ARSC Journal, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Toscanini SSB Sib6

STAR SPANGLED MUSIC EDITIONS The Star-Spangled Banner for Orchestra (1943, revised 1951) Original Tune By JOHN STAFFORD SMITH Arranged and Orchestrated By ARTURO TOSCANINI Full Score Star Spangled Music Foundation www.starspangledmusic.org STAR SPANGLED MUSIC EDITIONS The Star-Spangled Banner for Orchestra (1943, revised 1951) Original Tune By JOHN STAFFORD SMITH Arranged and Orchestrated By ARTURO TOSCANINI 06/14/2014 Imprint Star Spangled Music Foundation www.starspangledmusic.org Star Spangled Music Editions Mark Clague, editor Performance materials available from the Star Spangled Music Foundation: www.starspangledmusic.org Published by the Star Spangled Music Foundation Musical arrangement © 1951 Estate of Arturo Toscanini, used by permission This edition © 2014 by the Star Spangled Music Foundation Ann Arbor, MI Printed in the U.S.A. Music Engraving: Michael-Thomas Foumai & Daniel Reed Editorial Assistance: Barbara Haws, Laura Jackson, Jacob Kimerer, and Gabe Smith COPYRIGHT NOTICE Toscanini’s arrangement of “The Star-Spangled Banner” is made in cooperation with the conductor’s heirs and the music remains copyrighted by the Estate of Arturo Toscanini ©1951. Prefatory texts and this edition are made available by the Star Spangled Music Foundation ©2014. SUPPORT STAR SPANGLED MUSIC EDITIONS This edition is offered free of charge for non-profit educational use and performance. Other permissions can be arranged through the Estate of Arturo Toscanini. We appreciate notice of your performances as it helps document our mission. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation to the Star Spangled Music Foundation to support this effort. The Star Spangled Music Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. -

The Politics of Verdi's Cantica

The Politics of Verdi’s Cantica The Politics of Verdi’s Cantica treats a singular case study of the use of music to resist oppression, combat evil, and fight injustice. Cantica, better known as Inno delle nazioni / Hymn of the Nations, commissioned from Italy’s foremost composer to represent the newly independent nation at the 1862 London International Exhibition, served as a national voice of pride and of protest for Italy across two centuries and in two very different political situations. The book unpacks, for the first time, the full history of Verdi’s composition from its creation, performance, and publication in the 1860s through its appropriation as purposeful social and political commentary and of its perception by American broadcast media as a ‘weapon of art’ in the mid twentieth century. Based on largely untapped primary archival and other documentary sources, journalistic writings, and radio and film scripts, the project discusses the changing meanings of the composition over time. It not only unravels the complex history of the work in the nineteenth century, of greater significance it offers the first fully documented study of the performances, radio broadcast, and filming of the work by the renowned Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini during World War II. In presenting new evidence about ways in which Verdi’s music was appropriated by expatriate Italians and the United States government for cross-cultural propaganda in America and in Italy, it addresses the intertwining of Italian and American culture with regard to art, politics, and history; and investigates the ways in which the press and broadcast media helped construct a musical weapon that traversed ethnic, aesthetic, and temporal boundaries to make a strong political statement. -

RCA Victor LCT 1 10 Inch “Collector's Series”

RCA Discography Part 28 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor LCT 1 10 Inch “Collector’s Series” The LCT series was releases in the Long Play format of material that was previously released only on 78 RPM records. The series was billed as the Collector’s Treasury Series. LCT 1 – Composers’ Favorite Intepretations - Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra [195?] Rosca: Recondita Amonia – Enrico Caruso/Madama Butterfly, Entrance of Butterfly – G. Farrar/Louise: Depuis Le Jour – M. Garden/Louise: Depuis Longtemps j’Habitais – E Johnson/Tosca: Vissi D’Arte – M. Jeritza/Der Rosenkavailier Da Geht ER Hin and Ich Werd Jetzt in Die Kirchen Geh’n – L Lehmann/Otello: Morte d’Otello – F. Tamagno LCT 2 – Caruso Sings Light Music – Enrico Caruso and Mischa Elman [195?] O Sole Mio/The Lost Chord/For You Alone/Ave Maria (Largo From "Xerxes")/Because/Élégie/Sei Morta Nella Vita Mia LCT 3 – Boris Goudnoff (Moussorgsky) – Feodor Chalipin, Albert Coates and Orchestra [1950] Coronation Scene/Ah, I Am Suffocating (Clock Scene)/I Have Attained The Highest Power/Prayer Of Boris/Death Of Boris LCT 4 LCT 5- Hamlet (Shakespeare) – Laurence Olivier with Philharmonia Orchestra [1950] O That This Too, Too Solid Flesh/Funeral March/To Be Or Not To Be/How Long Hast Thou Been Gravemaker/Speak The Speech/The Play Scene LCT 6 – Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 in G Minor Op. 63 (Prokofieff) – Jascha Heifetz and Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra [1950] LCT 7 – Haydn Symphony in G Major – Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra [195?] LCT 8 LCT 9 LCT 10 –Rosa Ponselle in Opera and Song – Rosa Ponselle [195?] La Vestale: Tu Che Invoco; O Nume Tutelar, By Spontini/Otello: Salce! Salce! (Willow Song); Ave Maria, By Verdi/Ave Maria, By Schubert/Home, Sweet Home, By Bishop LCT 11 – Sir Harry Lauder Favorites – Harry Lauder [195?] Romin' In The Gloamin'/Soosie Maclean/A Wee Deoch An' Doris/Breakfast In Bed On Sunday Morning/When I Met Mackay/Scotch Memories LCT 12 – Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. -

