Ucin1250530675.Pdf (8.44

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Studies of Urban Freeways for the I-81 Challenge

Case Studies of Urban Freeways for The I-81 Challenge Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council February 2010 Case Studies for The I-81 Challenge Table of Contents OVERVIEW................................................................................................................... 2 Highway 99/Alaskan Way Viaduct ................................................................... 42 Lessons from the Case Studies........................................................................... 4 I-84/Hub of Hartford ........................................................................................ 45 Success Stories ................................................................................................... 6 I-10/Claiborne Expressway............................................................................... 47 Case Studies for The I-81 Challenge ................................................................... 6 Whitehurst Freeway......................................................................................... 49 Table 1: Urban Freeway Case Studies – Completed Projects............................. 7 I-83 Jones Falls Expressway.............................................................................. 51 Table 2: Urban Freeway Case Studies – Planning and Design Projects.............. 8 International Examples .................................................................................... 53 COMPLETED URBAN HIGHWAY PROJECTS.................................................................. 9 Conclusions -

CAREW TOWER-NETHERLAND PLAZA HOTEL Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CAREW TOWER-NETHERLAND PLAZA HOTEL Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: CAREW TOWER-NETHERLAND PLAZA HOTEL Other Name/Site Number: Starrett-Netherland Hotel 2. LOCATION Street & Number: TOWER: West Fifth Street and Fountain Square Not for publication:___ HOTEL: 35 West Fifth Street City/Town: Cincinnati Vicinity:___ State: Ohio County: Hamilton Code: 061 Zip Code: 45202 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-Local:___ District:___ Public-State:___ Site:___ Public-Federal:___ Structure:___ Object:___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 _____ buildings _____ _____ sites _____ _____ structures _____ _____ objects 1 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CAREW TOWER-NETHERLAND PLAZA HOTEL Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Conference Sponsorship

Useful Information Dear Conference Attendees: We are looking forward to welcoming you to the SQF International Conference at the Hilton Netherland Plaza in Cincinnati. Before you pack your bags and head off to Ohio, there are a few important things to note. We hope the following checklist will be helpful in preparing you for what promises to be a memorable conference experience! Email us if you have additional questions or concerns that are not addressed in this checklist. AGENDA Please familiarize yourself in advance with the agenda and the session descriptions, so that you can select the activities you want to attend prior to arriving. On Wednesday, there are 10 breakout sessions that will be repeated in the afternoon. You can therefore attend a maximum of 4 out of 10 breakout sessions on that day. On Thursday, we will offer 8 sessions and you will be able to select 2 out of 8. If you are bringing more than one person from your company, we suggest you divide and conquer and make copious notes, so that you can report back to your team. Remember, the majority of the presentations will be available online prior to and after the conference (see “Presentations”). Download the latest agenda and session descriptions Room names are printed underneath the session title. A map of the hotel is provided in the workbook (and in this document) and there will be signs directing you. ARRIVAL When you arrive for the conference, please proceed to the Registration Desk outside the Pavilion Ballroom on the 4th Floor (see “Room Locations”). -

S.E. Johnson Companies, Inc., Docket No. 01-0456

United States of America OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH REVIEW COMMISSION 1924 Building - Room 2R90, 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303-3104 Secretary of Labor, Complainant, v. OSHRC Docket No. 01-0456 S. E. Johnson Companies, Inc., Respondent. Appearances: Paul G. Spanos, Esq., Office of the Solicitor, U. S. Department of Labor, Cleveland, Ohio For Complainant Jack Zouhary, Esq., S. E. Johnson Companies, Maumee, Ohio For Respondent Before: Administrative Law Judge Nancy J. Spies DECISION AND ORDER S. E. Johnson Companies (S. E. Johnson) is a general contractor specializing in heavy construction, such as bridges and highways. On September 18, 2000, an employee of S. E. Johnson’s subcontractor fell 17 feet from an elevated work platform and was severely injured. On October 18, 2000, as part of its local fall emphasis program, Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) compliance officer Steven Medlock investigated the circumstances surrounding the accident (Tr. 21-22). As a result of the inspection, OSHA issued S. E. Johnson a serious citation on February 16, 2001. The Secretary alleges that S. E. Johnson insufficiently pre-planned for adequate fall protection in violation of § 1926.502(a)(2) (item 1). She further asserts that a section of guardrail had only one railing and that it was not anchored to withstand 200 pounds of force in violation of §§ 1926.502(b)(2) (item 2) and 1926.502(b)(3) (item 3). S. E. Johnson denies the allegations and asserts that if any violation occurred it was the result of the misconduct of the subcontractor’s employee. For the reasons that follow, the Secretary failed to prove a violation for oversight and fall protection planning (item 1). -

