Ecocritical Perspective on Waverley and Tess of the D'urbervilles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wye Valley Management Plan 2015 to 2020

Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) Post- SEA & HRA Management Plan 2015-2020 December 2015 Wye Valley AONB Office Hadnock Road Monmouth NP25 3NG Wye Valley AONB Management Plan 2015-2020 Map 1: Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) Boundary Declaration Wye Valley AONB Management Plan 2015-2020 This Management Plan was produced and adopted by the Wye Valley AONB Joint Advisory Committee on behalf of the four local authorities, under the Countryside and Rights of Way (CRoW) Act 2000: Councillor Phil Cutter (signature) Chairman Wye Valley AONB JAC Councillor (signature) Cabinet Member for the Environment, Forest of Dean District Council (signature) Nigel Riglar Commissioning Director – Communities and Infrastructure, Gloucestershire County Council Councillor (signature) Cabinet Member, Economic Development and Community Services, Herefordshire Council Councillor (signature) Cabinet Member, Environment, Public Services & Housing, Monmouthshire County Council (signature) Regional Director, Natural England (West Mercia) (signature) Regional Director South and East Region, Natural Resources Wales Wye Valley AONB Management Plan 2015-2020 CONTENTS Map 1: Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) Foreword Declaration Part 1 Context ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose of the AONB Management Plan -

Wye Valley and Forest of Dean

UK Tentative List of Potential Sites for World Heritage Nomination: Application form Please save the application to your computer, fill in and email to: [email protected] The application form should be completed using the boxes provided under each question, and, where possible, within the word limit indicated. Please read the Information Sheets before completing the application form. It is also essential to refer to the accompanying Guidance Note for help with each question, and to the relevant paragraphs of UNESCO’s Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, (OG) available at: http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines Applicants should provide only the information requested at this stage. Further information may be sought in due course. (1) Name of Proposed World Heritage Site Wye Valley and Forest of Dean (2) Geographical Location Name of country/region England and Wales border & West Midlands / South West England border Grid reference to centre of site 3552 2095 Please enclose a map preferably A4-size, a plan of the site, and 6 photographs, preferably electronically. page 1 (3) Type of Site Please indicate category: Natural Cultural Mixed Cultural Landscape (4) Description Please provide a brief description of the proposed site, including the physical characteristics. 200 words The limestone plateau of the Forest of Dean and the adjacent gorge of the Wye Valley became the crucible of the industrial revolution and the birthplace of landscape conservation. The area has a full sequence of the Carboniferous Limestone Series and excellent exposures and formations including limestone pavement, caves, natural stream channels and tufa dams, alongside the deeply incised meanders of the River Wye and one of the largest concentrations of ancient woodland in Britain. -

Transactions Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club Volume 54 2006

TRANSACTIONS OF THE WOOLHOPE NATURALISTS’ FIELD CLUB HEREFORDSHIRE "HOPE ON" "HOPE EVER" ESTABLISHED 1851 VOLUME 54 2006 Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club 2006 ©2007 All contributions to The Woolhope Transactions are COPYRIGHT. None of them may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the writers. Applications to reproduce contributions, in whole or in part, should be addressed, in the first instance, to the current editor: Mrs. R. A. Lowe, Charlton, Goodrich, Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, HR9 6JF. The Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club is not responsible for any statement made, or opinion expressed, in these Transactions; the authors alone are responsible for their own papers and reports. Registered Charity No. 521000 website: www.woolhopeclub.org.uk TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Officers, 2006/2007 ......................................................................................................... 1 Obituary - Dr. Frank W. Pexton .................................................................................................. 2 Proceedings, 2006 ....................................................................................................................... 3 Accounts, 2006 ......................................................................................................................... 12 Biographical Details of Contributors ....................................................................................... -

English Landscape: the Picturesque

25 October 2017 English Landscape: The Picturesque PROFESSOR MALCOLM ANDREWS A century ago this was the popular image of England, perhaps even of Britain. The landscape is stylized and distilled into simple components: rolling hills, worn smooth to make pasture and arable land accommodating for livestock and plough; fields neatly partitioned by hedgerows of uneven growth; cottages nestling in the folds and embowered by larger trees. Formal affinities link the various natural and man-made components. Thus the softly rounded thatch roofs echo the rolling contours of the hills, and the sheltering trees billow gently like the clouds above. All is harmony. There’s just one human figure, the woman in the garden. But she is enough to strike the keynote: in effect the whole landscape is feminized, with the cottage homes embosomed in the soft curves of the domesticated landscape. Where are the menfolk? Here they are: Theirs is now the responsibility to protect this precious national state, written so eloquently into the landscape imagery. ‘Your country’s call’: does that mean your home countryside, or your country England? The ambiguity is highly charged. ‘To me, England is the country, and the country is England’, said Stanley Baldwin in 1924. (Speech to The Royal Society of St George, 6 May 1924). By the time of the First World War this image of thatched cottages, hedgerows and patchwork fields could be iconized to denote the national identity. The ensemble is essentially drawn from the countryside imagery of southern England, but it is made to stand for the whole country. By the beginning of the twentieth century the concept of ‘South Country’ -- mainly Kent, Surrey, Sussex and Hampshire -- had become very potent as a representation of the heart of England. -

