A Comparative Analysis of the Legal Means to Oppose the Use of Campaign Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Historic Recordings of the Song Desafinado: Bossa Nova Development and Change in the International Scene1

The historic recordings of the song Desafinado: Bossa Nova development and change in the international scene1 Liliana Harb Bollos Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brasil [email protected] Fernando A. de A. Corrêa Faculdade Santa Marcelina, Brasil [email protected] Carlos Henrique Costa Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brasil [email protected] 1. Introduction Considered the “turning point” (Medaglia, 1960, p. 79) in modern popular Brazi- lian music due to the representativeness and importance it reached in the Brazi- lian music scene in the subsequent years, João Gilberto’s LP, Chega de saudade (1959, Odeon, 3073), was released in 1959 and after only a short time received critical and public acclaim. The musicologist Brasil Rocha Brito published an im- portant study on Bossa Nova in 1960 affirming that “never before had a happe- ning in the scope of our popular music scene brought about such an incitement of controversy and polemic” (Brito, 1993, p. 17). Before the Chega de Saudade recording, however, in February of 1958, João Gilberto participated on the LP Can- ção do Amor Demais (Festa, FT 1801), featuring the singer Elizete Cardoso. The recording was considered a sort of presentation recording for Bossa Nova (Bollos, 2010), featuring pieces by Vinicius de Moraes and Antônio Carlos Jobim, including arrangements by Jobim. On the recording, João Gilberto interpreted two tracks on guitar: “Chega de Saudade” (Jobim/Moraes) and “Outra vez” (Jobim). The groove that would symbolize Bossa Nova was recorded for the first time on this LP with ¹ The first version of this article was published in the Anais do V Simpósio Internacional de Musicologia (Bollos, 2015), in which two versions of “Desafinado” were discussed. -

Stormzy in Concert

Stormzy in Concert UK & Ireland Tour – 2 – 23 April 2021 TOUR DATES 2021 Dates: 2 April - Dublin 3 April - Dublin 5 April - Glasgow 7 April - Newcastle 8 April - Leeds 9 April - Nottingham 12 April - London 13 April - London The multi award-winning rapper Stormzy got his start performing at youth clubs during the emergence of the 14 April - London UK grime scene. His Wicked Skegman series of 16 April - Bournemouth freestyle YouTube videos quickly began to attract 17 April - Birmingham attention, honing his own spin on the ever-growing 18 April - Manchester genre. 20 April - Cardiff Stormzy’s debut album Gang Signs & Prayer came out 21 April - Sheffield in 2017 and celebrated unprecedented mainstream attention thanks to singles like Blinded By Your 23 April - Liverpool Grace and Big For Your Boots. He went on to collect the BRIT Awards for Best British Album and Best Solo Male in 2018. Stormzy released his sophomore album Heavy Is The Head in December 2019. Showcasing both his lyricism and musicality, this collection contained Vossi Bop, Stormzy’s first No.1 song on the UK singles chart. The grime star heads on his H.I.T.H UK tour in April 2021. Buy Tickets & VIP Hospitality now. Now is an ideal time to book your tickets and/or VIP Hospitality Packages to see this year's tour live at your favourite venues. CONTACT US With over 40 years’ experience in the hospitality and live events industries, we regularly make arrangement on behalf of our clients in For further information, providing VIP Corporate Hospitality and tickets to check availability -

England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 25 22.06.2019

22.06.2019 England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 25 Pos Vorwochen Woc BP Titel und Interpret 2019 / 25 - 1 11151 5 I Don't Care . Ed Sheeran & Justin Bieber 222121 2 Old Town Road . Lil Nas X 333241 7 Someone You Loved . Lewis Capaldi 44471 2 Vossi Bop . Stormzy 555112 Bad Guy . Billie Eilish 67764 Hold Me While You Wait . Lewis Capaldi 78896 SOS . Avicii feat. Aloe Blacc 8 --- --- 1N8 No Guidance . Chris Brown feat. Drake 99939 Cross Me . Ed Sheeran feat. Chance The Rapper & PnB Rock 10 11 11 1110 All Day And Night . Jax Jones & Martin Solveig pres. Europa . 11 10 10 69 If I Can't Have You . Shawn Mendes 12 --- 14 309 Grace . Lewis Capaldi 13 15 --- 213 Shine Girl . MoStack feat. Stormzy 14 13 --- 213 Never Really Over . Katy Perry 15 24 39 315 Wish You Well . Sigala & Becky Hill 16 17 13 73 Me! . Taylor Swift feat. Brendon Urie Of Panic! At The Disco 17 6 6 132 Piece Of Your Heart . Meduza feat. Goodboys 18 --- --- 1N18 Mad Love . Mabel 19 --- --- 1N19 Stinking Rich . MoStack feat. Dave & J Hus 20 --- --- 1N20 Heaven . Avicii . 21 22 18 318 The London . Young Thug feat. J. Cole & Travi$ Scott 22 --- --- 1N22 Shockwave . Liam Gallagher 23 30 31 323 One Touch . Jesse Glynne & Jax Jones 24 27 23 618 Guten Tag . Hardy Caprio & DigDa T 25 14 --- 214 What Do You Mean . Skepta feat. J Hus 26 43 48 1526 Ladbroke Grove . AJ Tracey 27 34 29 327 Easier . 5 Seconds Of Summer 28 18 47 518 Greaze Mode . -