Revive Cincinnati: Lower Mill Creek Valley

revive cincinnati: neighborhoods of the lower mill creek valley Cincinnati, Ohio urban design associates february 2011 STEERING COMMITTEE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE Revive Cincinnati: Charles Graves, III Tim Jeckering Michael Moore Emi Randall Co-Chair, City Planning and Northside Community Council Chair, Transportation and OKI Neighborhoods of the Lower Buildings, Director Engineering Dave Kress Tim Reynolds Cassandra Hillary Camp Washington Business Don Eckstein SORTA Mill Creek Valley Co-Chair, Metropolitan Sewer Association Duke Energy Cameron Ross District of Greater Cincinnati Mary Beth McGrew Patrick Ewing City Planning and Buildings James Beauchamp Uptown Consortium Economic Development PREPARED FOR Christine Russell Spring Grove Village Community Weston Munzel Larry Falkin Cincinnati Port Authority City of Cincinnati Council Uptown Consortium Office of Environmental Quality urban design associates 2011 Department of City Planning David Russell Matt Bourgeois © and Buildings Rob Neel Mark Ginty Metropolitan Sewer District of CHCURC In cooperation with CUF Community Council Greater Cincinnati Waterworks Greater Cincinnati Metropolitan Sewer District of Robin Corathers Pat O’Callaghan Andrew Glenn Steve Schuckman Greater Cincinnati Mill Creek Restoration Project Queensgate Business Alliance Public Services Cincinnati Park Board Bruce Demske Roxanne Qualls Charles Graves Joe Schwind Northside Business Association CONSULTANT TEAM City Council, Vice Mayor City Planning and Buildings, Director Cincinnati Recreation Commission Urban Design Associates Barbara Druffel Walter Reinhaus LiAnne Howard Stefan Spinosa Design Workshop Clifton Business and Professional Over-the-Rhine Community Council Health ODOT Wallace Futures Association Elliot Ruther Lt. Robert Hungler Sam Stephens Robert Charles Lesser & Co. Jenny Edwards Cincinnati State Police Community Development RL Record West End Community Council DNK Architects Sandy Shipley Dr. -

Cincinnati: Many Rivers Run Through It

Cincinnati: Many Rivers Run Through It Susan Paddock Attendees at ICMA’s 86th Annual Conference 2000 in September, held in Cincinnati/ Hamilton County, will see that the Ohio River is a fascinating local asset. Downtown and riverfront development means that more attractions are yet to come. Cincinnati always has been defined by its relationship to the Ohio River. This enviable river location symbolizes the success Cincinnati enjoys as an ever- changing place to live, work, and play. Cincinnati’s early development was a direct result of its access to the river because commerce thrives in a location with a transportation advantage. Growth and development in the downtown and on the riverfront reflect the “rivers” that now flow through the city, as well as next to it. Cincinnati’s rivers of vitality, tradition, information, creativity, and opportunity demonstrate the city’s advantages not only in transportation but also in quality of life, historic preservation, technology, the arts, and development. River of Vitality Streams of people living, working, and playing in Cincinnati contribute to its urban environment. In particular, the city’s broad-ranging, well-planned housing options create a 24-hour city full of vitality. Eugenie Birch, professor and chair of the department of city and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania, has compared housing trends in 40 cities from 1990 to 1999. She found in her 1999 study “Downtown Living: A Deeper Look” that Cincinnati had one of the more robust markets in downtown housing in the United States. “Cincinnati is one of the brighter stories,” Ms. Birch says. -