Visit Monmouthshire Destination Management Activity Update – 18 March 2020

VISIT MONMOUTHSHIRE DESTINATION MANAGEMENT ACTIVITY UPDATE – 18 MARCH 2020 Strategy Monmouthshire’s Destination Management Plan 2017-2020 is due for revision at the end of 2020. Development of consultation process and timetable to be discussed and agreed with DMP members at meeting on 24th March. (Now postponed). Feedback provided on Monmouthshire’s Draft Cycling Strategy. Research Beaufort Research commissioned to undertake 2019 Monmouthshire Visitor Survey as part of 2019 pan Wales visitor survey – results will be presented at DMP meeting on 24 March 2020. (Now postponed – report attached). 2019 Monmouthshire Bedstock Survey underway – Visit Wales contributing 50% of salary costs. Participation in Wales Airbnb pilot study to estimate value of Airbnb accommodation to Monmouthshire’s visitor economy. Final report received. An online survey is now being carried out to identify the percentage of known accommodation businesses which use peer- to-peer websites to market their accommodation, and what percentage of their bookings are achieved that way. The link to the survey is here: https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/M2QRM8K Collation of visitor figures for 2019 Monmouthshire STEAM underway. Will be sent to Global Tourism Solutions for preparation of 2019 STEAM figures as soon as bedstock survey complete. Results due May / June 2020. Gwent Levels Accommodation Study and Gwent Levels Visitor Accommodation Advisory Pack available for download. 2020 serviced accommodation occupancy received (-4.6% Jan, -4.1% Feb compared with Jan / Feb 2019) Visitor Information Sharing space with One Stop Shop staff in old rent office currently. Will move back to One Stop Shop office when refurbishment of this office is complete, before finally moving back to old rent office in shared space with Borough Theatre when refurbishment of this office complete. -

105. Forest of Dean and Lower Wye Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 105. Forest of Dean and Lower Wye Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 105. Forest of Dean and Lower Wye Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform theirdecision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The informationthey contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. 1 The Natural Choice: Securing the Value of Nature, Defra NCA profiles are working documents which draw on current evidence and (2011; URL: www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm80/8082/8082.pdf) 2 knowledge. -

DC Research Report Template

Assessment of the impact of the Heritage Lottery Fund Collecting Cultures Initiative Annex 3: Case Studies Carlisle Leicester Suite 7 (Second Floor) 1 Hewett Close Carlyle’s Court Great Glen 1 St Mary’s Gate Leicester Carlisle CA3 8RY LE8 9DW t: 01228 402320 t: 0116 259 2390 m: 07501 725 114 m: 07501 725115 e: [email protected] e: [email protected] www.dcresearch.co.uk Assessment of the impact of the Heritage Lottery Fund Collecting Cultures Initiative CONTENTS Buxton Museum & Art Gallery, Derby Museums & Art Gallery and Belper North Mill: Enlightenment! Derbyshire Setting the Pace in the Eighteenth Century ........................ 1 Chepstow Museum, Monmouth Museum: The Wye Tour ............................................. 4 Crafts Study Centre: Developing a National Collection of Modern Crafts ....................... 6 Edinburgh University Collection of Musical Instruments: Enriching our Musical Heritage . 9 Fermanagh County Museum, Derry Heritage and Museum Service, Inniskillings Regimental Museum: Connection and Division ........................................................ 13 Gallery Oldham, The Harris Museum and Art Gallery: The Potters Art in the 20th Century ....................................................................... 16 The Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry, and Wolverhampton Art Gallery: Peace and Reconciliation ............................................................................................... 22 Jurassic Coast Museums Partnership: Jurassic Life Initiative .................................... -