Risktaking Behavior in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

FULL-LENGTH ORIGINAL RESEARCH Risk-taking behavior in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy *†Britta Wandschneider, *†Maria Centeno, *†‡Christian Vollmar, *†Jason Stretton, §Jonathan O’Muircheartaigh, *†Pamela J. Thompson, ¶Veena Kumari, *†Mark Symms, §Gareth J. Barker, *†John S. Duncan, #Mark P. Richardson, and *†Matthias J. Koepp Epilepsia, 0(0):1–8, 2013 doi: 10.1111/epi.12413 SUMMARY Objective: Patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) often present with risk-tak- ing behavior, suggestive of frontal lobe dysfunction. Recent studies confirm functional and microstructural changes within the frontal lobes in JME. This study aimed at char- acterizing decision-making behavior in JME and its neuronal correlates using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Methods: We investigated impulsivity in 21 JME patients and 11 controls using the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), which measures decision making under ambiguity. Perfor- mance on the IGT was correlated with activation patterns during an fMRI working memory task. Results: Both patients and controls learned throughout the task. Post hoc analysis revealed a greater proportion of patients with seizures than seizure-free patients hav- ing difficulties in advantageous decision making, but no difference in performance between seizure-free patients and controls. Functional imaging of working memory networks showed that overall poor IGT performance was associated with an increased Dr. Wandschneider is activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in JME patients. Impaired registrar in neurology learning during the task and ongoing seizures were associated with bilateral medial and is pursuing a PhD prefrontal cortex (PFC) and presupplementary motor area, right superior frontal at the UCL Institute of gyrus, and left DLPFC activation. Neurology. -

Ebook Download This Is Grime Ebook, Epub

THIS IS GRIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hattie Collins | 320 pages | 04 Apr 2017 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781473639270 | English | London, United Kingdom This Is Grime PDF Book The grime scene has been rapidly expanding over the last couple of years having emerged in the early s in London, with current grime artists racking up millions of views for their quick-witted and contentious tracks online and filling out shows across the country. Sign up to our weekly e- newsletter Email address Sign up. The "Daily" is a reference to the fact that the outlet originally intended to release grime related content every single day. Norway adjusts Covid vaccine advice for doctors after admitting they 'cannot rule out' side effects from the Most Popular. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Definition of grime. This site uses cookies. It's all fun and games until someone beats your h Views Read Edit View history. During the hearing, David Purnell, defending, described Mondo as a talented musician and sportsman who had been capped 10 times representing his country in six-a-side football. Fernie, aka Golden Mirror Fortunes, is a gay Latinx Catholic brujx witch — a combo that is sure to resonate…. Scalise calls for House to hail Capitol Police officers. Drill music, with its slower trap beats, is having a moment. Accessed 16 Jan. This Is Grime. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More On: penn station. Police are scrambling to recover , pieces of information which were WIPED from records in blunder An unwillingness to be chained to mass-produced labels and an unwavering honesty mean that grime is starting a new movement of backlash to the oppressive systems of contemporary society through home-made beats and backing tracks and enraged lyrics. -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