Toscanini VII, 1937-1942

Toscanini VII, 1937-1942: NBC, London, Netherlands, Lucerne, Buenos Aires, Philadelphia We now return to our regularly scheduled program, and with it will come my first detailed analyses of Toscanini’s style in various music because, for once, we have a number of complete performances by alternate orchestras to compare. This is paramount because it shows quite clear- ly that, although he had a uniform approach to music and insisted on both technical perfection and emotional commitment from his orchestras, he did not, as Stokowski or Furtwängler did, impose a specific sound on his orchestras. Although he insisted on uniform bowing in the case of the Philadelphia Orchestra, for instance, one can still discern the classic Philadelphia Orchestra sound, despite its being “neatened up” to meet his standards. In the case of the BBC Symphony, for instance, the sound he elicited from them was not far removed from the sound that Adrian Boult got out of them, in part because Boult himself preferred a lean, clean sound as did Tosca- nini. We shall also see that, for better or worse, the various guest conductors of the NBC Sym- phony Orchestra did not get vastly improved sound result out of them, not even that wizard of orchestral sound, Leopold Stokowki, because the sound profile of the orchestra was neither warm in timbre nor fluid in phrasing. Toscanini’s agreement to come back to New York to head an orchestra created (pretty much) for him is still shrouded in mystery. All we know for certain is that Samuel Chotzinoff, representing David Sarnoff and RCA, went to see him in Italy and made him the offer, and that he first turned it down. -

Eugene Ormandy Commercial Sound Recordings Ms

Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Ms. Coll. 410 Last updated on October 31, 2018. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2018 October 31 Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 - Page 2 - Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Summary Information Repository University of Pennsylvania: Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts Creator Ormandy, Eugene, 1899-1985 -

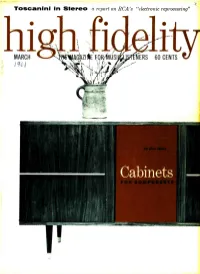

Toscanini in Stereo a Report on RCA's "Electronic Reprocessing"

Toscanini in Stereo a report on RCA's "electronic reprocessing" MARCH ERS 60 CENTS FOR STEREO FANS! Three immortal recordings by Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony have been given new tonal beauty and realism by means of a new RCA Victor engineering development, Electronic Stereo characteristics electronically, Reprocessing ( ESR ) . As a result of this technique, which creates stereo the Toscanini masterpieces emerge more moving, more impressive than ever before. With rigid supervision, all the artistic values have been scrupulously preserved. The performances are musically unaffected, but enhanced by the added spaciousness of ESR. Hear these historic Toscanini ESR albums at your dealer's soon. They cost no more than the original Toscanini monaural albums, which are still available. Note: ESR is for stereo phonographs only. A T ACTOR records, on the 33, newest idea in lei RACRO Or AMERICA Ask your dealer about Compact /1 CORPORATION M..00I sun.) . ., VINO .IMCMitmt Menem ILLCr sí1.10 ttitis I,M MT,oMC Mc0001.4 M , mi1MM MCRtmM M nm Simniind MOMSOMMC M Dvoìtk . Rn.psthI SYMPHONY Reemergáy Ravel RRntun. of Rome Plue. of Rome "FROM THE NEW WORLD" Pictures at an Exhibition TOSCANINI ARTURO TOSCANINI Toscanini NBC Symphony Orchestra Arturo It's all Empire -from the remarkable 208 belt- driven 3 -speed turntable -so quiet that only the sound of the music distinguishes between the turntable at rest and the turntable in motion ... to the famed Empire 98 transcription arm, so perfectly balanced that it will track a record with stylus forces well below those recommended by cartridge manufacturers. A. handsome matching walnut base is pro- vided. -

