A Journal of African Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War and Peace in Ireland and Southern Africa. London and New York: I.B

Document generated on 09/30/2021 10:46 a.m. Journal of Conflict Studies Weiss, Ruth. Peace in Their Time: War and Peace in Ireland and Southern Africa. London and New York: I.B. Tarus, 2000. Richard Dale Volume 22, Number 2, Fall 2002 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/jcs22_2br06 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 1198-8614 (print) 1715-5673 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Dale, R. (2002). Review of [Weiss, Ruth. Peace in Their Time: War and Peace in Ireland and Southern Africa. London and New York: I.B. Tarus, 2000.] Journal of Conflict Studies, 22(2), 161–163. All rights reserved © Centre for Conflict Studies, UNB, 2002 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ The Journal of Conflict Studies Weiss, Ruth. Peace in Their Time: War and Peace in Ireland and Southern Africa. London and New York: I.B. Tarus, 2000. One of the classic analyses in the field of comparative politics is Roy C. Macridis’ The Study of Comparative Government, published as a small mono- graph by Doubleday & Company in 1955. Now probably found only in larger university libraries and superseded by longer, more sophisticated critiques, his work evaluated the state of the subdiscipline at the time and heralded what could be called the golden age of comparative politics. -

Smith Alumnae Quarterly

ALUMNAEALUMNAE Special Issueue QUARTERLYQUARTERLY TriumphantTrT iumphah ntn WomenWomen for the World campaigncac mppaiigngn fortififorortifi eses Smith’sSSmmitith’h s mimmission:sssion: too educateeducac te wwomenommene whowhwho wiwillll cchangehahanngge theththe worldworlrld This issue celebrates a stronstrongerger Smith, where ambitious women like Aubrey MMenarndtenarndt ’’0808 find their pathpathss Primed for Leadership SPRING 2017 VOLUME 103 NUMBER 3 c1_Smith_SP17_r1.indd c1 2/28/17 1:23 PM Women for the WoA New Generationrld of Leaders c2-50_Smith_SP17.indd c2 2/24/17 1:08 PM “WOMEN, WHEN THEY WORK TOGETHER, have incredible power.” Journalist Trudy Rubin ’65 made that statement at the 2012 launch of Smith’s Women for the World campaign. Her words were prophecy. From 2009 through 2016, thousands of Smith women joined hands to raise a stunning $486 million. This issue celebrates their work. Thanks to them, promising women from around the globe will continue to come to Smith to fi nd their voices and their opportunities. They will carry their education out into a world that needs their leadership. SMITH ALUMNAE QUARTERLY Special Issue / Spring 2017 Amber Scott ’07 NICK BURCHELL c2-50_Smith_SP17.indd 1 2/24/17 1:08 PM In This Issue • WOMEN HELPING WOMEN • A STRONGER CAMPUS 4 20 We Set Records, Thanks to You ‘Whole New Areas of Strength’ In President’s Perspective, Smith College President The Museum of Art boasts a new gallery, two new Kathleen McCartney writes that the Women for the curatorships and some transformational acquisitions. World campaign has strengthened Smith’s bottom line: empowering exceptional women. 26 8 Diving Into the Issues How We Did It Smith’s four leadership centers promote student engagement in real-world challenges. -

