Procurement and Distribution of Pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican Obsidian 900 BC–AD 1520: a Social Network Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

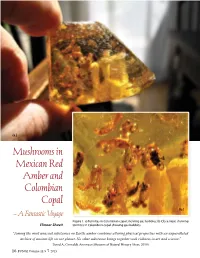

“Among the Most Unusual Substances on Earth, Amber Combines Alluring Physical Properties with an Unparalleled Archive of Ancient Life on Our Planet

(a.) (b.) Figure 1. a) Termites in Colombian copal showing gas bubbles; b) Close view, showing termites in Colombian copal showing gas bubbles. “Among the most unusual substances on Earth, amber combines alluring physical properties with an unparalleled archive of ancient life on our planet. No other substance brings together such richness in art and science.” David A. Grimaldi, American Museum of Natural History (Ross, 2010) 16 FUNGI Volume 11:5 2019 Figure 2. A rough piece of blue Dominican amber. y quest for mushrooms in Mushroom lovers were treated to a and so versatile. As a gemologist, amber amber and copal lasted about small, extremely rare piece of light- was an organic, semi-precious gemstone a decade, from the mid-1990s colored amber, inside which a tiny gilled for me, soft for a gemstone (only 2-2.5 Mto the early part of the 2000s. During mushroom was barely visible. Through on the Mohs scale), and with multiple this period of time, I found mushrooms a strategically placed magnifying glass, places of origin around the world. It in Mexican red amber from Chiapas, excited visitors could get a glimpse of came in multiple colors, and lended itself and in Colombian copal from the what the ancestor of today’s Mycena to carving and the creation of beautiful Santander region; these pieces make up looked like, down to its cap, delicate works of art. As a mycologist seeking the bulk of my collection. The unique gills, and stipe. Though an extinct mushrooms inside the amber, amber fossils of mushrooms, amber, and copal species and millions of years old, the was the fully polymerized tree resin that in this collection are still waiting to be fossilized mushroom looked fresh and formed millions of years ago in what studied. -

Imitation Amber Beads of Phenolic Resin from the African Trade

IMITATION AMBER BEADS OF PHENOLIC RESIN FROM THE AFRICAN TRADE Rosanna Falabella Examination of contemporary beads with African provenance reveals large quantities of imitation amber beads made of phenol- formaldehyde thermosetting resins (PFs). This article delves into the early industrial history of PFs and their use in the production of imitation amber and bead materials. Attempts to discover actual sources that manufactured imitation amber beads for export to Africa and the time frame have not been very fruitful. While evidence exists that PFs were widely used as amber substitutes within Europe, only a few post-WWII references explicitly report the export of imitation amber PF beads to Africa. However they arrived in Africa, the durability of PF beads gave African beadworkers aesthetic freedom not only to rework the original beads into a variety of shapes and sizes, and impart decorative elements, but also to apply heat treatment to modify colors. Some relatively simple tests to distinguish PFs from other bead materials are presented. Figure 1. Beads of phenol-formaldehyde thermosetting resins INTRODUCTION (PFs) from the African trade. The large bead at bottom center is 52.9 mm in diameter (metric scale) (all images by the author unless otherwise noted). Strands of machined and polished amber-yellow beads, from small to very large (Figure 1), are found today in the He reports that other shapes, such as barrel and spherical stalls of many African bead sellers as well as in on-line (Figure 2), were imported as well, but the short oblates stores and auction sites. They are usually called “African are the most common. -

