, Pamela Reichlin, Karin Guiduli, and Laura Boschken, for their suggestions. Special thanks to David Shields, who has encouraged me throughout my time at the Law School. -

2016 Showdown? Evan the Hesitant Needs More Time to De- Former Governor Cide Whether He’Ll Try to Still Undecided on Recapture His Old Job

V19, N41 Tuesday, July 8, 2014 2016 Showdown? Evan the hesitant needs more time to de- Former governor cide whether he’ll try to still undecided on recapture his old job. “I think it’s less likely a challenge to than more likely,” he said. “I haven’t ruled it Gov. Pence out.” Bayh cited family By MAUREEN HAYDEN as the reason for delay, CNHI Statehouse Bureau during a recent interview WASHINGTON – Evan in the Washington D.C. Bayh is keeping Indiana Demo- offices of McGuireWoods, crats on hold. a law and lobbying firm Party loyalists longing he joined when he left for a political savior to retake the Senate. He’s been the governor’s office have been busy advising the firm’s waiting on Bayh ever since he banking and energy abruptly decided to leave the clients, in addition to U.S. Senate and political life his work with a New three years ago. York private equity firm, For now, it appears, Apollo Global Manage- they’ll just have to keep waiting, ment, and with stint as a perhaps well into this fall. Fox News contributor. Despite a hefty cam- Former two-term Gov. Evan Bayh attended Gov. Mike Pence’s 2013 His twin sons, paign war chest and deep nos- inaugural. He is now weighing a challenge to the Republican, who talgia for his days as a popular may opt out for a presidential bid. Continued on page 4 centrist Democrat, Bayh says he ‘Deadbeat parent’ state By BRIAN A. HOWEY FREMONT, Ind. – In his State of the State address last January, Gov. -

Supreme Court of the United States

Nos. 14-556, 14-562, 14-571 and 14-574 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States JAMES OBERGEFELL, ET AL., AND BRITTANI HENRY, ET AL., PETITIONERS, v. RICHARD HODGES, DIRECTOR, OHIO DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, ET AL., RESPONDENTS. VALERIA TANCO, ET AL., PETITIONERS, v. WILLIAM EDWARD “BILL” HASLAM, GOVERNOR OF TENNESSEE, ET AL., RESPONDENTS. APRIL DEBOER, ET AL., PETITIONERS, v. RICK SNYDER, GOVERNOR OF MICHIGAN, ET AL., RESPONDENTS. GREGORY BOURKE, ET AL., AND TIMOTHY LOVE, ET AL., PETITIONERS, v. STEVE BESHEAR, GOVERNOR OF KENTUCKY, ET AL., RESPONDENT On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit _____________ AMICUS BRIEF OF THE CLEVELAND CHORAL ARTS ASSOCIATION INC A/K/A THE NORTH COAST MEN’S CHORUS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS Harlan D. Karp Tina R. Haddad Counsel of Record 3155 W.33rd St. 850 Euclid Ave. #1330 Cleveland, OH 44109 Cleveland, OH 44114 (216) 281-5210 (216) 685-1360 [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Amicus Curiae i Questions Presented 1) Does the Fourteenth Amendment require a state to license a marriage between two people of the same sex? 2) Does the Fourteenth Amendment require a state to recognize a marriage between two people of the same sex when their marriage was lawfully licensed and performed out-of-state? ii Table of Contents Page Questions Presented. i Table of Contents. ii Table of Authorities. iv Interest of Amicus Curiae. 1 Introduction and Statement. 2 Summary of Argument.. 7 Argument. 8 I. Where The Record Contains Explicit Statements Of Private Bias Against The Targeted Group, This Court Has Found The Presence Of Unconstitutional Animus. -

