Redalyc.HUGO CHAVEZ's POLARIZING LEGACY: CHAVISMO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explaining Chavismo

Explaining Chavismo: The Unexpected Alliance of Radical Leftists and the Military in Venezuela under Hugo Chávez by Javier Corrales Associate Professor of Political Science Amherst College Amherst, MA 01002 [email protected] March 2010 1 Knowing that Venezuela experienced a profound case of growth collapse in the 1980s and 1990s is perhaps enough to understand why Venezuela experienced regime change late in the 1990s. Most political scientists agree with Przeworski et al. (2000) that severe economic crises jeopardize not just the incumbents, but often the very continuity of democratic politics in non-rich countries. However, knowledge of Venezuela’s growth collapse is not sufficient to understand why political change went in the direction of chavismo. By chavismo I mean the political regime established by Hugo Chávez Frías after 1999. Scholars who study Venezuelan politics disagree about the best label to describe the Hugo Chávez administration (1999-present): personalistic, popular, populist, pro-poor, revolutionary, participatory, socialist, Castroite, fascist, competitive authoritarian, soft- authoritarian, third-world oriented, hybrid, statist, polarizing, oil-addicted, ceasaristic, counter-hegemonic, a sort of Latin American Milošević, even political ―carnivour.‖ But there is nonetheless agreement that, at the very least, chavismo consists of a political alliance of radical-leftist civilians and the military (Ellner 2001:9). Chávez has received most political advice from, and staffed his government with, individuals who have an extreme-leftist past, a military background, or both. The Chávez movement is, if nothing else, a marriage of radicals and officers. And while there is no agreement on how undemocratic the regime has become, there is virtual agreement that chavismo is far from liberal democracy. -

Alba and Free Trade in the Americas

CUBA AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF ALTERNATIVE GLOBAL TRADE SYSTEMS: ALBA AND FREE TRADE IN THE AMERICAS LARRY CATÁ BACKER* & AUGUSTO MOLINA** ABSTRACT The ALBA (Alternativa Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América) (Bolivarian Alternative for The People of Our America), the command economy alternative to the free trade model of globalization, is one of the greatest and least understood contributions of Cuba to the current conversation about globalization and economic harmonization. Originally conceived as a means for forging a unified front against the United States by Cuba and Venezuela, the organization now includes Nicaragua, Honduras, Dominica, and Bolivia. ALBA is grounded in the notion that globalization cannot be left to the private sector but must be overseen by the state in order to maximize the welfare of its citizens. The purpose of this Article is to carefully examine ALBA as both a system of free trade and as a nexus point for legal and political resistance to economic globalization and legal internationalism sponsored by developed states. The Article starts with an examination of ALBA’s ideology and institutionalization. It then examines ALBA as both a trade organization and as a political vehicle for confronting the power of developed states in the trade context within which it operates. ALBA remains * W. Richard and Mary Eshelman Faculty Scholar and Professor of Law, Dickinson Law School; Affiliate Professor, School of International Affairs, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania; and Director, Coalition for Peace & Ethics, Washington, D.C. The author may be contacted at [email protected]. An earlier version of this article was presented at the Conference, The Measure of a Revolution: Cuba 1959-2009, held May 7–9, 2009 at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. -

Redalyc.Venezuela in the Gray Zone: from Feckless Pluralism to Dominant

Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Sistema de Información Científica Myers, David J.; McCoy, Jennifer L. Venezuela in the gray zone: From feckless pluralism to dominant power system Politeia, núm. 30, enero-junio, 2003, pp. 41-74 Universidad Central de Venezuela Caracas, Venezuela Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=170033588002 Politeia, ISSN (Printed Version): 0303-9757 [email protected] Universidad Central de Venezuela Venezuela How to cite Complete issue More information about this article Journal's homepage www.redalyc.org Non-Profit Academic Project, developed under the Open Acces Initiative 41 REVISTA POLITEIAVENEZUELA, N° 30. INSTITUTO IN THE DE GRAY ESTUDIOS ZONE: POLÍTICOS FROM, FECKLESSUNIVERSIDAD PLURALISM CENTRAL DE TO VENEZUELA DOMINANT, 2003:41-74 POWER SYSTEM 30 Politeia Venezuela in the gray zone: From feckless pluralism to dominant power system Venezuela en la zona gris: desde el pluralismo ineficaz hacia el sistema de poder dominante David J. Myers / Jennifer L. McCoy Abstract Resumen This paper emphasizes the need to measure the El presente texto resalta la necesidad de medir las varying qualities of democracy. It delineates subtypes diversas cualidades de la democracia. En este senti- of political regimes that occupy a “gray zone” between do, delinea los diferentes tipos de regímenes políti- dictatorship and democracy, and examines the cos que se encuentran en la denominada “zona gris” possibilities for political change in the “gray zone”. entre la dictadura y la democracia. Asimismo exami- The authors address two sets of questions about na las posibilidades de cambio dentro de dicha zona political change: a) What causes a limitedly pluralist gris. -

