The Rufford Foundation Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Checklist of Florida'a Birds

Artwork by Ann Marie Tavares 2016 Checklist of Florida’s Birds Prepared by Dr. Greg Schrott and Andy Wraithmell The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Florida’s wild places are home to an incredible diversity of birds. Over 500 native bird species or naturally occurring strays have been recorded in the state in historic times, and about 330 native species commonly occur here (four have gone extinct). A further 14 nonnative species are considered to have established large, stable populations in Florida. More than 70 natural community types support this diversity, from the pine flatwoods of Apalachicola National Forest, to the scrub communities of the Lake Wales Ridge, and the vast sawgrass marshes and mangrove swamps of Everglades National Park. Our natural areas harbor many bird species seen nowhere else in the United States such as the Florida Scrub-Jay, Mangrove Cuckoo, and Snail Kite. In addition, Florida’s birdlife changes with the cycle of the seasons. A constant turnover of breeding, wintering and migratory species provides new birding experiences throughout the year. To help you keep track of the spectacular range of birdlife the state has to offer, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) has published this checklist. The first edition of Checklist of Florida’s Birds was prepared by Dr. Henry M. Stevenson in 1986. During his lifetime, Dr. Stevenson made many contributions to the field of ornithology, culminating with his writing The Birdlife of Florida with Bruce H. Anderson (1994). This book offers the most comprehensive information published on the lives of Florida’s birds. -

The Evolution of Nest Construction in Swallows (Hirundinidae) Is Associated with the Decrease of Clutch Size

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 38/1 711-716 21.7.2006 The evolution of nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae) is associated with the decrease of clutch size P. HENEBERG A b s t r a c t : Variability of the nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae) is more diverse than in other families of oscine birds. I compared the nest-building behaviour with pooled data of clutch size and overall hatching success for 20 species of swallows. The clutch size was significantly higher in temperate cavity-adopting swallow species than in species using other nesting modes including species breeding in evolutionarily advanced mud nests (P<0.05) except of the burrow-excavating Bank Swallow. Decrease of the clutch size during the evolution of nest construction is not compensated by the increase of the overall hatching success. K e y w o r d s : Hirundinidae, nest construction, clutch size, evolution Birds use distinct methods to avoid nest-predation: active nest defence, nest camouflage and concealment or sheltered nesting. While large and powerful species prefer active nest-defence, swallows and martins usually prefer construction of sheltered nests (LLOYD 2004). The nests of swallows vary from natural cavities in trees and rocks, to self-exca- vated burrows to mud retorts and cups attached to vertical faces. Much attention has been devoted to the importance of controlling for phylogeny in com- parative tests (HARVEY & PAGEL 1991), including molecular phylogenetic studies of swallows (WINKLER & SHELDON 1993). Interactions between the nest-construction va- riability and the clutch size, however, had been ignored. -

Tree Swallow in Scilly: New to the Western Palearctic Jeremy Hickman

Tree Swallow in Scilly: new to the Western Palearctic Jeremy Hickman The Isles of Scilly is renowned as a haven for displaced migrant birds, and the autumn pilgrimage of observers in September and October is famous in ornithological circles. June is usually a quiet month for numbers of visiting birdwatchers, as are the other months outside the autumn, but June 1990 was the exception. In one five-day period, between 800 and 1,000 people came to see one bird: the first record for Britain & Ireland, Europe and the Western Palearctic of a North American species, Tree Swallow Tachycineta bicolor. On Wednesday 6th June 1990, having finished my shift behind the bar in the Mermaid Inn, I decided to go to Porth Hellick. I watched from the main hide for a while and could hardly believe how devoid of bird life it was. I could not even console myself by counting the Moorhens Gallinula chloropus. At about 19.00 BST, five hirundines approached low over the pool: one House Martin Delichon urbica, three Barn Swallows Hirundo rustica and another bird. This fifth bird gave the impression of a martin, but with no white rump and a glossy blue-green mantle and crown, and pure white underparts. My heart sank as the bird then flew to the back of the pool and began hawking around the pines and surrounding fields. I rushed to Sluice to obtain closer views and to note its plumage in detail. It appeared slightly bigger and bulkier in the body than a House Martin, with broader-based wings and more powerful flight. -