DSS 2013 Annual Report

Nassau County Department of Social Services Edward P. Mangano, County Executive John E. Imhof Ph.D., Commissioner Annual Report 2013 Artistic rendition of the Nassau County DSS customer service lobby at 60 Charles Lindbergh Blvd. in Uniondale, NY I. Message from the County Executive Nassau County Legislature 1550 Franklin Ave. Mineola, NY 11501 516-571-6200 Norma L. Gonsalves, Presiding Officer, LD 13 Kevan Abrahams, LD 1 Siela Bynoe, LD 2 Carrié Solages, LD 3 Denise Ford, LD 4 A Message from County Executive Ed Mangano: Laura Curran, LD 5 I am pleased to present the 2013 Annual Report of the Nassau County Department of Social Services (DSS). As a longtime public servant, I Francis X. Becker Jr., LD 6 understand the many challenges facing government, especially during times of economic stress and crises. As the safety net for our residents who Howard J. Kopel, LD 7 are facing economic distress, DSS and all of its dedicated staff perform an extraordinary job addressing the needs of individuals and families throughout our County. Vincent T. Muscarella, LD 8 Nassau County DSS has proven to be one of the most innovative and Richard J. Nicolello, LD 9 forward-thinking human services agencies in the nation, consistently enhancing its services and programs through on-going quality management Ellen Birnbaum, LD 10 initiatives that advocate innovation and efficiency in these days of limited financial resources. Of special note is the extensive efforts I have supported Delia DeRiggi-Whitton, LD 11 to root out Medicaid waste, fraud and abuse. In 2013, DSS fraud investigators uncovered $18 million in recipient and provider fraud, waste Michael Venditto, LD 12 and abuse across all program areas. -

The Paternity Test and the Cultural Logic of Paternity

WHO'S YOUR DADDY? THE PATERNITY TEST AND THE CULTURAL LOGIC OF PATERNITY by Kathalene A. Razzano A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cultural Studies Director Program Director Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: );! Spring Semester 2012 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Who’s Your Daddy?: The Paternity Test and the Cultural Logic of Paternity A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Kathalene A. Razzano Master of Arts The Pennsylvania State University, 1997 Bachelor of Arts University of Maryland, College Park, 1995 Director: Timothy Gibson, Professor Department of Communication Spring Semester 2012 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to those I’ve lost along the way; my teachers, mentors and friends Joe L. Kincheloe, Peter Brunette, and Jeanne Hall; my step-mother Linda Razzano; and my Pop, Gabriel Razzano. I miss each of you but carry you on with me. I also dedicate this dissertation to my Grammies, Audrey Razzano. She’s been waiting for me to (finally) finish so that she can call me “Doctor.” iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the many friends, relatives, and supporters who have made this happen. Since I’ve been doing this a while, I have a number of people to thank. First, I must thank my dissertation chair Tim Gibson who has been unbelievably supportive, helpful and productively critical. -

Phoenix Law Review

PHOENIX LAW REVIEW VOLUME 7FALL 2013 NUMBER 1 Published by Phoenix School of Law Phoenix, Arizona 85004 Published by Phoenix Law Review, Phoenix School of Law, One North Central Avenue,14th Floor, Phoenix, Arizona 85004. Phoenix Law Review welcomes the submission of manuscripts on any legal topic and from all members of the legal community. Submissions can be made via ExpressO at http://law.bepress.com/expresso, via e-mail to [email protected], or via postal service to: Submissions Editor Phoenix Law Review Phoenix School of Law 1 North Central Avenue 14th Floor Phoenix, Arizona 85004 We regret that manuscripts cannot be returned. All submissions should conform to the rules of citation contained in the most recent edition of The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citations, published by the Harvard Law Review Association. Phoenix Law Review is published twice each year or more by the Phoenix School of Law. Subscription rates are $50.00 per year for United States addresses and $64.00 per year for addresses in other countries. Subscriptions are renewed automatically unless notice to cancel is received. Subscriptions may be discontinued only at the expiration of the current volume. Direct all communications to the Administrative Editor at the address given above. Copyright © 2013 by Phoenix Law Review on all articles, comments, and notes, unless otherwise expressly indicated. Phoenix Law Review grants per- mission for copies of articles, comments, and notes on which it holds a copy- right to be made and used by nonprofit educational institutions, provided that the author and Phoenix Law Review are identified and proper notice is affixed to each copy. -

Hitting Deadbeat Parents Where It Hurts: Punitive Mechanisms in Child Support Enforcement

NOTES Hitting Deadbeat Parents Where it Hurts: "Punitive" Mechanisms in Child Support Enforcement This Note discusses the crisis created by "problem parents" who fail to meet their child support obligations. Alaska has not es- caped this crisis. This Note traces the efforts in Alaska to exact payment from child support obligors through both civil and criminal provisions. In particular,it discusses the recent expan- sion of criminalprovisions, including the criminalizationof aiding and abetting nonpayment of child support obligations and the suspension, revocation or denial of driver's and occupational li- censes. The Note suggests several ways in which Alaska can strengthen its criminalprovisions to improve enforcement, and it analyzes the constitutionality of Alaska's license revoca- tion/suspension provisions. Finally, the Note suggests another method by which to increase the rate of child support payment, namely the use of "most wanted" lists. I. INTRODUCTION The crisis in child support in the United States, and in Alaska, is one of immense proportions. This crisis can be traced directly to the failure of numerous noncustodial parents to make their child support payments. In 1992, only 54% of single-parent families with children had an established child support order.' Of those families, only about one-half received the full amount due.2 Stud- ies indicate that two-fifths of divorced fathers in the United States Copyright © 1997 by Alaska Law Review 1. See H.R. CONF. REP. No. 104-430, § 101(4) (1995), available in 1995 WL 767839, at *21. This statistic does not indicate that the remaining 46% of single- parent families have no method of child support. -