Urban Design Master Plan

urban design associates Central Riverfront Urban Design Master Plan 33 Urban Design Master Plan urban design associates Central Riverfront Urban Design Master Plan i Urban Design the cincinnati central riverfront Urban Design Master 34 Plan is the result of a public participation planning process Master Plan begun in October 1996. Hamilton County and the City of Cincinnati engaged Urban Design Associates to prepare a plan to give direction in two public policy areas: • to site the two new stadiums for the Reds and the Bengals • to develop an overall urban design framework for the development of the central riverfront which would capitalize on the major public investment in the stadiums and parking A Riverfront Steering Committee made up of City and County elected officials and staff was formed as a joint policy board for the Central Riverfront Plan. Focus groups, inter- views, and public meetings were held throughout the planning process. A Concept Plan was published in April 1997 which identi- fied three possible scenarios for the siting of the stadiums and the development of the riverfront. The preparation of a final Master Plan was delayed due to a 1998 public referendum on the siting of the Reds Ballpark. Once the decision on the Reds Ballpark was made by the voters in favor of a riverfront site, Hamilton County and the City of Cincinnati in February 1999 appointed sixteen promi- nent citizens to the Riverfront Advisors Commission who were charged to “recommend mixed usage for the Riverfront that guarantees public investment will create sustainable develop- ment on the site most valued by our community.” The result of that effort was The Banks, a September 1999 report from the Advisors which contained recommendations on land use, park- ing, finance, phasing, and developer selection for the Central Riverfront. -

A Historical Bibliography of Commercial Architecture in the United States

A HISTORICAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE IN THE UNITED STATES Compiled by Richard Longstreth, 2002; last revised 7 May 2019 I have focused on historical accounts giving substantive coverage of the commercial building types that traditionally distinguish city and town centers, outlying business districts, and roadside development. These types include financial institutions, hotels and motels, office buildings, restaurants, retail and wholesale facilities, and theaters. Buildings devoted primarily to manufacturing and other forms of production, transportation, and storage are not included. Citations of writings devoted to the work of an architect or firm and to the buildings of a community are limited to a few of the most important relative to this topic. For purposes of convenience, listings are divided into the following categories: Banks; Hotels-Motels; Office Buildings; Restaurants; Taverns, etc.; Retail and Wholesale Buildings; Roadside Buildings, Miscellaneous; Theaters; Architecture and Place; Urbanism; Architects; Materials-Technology; and Miscellaneous. Most accounts are scholarly in nature, but I have included some popular accounts that are particularly rich in the historical material presented. Any additions or corrections are welcome and will be included in updated editions of this bibliography. Please send them to me at [email protected]. B A N K S Andrew, Deborah, "Bank Buildings in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia," in William Cutler, III, and Howard Gillette, eds., The Divided Metropolis: Social and Spatial Dimensions -

Request for Proposals Entertainment Venue and Event Center at the Banks

REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS ENTERTAINMENT VENUE AND EVENT CENTER AT THE BANKS THE REDEVELOPMENT OF OHIO’S SOUTHERN GATEWAY CINCINNATI, OHIO ISSUANCE DATE: FEBRUARY 15, 2018 PROPOSALS DUE: MARCH 15, 2018 REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS ENTERTAINMENT VENUE AND EVENT CENTER AT THE BANKS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Overview ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Project Site Description ..................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Development Timeline ...................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4. Inclusion Policy; Small Business Enterprise ....................................................................................................... 4 1.5. Ownership ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.6. Project Goals ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.7. Selection Process ............................................................................................................................................. -

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings January 30, 2019

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings January 30, 2019 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1919-The Reds hire Pat Moran as manager, replacing Christy Mathewson, when no word is received from him while his is in France with the U.S. Army. Moran would manage the Reds until 1923, collecting a 425-329 record 1978-Former Reds executive, Larry MacPhail, is elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 1997-The Reds sign Deion Sanders to a free agent contract, for the second time ESPN.COM Busy Reds in on Realmuto, but would he make them a contender? Jan. 29, 2019 Buster Olney ESPN Senior Writer The last time the Cincinnati Reds won a postseason series, Joey Votto was 12 years old, Bret Boone was the team's second baseman and the organization had only recently drafted his kid brother, a third baseman out of the University of Southern California named Aaron Boone. Since the Reds swept the Dodgers in a Division Series in 1995, they have built more statues than they have playoff wins. In recent years, a Dodger said he was sick of Kirk Gibson -- not because of anything Gibson had done, but because the team had felt the need to roll out the highlight of Gibson's epic '88 World Series home run, in lieu of subsequent championship success. Similarly, most of the biggest stars in the Reds organization continue to be Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, Pete Rose and Tony Perez, as well as announcer Marty Brennaman, who recently announced he will retire after the upcoming season. -