Registratur PA.43 Ruth Weiss Apartheid Und Exil, Politik Und

Registratur PA.43 Ruth Weiss Apartheid und Exil, Politik und Wirtschaft im südlichen Afrika: Teilsammlung der Journalistin und Autorin Ruth Weiss (*1924) Apartheid and Exile, Politics and Economy in Southern Africa: The Papers and Manuscripts of the Journalist and Writer Ruth Weiss (*1924) Zusammengestellt von / Compiled by Melanie Eva Boehi Basler Afrika Bibliographien Namibia Resource Centre – Southern Africa Library 2012 REGISTRATUR PA.43 Ruth Weiss in den späten 1970er Jahren in Köln. Ruth Weiss in the late 1970s in Cologne. (Fotograf unbekannt / Photographer unknown) Registratur PA.43 Ruth Weiss Apartheid und Exil, Politik und Wirtschaft im südlichen Afrika: Teilsammlung der Journalistin und Autorin Ruth Weiss (*1924) Apartheid and Exile, Politics and Economy in Southern Africa: The Papers and Manuscripts of the Journalist and Writer Ruth Weiss (*1924) Zusammengestellt von / Compiled by Melanie Eva Boehi Basler Afrika Bibliographien Namibia Resource Centre – Southern Africa Library 2012 © 2012 Basler Afrika Bibliographien Herausgeber / Publisher Basler Afrika Bibliographien P.O. Box 2037 CH 4001 Basel Switzerland www.baslerafrika.ch Alle Rechte vorbehalten / All rights reserved Übersetzungen / Translations: Dag Henrichsen (Basel) Gedruckt von / Printed by: Job Factory Basel AG ISBN 978-3-905758-37-5 Inhalt / Contents I Einleitung ix Ruth Weiss x Zur Überlieferung des Aktenbestandes xiii Der Aktenbestand xiv Anmerkungen zum Findbuch xvi Introduction xvii Ruth Weiss xviii On the History of the Collection xxi The Collection xxi Remarks -

Rundbrief 64

Vereinigung Schweiz-Zimbabwe Swiss-Zimbabwean Friendship Association Rundbrief / Newsletter Nr. 64, Nov. 2014 Editorial dass die reich vorhandenen Rohstoffe nicht zur Ent- wicklung Afrikas genutzt werden, sondern nach wie vor Präsident Mugabe hat alle überrascht. Nachdem er bis nur den Ausländern Vorteile bringen. Erstaunlicherwei- jetzt trotz seiner 90 Jahre innerhalb der Regierungspar- se war kaum eine kritische Stimme zu hören, die die tei Zanu-PF keine Nachfolge aufgebaut hatte, zauberte private Aneignung der Reichtümer (beispielsweise der er plötzlich seine mutmassliche Nachfolgerin aus dem Marange-Diamanten) durch die eigene Elite anklagte – Nichts: Seine Frau Grace. Grace, bis jetzt politisch nicht vielleicht, weil nur VertreterInnen der Elite anwesend in Erscheinung getreten, wurde plötzlich gegen alle Re- waren? geln Präsidentin der Frauenliga. Und nicht genug damit: Im Oktober erklärte Grace, sie fühle sich reif für die Prä- Der vorliegende Rundbrief vertieft unter anderem diese sidentschaft. Was wie eine Operette tönt, ist aber Reali- Themen. tät. Wie gehen gestandene Parteiaktivisten und das Mi- Gertrud Baud, Mitglied des Vorstandes litär mit dieser neuen Lage um? In Zimbabwes Verfassung ist ein Grundrechtskatalog enthalten. Leider hält sich aber Regierung und Verwal- Der wundersame Aufstieg von tung (noch) nicht daran. Es gibt nach wie vor willkürli- Grace Mugabe che Schikanen und Verhaftungen von AktivistInnen der Zivilgesellschaft (beispielsweise von Woza) oder unan- Ruth Weiss gekündigte Zerstörungen von Kiosken (beispielsweise durch den Harare City Council). Die AktivistInnen las- Viele Probleme, wenige Lösungen sen sich nicht entmutigen und ziehen die Verantwortli- chen gestützt auf die verfassungsmässigen Rechte vor Nichts ist so in der Republik von Zimbabwe, wie es sein Gericht. Eine Sisyphusarbeit? sollte: Unternehmen schliessen, allein im August 623. -

Im Dialog Unser Neuer Zeitung Der Stadt Aschaffenburg Für Ihre Bürgerinnen Und Bürger Hauptbahn- Nummer 28 · Juli 2010 Hof Wächst in Beeindruckender Geschwindig- Keit

