Review of Mauritius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slope Disasters in Mauritius 4-5 115

Appendix 3.2.4 Effects of the constructed countermeasure works (evaluations) JICA Technical cooperation project: Landslide adviser for Mauritius (Final Report) Appendix 3.2.4 Effects of the constructed countermeasure works (evaluations) Existing slope countermeasures were found only in two sites of the total 18, and it was judged that those countermeasures were insufficient by MPI and JET. <Management No.2016-010, Maconde> This slope is located at the cape of Maconde on the south coast of the island. Most of the rock falls were from the basalt part of the cliff. In July and August 2014, RDA carried out removal works of rocks which were unstable and close to the road, and a new road (shift of alignment) was built to reduce the damage from rock falls. In addition, a retaining wall with a rockfall protection fence has been installed in one part of the site. However, it was judged that those countermeasures were insufficient. Rock falls and small rock failures are also a frequent occurrence along the new road because the rocks are weathered, and there is a high possibility of rock fall in future. Photo 1 Maconde (Management No.2016-010), 5 August 2016 (Source: JET) 1 JICA Technical cooperation project: Landslide adviser for Mauritius (Final Report) Appendix 3.2.4 <Management No. 2016-018, Hermitage> This site is situated in the vicinity of Grand River North West. As an existing countermeasure, a boundary wall was constructed by the land developer, but it had been already collapsed in 2012. In the future, a retaining wall should be installed there as a permanent countermeasure for the slope. -

Women, Slavery, and British Imperial Interventions in Mauritius, 1810–1845

Women, Slavery, and British Imperial Interventions in Mauritius, 1810–1845 Tyler Yank Department of History and Classical Studies Faculty of Arts McGill University, Montréal October 2019 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Tyler Yank 2019 ` Table of Contents ! Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Résumé ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Figures ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 10 History & Historiography ............................................................................................................. 15 Definitions ..................................................................................................................................... 21 Scope of Study ............................................................................................................................. -

Draft the District Council of Grand Port

ANNUAL REPORT JULY 2016- JUNE 2017 (Under Section 142 of the Local Government Act 2011, as subsequently amended 1 | P a g e CONTENTS 1.0 Mission, Vision and Value Statement Page 5 2.0 Information on The District Council of Grand Port Page 6 3.0 Roles and function of Committees Page 12 4.0 Trends and Challenges Page 32 5.0 Major Achievements for period July 2016 – June 2017 Page 35 6.0 Financial Statements for year 2016/2017 Page 38 7.0 Comparison of budget with actual for year 2016/2017 Page 46 8.0 Strategic Direction Page 53 2 | P a g e Chief Executive’s Statement Pursuant to Section 142 of the Local Government Act 2011 as subsequently amended, I have much pleasure to submit the Annual Report for the period January– June 2016 for the District Council of Grand Port. I am thankful to the staff for having put their level best to ensure the materialisation of our goals, aims and objectives during the year. My team has seen to it that Council’s decisions be forthwith implemented to the satisfaction of all our stakeholders whilst being in compliance with our statutory duties and legal requirements. This report highlights our main achievements for .July 2016 – June 2017 and indicates our objectives for July 2017 – June 2018 S. TEELUCK CHIEF EXECUTIVE 3 | P a g e Chairperson’s Statement Since my election as Chairperson on 21st December 2016, I have pursued the goals and objectives of the Council and seen to it that same be implemented to the satisfaction of all stakeholders at all times. -

Draft the District Council of Grand Port

ANNUAL REPORT JULY 2017- JUNE 2018 (Under Section 142 of the Local Government Act 2011, as subsequently amended 1 | P a g e CONTENTS 1.0 Mission, Vision and Value Statement Page 5 2.0 Information on The District Council of Grand Port Page 6 3.0 Roles and function of Committees Page 12 4.0 Trends and Challenges Page 32 5.0 Major Achievements for period July 2017 – June 2018 Page 35 6.0 Financial Statements for year 2017/2018 Page 38 7.0 Comparison of budget with actual for year 2017/2018 Page 46 8.0 Strategic Direction Page 53 2 | P a g e Chief Executive’s Statement Pursuant to Section 142 of the Local Government Act 2011 as subsequently amended, I have much pleasure to submit the Annual Report for the period January– June 2016 for the District Council of Grand Port. I am thankful to the staff for having put their level best to ensure the materialisation of our goals, aims and objectives during the year. My team has seen to it that Council’s decisions be forthwith implemented to the satisfaction of all our stakeholders whilst being in compliance with our statutory duties and legal requirements. This report highlights our main achievements for .July 2017 – June 2018. S. TEELUCK CHIEF EXECUTIVE 3 | P a g e Chairperson’s Statement Since my election as Chairperson on 21st December 2016, I have pursued the goals and objectives of the Council and seen to it that same be implemented to the satisfaction of all stakeholders at all times. -