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 10.13

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 10.13 District of Columbia, Commonwealth sale, purchase, barter, exportation, and of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, U.S. importation of migratory birds. Virgin Islands, Guam, Commonwealth (c) What species are protected as migra- of the Northern Mariana Islands, Baker tory birds? Species protected as migra- Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, tory birds are listed in two formats to Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway suit the varying needs of the user: Al- Atoll, Navassa Island, Palmyra Atoll, phabetically in paragraph (c)(1) of this and Wake Atoll, and any other terri- section and taxonomically in para- tory or possession under the jurisdic- graph (c)(2) of this section. Taxonomy tion of the United States. and nomenclature generally follow the Whoever means the same as person. 7th edition of the American Ornitholo- Wildlife means the same as fish or gists’ Union’s Check-list of North Amer- wildlife. ican birds (1998, as amended through 2007). For species not treated by the [38 FR 22015, Aug. 15, 1973, as amended at 42 AOU Check-list, we generally follow FR 32377, June 24, 1977; 42 FR 59358, Nov. 16, Monroe and Sibley’s A World Checklist 1977; 45 FR 56673, Aug. 25, 1980; 50 FR 52889, Dec. 26, 1985; 72 FR 48445, Aug. 23, 2007] of Birds (1993). (1) Alphabetical listing. Species are § 10.13 List of Migratory Birds. listed alphabetically by common (English) group names, with the sci- (a) Legal authority for this list. The entific name of each species following Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) in the common name. -

Chapter 5: Maintaining Species in the South 113 Chapter 5

TERRE Chapter 5: Maintaining Species in the South 113 Chapter 5: S What conditions will be Maintaining Species TRIAL needed to maintain animal species associations in the South? in the South Margaret Katherine Trani (Griep) Southern Region, USDA Forest Service mammals of concern include the ■ Many reptiles and amphibians Key Findings Carolina and Virginia northern are long-lived and late maturing, flying squirrels, the river otter, and have restricted geographic ■ Geographic patterns of diversity and several rodents. ranges. Managing for these species in the South indicate that species ■ Twenty species of bats inhabit will require different strategies than richness is highest in Texas, Florida, the South. Four are listed as those in place for birds and mammals. North Carolina, and Georgia. Texas endangered: the gray bat, Indiana The paucity of monitoring data leads in the richness of mammals, bat, and Ozark and Virginia big- further inhibits their management. birds, and reptiles; North Carolina eared bats. Human disturbance leads in amphibian diversity. Texas to hibernation and maternity colonies dominates vertebrate richness by Introduction is a major factor in their decline. virtue of its large size and the variety of its ecosystems. ■ The South is the center of The biodiversity of the South is amphibian biodiversity in the ■ Loss of habitat is the primary impressive. Factors contributing to Nation. However, there are growing cause of endangerment of terrestrial that diversity include regional gradients concerns about amphibian declines. vertebrates. Forests, grasslands, in climate, geologic and edaphic site Potential causes include habitat shrublands, and wetlands have conditions, topographic variation, destruction, exotic species, water been converted to urban, industrial, natural disturbance processes, and pollution, ozone depletion leading and agricultural uses. -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania. -

Appendix D. Migratory Birds in South Florida

Appendix D. Migratory Birds in South Florida. FAMILY PELECANIDAE ORDER GAVIIFORMES Pelecanus erythrorhynchos, American White Pelican FAMILY GAVIIDAE Pelecanus occidentalis, Brown Pelican Gavia stellata, Red-throated loon FAMILY PHALACROCORACIDAE Gavia immer, Common loon Gavia pacifica, Pacific loon Phalacrocorax carbo, Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus, Double-crested Cormorant ORDER PODICIPEDIFORMES FAMILY ANHINGIDAE FAMILY PODICIPEDIDAE Anhinga anhinga, Anhinga Tachybaptus, Least Grebe Podilymbus podiceps, Pied-billed Grebe FAMILY FREGATIDAE Podiceps auritus, Horned Grebe Podiceps nigricollis, Eared Grebe Fregata magnificens, Magnificent Frigatebird ORDER PROCELLARIIFORMES ORDER CICONIIFORMES FAMILY PROCELLARIIDAE FAMILY ARDEIDAE Calonectris diomedea, Cory’s Shearwater Botaurus lentiginosus, American Bittern Puffinus gravis, Greater Shearwater Ixobrychus exilis, Least Bittern Puffinus griseus, Sooty Shearwater Ardea herodias, Great Blue Heron Puffinus puffinus, Manx Shearwater Casmerodius albus, Great Egret Puffinus lherminieri, Audubon’s Shearwater Egretta thula, Snowy Egret Egretta caerulea, Little Blue Heron FAMILY HYDROBATIDAE Egretta tricolor, Tricolored Heron Egretta rufescens, Reddish Egret Oceanites oceanicus, Wilson’s Storm-Petrel Bubulcus ibis, Cattle Egret Oceanodroma leucorhoa, Leach’s Storm-Petrel Butorides striatus, Green-backed Heron Oceanodroma castro, Band-rumped Storm-Petrel Nycticorax nycticorax, Black-crowned Night Heron Nycticorax violaceus, Yellow-crowned Night Heron ORDER PELECANIFORMES FAMILY THRESKIORNITHIDAE -