Liebe Bürgerinnen und Bürger, im Dialog unser neuer Zeitung der Stadt Aschaffenburg für ihre Bürgerinnen und Bürger Hauptbahn- Nummer 28 · Juli 2010 hof wächst in beeindruckender Geschwindig- keit. Bald besitzt Aschaffenburg ein Bahnhofs- gebäude, das sich als moder- nes Eingangstor in die Stadt überregional sehen lassen kann. Der Zusammen mit dem Regionalen Spielplatz Omnibusbahnhof wird sich der am Liebig Hauptbahnhof als pulsierende platz ist Drehscheibe für die ganze Regi- das erste on erweisen. Doch nicht nur für Projekt der die Reisenden und die Pendler Sozialen im öffentlichen Nahverkehr ist Stadt: der Bahnhof von zentraler Be- Er soll deutung. Die Sanierung vorhan- attraktiver dener Gebäude und die schon werden. fertiggestellten neuen Bauten am Bahnhof schufen Raum für wei- tere Gesundheitseinrichtungen in Aschaffenburg. Hefner-AltenecK-Viertel Teilweise wurden vorhandene Praxen erneuert oder sie fanden neue, moderne Räume. Wei- tere Gesundheitsinstitutionen wIrD Zur Sozialen Stadt kamen hinzu. So ist rund um den Bahnhof – in der Ludwig- und Quartiersmanagement als Anlaufstelle für Bürgerinnen und Bürger Elisenstraße, in der Friedrich- straße, in der Goldbacher- und im mai hat der Aschaffenburger der Hefner-Alteneck-Straße errichtet, überdurchschnittlich hohen Anteil an Weißenburger Straße sowie in Stadtrat beschlossen, das Hefner- wie sie heute noch bestehen. Kindern und Jugendlichen. Deshalb der Heinse- und in der Frohsinn- Alteneck-Viertel zum Gebiet der So- Von besonderer Bedeutung für ist es besonders wichtig, maßnah- straße -

Africa and the OAU Zdenel< Cervenl<A

The Unfinished Quatfor Unity THE UMFIMISHED QUEST FORUMITY Africa and the OAU Zdenel< Cervenl<a JrFRIEDMANN Julian Friedmann Publishers Ltd 4 Perrins Lane, London NW3 1QY in association with The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies, Uppsala, Sweden. THE UNFINISHED QUEST FOR UNITY first published in 1977 Text © Zdenek Cervenka 1977 Typeset by T & R Filmsetters Ltd Printed in Great Britain by ISBN O 904014 28 2 Conditions of sale This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form or binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition inc1uding this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction by Raph Uwechue ix Author's Note xiv Map xx CHAPTER l:The Establishment of the Organization of African Unity 1 1. Africa before the OAU 1 2. The Addis Ababa Summit Conference 4 CHAPTER II: The OAU Charter 12 1. The purposes .12 2. The principles .13 3. Membership .16 CHAPTER III: The Principal Organs of the OAU. .. 20 1. The Assembly of Heads of State and Government .20 2. The Council of Ministers .24 3. The General Secretariat .27 4. The Specialized Commissions .36 5. The Defence Commission .38 CHAPTER lY: The OAU Liberation Committee . .45 1. Relations with the liberation movements .46 2. Organization and structure .50 3. Membership ..... .52 4. Reform limiting its powers .55 5. The Accra Declaration on the new liberation strategy .58 6. -

Female Combatants and Shifting Gender Perceptions During Zimbabwe’S Liberation War, 1966-79

International Journal of Gender and Women’s Studies March 2014, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 83-104 ISSN: 2333-6021 (Print), 2333-603X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development Female Combatants and Shifting Gender Perceptions during Zimbabwe’s Liberation War, 1966-79 Ireen Mudeka1 Abstract __________________________________________________________________ While mainstream history on the liberation struggle in Africa and Zimbabwe primarily focuses on male initiatives, from the 1990s, new scholarship marked a paradigm shift. Scholars both shifted attention to women’s roles and adopted a gendered perspective of the liberation struggle. The resultant literature primarily argued that the war of liberation did not bring any changes in either oppressive gender relations or women’s status. However, based on oral, autobiographical and archival sources including Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) documents and magazines, this paper argues that while male domination indeed continued, the war inevitably shifted perceptions of women. Their recruitment within ZANLA and in specific leadership roles marked this change in gender perceptions. Even ‘traditionally feminine roles’, normally taken for granted, gained new value in the cut-throat conditions of war. Nationalist leaders and other guerillas came to valorize such roles and the women who undertook them, as central to the war effort. War-time contingencies therefore spurred certain shifts in perceptions of women, at times radical but at others, seemingly imperceptible. This reevaluation of women’s status spilled into the postcolonial era, albeit slowly, due to the centuries-old patriarchal culture that Zimbabweans could not suddenly dismantle. __________________________________________________________________ Keywords: Zimbabwe, Liberation struggle, gender perception, women, history Introduction In his critical introduction to the theories of nationalism, U. -