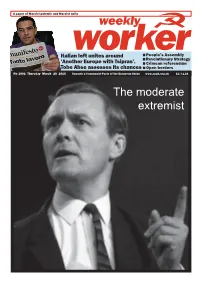

Weekly Worker March 13), Which of How I Understand the “From of Polemic

A paper of Marxist polemic and Marxist unity weekly Italian left unites around n People’s Assembly workern Revolutionary Strategy ‘Another Europe with Tsipras’. n Crimean referendum Tobe Abse assesses its chances n Open borders No 1002 Thursday March 20 2014 Towards a Communist Party of the European Union www.cpgb.org.uk £1/€1.10 The moderate extremist 2 weekly March 20 2014 1002 worker LETTERS Letters may have been in the elemental fight over wages definitively assert what he would What nonsense. Let us leave such shortened because of and conditions that would occur in Xenophobic have said then!” True enough (and window dressing to the Trots! space. Some names class society even if there was no I cannot escape the conclusion that fortunately for him nor was there Those on the left should ensure may have been changed such thing as Marxism. The fact that there exists a nasty xenophobic any asylum-seekers legislation for that those they employ are paid today “the works of Marx, Lenin undertone to Dave Vincent’s reply political refugees), but Eleanor, his transparently, in line with the Not astounding and others [are] freely available (Letters, March 13). daughter, was particularly active in market rate, and ensure best value In spite of all the evidence that I have on the internet” changes nothing in First, has Dave never heard of the distributing the statement, “The voice for money for their members. Crow put forward from Lars T Lih’s study, this regard, except for the fact that Irish immigration to Scotland and of the aliens’, which I recommended fulfilled all those requirements, Lenin rediscovered, in particular, uploading material onto a website in particular to the Lanarkshire coal as a read. -

The Radical Potential of Chavismo in Venezuela the First Year and a Half in Power by Steve Ellner

LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES Ellner / RADICAL POTENTIAL OF CHAVISMO The Radical Potential of Chavismo in Venezuela The First Year and a Half in Power by Steve Ellner The circumstances surrounding Hugo Chávez’s pursuit of power and the strategy he has adopted for achieving far-reaching change in Venezuelaare in many ways without parallel in Latin American politics. While many generals have been elected president, Chávez’s electoral triumph was unique in that he was a middle-level officer with radical ideas who had previously led a coup attempt. Furthermore, few Latin American presidents have attacked existing democratic institutions with such fervor while swearing allegiance to the democratic system (Myers and O’Connor, 1998: 193). From the beginning of his political career, Chávez embraced an aggres- sively antiparty discourse. He denounced the hegemony of vertically based political parties, specifically their domination of Congress, the judicial sys- tem, the labor and peasant movements, and civil society in general. Upon his election in December 1998, he followed through on his campaign promise to use a constituent assembly as a vehicle for overhauling the nation’s neo- corporatist political system. He proposed to replace this model with one of direct popular participation in decision making at the local level. His actions and rhetoric, however, also pointed in the direction of a powerful executive whose authority would be largely unchecked by other state institutions. Indeed, the vacuum left by the weakening of the legislative and judicial branches and of government at the state level and the loss of autonomy of such public entities as the Central Bank and the state oil company could well be filled by executive-based authoritarianism. -

