Carafano Appellant Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nana Visitor/Chase Masterson Interviews JARRAH

Episode 14: Nana Visitor/Chase Masterson Interviews JARRAH: Hi and welcome to Women At Warp. Join us as our crew of four women Star Trek fans boldly go on our biweekly mission to explore our favorite franchise. My name's Jarrah and thanks for tuning in. Today we have with us the rest of our crew. Sue SUE: Hi everybody JARRAH: Andi. ANDI: Hey everyone. JARRAH: And Grace. GRACE: Hey y'all. JARRAH: And before we get started into the main bulk of our show, which is interviews that I did at Star Trek Las Vegas with Chase Masterson and Nana Visitor from Deep Space Nine, we wanted to take a minute to pay tribute to a awesome Star Trek guest star that passed away recently: Yvonne Craig. So Andi, do you want to start with that? ANDI: Sure. I mean, I know a lot of people know her from Batgirl. I sadly never got to see her as Batgirl and wasn't really familiar with her from that. So my first experience with her as an actress was from Whom Gods Destroy, which is a third season Star Trek the original series episode. And I think it's a really cool episode. And the main reason I like it is because of her character Marta, who is awesome, and funny, and dangerous, and just really really cool. I mean she dances, and she stabs Kirk, and she quotes Shakespeare but pretends she wrote it. I mean how do you get such a cool character all in one place like that? It was really awesome and that's one of my favorite characters they ever did. -

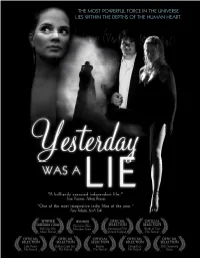

Pressive and Photographs So Beautifully, He Is Extremely Strong in This Role,” Comments Masterson

“YESTERDAY WAS A LIE” PRODUCTION INFORMATION A groundbreaking new noir film, YESTERDAY WAS A LIE is a “soulful and thought- provoking metaphysical journey” (Talking Pictures). Award-winning writer/director James Kerwin -- “one of these young guys on the edge of a digital revolution” (Soundwaves Cinema) -- crafts a thrilling, intricate detective drama that teases the boundaries of reality. Kipleigh Brown “exudes Bacall” (Slice of SciFi) as Hoyle, a girl with a sharp mind and a weak- ness for bourbon who finds herself on the trail of a reclusive genius (John Newton). But her work takes a series of unforeseen twists as events around her grow increasingly fragmented... discon- nected... surreal. With a sexy lounge singer (Chase Masterson) and a loyal partner (Mik Scriba) as her only allies, Hoyle is plunged into a dark world of intrigue and earth-shattering cosmological secrets. Haunted by an ever-present shadow (Peter Mayhew) whom she is destined to face, Hoyle discovers that the most powerful force in the universe -- the power to bend reality, the power to know the truth -- lies within the depths of the human heart. “Like Blade Runner before it, YESTERDAY WAS A LIE manages to meld film noir and science fiction into a fresh new world unlike anything we’ve seen be- fore” (iF Magazine). Also starring Nathan Mobley, Warren Davis, Megan Henning, Jennifer Slimko, and famed ra- dio personality Robert Siegel. 2 ABOUT THE PRODUCTION YESTERDAY WAS A LIE is the brainchild of writer/director James Kerwin, who made a splash in 2000 with his multi-festival-award-winning short film Midsummer. -

Trek XI Won't Be

15 15 15 Publication of the U.S.S. Chesapeake Star Trek and Science-Fiction Club January, 2009 Trek XI won’t be “too steamy;” Abrams assures fans of quality Despite hints in the trailer, don’t expect Television Critics Association press tour. “It Star Trek XI to be too steamy, according to honors what’s come before, but I didn’t really Chris Pine, who plays James T. Kirk. make the movie just for the people who are al- As reported by E!Online, in spite of Pine’s ready inside, because I like Star Trek but I was previous statement that the Star Trek franchise never a massive fan. So I think the movie’s go- Chris Pine says not to expect crazy sex in had been “sexed up for a new generation,” ing to not satisfy everyone, of course. It can’t. Trek XI. don’t expect anything that goes over the line. But it’ll satisfy most of both.” “It is a different Star Trek, but there’s no crazy Abrams made another effort to respond to sex scene,” said Pine, speaking at the HBO William Shatner’s recent YouTube interview, Golden Globes party. “There may be some in which the original Kirk actor disputed ever bare midriffs, but you know it’s been a long being asked by Abrams to appear in the film. time since the bikini was invented, so I don’t “I think what Mr. Shatner was responding think we’re going to ruffle any feathers.” to was a misunderstanding,” Abrams said. -