2009–10 Annual Report (PDF)

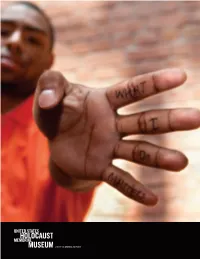

10 JUNE On June 10, 2009, our beloved colleague Special Police Officer Stephen Tyrone Johns died heroically while protecting the Museum and our visitors from a brutal attacker, an avowed antisemite and racist. Our Museum community is deeply grateful for the enormous outpouring of support worldwide, particularly the thousands who contributed so generously to the special fund to benefit the Johns family. USHMM.ORG 2009 –10 ANNUAL REPORT JUNE26 On June 26, 2010, WHDEARAT KINDFRIENDS, OF A dayW thatO wouldRLD reverberate throughout the nation started we launched the out like any other at the Museum. There were 42 scheduled groups that day—virtually all middle or high schools. Faculty from college campuses across this country were 10 WILL FUTURE GENERATIONS Stephen Tyrone Johns participating in our annual Silberman Seminar to strengthen teaching about the Summer Youth Leadership INHEHolocaust,RIT? taking their place in our worldwide network of scholars arming students with the truth. Historian Deborah Lipstadt, an expert on denial and a visiting fellow Program as a permanent, at our Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, had just begun speaking to Museum living tribute to Officer supporters when she heard shots. “I was about to say, ‘The dangers of Holocaust Johns. Every year, 50 denial are . ’ and that was it.” outstanding young people— That was it. In one horrifi c instant, a treasured colleague murdered. And our nation’s sacred memorial to the victims of unchecked hatred itself became a victim. JUNE On June 10, 2009, like the young man on THESE our cover—will learn our beloved colleague We don’t know exactly how people become haters and haters become killers. -

Timeline: History of South Africa and Denis Goldberg's Life History

Appendix 29. Timeline: History of South Africa and significant dates in Denis Goldberg’s life 1912: Foundation of the African National Congress (ANC). 1913: Lands Act bans the acquisition of land for Africans outside the reserves; eventually 13 per cent of the land area of South Africa. 1914 – 1918 First World War: black South Africans serve on European battlefields. 1921: Foundation of the South African Communist Party (SACP). 1923 – 1927: Apartheid laws: separation of residential areas according to race; restriction of the right to strike for Africans; ban on sexual relations between blacks and whites. 1933: 11 April: Denis Goldberg (DG) is born in Cape Town. Father and uncles work as small businessmen with trucks converted into buses. 1937: Ban on Jewish immigration through the Aliens Act against ‘non- integratable races’. 1939: September: declaration of war by South Africa on Nazi Germany, despite the great sympathy of many whites for the German fascists. DG starts school in Cape Town on his 6th birthday. 1944: Foundation of the ANC Youth League by Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Oliver Tambo, Lembede, Mda and others. 1948: The Afrikaner National Party comes to power in the ‘whites only’ election. Apartheid becomes the official doctrine of the state. 1949: DG last year at school; afterwards works on a fruit farm before university. 1950: ‘Racial classification’ of all South African after birth according to the ‘race’ of the father; final separation of settlements and residential 200 areas according to ‘races,’ mass forced resettlements; ban of the Communist Party. DG begins studies in civil engineering at the University of Cape Town. -