Save/View This Catalog in PDF Format

H O W A R D N O W E S A N C I E N T A R T www.howardnowes.com - 6 - www.howardnowes.com www.howardnowes.com HOWARD NOWES ANCIENT ART ANCIENT ART & ARTIFACTS Volume III, No. 2 Winter 2001 $5.00 Welcome to this Holiday edition of GALLERY SERVICES Ancient Art & Artifacts. This catalog contains Let us sell your antiquities! We can an excellent range of sculpture and ceramics, sell your collections in our gallery, through each piece chosen for their uniqueness and direct mail or at public auction, where the competitive bidding enviornment can be eye appeal. Objects are easily viewable in full suprisingly benificial. color online at www.howardnowes.com where condition reports are also available. If We offer restoration & conservation, which is preformed by trained professionals in New York City, please call to schedule an with more the 20 years experience. appointment for a viewing in person. We Go on-line to art-restoration.net for full recommend that you check the availability of details. items to avoid disappointment. Custom mounting is done by an 5 2 experience talented artist with more then 25 TERMS OF SALE years of experience. We offer appraisals for insurance pur- All items offered are unique and pouses and can help you with the valuation of subject to prior sale. Prices are in US dollars. objects. Just send us clear photos with sizes and 4 All sales are accompanied by a typed invoice, condition and follow up with a phone call. signed by our director, with all the relevant collection and provenance information. -

Curandera's Altar

5/16/2019 RUE, RESIN AND ROSE: SACRED AND MEDICINAL TRILOGY OF LATIN AMERICAN M A T E R I A MEDICA Mimi Hernandez, MS, RH(AHG) CURANDERA’S ALTAR 1 5/16/2019 RUE RUE 2 5/16/2019 SACRED RESINS 3 5/16/2019 RUE An herb of grace allowing us to screen out negative influences and clearly visualize and manifest our visionary potential. RUE At one time the holy water was sprinkled from brushes made of Rue at the ceremony usually preceding the Sunday celebration of High Mass, for which reason it is supposed it was named the Herb of Repentance and the Herb of Grace. 4 5/16/2019 RUE The fibrous roots of this herb reminded some people of the blood vessels in the eye, which may account for its use as an eyestrain treatment. Rue was once believed to improve the eyesight and creativity, and no less personages than Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci regularly ate the small, trefoil leaves to increase their own. RUE Rue is also used to give a person “second sight” and was believed to help see into the future. A potent remedy to ward off the “evil eye” or “mal ojo” 5 5/16/2019 RUE Also commonly known as the Herb of Fair Maidens in France, Rue has long been a symbol of virtue and purity. As part of traditional Lithuanian wedding rites, the bride wears a crown of Rue which is burned during the ceremony to symbolize her transition from the whimsy and virtue of childhood to the responsibilities of motherhood and adulthood. -

Copal Vs. Amber

Gems&Jewellery / Summer 2011 / Volume 20 / No. 2 Gem-A OrganicsCalendar Copal vs. amber Maggie Campbell Pedersen and Bear Williams investigate the infrared and optical characteristics of treated and natural ambers and copals. Part I: Observation and simple gemmological tests The correct identification of ambers and heat-treated Baltic amber — other ambers greened, 40 million year-old Baltic amber is copals can be extremely difficult. Not only are seldom, if ever, treated this way. This is more valuable than greened, 300 year-old are we expected to be able to differentiate because they are too rare and expensive, Colombian copal, and clarified and heat- between them, but we are also expected to and, secondly, the younger ambers such treated Baltic amber would be more valuable be able to recognize and identify all of the as those from Mexico or the Dominican than heat-treated copal used in imitation of treatments given to them. Unfortunately Republic have a lower melting point than Baltic amber. these are constantly increasing in number Baltic amber and would melt if heated to the The normal gemmological tests are and complexity. One treatment that is high temperatures necessary to produce the not very useful for resins. We know that appearing more and more is autoclave- fractures. However, nowadays we are seeing all ambers float in saturated salt water, treated copal (including the greened variety), copals treated in an autoclave to produce but so do natural or treated copals, as yet still many misunderstandings remain sun spangles. well as pressed amber. In general, specific gravity tests can therefore only differentiate about this material. -