Star Trek the Movie

Vol 1 Issue 8 2008 Want to know about the StarStar TrekTrek new StarStar TrekTrek Movie? Then check out www.genews-ezine.com See the latest clips, pictures and links to keep you up to date. As we are an authorized Webmaster Site. GE News gets information straight from Paramount! Star Wars author Sean Williams interviewinterview (Part(Part 1)1) “Yesterday was a Lie” New Chase Masterson Movie, what is it? Plus a behind the scenes TheThe MovieMovie looklook onon thethe set!set! Star Trek work 2008 PARAMOUNT PICTURES ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Website www.genews-ezine.com ARMAGEDDONARMAGEDDON 20082008 For months we had been waiting in anticipation for Armageddon 2008, not just because of all the guests, but the fact that we were going to help with the autograph line for Michael Shanks (yum!!) and David Anders (mmm not too bad on the eyes either). It was disappointing to find that neither of them would be there due to other commitments. Not to worry as the other two guests who came, we were happy enough to meet, Gary Jones (the ‘Chevron One Encoding’ guy from Stargate SG-1) and Kavan Smith from 4400, Stargate SG-1 and Stargate Atlantis. In fact there were to be 5 guests who have been in Stargate!! An impressive line up. Our journey to Melbourne started at a civilized time this year. But we arrived early Friday afternoon at Adelaide Airport to find that our plane had been delayed for 90 minutes instead of arriving at a reasonable hour now we were not going to! Hopefully the rest of the weekend was not going to have as many delays. -

Schöne Neue Welt?

DIGITALISIERUNG UND SCIENCE FICTION Schöne neue Welt? Veranstaltungsreihe 2019 zur Zukunft in der Gegenwart Alle Infos: www.vhs.at/digitalisierung Foto: shutterstock Foto: SCHWERPUNKT DIGITALISIERUNG UND SCIENCE FICTION Podiumsgespräch: Lesekreis: Das Phänomen cyber_feminismus & beyond Star Trek Cyber- und Technofeminismus in Texten von Science Fiction, Donna Haraway und anderen Autor*innen Technologie und Politik Mo. 14. Okt. / Mo. 28. Okt. und mit Chase Masterson, Originaldarstellerin der Mo. 11. Nov. 2019 Bajoranerin „Leeta“ in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine; jeweils von 18.00 bis 20.30 Uhr Max Grodenchik, Originaldarsteller des Ferengis Galileigasse 8, 1090 Wien VHS Alsergrund, „Rom“ in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine 18.00 Uhr Leitung: Betina Aumair, Literatur- Do. 14. Nov. 2019, wissenschafterin und Genderforscherin VHS Ottakring, Ludo-Hartmann-Platz 7, 1160 Wien Moderation: Johannes Grenzfurthner, Lesekreis: Künstler, Autor und Filmemacher – „Smart Lies“ Künstler*innengruppe monochrom Ausgewählte Texte aus dem 2018 erschienenen Band, der sich den Schattenseiten der kleinen Videokreis: „smarten“ Geräte in unserer schönen neuen Gesellschaftspolitik Technik-Welt widmet. und soziale Utopien im Di. 15. Okt. 2019, 17.00 bis 20.00 Uhr Star Trek-Universum VHS Mariahilf, Damböckgasse 4, 1060 Wien Episoden aus Star Trek-Serien werden Leitung: Barbara Wimmer, Netzjournalistin, gemeinsam angesehen und analysiert. Autorin und Herausgeberin von „Smart Lies“ Di. 26. Nov. / Di. 3. Dez. und Do. 12. Dez. 2019 Vortrag und Diskussion: jeweils von 17.00 bis 20.00 Uhr Utopie oder bald Wirklichkeit? VHS Meidling, Längenfeldgasse 13-15, Gesellschaftspolitische Ansätze in Science Fiction 1120 Wien Mi. 20. Nov. 2019, 17.00 bis 20.00 Uhr Leitung: Johannes Grenzfurthner, VHS Wiener Urania, Uraniastraße 1, 1010 Wien Künstler, Autor und Filmemacher – Leitung: Johannes Grenzfurthner, Künstler*innengruppe monochrom Wien 1090 50, GmbH, Lustkandlgasse Volkshochschulen Wiener Die Künstler, Autor und Filmemacher – Druck: druck.at, 2544 Leobersdorf / Programmänderungen vorbehalten. -