The US Presidential Campaign Songster, 1840–1900

This is a repository copy of The US Presidential Campaign Songster, 1840–1900. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/132794/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Scott, DB orcid.org/0000-0002-5367-6579 (2017) The US Presidential Campaign Songster, 1840–1900. In: Watt, P, Scott, DB and Spedding, P, (eds.) Cheap Print and Popular Song in the Nineteenth Century: A Cultural History of the Songster. Cambridge University Press , Cambridge, UK , pp. 73-90. ISBN 9781107159914 https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316672037.005 © 2017, Paul Watt, Derek B. Scott and Patrick Spedding. This material has been published in Cheap Print and Popular Song in the Nineteenth Century: A Cultural History of the Songster edited by P. Watt, D. Scott, & P. Spedding. This version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2019 Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates Gary M. Bogers University of Central Florida Part of the Music Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bogers, Gary M., "Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates" (2019). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 511. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/511 MUSIC AND THE PRESIDENCY: HOW CAMPAIGN SONGS SOLD THE IMAGE OF PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES by GARY MICHAEL BOGERS JR. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Music Performance in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2019 Thesis Chair: Dr. Scott Warfield Co-chairs: Dr. Alexander Burtzos & Dr. Joe Gennaro ©2019 Gary Michael Bogers Jr. ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I will discuss the importance of campaign songs and how they were used throughout three distinctly different U.S. presidential elections: the 1960 campaign of Senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy against Vice President Richard Milhouse Nixon, the 1984 reelection campaign of President Ronald Wilson Reagan against Vice President Walter Frederick Mondale, and the 2008 campaign of Senator Barack Hussein Obama against Senator John Sidney McCain. -

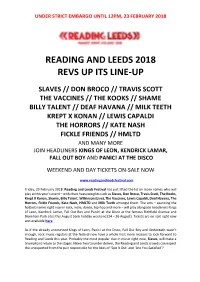

Reading and Leeds 2018 Revs up Its Line-Up

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 READING AND LEEDS 2018 REVS UP ITS LINE-UP SLAVES // DON BROCO // TRAVIS SCOTT THE VACCINES // THE KOOKS // SHAME BILLY TALENT // DEAF HAVANA // MILK TEETH KREPT X KONAN // LEWIS CAPALDI THE HORRORS // KATE NASH FICKLE FRIENDS // HMLTD AND MANY MORE JOIN HEADLINERS KINGS OF LEON, KENDRICK LAMAR, FALL OUT BOY AND PANIC! AT THE DISCO WEEKEND AND DAY TICKETS ON-SALE NOW www.readingandleedsfestival.com Friday, 23 February 2018: Reading and Leeds Festival has just lifted the lid on more names who will play at this year’s event – with chart heavyweights such as Slaves, Don Broco, Travis Scott, The Kooks, Krept X Konan, Shame, Billy Talent, Wilkinson (Live), The Vaccines, Lewis Capaldi, Deaf Havana, The Horrors, Fickle Friends, Kate Nash, HMLTD and Milk Teeth amongst them. The acts – spanning the hottest names right now in rock, indie, dance, hip-hop and more – will play alongside headliners Kings of Leon, Kendrick Lamar, Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco at the famous Richfield Avenue and Bramham Park sites this August bank holiday weekend (24 – 26 August). Tickets are on-sale right now and available here. As if the already announced Kings of Leon, Panic! at the Disco, Fall Out Boy and Underøath wasn’t enough, rock music regulars at the festival now have a whole host more reasons to look forward to Reading and Leeds this year. Probably the most popular duo in music right now, Slaves, will make a triumphant return to the stages. Never two to under deliver, the Reading and Leeds crowds can expect the unexpected from the pair responsible for the likes of ‘Spit It Out’ and ‘Are You Satisfied’? UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 With another top 10 album, ‘Technology’, under their belt, Don Broco will be joining the fray this year. -

Grime + Gentrification

GRIME + GENTRIFICATION In London the streets have a voice, multiple actually, afro beats, drill, Lily Allen, the sounds of the city are just as diverse but unapologetically London as the people who live here, but my sound runs at 140 bpm. When I close my eyes and imagine London I see tower blocks, the concrete isn’t harsh, it’s warm from the sun bouncing off it, almost comforting, council estates are a community, I hear grime, it’s not the prettiest of sounds but when you’ve been raised on it, it’s home. “Grime is not garage Grime is not jungle Grime is not hip-hop and Grime is not ragga. Grime is a mix between all of these with strong, hard hitting lyrics. It's the inner city music scene of London. And is also a lot to do with representing the place you live or have grown up in.” - Olly Thakes, Urban Dictionary Or at least that’s what Urban Dictionary user Olly Thake had to say on the matter back in 2006, and honestly, I couldn’t have put it better myself. Although I personally trust a geezer off of Urban Dictionary more than an out of touch journalist or Good Morning Britain to define what grime is, I understand that Urban Dictionary may not be the most reliable source due to its liberal attitude to users uploading their own definitions with very little screening and that Mr Thake’s definition may also leave you with more questions than answers about what grime actually is and how it came to be. -