Social Breaks V10.Indd

Social Breaks 2021-22 GUIDE & Holidays GROUP BREAKS ORGANISED BY MEMBERS, FOR MEMBERS YOUR 2021-2022 BREAKS 2021 AUGUST 23 – 27 Derbyshire by Design p6 SEPTEMBER 3 – 6 Scenic Snowdonia Fully Booked; see 2022 break on p34 10 – 13 Kynren, an Epic Tale of England p8 24 – 26 Bletchley Park and the City of Cambridge p10 OCTOBER 1 – 4 Cheltenham Chase Hotel Autumn Break p12 17 – 21 The Beautiful Lake District p14 NOVEMBER 29 Nov – 3 Dec Potters Midweek Festival Break p16 2022 MARCH 18 – 20 Oxford, City of Dreaming Spires p18 APRIL 25 – 29 Historic Chester NEW p20 MAY 2 – 6 Springtime in Bournemouth p22 11 – 13 Elegant Harrogate NEW p24 26 – 30 The Beautiful Lake District p26 JUNE 6 – 10 South Devon and the English Riviera p28 10 – 12 Windsor and the Royal Castle p30 27 Jun – 1 July Lovely Llandrindod, Heart of Wales p32 AUGUST 1 – 5 The Royal Victoria Hotel, Snowdonia p34 14 – 18 The Abbey Hotel, Great Malvern p36 SEPTEMBER 12 – 16 Blissful Bournemouth NEW p38 To find out more and see any new breaks and getaways that are added through the year, make sure you check out boundless.co.uk/social YOUR 2021-2022 BREAKS Welcome! We’re pleased to be able bring you our latest guide, featuring a host of fantastic breaks to fill your 2021/22 calendar. There’s something for everyone so we’re sure that you’ll find something to interest you. For the latest updates and to keep an eye on what new breaks we’re adding, visit our website regularly at boundless.co.uk/social We hope to meet you on one of our breaks soon. -

Monmouthshire Group Travel Guide

Monmouthshire Group Travel Guide Blaenau Gwent Blaenavon Bridgend Caerphilly Cardiff Merthyr Tydfil Monmouthshire www.visitsouthernwales.org Newport Rhondda Cynon Taf Vale of Glamorgan Monmouthshire is the Food Capital of Wales and we have a smorgasbord of award-winning Contents food and drink attractions and culinary courses. Ancre Hill Vineyard, Silver Circle Distillery, Humble by Nature, Monmouth. NP25 5HS Catbrook. NP16 6UL. Nr Monmouth. NP25 4RP Go on a guided tour, eat a Welsh cheese platter Meet the producers of Wye Valley Gin, find Based on a working farm in the Wye Valley. lunch or stay at our on-site accommodation. out how the gin is made and the locally Offers: Cookery, foraging & rural skills 04 06 Offers: Accommodation, Vineyard Tours, foraged botanicals that go into it classes, private dining. Gift Shop, Tastings Offers: Distillery tours and tastings, Distil www.humblebynature.com 01600 714152 your own gin courses [email protected] www.ancrehillestates.co.uk www.silvercircledistillery.com [email protected] [email protected] The Abergavenny Baker, Abergavenny. NP7 7PE Regional Overview Attractions Apple County Cider Co, Sugarloaf Vineyards, In her one day classes, baker Rachael near Skenfrith. NP25 5NS. Abergavenny. NP7 7LA Watson shares her knowledge, skill Taste award winning ciders with Ben This picturesque vineyard nestles amongst & enthusiasm for baking beautiful & buy homemade jams, cordials, local the rolling Welsh hills above Abergavenny. breads from around the world. ales, honey & ice creams. Offers: Accommodation, Vineyard Tours, www.abergavennybaker.co.uk Offers: Tastings, shop, catering. Gift Shop, Tastings [email protected] www.applecountycider.co.uk www.sugarloafvineyard.co.uk 08 10 12 [email protected] [email protected] The Preservation Society, Chepstow. -