STAR TREK LAS VEGAS 2018 - SCHEDULE of EVENTS

STAR TREK LAS VEGAS 2018 - SCHEDULE of EVENTS MONDAY, JULY 30TH START END EVENT LOCATION 2:00 PM 7:00 PM VENDORS SET-UP/VENDORS ONLY Amazon TUESDAY, JULY 31ST NOTE: Pre-registration is not a necessity, just a convenience! Get your credentials, wristband and schedule so you don't have to wait again during convention days. VENDORS ROOM WILL BE OPEN TOO so you can get first crack at autograph and photo op tickets as well as merchandise! PRE-REGISTRATION IS ONLY FOR FULL CONVENTION ATTENDEES WITH EITHER GOLD, CAPTAIN’S CHAIR, COPPER OR GA WEEKEND. If you miss this pre-registration time, you can come any time that Registration is open! START END EVENT LOCATION VENDORS ROOM – HOURS OF OPERATION: 9:00 AM 6:00 PM VENDORS SET-UP Amazon 6:00 PM 6:45 PM Vendors room open for GOLD ONLY Amazon 6:45 PM 7:30 PM Vendors room open for GOLD and CAPTAIN’S CHAIR ONLY Amazon 7:30 PM 8:15 PM Vendors room open for GOLD, CAPTAIN’S CHAIR and COPPER ONLY Amazon 8:15 PM 10:30 PM Vendors room open for GOLD, CAPTAIN’S CHAIR, COPPER AND GA WEEKEND ONLY Amazon PRE-REGISTRATION – HOURS OF OPERATION: 2:00 PM 3:30 PM GOLD PATRONS Rotunda 3:30 PM 4:30 PM CAPTAIN’S CHAIR PATRONS plus GOLD Rotunda 4:30 PM 6:00 PM COPPER PATRONS plus GOLD and CAPTAIN’S CHAIR Rotunda 6:00 PM 7:30 PM GENERAL ADMISSION FULL WEEKEND plus GOLD, CAPTAIN’S CHAIR & COPPER Rotunda 7:30 PM 10:00 PM REGISTRATION OPEN FOR ALL WEEKEND PASS HOLDERS Amazon WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 1ST WHERE’S WHAT? CBS All-Access Stage: Brasilia 7, Main Theatre: Pavilion, Photo op pick-up: Miranda 1-4, Photo ops: Miranda 5-8, Quark’s: Brasilia 1-3, Secondary Theatre: Brasilia 4-6, Ten Forward Lounge: Tropical G, The Original Bridge Set: Palma, TNG Display: Tropical E-F Vendors: Amazon PLEASE MAKE SURE TO SHOW UP AT THE START TIME TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS ANYTHING! WE CANNOT GUARANTEE A REPLACEMENT IF YOU MISS YOUR PHOTO OP OR AUTOGRAPH TIME. -

Dark Eyes New Companion Ruth Bradley Talks!

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES DARK EYES NEW COMPANION RUTH BRADLEY TALKS! PLUS! BOUNTY HUNTING WITH CHASE MASTERSON! ISSUE 45 • NOVEMBER 2012 JONATHAN MORRIS VOYAGES TO VENUS! SNEAK PREVIEWS EDITORIAL AND WHISPERS o, at last, Doctor Who: Dark Eyes is released VIENNA: THE MEMORY BOX this month! I hope you’ll all forgive me a S particularly self-indulgent editorial this month (what do you mean, ‘they always are’?!?). The release of Dark Eyes is the end of a very long journey for me. I have personally invested so much time and energy in it and the enormity of it is only just really occurring to me. I had this mad idea to write and direct a box set of Doctor Who all by myself! And it’s happened… The truth is, of course, that I didn’t do it all by myself. Right from the story and script stage, I had our brilliant script editor Alan Barnes ometimes things just work. And they work advising and guiding me. And then, to get it so instantly and so perfectly that you want actually recorded, David Richardson brought his S more. To be honest, it was sheer considerable organisational and casting skills to serendipity that Chase Masterson was cast as the bear. Along the way, comedy genius Paul Spragg mercenary assassin Vienna Salvatori in the gave me great encouragement, telling me how upcoming Doctor Who story The Shadow Heart. much he enjoyed reading the script (let’s hope But from the day of recording it became clear that he wasn’t joking, the wag!). -