Sitting of Tuesday 04 June 2013

PARLIAMENTARY QUESTIONS PAGE 1 of 18 MAURITIUS NATIONAL ASSEMBLY Questions of which notice has been given Requiring an Oral Answer Sitting of Tuesday 04 June 2013 Questions addressed to Dr the Honourable Prime Minister, Minister of Defence, Home Affairs and External Communications, Minister for Rodrigues B/410 The Honourable First Member for Mahebourg and Plaine Magnien (Mr Jhugroo) To ask Dr the Honourable Prime Minister, Minister of Defence, Home Affairs and External Communications, Minister for Rodrigues:- Whether, in regard to capital punishment, he will state if consideration will be given for the re-introduction thereof with a view to combatting cases of atrocious murders/manslaughters and, if not, why not? B/411 The Honourable First Member for Mahebourg and Plaine Magnien (Mr Jhugroo) To ask Dr the Honourable Prime Minister, Minister of Defence, Home Affairs and External Communications, Minister for Rodrigues:- Whether, in regard to the recent fatal road accident which occurred at Sorèze, on 3 May 2013, he will, for the benefit of the House, obtain from the Commissioner of Police, information as to where matters stand as to the inquiries carried out thereinto? B/412 The Honourable Second Member for Curepipe and Midlands (Dr Boolell) To ask Dr the Honourable Prime Minister, Minister of Defence, Home Affairs and External Communications, Minister for Rodrigues:- Whether, in regard to the driving licence, he will, for the benefit of the House, obtain from the Commissioner of Police, information as to the criteria considered for the -

Blue Bay Marine Park Management Plan

UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY PROJECT NO. MAR/03/G35/A/1G/99 BLUE BAY MARINE PARK MANAGEMENT PLAN MINISTRY OF FISHERIES & RODRIGUES REPUBLIC OF MAURITIUS SEP TEMBE R 2012 Blue Bay Marine Park 1 Management Plan BLUE BAY MARINE PARK MANAGEMENT PLAN ANNEX Blue Bay Marine Park (southern area): La Cambuse and Le Chaland Blue Bay Marine Park 97 Management Plan BLUE BAY MARINE PARK MANAGEMENT PLAN APPENDIX A PARTICIPATORY PROCESS AND SWOT ANALYSIS Blue Bay Marine Park 98 Management Plan APPENDIX A BLUE BAY MARINE PARK MANAGEMENT PLAN PARTICIPATORY PROCESS AND SWOT ANALYSIS The Partnerships for Marine Protected Areas in Mauritius and Rodrigues Project (GoM, RRA, UNDP, GEF) was designed to foster sustainable use and equitable sharing of benefits from MPAs through broad based participation of stakeholders. The Project was designed as a demonstration to allow for the development of policies, institutional frameworks and co-management arrangements at three MPAs in Mauritius (Blue Bay, Balaclava and SEMPA). The vision of the project aimed toward a functioning co-managed MPA at SEMPA on Rodrigues and, based on lessons derived from this pilot, inform MPA management for the whole of Mauritius, including Blue Bay & Balaclava Marine Parks. Specific objectives of the Project were to: (i) develop an enabling policy and institutional framework for sustainably co-managed MPAs Formatted: Indent: Left: 0.25", Hanging: 0.25", Numbered throughout the Republic of Mauritius + Level: 1 + Numbering Style: i, ii, iii, … + Start at: 1 + Alignment: Left + Aligned at: 0.25" + Tab after: 0.75" + (ii) develop innovative co-management arrangements for MPAs and adapt them at a Indent at: 0.75", Tab stops: 0.5", List tab + Not at 0.75" representative demonstration site in Rodrigues. -