Interview with Ruth Weiss

Interview with PeaceWoman Ruth Weiss «Don’t look the other way when you witness any injustice» Ruth Weiss, one of the 1000 women nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, has dedicated her life to peace and tolerance – whether as a journalist and activist in apartheid South Africa or as a speaker and author fighting anti-Semitism «or any anti-any-religion sentiment». On the occasion of her 95th birthday in July 2019 we interviewed her about what lessons for peacebuilding she draws from her full life. As a child, Ruth Weiss fled Nazi oppression of the Jews in pre-war Germany and settled in South Africa. There she fought apartheid as a journalist and was declared a persona non-grata. In Harare, she co-founded the Zimbabwe Institute for Southern Africa that played an important role in paving the way for the end of apartheid. In 2005, she was nominated as one of 1000 women for the Nobel Peace Prize. PWAG: Before we begin, we would like to wish you a heartfelt “Happy birthday!” PeaceWomen Across the Globe wishes you all the very best on this special day. You have reached the formidable age of 95. Do you have any words of advice for anyone striving for such longevity? Ruth Weiss: Not really – except to say, not to be obsessed with one’s health. I’ve never “striven” for longevity, I am grateful for every day that I am permitted still to enjoy. And, I hate to say it, I never smoked or drank alcohol, but I know this is personal and not everyone’s choice. -

Whites in Zimbabwe and Rhodesia: Hapana Mutsauko Here

Southeastern Regional Seminar in African Studies (SERSAS) Fall Meeting 27-28 October 20 00 University of Tennessee, Kn oxville Tennessee, USA Whites in Zimbabwe and Rhodesia: Hapana Mutsauko Here. Is it the same difference? David Leaver Raymond Walters C ollege University of Cincinnati Quote with Permission from [email protected] Copyright © 2001 by David Leaver All Rights Reserved There is no intention on our part to use our majority to victimize the minority. We will ensure there is a place for everyone in this country. We want to ensure a sense of security for both winners and losers. (Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe's new Prime Minister, election night 1980) If the new millennium, like the last . remains the age of the master race, of the master economy and the master state, then I am afraid we in developing countries will have to stand up and say: "Not again". (Robert Mugabe, July 2000 Millennium summit).[1] In an effort to incite popular support once enjoyed after Zimbabwe's liberation struggle (1962-1980), President Robert Mugabe, as victor over white supremacy, today denounces his country's tiny white minority for racial privilege and supposed alien loyalties.[2] Until the mid-1990s, while he pursued national reconciliation after bloody civil war, Mugabe enjoyed respect abroad and popular support at home. Then at the polls his Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) was twice rejected, especially by urban 'born frees', younger voters lacking experience of the liberation struggle. Rejection came as a 'no' vote in a February 2000 constitutional referendum to approve uncompensated confiscation of white commercial farms. -

Afrikander Volunteer Corps and the Participation of Afrikaners in Conflicts in Rhodesia, 1893–1897

25 THE AFRIKANDER VOLUNTEER CORPS AND THE PARTICIPATION OF AFRIKANERS IN CONFLICTS IN RHODESIA, 1893–1897 Gustav Hendrich Department of History, Stellenbosch University Abstract During the last decade of the nineteenth century, British colonisation in Southern Africa, in particular in Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe) had coincided with uneasy relations with the native black population. Partly because of continuing disillusionment over stringent policy regarding native livestock, hostilities between the colonial officials and Matabele and Mashona tribal groups resulted in devastating wars. Within these warring circumstances, Afrikaner settlers who had immigrated to Rhodesia since 1891 – mostly in search of better living opportunities – subsequently found themselves amidst the crossfire of these conflicts. Though subjugated to British colonial authority, the Afrikaner minority were regarded by native blacks as collaborators in maintaining white military and political power in Rhodesia. Consequently, the mere safety of Afrikaners were threatened by sporadic military attacks and skirmishes during the Anglo-Matabele war of 1893, and most of all, for the duration of the Matabele and Mashona rebellions of 1896 to 1897. During the Matabele rebellion, an Afrikander Volunteer Corps (known as the Afrikaner Korps) was established as a military unit, which provided substantial support in two decisive battles. This article seeks to address the role and history of the Afrikander Volunteer Corps, as well as the involvement of ordinary Afrikaners in the turbulent colonial wars in early Rhodesia. Introduction Unfavourable states of war occurred more or less simultaneously with the arrival in Rhodesia of the first Afrikaner treks. Increasing enmity between the British colonialists and the traditional Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, indigenous population groups, the Matabele Vol 40, Nr 1, 2012, pp.