Habitat Distribution of Birds Wintering in Central Andros, the Bahamas: Implications for Management

Caribbean Journal of Science, Vol. 41, No. 1, 75-87, 2005 Copyright 2005 College of Arts and Sciences University of Puerto Rico, Mayagu¨ez Habitat Distribution of Birds Wintering in Central Andros, The Bahamas: Implications for Management DAVE CURRIE1,JOSEPH M. WUNDERLE JR.2,5,DAVID N. EWERT3,MATTHEW R. ANDERSON2, ANCILLENO DAVIS4, AND JASMINE TURNER4 1 Puerto Rico Conservation Foundation c/o International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, Sabana Field Research Station HC 0 Box 6205, Luquillo, Puerto Rico 00773, USA. 2 International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, Sabana Field Research Station HC 0 Box 6205, Luquillo, Puerto Rico 00773, USA. 3 The Nature Conservancy, 101 East Grand River, Lansing, MI 48906, USA. 4 The Bahamas National Trust, P.O. Box N-4105, Nassau, The Bahamas. 5 Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—We studied winter avian distribution in three representative pine-dominated habitats and three broadleaf habitats in an area recently designated as a National Park on Andros Island, The Bahamas, 1-23 February 2002. During 180 five-minute point counts, 1731 individuals were detected (1427 permanent residents and 304 winter residents) representing 51 species (29 permanent and 22 winter residents). Wood warblers (Family Parulidae) comprised the majority (81%) of winter residents. Total number of species and individuals (both winter and permanent residents) were generally highest in moderately disturbed pine- dominated habitats. The composition of winter bird communities differed between pine and broadleaf habitats; the extent of these differences was dependent broadleaf on composition and age in the pine understory. Fifteen bird species (nine permanent residents and six winter residents) exhibited significant habitat preferences. -

Conservación Checklist to the Birds of Colombia 2009

Número 8 • Mayo 2009 C Coonnsseerrvvaacciióónn CCoolloommbbiiaannaa tá • Colombia ISSN 1900-1592 ©2009 Fundación ProAves • Bogo ©2009 Fundación CChheecckklliisstt ttoo tthhee bbiirrddss ooff CCoolloommbbiiaa 22000099 LLiissttaaddoo ddee AAvveess ddee CCoolloommbbiiaa 22000099 Paul Salaman, Thomas Donegan & David Caro Conservacion Colombiana – Número 8 – Mayo 2009 1 Conservación Colombiana Journal for the diffusion of biodiversity conservation activities en Colombia. Revista de difusión de acciones de conservación de la biodiversidad en Colombia. ISSN 1900–1592. Non-profit entity no. S0022872 – Commercial Chamber of Bogotá ISSN 1900–1592. Entidad sin ánimo de lucro S0022872 – Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá. Conservación Colombiana Es una revista científica publicada por la Fundación ProAves, institución que tiene como misión «proteger las aves silvestres y sus hábitat en Colombia a través de la investigación, acciones de conservación puntuales y el acercamiento a la comunidad. El propósito de la revista es divulgar las acciones de conservación que se llevan a cabo en Colombia, para avanzar en su conocimiento y en las técnicas correspondientes. El formato y tipo de los manuscritos que se publican es variado, incluyendo reportes de las actividades de conservación desarrolladas, resultados de las investigaciones y el monitoreo de especies amenazadas, proyectos de grado de estudiantes universitarios, inventarios y conteos poblacionales, planes de acción o estrategias desarrolladas para especies particulares, sitios o regiones y avances en la expansión de la red de áreas protegidas en Colombia. Conservación Colombiana está dirigida a un público amplio, incluyendo científicos, conservacionistas y personas en general interesadas en la conservación de las especies amenazadas de Colombia y sus hábitats. Fundación ProAves Dirección: Carrera 20 No. -