The History of STAR TREK Fan Films

Executive Summary A History of STAR TREK Fan Films Prepared by Jonathan Lane January 2016 This executive summary provides an overview of the independent amateur films made by fans using derivative intellectual property of the Star Trek franchise copyright and trademark holders over the past 50 years. None of the “fan films” listed in this document had a license or approval from CBS, Paramount, Viacom, or Gulf & Western (all of whom held the Star Trek rights over the past five decades). The fan films and series are presented here in a general chronological order by initial release date, although there is unavoidable overlap for series that released new offerings over a period of years. I have endeavored to briefly summarize for each production the content, people involved, and level of professionalism/quality, and (when possible) specifics as to the specific IP used from the long history of the Star Trek franchise. You’ll note that the quality of fan films ranges from the nearly unwatchable to professional-level productions that could easily be mistaken for broadcast television programming or even movie-theater fare. I have also indicated with a star (*) ranking how well known each film/series is generally among Star Trek fans. The rankings are as follows: (*) – Not well known (less than 10K views on YouTube/Vimeo) (**) – Somewhat known (10K-100K views on YouTube/Vimeo) (***) – Mostly known (100K-1M views on YouTube/Vimeo) (****) – Very popular (1M+ views on YouTube/Vimeo) When possible, I have also indicated the amount of money spent on each production and whether or not the project was crowdfunded on Kickstarter, Indiegogo, or some other online service. -

Women at Warp Episode 115: Behind the Lens with Hanelle Culpepper

Women at Warp Episode 115: Behind the Lens with Hanelle Culpepper SUE: Hi and welcome to Women At Warp: A Roddenberry Star Trek podcast. Join us as our crew of four women Star Trek fans boldly go on our biweekly mission to explore our favorite franchise. My name is Sue and thanks for tuning in. With me today is my lovely co-host Jarrah. JARRAH: Hello. SUE: Before we get into today's main topic, as usual, we have a little bit of housekeeping to do first. Our show is entirely supported by our patrons on Patreon. If you'd like to become a patron you can do so for as little as one dollar per month and get awesome rewards from thanks on social media, to silly watchalong commentaries. And now even some extra non-Trek content in the feed at certain levels. So if you'd like to join us at any level every little bit helps. You can do so at Patreon.com/WomenAtWarp. You can also support us by leaving a rating or review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. JARRAH: Before we get into our main topic, which is an awesome interview that Sue did with Hanelle Culpepper who is one of the Star Trek's few women directors, and she will be the first black woman to- well she's the first woman to direct a pilot of a Star Trek series. And she was the first black woman to direct Star Trek, I believe. So I'm excited for that, but of course a couple of little pieces of news and announcements from our show and from the Roddenberry Podcast Network. -