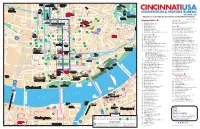

Map of Cincinnati Downtown

|1|2|3|4|5|6|7|8|9|10 | 11 | _ _ 20 73 57 85 79 71 25 18 39 A A 16 35 4 60 41 32 CincyUSA.com _ 34 _ 42 What to do in Downtown Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky 55 Locations on grid listed in ( ) 2 Entertainment Districts Shopping 101 B 49 B 1. The Banks (F-6) 12. Carew Tower Complex/Mabley Place (E-5) 24 8 31 23 81 2. Broadway Commons (B-7) 61. Saks Fifth Avenue (E-4) 3. Fountain Square (D & E-5) (A & B-6) 98 Jack 4. Main Street Hotels 30 _ 96 Casino _ 5. Mount Adams (B & C-10) 62. AC Hotel Cincinnati at the Banks (F-6) 5 6. Mainstrasse Village (J-2) 63. Aloft Newport-Cincinnati (H-10) (H-9 & 10) 17 7. Newport on the Levee 64. Best Western Plus Cincinnati Riverfront (I-1) 28 8. Over-The-Rhine Gateway Quarter (A & B-4 & 5 & 6) 65. Cincinnati Marriott at RiverCenter (I-4) C C 66. Cincinnatian Hotel (D-5) 27 Area Attractions 28 Public 67. Comfort Suites Newport (G-11) 91 Library 9. Aronoff Center for the Arts (D-6) 10. BB Riverboats Inc. (H-8) 68. Courtyard by Marriott Covington (I-2) 89 69. Embassy Suites at RiverCenter (I-5) _ 102 97 Belterra Park _ 11. Bicentennial Park (F-9) 75 Gaming 12. Carew Tower Complex 70. Extended Stay America – Covington (I-1) Observation Deck (E-5) 71. Farfield Inn & Suites Cincinnati/Uptown (See other side) (A-5) 88 13. -

Cincinnati in 1851

CINC INNATI ChristmasHISTORY • TRADITION • FOOD Jinny Powers Berten FORT WASHINGTON Fort Washington, drawn in 1790 by Captain Jonathan Heart, who was killed in the Battle of the Wabash the next year. Published in Charles Cist’s Sketches and Statistics of Cincinnati in 1851. 6 Cincinnati Christmas T he Early Years 1826–1850 Cincinnati 1800, from the program for the celebration of Nicholas and Susan Howell Longworth’s fiftieth wedding anniversary, 1857. From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County Hiatory 9 Christmas and the City Expand 1850–1860 Cincinnati 1857, from the program for the celebration of Nicholas and Susan Howell Longworth’s fiftieth wedding anniversary, 1857. From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County 18 Cincinnati Christmas Left: Program from Nicholas and Susan Howell Longworth’s fiftieth-anniversary celebration. From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County Below: Poem from Longworths’ anniversary celebration program. From the collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County History 21 Above: Shillito’s Christmas catalogue, 1878. Courtesy Cincinnati Museum Center/Cincinnati Historical Society Library Right: Cincinnati Orphan Asylum Christmas appeal, 1876. Courtesy Cincinnati Museum Center/Cincinnati Historical Society Library History 25 Fountain Square Pantomime was painted by Cincinnati artist Joseph Henry Sharp in 1892. Cincinnati Art Museum. Gift of the CAM Docent Organization in celebration of its fortieth anniversary and The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial. 2000 68. 26 Cincinnati Christmas Fountain Square stores put on small holiday plays. Mabley & Carew pre- sented pantomimes on a large glass-covered balcony facing Fountain Square.