Prenatal Abandonment: 'Horton Hatches the Egg' in the Supreme Court and Thirty-Four States Mary M

University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications 2017 Prenatal Abandonment: 'Horton Hatches the Egg' in the Supreme Court and Thirty-Four States Mary M. Beck University of Missouri School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/facpubs Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation 24 Mich. J. Gender & L. 53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. PRENATAL ABANDONMENT: 'HORTON HATCHES THE EGG' IN THE SUPREME COURT AND THIRTY-FOUR STATES (Jvfary (,W 'Beck* This article addresses an issue critical to forty-one percent of fathers in the United States: prenatalabandonment. Under prenatal abandonment theory, fathers can lose their parental rights to non- marital children if they do not provide prenatal support to the mothers of their children. This is true even if the mothers have not notified the fathers of the pregnancy and if the mothers or fathers are unsure of the fathers'paternity. While this result may seem counter- intuitive, it is necessitated by demographic trends. Prenatalaban- donment theory has been structured to protect mothers, fathers, and fetuses in response to a number of socialfactors: the link between pregnancy and increased rates of sexual assault, domestic violence, and domestic homicide; the high non-marital birth rate; the com- monality of casualsexual relationships;the likelihood that non-mar- ital children will live in poverty; and poverty s deleterious effects upon children. -

Reforming Child Support to Improve Outcomes for Children and Families by Vicki Turetsky

The Abell Report Published by the Abell Foundation June 2019 | Volume 32 | Number 5 Reforming Child Support to Improve Outcomes for Children and Families by Vicki Turetsky TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 What is the child support program? .................................................................................................................. 4 Who does the child support program serve? ................................................................................................... 5 Why can child support collection be a problem for low-income families? .................................................... 7 II. CHILD SUPPORT GUIDELINES: SETTING ACCURATE ORDERS ........................................................................ 8 How well do orders reflect ability to pay? ......................................................................................................... 9 Do self-support reserves meet subsistence needs? ...................................................................................... 11 Do parents comply with support orders based on “potential” income? ..................................................... 12 What is “voluntary impoverishment”? .............................................................................................................. 14 What are “discretionary orders”? ..................................................................................................................... -

Center for Family Policy and Practice a Look at Arrests of Low-Income Fathers for Child Support Nonpayment

Center for Family Policy and Practice RACHEL DURFEE A Look at Arrests of Low-Income Fathers for Child Support Nonpayment Enforcement, Court and Program Practices JANUARY 2005 BY REBECCA MAY AND MARGUERITE ROULET A Look at Arrests of Low-Income Fathers for Child Support Nonpayment Enforcement, Court and Program Practices BY REBECCA MAY AND MARGUERITE ROULET TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 4 Introduction 5 ARRESTING FOR NONPAYMENT OF CHILD SUPPORT A Look at State and Local Practices Introduction 8 Documentation of Arrests for Nonpayment 10 State-by-State Findings 13 NOTES FROM CHILD SUPPORT COURTS Process and Issues Introduction 39 Process 41 Fees 44 Legal Representation 45 Conclusions 46 PROMISING PRACTICES FOR LOW-INCOME PARENTS Brief Program Descriptions 47 Project: PROTECT (PartnershipPartnership forfor RReintegrationeintegration ooff OfOffendersfenders Through Employment and Community Treatment) 49 Project I.M.P.A.C.T. and the Marin County Department of Child Support Services 50 Parents’ Fair Share and the Fathers Support Center 51 Critical Program Components 53 Project: PROTECT 54 Project I.M.P.A.C.T. and the Marin County Department of Child Support Services 55 Parents’ Fair Share and the Fathers Support Center 55 Additional Program Services 56 Program Contact Information 58 Footnotes 59 Center for Family Policy and Practice • 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This series of papers is part of a project made possible by funding from the Mott Founda- tion and the Public Welfare Foundation. We are extremely grateful for the opportunity to investigate and report on the material below as a result of their support. Many program staff and parents have helped to make this project pos- sible.