Updated 2012

American Federation of Mineralogical Societies AFMS Approved Reference List of Lapidary Material Names “Gem List” August 1996 Updated January 2003 AFMS Pubications Committee B. Jay Bowman, Chair Internet version of Approved Lapidary Material Names. This document can only be downloaded at http://www.amfed.org/rules APPROVED NAMES FOR LAPIDARY LABELS Prepared by the American Federation Nomenclature Committee and approved by the American Federa- tion Uniform Rules Committee, this list is the authorized guide and authority for Lapidary Label Names for exhibitors and judges in all competition under AFMS Uniform Rules. All materials are listed alpha- betically with two columns on a page. The following criteria are to assist in the selection and judging of material names on exhibit labels. 1. The name of any listed material (except tigereye), which has been cut to show a single chatoyant ray, may be preceded by “CAT’S-EYE”; the name of any material which has been cut to show asterism (two or more crossed rays) may be preceded by “STAR”, i.e.: CATS-EYE DIOPSIDE, CAT’S-EYE QUARTZ, STAR BERYL, STAR GARNET, etc. 2. This list is not all-inclusive as to the names of Lapidary materials which may at some time be exhibited. If a mineral or rock not included in this list is exhibited, the recognized mineralogical or petrological name must be used. The names of valid minerals and valid mineral varieties listed in the latest edition of the Glossary of Mineral Species by Michael Fleisher, or any other authorized reference, will be acceptable as Lapidary names. Varieties need only have variety name listed and not the root species. -

Mushroom in Copal Gilalite Altered to Cuprite in Quartz

Editor Nathan Renfro Contributing Editors Elise A. Skalwold and John I. Koivula Mushroom in Copal Copal is widely popular among gem collectors due to its eclectic inclusion scenes. As a fossilized tree resin, copal can contain a wide range of flora, fauna, and inorganic ma- terials. It is not uncommon to find spiders, termites, leaves, and petals inside this resinous gem. In a 19.83 ct brownish orangy yellow copal, the author recently observed a re- markably well-preserved mushroom that was easily seen with the naked eye and had a cap that was just over 5.5 mm in diameter. Stalks of broken mushrooms, miscella- neous plant materials, and gas bubbles were also found in this specimen. Interestingly, copal was also used for many years by some indigenous peoples in Mexico and Central America as incense for ceremonial purposes such as the sa- cred mushroom ceremony. The mushroom inclusion in Figure 1. This copal from Mexico contained a this copal, reportedly from Mexico, may have a more sig- remarkably well-preserved eye-visible mushroom in- nificant meaning for the people of Mesoamerica that goes clusion. Photomicrograph by Nathan Renfro; field of beyond a gemological standpoint (figure 1). view 9.59 mm. Rebecca Tsang GIA, Carlsbad “Medusa quartz,” so named for the medusa phase of a jel- Gilalite Altered to Cuprite in Quartz lyfish, which has an umbrella-like shape similar to these In 2004, gem-quality quartz that contained blue to green brightly colored inclusions. One specimen of this material inclusions of the hydrated copper silicate mineral gilalite contained an unusual red inclusion with the same um- was found in Paraíba, Brazil. -

Identification and Care of Amber

Conserve O Gram September 2011 Number 11/17 Identification and Care of Amber Introduction Amber Products Amber can be cut, ground, heated, pressed and Amber is fossilized plant resin. During burial shaped into a variety of objects. Treated and (fossilization), the volatile components of resin untreated amber products have similar physical evaporate and the remaining hydrocarbons properties, except for color. polymerize and harden. Many museum col- lections contain amber, including archeologi- Clarified and colored amber. Cloudy amber is cal and fine art objects, and natural history slowly heated in a vegetable oil of similar refrac- specimens, either alone or in combination with tive index to clarify it. The oil fills the tiny other materials. This Conserve O Gram (COG) air bubbles that make it cloudy. Dyes may be provides guidance on the identification and care introduced to improve or darken the color. of amber. It does not address the preparation Heating can also produce “sun spangles” or or special care of fossiliferous amber. “flying saucers,” flat circular stress zones that are sometimes marketed as natural inclusions. Physical Properties of Amber Pressed amber or ambroid. Low-quality amber Color and opacity. Amber varies in color from and amber fragments are cleaned of impurities, honey yellow to off-white, through shades of ground, heated and pressed to form large blocks brown, yellow and red, to almost black. Rarely, used to make objects such as smoking parapher- it displays a greenish or bluish hue. Amber nalia, jewelry or ornaments. Ambroid often ranges from transparent to opaque, depending appears cloudy but pressed amber can also be on the amount of air bubbles and other inclu- clarified as described above. -