04-30-2019 Walkure Eve.Indd

RICHARD WAGNER der ring des nibelungen conductor Die Walküre Philippe Jordan Opera in three acts production Robert Lepage Libretto by the composer associate director Tuesday, April 30, 2019 Neilson Vignola 6:00–11:00 PM set designer Carl Fillion costume designer François St-Aubin lighting designer Etienne Boucher The production of Die Walküre was made video image artist possible by a generous gift from Ann Ziff and Boris Firquet the Ziff Family, in memory of William Ziff revival stage directors The revival of this production is made possible Gina Lapinski J. Knighten Smit by a gift from Ann Ziff general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin In collaboration with Ex Machina 2018–19 SEASON The 541st Metropolitan Opera performance of RICHARD WAGNER’S die walküre conductor Philippe Jordan in order of vocal appearance siegmund waltr aute Stuart Skelton Renée Tatum* sieglinde schwertleite Eva-Maria Westbroek Daryl Freedman hunding ortlinde Günther Groissböck Wendy Bryn Harmer* wotan siegrune Michael Volle Eve Gigliotti brünnhilde grimgerde Christine Goerke* Maya Lahyani frick a rossweisse Jamie Barton Mary Phillips gerhilde Kelly Cae Hogan helmwige Jessica Faselt** Tuesday, April 30, 2019, 6:00–11:00PM Musical Preparation Carol Isaac, Jonathan C. Kelly, Dimitri Dover*, and Marius Stieghorst Assistant Stage Directors Stephen Pickover and Paula Suozzi Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter German Coach Marianne Barrett Prompter Carol Isaac Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted -

Santa Barbara Music Club P.O

Upcoming Music Club Events Beethoven Birthday Celebration Saturday, December 13, 2003 at 3:00 PM In the Faulkner Gallery “Sonata in C-minor, op. 30, no. 2” Barbara Coventry, violin and Allen Bishop, piano “Sonata in A, op. 69” Ervin Klinkon, cello, and Allen Bishop, piano “Trio in D, op. 70, no. 1 (Ghost) Barbara Coventry, violin, Ervin Klinkon, cello, and Allen Bishop, piano ************************************************** Matinee Program at 3:00 PM Saturday, December 20, 2003 at the Faulkner Gallery Gabrielle Peng, Kimberly Peng, and Sheppard Peng, violins, with Beverly Staples, piano, Bach “Concerto for 3 Violins in D” and McLean “Tango for 3 Violins and Piano” MORNING PROGRAM Sarah Hodges, flute and Seungah Seo, piano, Poulenc “Sonata” Elaine Renner, cello, and Viva Knight, piano, Brahms “First Sonata in E-minor, op.38” Marian Drandell-Gilbert, piano, Bach “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” Albeniz “Cantos de España,” Debussy “Jardins sous la pluie” and Liszt, “La Campanella” Wednesday December 10, 2003 11:00 a.m. Membership Information: See the Music Club table by the entrance of the room, visit www.sbmusicclub.org or call Beverly Yellen at (805) 682-3462 The Unitarian Society 1535 Santa Barbara St. Santa Barbara Music Club P.O. Box 3974 Santa Barbara, California Santa Barbara, CA 93130 Notes on the Performers Morning Program Mahlon Balderston, organ, has a Bachelor of Music degree from Oberlin College Wednesday, December 10, 2003 at 11:00 a.m. and a Master of Arts degree from Iowa State University. He is Professor Emeritus The Unitarian Society, 1535 Santa Barbara St. of Santa Barbara City College, and is Music Director and organist at the Unitarian Society. -