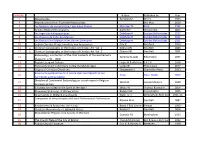

WAS Library May 2018

WAS No. Author Published by Year 1 About books . Berkeley M W.A.S. 1903 4 Reproductions from illustrated Manuscripts Brit Mus 1910 5 Les Religions de la prehistoire, l'age paleolithique Mainage Th Paris 1921 6 Ancient Biblical Chronograms . Black WH Chrono Inst 1865 7 Les Legendes haliographiques Delehaye H Soc des Bollandistes 1927 8 Les Origines de Culte des Martyrs Delehaye H Soc des Bollandistes 1912 9 Les Passions des Martyrs et les Genres Litteraires Delehaye H Soc des Bollandistes 1921 10 English Church Fittings, Furniture and Accessories Cox JC Batsford 1923 11 a Christian Iconography or the history of Christan Art Vol. 1 Didron AN Geo Bell 1886 11 b Christian Iconography or the history of Christan Art Vol. 2 Didron AN Geo Bell 1891 Ecclesiology; a collection of the chief contents of the Gentleman's 12 Gomme GL (ed) Elliot Stock 1894 Magazine 1731 - 1868 13 English Liturgical Colours Hope W & Atchley E S P C K 1918 14 Ecclesiastical Art in Germany during the Middle Ages Lubke W Thos C Jack 1877 15 Origins of Christian Church Art Strzygowski J Clarendon Press 1923 Essai sur le symbolisme de la cloche dans ses rapports et ses 16 Anon Henri Oudin 1859 harmonies avec la religion. Sketches of Continental Ecclesiology or church notes in Belgium 17 Webb B Joseph Masters 1848 Germany & Italy 18 Is Symbolism suited to the Spirit of the Age ? White W Thomas Bosworth 1854 20 Monumental Brasses of Warwickshire Badger EW Cornish Bros 1895 21 Gravestones in Midland churchyards Blake J E H Birmingham Arch Soc 1925-26 Companion to the principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture 22 Bloxam M H Geo Bell 1882 23 Roodscreens & Rood lofts. -

& the Wye Valley

& The Wye Valley stay / explore / experience www.visitherefordshire.co.uk Bringing the very best cinema to Herefordshire, Shropshire, Worcestershire and the Marches FRIDAY 23 FEBRUARY TO SUNDAY 11 MARCH BORDERLINES FILM FESTIVAL 2018 borderlinesfilmfestival.org @borderlines #borderlines2018 Zama FUNDERS PARTNERS stay / explore / experience erefordshire’s rich history in Plan your visit at Hfarming and cider production www.visitherefordshire.co.uk where makes it a county full of stunning you will find more information on landscapes, not least with the River places to stay, things to do, events and Wye meandering its way through the much more. county before making its way back Hereford also hosts a unique event into Wales. A visit to Herefordshire in 2018 with the Weeping Window could see you visiting castles, poppy display at Hereford Cathedral canoeing on the river, hiking up hills, from 14th March to 29th April – the walking the orchards, or simply taking last chance to see this as 2018 marks in village life with a chilled cider! the 100th anniversary of World War One, and the poppies will no longer Festivals & events, markets, local food be displayed in public after this. and drink producers are in abundance, This is a year of anniversaries as it as this really is a ‘home-grown’ county. also marks the 20th for the family The welcome you will receive will friendly Nozstock music festival make your trip as memorable as the near Bromyard, as well as the same landmark for Hereford’s theatre, The sights you will see. Courtyard Centre for the Arts. As if this wasn’t enough the world famous Three Choirs Festival also returns to visitherefordshire.co.uk the county from 28th July. -

& the Wye Valley

& The Wye Valley stay / explore / experience / 2019 www.visitherefordshire.co.uk A GREAT DAY OUT AT WESTONS CIDER MILL find out how we make our award-winning ciders with a tour and tasting experience Daily tours at: 11.00am, 12.30pm, 2.00pm and 3.30pm Cider Shop | Restaurant & Tea Room | Free Parking | Open 7 days a week | Children’s Play Park CALL 01531 660108 FOR MORE INFORMATION MUCH MARCLE, LEDBURY, HEREFORDSHIRE, HR8 2NQ [email protected] SO MUCH MORE IN EVERY DROP Westons-Cider.co.uk Visit Herefordshire_VC_2626.indd 1 21/08/2018 14:17 stay / explore / experience erefordshire’s rich history in May during the Big Apple Blossomtime, Hfarming and cider production international literary figures descending makes it a county full of stunning on the ‘town of books’, Hay on Wye landscapes, not least with the River in May and June, whilst music fans are Wye meandering its way through the catered for with Nozstock in July and county before making its way back into Lakefest in August. Wales. A visit to Herefordshire could see you visiting castles, canoeing on Herefordshire’s local crafts and artists the river, hiking up hills, walking the are to the forefront during h.Art week orchards, or simply taking in village life in September, whilst cider harvest is in with a chilled cider! full production during The Big Apple in October. Festivals & events, markets, local food and drink producers are in abundance, as this really is a ‘home-grown’ county. The welcome you will receive will make your trip as memorable as the sights you will see.