The Music of Antonio Carlos Jobim

FACULTY ARTIST FACULTY ARTIST SERIES PRESENTS SERIES PRESENTS THE MUSIC OF ANTONIO THE MUSIC OF ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM (1927-1994) CARLOS JOBIM (1927-1994) Samba Jazz Syndicate Samba Jazz Syndicate Phil DeGreg, piano Phil DeGreg, piano Kim Pensyl, bass Kim Pensyl, bass Rusty Burge, vibraphone Rusty Burge, vibraphone Aaron Jacobs, bass* Aaron Jacobs, bass* John Taylor, drums^ John Taylor, drums^ Monday, February 13, 2012 Monday, February 13, 2012 Robert J. Werner Recital Hall Robert J. Werner Recital Hall 8:00 p.m. 8:00 p.m. *CCM Student *CCM Student ^Guest Artist ^Guest Artist CCM has become an All-Steinway School through the kindness of its donors. CCM has become an All-Steinway School through the kindness of its donors. A generous gift by Patricia A. Corbett in her estate plan has played a key role A generous gift by Patricia A. Corbett in her estate plan has played a key role in making this a reality. in making this a reality. PROGRAMSelections to be chosen from the following: PROGRAMSelections to be chosen from the following: A Felicidade Falando de Amor A Felicidade Falando de Amor Bonita The Girl from Ipanema Bonita The Girl from Ipanema Brigas Nunca Mais One Note Samba Brigas Nunca Mais One Note Samba Caminos Cruzados Photograph Caminos Cruzados Photograph Chega de Saudade So Tinha Se Con Voce Chega de Saudade So Tinha Se Con Voce Corcovado Triste Corcovado Triste Desafinado Wave Desafinado Wave Double Rainbow Zingaro Double Rainbow Zingaro Antonio Carlos Jobim was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to Antonio Carlos Jobim was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to cultured parents. -

Bullets High Five

DUC REDAKTION Hofweg 61a · D-22085 Hamburg T 040 - 369 059 0 WEEK 09 [email protected] · www.trendcharts.de 25.02.2021 Approved for publication on Tuesday, 02.03.2021 THIS LAST WEEKS IN PEAK WEEK WEEK CHARTS ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 01 04 Fat Joe, DJ Khaled & Amorphous Sunshine (The Light) RNG/Empire 01 02 03 02 G-Eazy Ft. Chris Brown & Mark Morrison Provide RCA/Sony 02 03 02 02 Cardi B Up Atlantic/WMI/Warner 02 04 04 06 Saweetie Ft. Doja Cat Best Friend ICY/Warner/WMI 02 05 06 09 Jason Derluo x Nuka Love Not War Ridge Maukava/Robots & Humans/Sony 02 06 09 09 24kGoldn Ft. DaBaby Coco Columbia/Sony 04 07 05 03 50 Cent Ft. NLE Choppa & Rileyy Lanez Part Of The Game G-Unit 05 08 11 07 Apache 207 Angst Two Sides/Four/Sony 03 09 12 09 Pia Mia With Sean Paul & Flo Milli HOT (Remix) Electric Feel/Republic/UMI/Universal 09 10 16 05 RIN Dirty South Division/Gold League/Sony 06 11 15 02 Yxng Bane Ft. Nafe Smallz & M Huncho Dancing On Ice Disturbing London/Parlophone UK/WMI/Warner 11 12 NEW Headie One Ft. Burna Boy Siberia Relentless/Sony 12 13 NEW Young Stoner Life, Young Thug & Meek Mill Ft. T-Shyne That Go! YSL/300/Atlantic/WMI/Warner 13 14 26 03 > Cro ALLES DOPE truworks/Urban/VEC/Universal 14 15 10 04 Tyga & DJ Drama Ft. DJ Chose Let Me Find Out White 03 16 NEW Smokepurpp 200 Thou Alamo/Geffen/UMI/Universal 16 17 19 04 PA Sports & Capital Bra Hell Life Is Pain/Major Movez/Chapter One/Universal 17 18 20 08 CJ Whoopty CJ/Warner/WMI 14 19 NEW Jamule & Capital Bra No Comprendo Life Is Pain/Major Movez/Chapter One/Universal 19 20 22 03 Maluma Agua De Jamaica Sony Latin/Sony 19 21 NEW Lil Mosey Enough Mogul Vision/Interscope/UMI/Universal 21 22 18 03 Ghetts Ft.