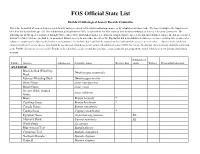

FOS Official State List

FOS Official State List Florida Ornithological Society Records Committee This is the formal list of modern bird species definitely having occurred in Florida by natural appearance or by establishment of an exotic. The base list shall be the Supplement: Checklist of Florida Birds, pp. 255-260 in Robertson & Woolfenden (1992), as updated by final decisions of the Florida Ornithological Society’s Records Committee. The following list of 525 species is updated through 31 December 2018. Established exotics (e); extinct or extirpated native species (x) and disestablished exotics (d); and species listed without verifiable evidence (u) shall be so annotated. Extinct species do not reduce the size of the Florida list, but a disestablished exotic species does. A distinctive member of a subspecies group may be added to the list for review purposes (see below), but it shall not be counted on the list beyond the species’ presence there. Species in the list below annotated with an *(review species list) should be documented when detected in Florida and submitted to the FOSRC for review. In addition, documentation should be submitted to the FOSRC for any species detected in Florida, believed to have occurred naturally or to have escaped, but not appearing in the main list below or in its formatted download versions. Established Family Species Subspecies Scientific name Review List exotic Extinct Disestablished exotic ANATIDAE Black-bellied Whistling- Dendrocygna autumnalis Duck Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Snow Goose Anser caerulescens -

Bird Checklist

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Everglades National Park Florida Bird Checklist Printed through the generosity of the Everglades Association. September 2005 Introduction Sp S F W Name B Sp S F W Loons Everglades National Park was established in 1947 to protect south Florida’s subtropical wetlands, particularly the diverse Red-throated Loon * and abundant birdlife. It’s difficult to imagine that the number Common Loon r r r of birds we see here today is only a small fraction of what once Grebes existed. Due to the widespread slaughter of wading birds for Pied-billed Grebe + c u c c their plumes in the early 1900s, and intense water management practices over the last 90 years, 90%-95% of the bird popula- Horned Grebe r r u tion has disappeared. Despite this tragic decline, birds continue Red-necked Grebe * * to be one of the park’s primary attractions. Eared Grebe * This checklist is a complete list of birds observed in the park, a Shearwaters & Petrels total of 366 species as of September 1, 2003. The key below in- Greater Shearwater * * dicates the seasonal occurrence and frequency of each species. Sooty Shearwater * * * The likelihood of observing a particular species is dependent upon being in the proper habitat during the correct season. Audubon’s Shearwater * Wilson’s Storm-Petrel * * This list reflects the continuing growth of information about Leach’s Storm-Petrel * the birds of the park and follows earlier checklists compiled by Boobies & Gannets Willard E. Dilley, William B. Robertson, Jr., Richard L. Cun- ningham, and John C. -

Breeding Biology and Natural History of the Bahama Swallow

Wilson Bull., 108(3), 1996, pp. 480-495 BREEDING BIOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY OF THE BAHAMA SWALLOW PAUL E. ALLEN ABSTRACT.-The Bahama Swallow (Tachycineta cyaneoviridis) is an obligate secondary cavity-nester endemic to the pine forests of four islands in the northern Bahamas. The near- threatened status of this poorly known species stems from the limited extent of pine forest breeding habitat, a history of logging in that habitat, and potential competition from exotic secondary cavity-nesters. Natural nest sites of Bahama Swallows on Grand Bahama gen- erally were abandoned woodpecker cavities and nests in all types of cavities were built from pine needles, Casuarina spp. twigs, and grass. Mean clutch size was 3.0 and the pure white eggs were slightly larger than those of Tree Swallows (T. bicolor). Both the mean incubation and nestling periods, 15.8 days and 22.7 days, respectively, were longer than those of Tree Swallows. Hatching success and nestling success were 87% and 81%, respectively, giving an overall success rate of 70%. One case of double-brooding was documented, and two other likely cases were noted. Weekly surveys of adults in pine forest habitat on Grand Bahama during breeding gave a linear density of 0.184.25 pairs-ktn’. The result from a single survey on Andros (0.21 pairs-km-‘) corresponds to survey results on Grand Bahama in the same period and very roughly agrees with the outcome of a 1988 survey. Received 13 October 1995, accepted I8 February 1996. The Bahama Swallow (Tuchycinetu cyaneoviridis), currently listed as near-threatened (Collar et al.