World Bank Document

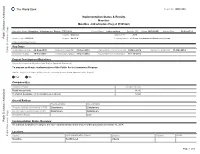

The World Bank Report No: ISR16800 Implementation Status & Results Mauritius Mauritius - Infrastructure Project (P091828) Operation Name: Mauritius - Infrastructure Project (P091828) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 12 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 26-Nov-2014 Country: Mauritius Approval FY: 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Sector Investment and Maintenance Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 24-Sep-2009 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2014 Planned Mid Term Review Date 30-Nov-2012 Last Archived ISR Date 17-Mar-2014 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 19-Feb-2010 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date 16-Feb-2013 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) To prepare and begin implementation of the Public Sector Investment Program Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Road Investments 36.10 Technical Assistance in the Infrastructure Sector 14.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Public Disclosure Authorized Implementation Status Overview All activities funded by the project are now complete ahead of the closure of the project on December 31, 2014. Locations Public Disclosure Copy Country -

Annual Report July 2018 – June 2019

ANNUAL REPORT JULY 2018- JUNE 2019 (Under Section 142 of the Local Government Act 2011, as subsequently amended 1 CONTENTS 1.0 Mission, Vision and Value Statement Page 6 2.0 Information on The District Council of Grand Port Page 7 3.0 Roles and function of Committees Page 13 4.0 Trends and Challenges Page 46 5.0 Disaster Management at the Council Page 49 6.0 Major Achievements for period July 2018 – June 2019 Page 53 7.0 Financial Statements for year 2018/2019 Page 56 8.0 Internal Audit Report Page 104 9.0 Audit Committee Report Page 105 2 Chief Executive’s Statement Pursuant to Section 134 (A) of the Local Government Act 2011 as subsequently amended, I have much pleasure to submit the Annual Report for the District Council of Grand Port for the financial year 2018/2019. I am thankful to my dedicated, loyal and committed personnel for having spared much effort to ensure that policy decisions taken by the Council be implemented in a timely and transparent way. The administration has also ensured that goals, objectives and strategies put on place be forthwith implemented to the satisfaction of all stakeholders whilst ensuring full compliance to our statutory duties and all legal requirements. I must also underline that the Council has received funding of Rs 99 million from the National Development Unit and Rs 30 million from the Ministry of Local Government and Outer Islands during the current financial year for implementation of infrastructural projects within our area. This report highlights our main achievements for July 2018 – June 2019 and indicates our strategic direction for the following three financial years. -

Communique Filing of Return & Payment of Income Tax

: 2076000 Fax: 2118099 : [email protected] COMMUNIQUE FILING OF RETURN & PAYMENT OF INCOME TAX 1. The due date for the submission of income tax return and payment of tax for the year of assessment 2008/2009 by individuals is Tuesday 30th September 2008. 2. The due date for submission of income tax return by companies, non resident societes, trusts and trustees of unit trust schemes whose accounting year ended between 01 July 2007 and 31 December 2007, should file the annual return for the year of assessment 2008-2009 on or before 30 September 2008. 3. Income Tax returns and payments, if any, should reach MRA office not later than 30th September 2008. In case of non-submission of return a penalty of Rs 2,000 per month up to a maximum penalty of Rs 20,000 will be applicable. In addition, a penalty of 5 % of the amount of tax remaining unpaid together with interest at the rate of 1 % per month will accrue. 4. In order to facilitate taxpayers for the filing of their returns and payment of income tax the MRA has scheduled the operation of its cash offices as follows: (a) 6 regional cash offices will be opened on 25th, 26th, 29th and 30th September 2008 from 09h00 to 14h30 at the following premises: Region Cash Office 1 Rose Hill NPF Building/Social Security House Moka Road, Rose Hill Wastewater Management Authority 2 Curepipe Curepipe Sub-Office 3 Pamplemousses Pamplemousses District Court 4 Flacq Flacq District Court 5 Mahebourg Mahebourg Social Security office 6 Souillac Souillac District Court (b) Cash counters at Ehram Court, Cnr. -

THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE of MAURITIUS Published by Authority

THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF MAURITIUS Published by Authority No. 103 - Port Louis : Saturday 26 November 2016 - Rs. 25.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL NOTICES 1755 — Special Legal Supplement 1756 — Legal Supplement 1757 j to ? Notice under the Land Acquisition Act 1762 ) 1763 — Post Declared Vacant 1764 1 to ? Declaration of Vacancy 1766 ' Police Notice - Whole Night Concert - Festival International Kreol at Neo Town, Les Salines on 26th and 27th November 2016 1768 — Police Notice - Messe re. Cardinalat Marie Reine de La Paix on Sunday 27th November 2016 1769 — Notice under Section 56(3)(a) of the Prevention of Corruption Act 2002 (PoCA 2002) 1770 — Sale by Authority of Justice 1771 — Consumer Price Index 1772 1 to ( Revocation of Freezing Order made under Section 45(1) of the Dangerous Drugs Act 2000 1774 ‘ 1775 — Notice under the Insolvency Act 1776 1 to ? Declaration of Draft Mauritian Standards 1777 ) 1778 1 to ? Notice under the Companies Act 1785 ) 1786 — Notice under the National Transport Authority 1787 1 to ? Notice under the Patents, Industrial Designs & Trademarks Act 1788 J SPECIAL LEGAL SUPPLEMENT See General Notice No. 1755 LEGAL SUPPLEMENT See General Notice No. 1756 4636 The Mauritius Government Gazette General Notice No. 1755 of 2016 The State Lands (Amendment of Schedule) Regulations 2016. SPECIAL LEGAL SUPPLEMENT (Government Notice No. 246 of 2016) The undermentioned Bills are published in the Special Legal Supplement to this number of the The Rodrigues Consumer Protection (Control Government Gazette: of Price of Taxable and Non-Taxable Goods) (Amendment No. 29) Regulations 2016. A Bill “To repeal the Co-operatives Act and replace it by a new enactment”. -

Application Under the National Regeneration Programme (Nrp) for the Village of Mahebourg

VISIO ARCHITECTURE LTD 45, St Georges Street Port-Louis, Mauritius T: + 230 208 93 94 T: + 230 210 40 73 E: [email protected] NRP APPLICATION / MAHEBOURG APPLICATION UNDER THE NATIONAL REGENERATION PROGRAMME (NRP) FOR THE VILLAGE OF MAHEBOURG SEP 2020 Page 1 of 23 VISIO ARCHITECTURE LTD 45, St Georges Street Port-Louis, Mauritius T: + 230 208 93 94 T: + 230 210 40 73 E: [email protected] NRP APPLICATION / MAHEBOURG TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE................................................................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION -THE CASE FOR URBAN REGENERATION .................................................................................. 3 2.1 THE IMPACTS OF COVID-19 .......................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 THE WAKASHIO INCIDENT ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. CONTEXT OPPORTUNITY APPRAISAL .................................................................................................................. 8 3.1 THE PROXIMITY OF THE AIRPORT AS A LOST OPPORTUNITY ....................................................................... 8 4. OVERVIEW OF MAHEBOURG .............................................................................................................................. 9 5. OVERVIEW OF THE PROPOSED BOUNDARY .................................................................................................... -

MAURITIUS Chamouny Main Dam Baie Du Chemin Or Waterway Cap Grenier Souillac TRAVEL GUIDE MAURITIUS Citrons River

8TH Ed TRAVEL GUIDE LEGEND INDIAN Grand OCEAN Baie Île d’Ambre Area Maps PORT Motorway LOUIS National Road Main Road Trou d’Eau Douce Minor Road Scenic Route Curepipe Track Provincial Mahébourg Boundary MAURITIUS Chamouny Main Dam Baie du Chemin or Waterway Cap Grenier Souillac TRAVEL GUIDE GUIDE TRAVEL Citrons River Waterfall CONTENTS Reef Practical, informative and user-friendly, the 1. Introducing Mauritius Mountain Globetrotter Travel Guide to Mauritius VACOAS MTS The Land Highlands highlights the major places of interest, describing their History in Brief principal attractions and offering sound suggestions Government and Economy Piton Savanne Peak in The People 704 m metres on where to tour, stay, eat, shop and relax. 2. The North Cabinet Nature NR Reserve THE AUTHOR The Northwest Coast PORT Rivière du Rempart Coast City Martine Maurel is a Mauritius-born French graduate, The Northern Offshore Islands LOUIS who spent some years living in Malawi. She has St Felix Town & Village 3. The East Coast and Rodrigues written a number of travel articles and books Place of The Flacq Coast Art Gallery Interest which have been very well received, including Visitor’s Northern Grand Port Coast Airport Mahébourg and Environs Guide to Malawi and Visitor’s Guide to Zimbabwe. Rodrigues Town Plans She has since returned to her native Mauritius, 4. The South and Southwest from where she still writes. Royal Road Main Road Savanne Coastal Belt MAURITIUS Le Morne Peninsula La Paix Other Road MAURITIUS Plaine Champagne Built-up 5. The West Coast Area Petite and Grande Rivière Noire Line Building of Barracks Interest Vital tips for visitors Tamarin Bay to Flic en Flac Published and distributed by Distributed in Africa by Distributed in the USA by South of Port Louis Place of New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd Map Studio The Globe Pequot Press Worship Best places to stay, eat and shop 6.