September 2000

SHIP‘S SECTIONS Hailing Frequencies open 4 New Crewmembers 4 Communication Center 4 Was wäre wenn... 8 Galactic Friendship Classics 16 News 18 3. Bowlingfinale 2000 21 X-Men Review 22 Starfleet History Tapes: „The Cloud“ 24 Luigis Vermischtes 32 Humor 36 TNG-Tapes: „Hide &Q“ 38 GF-Clubshop 42 ACHTUNG WICHTIG! 44 1. Galactic Friendship LAN-Party Wochenende 45 Neuerscheinungen 45 Cyrano Jones‘ Warenlager 46 Termine 45 Impressum: Stardate ist die Clubzeitschrift des Vereins „Galactic Friendship“. Verlagsort: 1210 Wien, Kummergasse 7/5/1A Redaktion: Reinhard Ullmer, Karin Embacher, Günter Leitner, Manfred Stefanek,Peter Zinner, Maria Nausch. Editor: Reinhard Ullmer Front+Rückencover: Quelle: Internet; Bearbeitung: Reinhard Ullmer Innencover: ; Bearbeitung: Reinhard Ullmer Beiträge für den Newsletter (in PC-Formaten) als E-Mail an [email protected]; Auf Diskette oder Papier an 1180 Wien, Staudgasse 3/5. Für die Retournierung der Disketten legt bitte das Rückporto bei, bzw. wenn möglich werden wir sie bei Meetings etc. persönlich zurückgeben. Vorstandsangelegenheiten oder Fragen zum Clubshop an Karin Embacher, Tel 29 00 686 oder E-Mail: [email protected] Nachdruck, auch auszugsweise, nur mit Genehmigung der Redaktion. Anm d. Red: Die in „Stardate“ veröffentlichten Artikel geben nicht unbedingt die Meinung der Redaktion wieder. Ehrenmitglieder: Marc Alaimo, Richard Arnold, Robin Curtis, Lolita Fatjo, Max Grodenchik, Walter Koenig, Judy Lewitt, Barbara March, Chase Masterson, Leo Moser, Majel Barrett Roddenberry, George Takei, Gwynyth Walsh Offizielle -

Aaron Douglas Aaron Douglas Is Best Known for His Portrayal of Chief Galen Tyrol on Syfy’S Battlestar Galactica

E komo mai! Welcome to the third annual HawaiiCon SEPTEMBER 15-18, 2016 We can’t wait to share everything we have been work- ing on all year with you, but first a few things to note: · Look over the schedule and plan ahead. Panels are all included in your Pass, but many special paid events (tours especially) fill up quickly and sell out! · Stay hydrated! There is so much awesome stuff happening you might forget, but drink up. Bring a water bottle, but if no can, most panel rooms have free water. · Having a blast? Buy tickets for next year now. This saves 40% and helps us put together an even bet- ter convention for our 2017 Star Wars and Whedon/ Espenson Celebration. · Post your pictures to Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat and Facebook with #HawaiiCon. Our greatest joy after putting this on is to see your photos too! · Finally, Cosplay is not consent! Just because you want to touch, doesn’t mean you can. If you want to take a picture, ask first. We’re all family, so treat each other like your favorite brother or sister. Questions? The HawaiiCon Concierge Desk is op- posite the Registration area in the Mauna Lani main lobby. You can also book all extra goodies like tours and photo-ops there. Make sure to stay in touch via www.hawaiicon.com, on Facebook.com/HawaiiCon, Twitter@HawaiiCon, Snap- chat hawaiicon, and Instagram.com/HawaiiCon. Enjoy the Con and the beach! with much Aloha, The HawaiiCon ‘Ohana PROGRAM GUIDE Guest Stars’ Bios ............................................................ 2 Guest Scientists & Moderators ......................................9 -

'Not a Film' Makes Powerful Statement

SPOTLIGHT Saturday-Sunday, March 3-4, 2012 | Editor: Eli Pace | 270-887-3235 | [email protected] AT THE MOVIES n ASSOCIATED PRESS In this image released by Palisades Tartan, Jafar Panahi is shown in a scene from “This is Not a Film.” ASSOCIATED PRESS In this film image released by Magnolia Pictures, Eric Ware- heim (left) and Ray Wise are shown in a scene from “Tim & Er- ‘Not a Film’ makes ic's Billion Dollar Movie.” ‘Tim & Eric’ make powerful statement leap to big screen The cult comedy of Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim gets its first big-screen showing, a faithful if not exceptional example of their BY CHRISTY LEMIRE tion party in Iran’s 2009 election. ing to shoot — blocks off part of his unique brand of mania. AP MOVIE CRITIC He’s no longer under house arrest living room with tape, acts it out, ex- Tim and Eric, given $1 billion by studio exec- but remains in limbo while awaiting plains the motivations of the young utives to make a movie, have turned in a three- Everything about “This Is Not a his fate. “This Is Not a Film” was woman who’s his lead character. He minute disaster no thanks to their spiritual Film” is cleverly deceptive, from the smuggled out in a cake just in time shows clips from previous films and guru, Jim Joe Kelly (Zach Galifianakis). They title that’s so self-deprecating, it for screening at last year’s Cannes tells stories from behind the scenes. skip town, where they’re lured by promises of sounds like a shrug to its long, first Film Festival.