Anti-Politics and Social Polarisation in Venezuela 1998-2004

1 Working Paper no.76 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ANTI- POLITICS AND SOCIAL POLARISATION IN VENEZUELA, 1998-2004 Jonathan DiJohn Crisis States Research Centre December 2005 Copyright © Jonathan DiJohn, 2005 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Research Centre The Political Economy of Anti-Politics and Social Polarisation in Venezuela 1998-2004 Jonathan DiJohn Crisis States Research Centre In the past twenty years, there has been a sharp decline in party politics and the rise of what can best be described as a new form of populist politics. Nowhere has this trend been more evident than in Latin America in the 1990s, particularly in the Andean region.1 One common theme in this trend is the rise of leaders who denounce politics by attacking political parties as the source of corruption, social exclusion and poor economic management of the -

Cuba and Alba's Grannacional Projects at the Intersection of Business

GLOBALIZATION AND THE SOCIALIST MULTINATIONAL: CUBA AND ALBA’S GRANNACIONAL PROJECTS AT THE INTERSECTION OF BUSINESS AND HUMAN RIGHTS Larry Catá Backer The Cuban Embargo has had a tremendous effect on forts. Most of these have used the United States, and the way in which Cuba is understood in the global le- its socio-political, economic, cultural and ideological gal order. The understanding has vitally affected the values as the great foil against which to battle. Over way in which Cuba is situated for study both within the course of the last half century, these efforts have and outside the Island. This “Embargo mentality” had mixed results. But they have had one singular has spawned an ideology of presumptive separation success—they have propelled Cuba to a level of in- that, colored either from the political “left” or fluence on the world stage far beyond what its size, “right,” presumes isolation as the equilibrium point military and economic power might have suggested. for any sort of Cuban engagement. Indeed, this “Em- Like the United States, Cuba has managed to use in- bargo mentality” has suggested that isolation and ternationalism, and especially strategically deployed lack of sustained engagement is the starting point for engagements in inter-governmental ventures, to le- any study of Cuba. Yet it is important to remember verage its influence and the strength of its attempted that the Embargo has affected only the character of interventions in each of these fields. (e.g., Huish & Cuba’s engagement rather than the possibility of that Kirk 2007). For this reason, if for no other, any great engagement as a sustained matter of policy and ac- effort by Cuba to influence behavior is worth careful tion. -

Participatory Democracy in Chávez's Bolivarian Revolution

Who Mobilizes? Participatory Democracy in Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution Kirk A. Hawkins ABSTRACT This article assesses popular mobilization under the Chávez gov- ernment’s participatory initiatives in Venezuela using data from the AmericasBarometer survey of 2007. This is the first study of the so- called Bolivarian initiatives using nationally representative, individ- ual-level data. The results provide a mixed assessment. Most of the government’s programs invite participation from less active seg- ments of society, such as women, the poor, and the less educated, and participation in some programs is quite high. However, much of this participation clusters within a narrow group of activists, and a disproportionate number of participants are Chávez supporters. This partisan bias probably reflects self-screening by Venezuelans who accept Chávez’s radical populist discourse and leftist ideology, rather than vote buying or other forms of open conditionality. Thus, the Venezuelan case suggests some optimism for proponents of par- ticipatory democracy, but also the need to be more attuned to its practical political limits. uring the past decade, leftist governments with participatory dem- Docratic agendas have come to power in many Latin American coun- tries, implementing institutional reforms at the local and, increasingly, the national level. This trend has generated a scholarly literature assess- ing the nature of participation in these initiatives; that is, whether they embody effective attempts at participatory forms of democracy that mobilize and empower inactive segments of society (Goldfrank 2007; Wampler 2007a). This article advances this discussion by studying popular mobiliza- tion under the government of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, referred to here as the Bolivarian Revolution or Chavismo. -

Partisanship During the Collapse Venezuela's Party System

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Political Science Publications and Other Works Political Science February 2007 Partisanship During the Collapse Venezuela's Party System Jana Morgan University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_polipubs Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Morgan, Jana, "Partisanship During the Collapse Venezuela's Party System" (2007). Political Science Publications and Other Works. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_polipubs/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Partisanship during the C ollapse of V enezuela’ S Part y S y stem * Jana Morgan University of Tennessee Received: 9-29-2004; Revise and Resubmit 12-20-2004; Revised Received 12-20-2005; Final Acceptance 4-03-2006 Abstract: Political parties are crucial for democratic politics; thus, the growing incidence of party and party system failure raises questions about the health of representative democracy the world over. This article examines the collapse of the Venezuelan party system, arguably one of the most institutionalized party systems in Latin America, by examining the individual-level basis behind the exodus of partisans from the traditional parties. Multinomial logit analysis of partisan identification in 1998, the pivotal moment of the system’s complete col- lapse, indicates that people left the old system and began to support new parties because the traditional parties failed to incorporate and give voice to important ideas and interests in society while viable alternatives emerged to fill this void in representation. -