Carnegie Hall

CARNEGIE HALL VICTOR DE SABATA 259-3-244-50 ALFRED SCOH PUBLISHER 156 FIFTH AVENUE. NEW YORK CARNEGIE HALL PROGRAM 3 CARNEGIE HALL ANNOUNCEMENTS RCA VICTOR RECORDING MARCH CHOPIN—Sonata in B-flat minor, Op. 35. Artur Rubinstein, Pianist. 24, Fri. 2:30 p.m.—The Philharmonic-Symphony So WDM-1082................. Price $3.51 ciety of New York An RCA Victor 45 r.p.m. release 24, Fri. 8:30 p.m.—Oratorio Societv LIBERTY MUSIC SHOPS SiSliSÄ iE: 25, Sat. 2:30 p.m.—Jose Torres, Spanish Dancer 25, Sat. 8:45 p.m.—The Philharmonic-Symphony So ciety of New York 26, Sun. 2:45 p.m.—The Philharmonic-Symphony So ciety of New York VISIT 26, Sun. 5:30 p.m.—Barbara Denenholz, Pianist. "Twi light Concert Series” 26, Sun. 8:30 p.m.—B’nai B’rith Victory Lodge No. CARNEGIE HALE’S OWN 1481. George Gershwin Memorial Concert 27, Mon. 8:30 p.m.—Jeanette Haien, Pianist GALLERY BAR AND 28, Tues. 8:30 p.m.—The Philadelphia Orchestra 29, Wed. 8:30 p.m.—League for Religious Labor in RESTAURANT Eretz Israel. Benefit Concert and All-Star show Before the Concert . 30, Thurs. 8:45 p.m.—The Philharmonic-Symphony So We serve the largest selection ciety of New York 31, Fri. 2:30 p.m.—The Philharmonic-Symphony So of liqueurs in townl ciety of New York After the Concert . Church of The Healing Christ — Dr. Emmet Fox, Pastor Services every Sunday morning and Wednesday noon Choice of Sandwich, Pastry and Coffee 75/ Luncheon served from One P.M. -

July 1946) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 7-1-1946 Volume 64, Number 07 (July 1946) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 64, Number 07 (July 1946)." , (1946). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/193 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PHOTO BY PHILIP ^ENDREAU, N. Y. mm . ! i-AYVRENCE TIBBETT, recently appeared for the first time on STUDY? Metropolitan Opera any operatic stage when she sang the TO Bass, and Robert Law- title role in “Carmen” with the New York SHALL I GO WHERE rence, former music City Opera Company. According to news- critic turned, conductor, paper accounts, she “made an instant and making joint con- are pronounced success . giving an im- York City) operatic^ ap- Private Teachers (New cert and personation of uncommon interest and pearances in Italy, fea- appeal.” (^JniroJucing a post war marvel of concerts HELEN ANDERSON turing in their DAVIS American com- Walt music world, completely revolutionizing HAROLD FREDERICK Concert Pianist Lawrence music by whitman’s elegy, “When Lilacs the piano, harmony Tibbett Tibbett is Last in the VOICE Interesting course— posers. -

Igan MELBOURNE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

The Uuivers ical Society .~I' . The Igan• Pre,en" MELBOURNE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WILLEM VAN OTTERLOO, Principal Conductor LEONARD DOMMETT, Concertmaster SATURDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 24, 1970, AT 8: 30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PRO G RAM In recognition of the 25th anniversary of the United Nations National Anthems: Star-Spangled Banner and God Save the Queen* God save our gracious Queen, Long Jive our noble Queen, God save the Queen. Send her victorious, Happy and glorious, Long to reign over us, God save the Queen. Sun Music III ("Anniversary Music") PETER SCULTHORPE Four Movements from the Symphonic Poem Psyche FRANCK Le Sommeil de Psyche Psyche enlevee par les Zephyrs Le Jardin d'Eros Psyche et Eros Hymn of the Nations VERDI SMALL CHORUS OF THE UNIVERSITY CHORAL UNION JOHN MCCOLLUM, Tenor DONALD BRYANT, Director INTERMISSION Symphony No.5 in C minor, Op. 67 BEETHOVEN Allegro can brio Andante can mota Scherzo: allegro Finale: allegro * University Choral Union leading the National Anthems Odyssey Records The M elbo llrne Symphony Orchestra is directed by the Australian Broadcasting Commission. Third Concert Ninety-second Annual Choral Union Series Complete Programs 3700 Hymn of the Nations VERDI (Text by Arrigo Boito) Arrigo Boito and Giuseppe Verdi together wrote two great masterpieces of Italian opera, Otello and Falstaff. It is of interest that the two men worked for the first time as a team, not on a composition for the theater but on a Cantata. Boito was only twenty years old when he wrote the text of "Inno delle Nazioni" ("Hymn of the Nations"), the cantata which Verdi submitted for performance at the London Exhibition of 1862.