Signature Redacted Thesis Supervisor

An Assessment of Stingless Beeswax as a Pattern Material in Ancient Mesoamerican Lost-Wax Casting by Eleni Chrisoula Pitses Submitted to the Department of Mechanical Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2018 2018 Eleni Chrisoula Pitses. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of Author: Department of Mechanical Engineering May 11, 2018 Signature redacted Certified by: Michael J. Tarkanian Senior Lecturer in Materials Science and Engineering Signature redacted Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: MASSACH SETS INSTrrUTE Rohit Kamik QF TECHNOWGY Professor of Mechanical Engineering Undergraduate Officer SEP 13 2018 1 LIBRARIES ARCHIVES 2 An Assessment of Stingless Beeswax as a Pattern Material in Ancient Mesoamerican Lost-Wax Casting by Eleni Chrisoula Pitses Submitted to the Department of Mechanical Engineering on May 11, 2018 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering ABSTRACT Metal objects were of great cultural significance in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. Historical and archaeological evidence prove that these items were made by the process of investment casting, or "lost wax" casting, by which a wax model of the object is created, and a ceramic mold is built around it. The wax is melted out to allow for the pouring of the molten metal. Considerable research has focused on the alloy composition of these objects, and some research has been done on the ceramic molds, but little is known about the composition, source, and manufacture of the wax itself. -

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum

ANCIENT CARVED AMBERS IN THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM Faya Causey Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Faya Causey With technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael Schilling THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES This catalogue was first published in 2012 at http:// Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data museumcatalogues.getty.edu/amber. The present online version Names: Causey, Faya, author. | Maish, Jeffrey, contributor. | was migrated in 2019 to http://www.getty.edu/publications Khanjian, Herant, contributor. | Schilling, Michael (Michael Roy), /ambers; it features zoomable high-resolution photography; free contributor. | J. Paul Getty Museum, issuing body. PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads; and JPG downloads of the Title: Ancient carved ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum / Faya catalogue images. Causey ; with technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael Schilling. © 2019, J. Paul Getty Trust Description: Los Angeles : The J. Paul Getty Museum, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: “This catalogue provides a general introduction to amber in the ancient world followed by detailed catalogue entries for fifty-six Etruscan, Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Greek, and Italic carved ambers from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a The volume concludes with technical notes about scientific copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4 investigations of these objects and Baltic amber”—Provided by .0/. Figs. 3, 9–17, 22–24, 28, 32, 33, 36, 38, 40, 51, and 54 are publisher. -

Imitation Amber Beads of Phenolic Resin from the African Trade

BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers Volume 28 Article 4 2016 Imitation Amber Beads of Phenolic Resin from the African Trade Rosanna Falabella Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/beads Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Science and Technology Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Repository Citation Falabella, Rosanna (2016). "Imitation Amber Beads of Phenolic Resin from the African Trade." BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers 28: 3-15. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/beads/vol28/ iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in BEADS: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEADS Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers 2016 Vol. 28 IMITATION AMBER BEADS OF PHENOLIC RESIN FROM THE AFRICAN TRADE Rosanna Falabella Examination of contemporary beads with African provenance reveals large quantities of imitation amber beads made of phenol- formaldehyde thermosetting resins (PFs). This article delves into the early industrial history of PFs and their use in the production of imitation amber and bead materials. Attempts to discover actual sources that manufactured imitation amber beads for export to Africa and the time frame have not been very fruitful. While evidence exists that PFs were widely used as amber substitutes within Europe, only a few post-WWII references explicitly report the export of imitation amber PF beads to Africa. However they arrived in Africa, the durability of PF beads gave African beadworkers aesthetic freedom not only to rework the original beads into a variety of shapes and sizes, and impart decorative elements, but also to apply heat treatment to modify colors.