The Bolivarian Dream: ALBA and the Cuba-Venezuela Alliance

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-5-2020 The Bolivarian Dream: ALBA and the Cuba-Venezuela Alliance Victor Lopez Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lopez, Victor, "The Bolivarian Dream: ALBA and the Cuba-Venezuela Alliance" (2020). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 4573. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/4573 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERISTY Miami, Florida THE BOLIVARIAN DREAM: ALBA AND THE CUBA-VENEZUELA ALLIANCE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in INTERNATIONAL STUDIES by Victor Lopez 2020 To: Dean John Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Victor Lopez, and entitled The Bolivarian Dream: ALBA and the Cuba- Venezuela Alliance, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Jorge Duany Eduardo Gamarra Astrid Arrarás, Major Professor Date of defense: November 5, 2020 The thesis -

The Reproduction and Crisis of Capitalism in Venezuela Under Chavismo by Fernando Dachevsky and Juan Kornblihtt Translated by Victoria J

LAPXXX10.1177/0094582X16673633LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVESDachevsky and Kornblihtt 673633research-article2016 The Reproduction and Crisis of Capitalism in Venezuela under Chavismo by Fernando Dachevsky and Juan Kornblihtt Translated by Victoria J. Furio The current crisis in Venezuela is sometimes said to have been provoked by the response of imperialism and the local oligarchy to the fundamental changes in economic and political relations fostered during the administrations of Hugo Chávez. A quantitative study using various statistical sources shows that the significant increase in oil rent during the Chávez presidency did not translate into a qualitative transformation in the form of state interven- tion and that, although social expenditures increased in that period, most of the income that allowed this was obtained through currency overvaluation by inefficient national and for- eign capital. The current crisis is, therefore, evidence of the limits of low-productivity state and private capital reproduction due to the decline in oil prices rather than of a conflict between overcoming and reproducing capitalism in an alleged “economic war.” A veces se dice que la crisis actual en Venezuela ha sido provocada por la respuesta del imperialismo y la oligarquía local a los cambios profundos en las relaciones económi- cas y políticas promovidos durante la administración de Hugo Chávez. Un estudio cuantitativo en el que se usaron diferentes fuentes estadísticas demuestra que el aumento significativo en la renta del petróleo durante la presidencia de Chávez no se tradujo en una transformación cualitativa de la intervención estatal y que, aunque los gastos soci- ales aumentaron en ese período, la mayor parte del ingreso que permitió ese aumento se obtuvo por medio de la sobrevaluación de la moneda por parte del ineficiente capital nacional y extranjero. -

Hugo Chávez's Death

Hugo Chávez’s Death: Implications for Venezuela and U.S. Relations Mark P. Sullivan Specialist in Latin American Affairs April 9, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42989 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Hugo Chávez’s Death: Implications for Venezuela and U.S. Relations he death of Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez on March 5, 2013, after 14 years of populist rule, has implications not only for Venezuela’s political future, but potentially for Tthe future of U.S.-Venezuelan relations. This report provides a brief discussion of those implications. For additional background on President Chávez’s rule and U.S. policy, see CRS Report R40938, Venezuela: Issues for Congress, by Mark P. Sullivan. Congress has had a strong interest in Venezuela and U.S. relations with Venezuela under the Chávez government. Among the concerns of U.S. policymakers has been the deterioration of human rights and democratic conditions, Venezuela’s significant military arms purchases, lack of cooperation on anti-terrorism efforts, limited bilateral anti-drug cooperation, and Venezuela’s relations with Cuba and Iran. The United States traditionally enjoyed close relations with Venezuela, but there has been considerable friction in relations under the Chávez government. U.S. policymakers have expressed hope for a new era in U.S.-Venezuelan relations in the post-Chávez era. While this might not be possible while Venezuela soon gears up for a presidential campaign, there may be an opportunity in the aftermath of the election. The Venezuelan Constitution calls for a new presidential election within 30 days; an election has now been scheduled for April 14, 2013.